‘Pointillist’ colonialism treats millions of U.S. citizens as foreigners

[divider_flat]

[divider_flat]

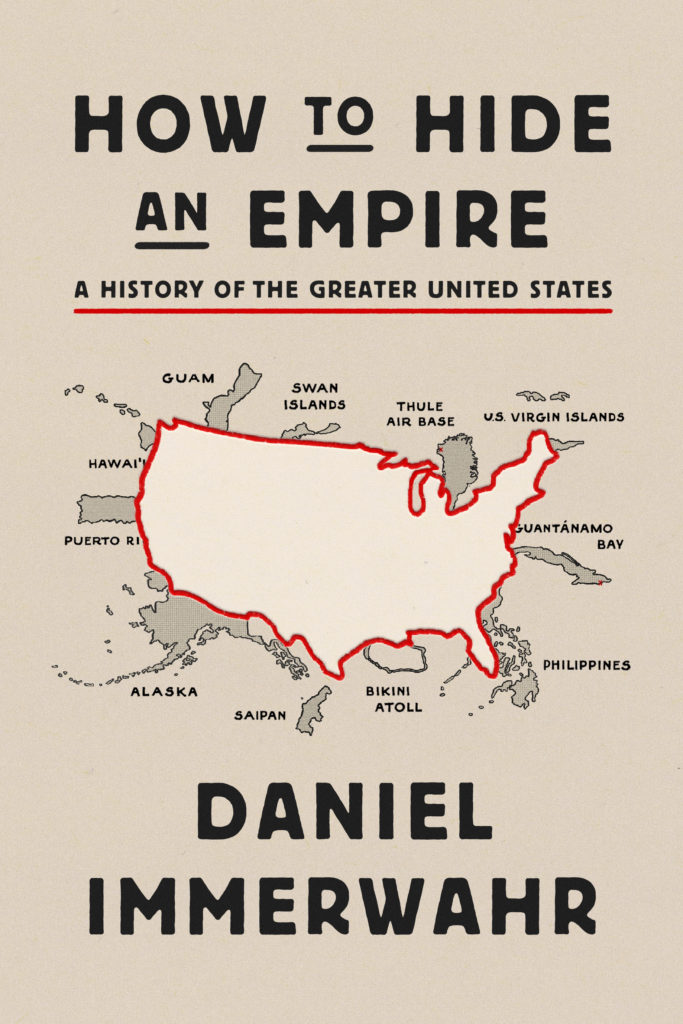

Daniel Immerwahr, associate professor of history at Northwestern University, is author of How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2019). His first book, Thinking Small: The United States and the Lure of Community Development, won the Organization of American Historians’ Merle Curti Award.

[divider_flat]

By Daniel Immerwahr

Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2019, $30

You assert that the United States has a long unacknowledged history of empire. Often, when we talk about “American empire,” we talk about imperialism, from Manifest Destiny to military interventions in the Middle East. When I say the history of the United States is one of empire, I’m referring not to imperialism but to territory, not to the character of the country but to its shape. Ever since gaining independence from Britain, the United States has contained not only states but territories. These aren’t small; by 1940, one person in eight living in the United States resided in the territories, and the country contained more colonial subjects than African Americans or immigrants. Yet the territories, particularly those overseas, haven’t always been easy for historians studying the United States to see.

What accounts for this lack of awareness?

I grew up on the American mainland, and at no point in my education do I remember even seeing a map of the United States that had Puerto Rico on it, though Puerto Rico has been part of the United States for 120 years. The same is true of the census, whose statistical calculations—how long people live, how many people live in cities, and so forth—largely have included only the mainland and states, not overseas territories. The larger issue is surely this: There has been a longstanding, racially informed sense on the mainland that certain parts of the United States “count” while other parts don’t, that certain parts of the country are truly “America,” whereas others are merely possessions.

Seventh graders at Western Michigan Training School caught onto this in 1941. After Pearl Harbor, President Franklin Roosevelt enjoined Americans to follow the war on maps. Seventh-grade girls in Kalamazoo tried that, using a Rand McNally war atlas. The atlas listed Hawai‘i as a foreign country, along with Puerto Rico and Alaska. Wondering how an attack on “foreign” Hawai‘i could have led the United States into war, the students asked Rand McNally what kept Hawai‘i from being part of America. The publisher replied that because Hawai‘i is “foreign to our continental shores,” it couldn’t be shown as part of the United States. This small example shows the persistence of the assumption that some parts of the United States are really part of the country, while others aren’t.

How did the United States justify annexing the Philippines after the Spanish-American war? President William McKinley said the United States had an obligation to civilize the Filipinos. More broadly, the Philippines annexation was part of a forthright turn by America’s leadership away from what had been the prevailing pattern among imperial nations of settler colonialism and toward the ruling of large, distant populations. We don’t normally think of the United States as a colonial power in that sense, but by the 1920s the country had the world’s fifth-largest empire by population—some 19 million colonial subjects.

Many white Americans in the Lower 48 weren’t keen to acquire Alaska, Hawai‘i, and other territories home to nonwhites. Racism comes in flavors. There’s the racism that proposes that whites rule nonwhites. Another kind insists that white people have as little to do with nonwhites as possible. In the United States of the 19th century, you can see these variations fighting with each other. Much resistance to colonial empire comes not from sympathy with the colonized but from the desire to preserve the whiteness of the United States.

After 1945, America did something very unusual. The historical pattern had been: When you get more power, you get more territory. At the end of World War II, the United States ruled a larger population in colonies and occupied territories than on the mainland. But instead of going on an imperial spree, the country sought to distance itself from the colonial model by ending its occupations, letting go of its largest colony, the Philippines, and making states of Hawai‘i and Alaska. Instead of becoming a world-girdling colonial empire, the United States became what I call a “pointillist empire.” The United States continues to hold colonies—millions live in them today—but its main interest seems to be small enclaves, such as hundreds of foreign military bases, that dot the globe.

How did science influence America’s shift to decolonization? Historically, great powers have sought large colonies for access to strategic resources. In the industrial world, that has meant rubber, palm oil, tin, gutta-percha, and the like. But now colonization is not the only way to get those resources. You can get them through chemistry. In the 1940s, to a remarkable extent, the United States developed substitutes for key raw materials. When Japan cut off America’s supply of natural rubber, American scientists learned to

synthesize rubber from petroleum, substitute nylon for hemp and silk, and swap chloroquine for quinine. After the war, able to substitute technology for territory, the United States didn’t need large colonies as much.

Describe America’s attitude toward its overseas charges. In 1913, Woodrow Wilson described those territories as “outside the charmed circle of our own national life.” People in the territories can’t vote for president. They have no meaningful representation in Congress. The Constitution doesn’t apply to them. Exclusion from all three branches of government has had serious consequences. In wartime, territories have tended to be sacrifice zones—in my book, I tell how during World War II the Philippines became a bloodlands. In peacetime, doctors, lawyers, and other experts have been drawn to the territories as laboratories, where ideas can be tested with relatively little oversight.

America’s empire endures. How? That empire endures in American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Marianas, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands and their 3 to 4 million inhabitants, and in foreign military bases; a recent count put them at 800. The consequences of empire are palpable. In the 1940s, Rand McNally doubted whether Hawai‘i was truly “American.” More recently, Barack Obama, whose father was from Kenya and who was born and raised in Hawai‘i and elsewhere in the Pacific, was the target of rumors about whether he was “American.” If you look at the origins of birtherism—Donald Trump’s entry ticket into presidential politics—it’s clear that it was triggered by Obama’s Pacific birth and upbringing, not just his being black.