Any discussion of World War I air combat usually brings to mind the image of nimble single-seat fighters engaged in dogfights above the trenches, aircraft such as the S.E.5, Sopwith Camel, Nieuport and Spad. At the time, however, the single-engine, single-seat aircraft was not yet universally acknowledged as the optimum air combat weapon. One of the most formidable fighter planes of the period was a single-engine two-seater, the Bristol F.2B, which was generally known as the Bristol Fighter, as well as the “Brisfit” or “Biff.”

Often overlooked by modern historians assessing the merits of World War I aircraft, the F.2B was regarded as a great success in its day. It was among the few aircraft to remain in production after hostilities ended, and on active military service long after the conflict. The Royal Air Force (RAF) did not retire the last of its F.2Bs until 1931, and many Bristol Fighters served in other air arms, including the U.S. Army Air Service.

The Bristol Fighter originated from a 1916 design proposal for a new reconnaissance plane to replace the Royal Aircraft Factory’s B.E.2, a two-seat biplane of prewar design. The B.E.2 served in many roles during the first two years of the conflict, including reconnaissance, artillery spotting, light bombing and even intercepting German Zeppelins. Although the B.E.2 was originally selected for service because it was stable and easy to fly, operational experience revealed that those same qualities rendered the aircraft vulnerable to attack by specialized fighter planes, starting with the revolutionary Fokker monoplane, the first tractor-engine, single-seat fighter armed with a machine gun synchronized to fire forward through the propeller. Late in 1915, the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) issued a requirement for a B.E.2 replacement capable of defending itself against air attack. It needed to be faster and more maneuverable than the old B.E.2, and both the pilot and observer were to be armed with machine guns.

A number of British companies submitted proposals to meet the reconnaissance plane requirement. The one that was eventually accepted for production was the Royal Aircraft Factory’s own R.E.8, a sturdy but rather conventional design. Among the rejects was the R.2A, submitted by the British and Colonial Aeroplane Company.

British and Colonial had been established in 1910 at Filton, a suburb of Bristol, by Sir George White, a self-made Bristol businessman and philanthropist. At age 56, he was a good deal older than most aviation pioneers, and he was neither an aircraft designer nor a pilot. He firmly believed in the future of aviation, however, and he possessed both the organizational experience and the financial capital to ensure his company’s success. White had introduced the first production airplane to Britain, the Bristol Boxkite, and sold the first aircraft to the British army.

White also established airfields and training facilities to make flying viable for the public as well as the military. He sent delegations abroad to India and Australia to demonstrate aviation’s potential and was the first British manufacturer to sell airplanes for export. Proud of his home city, White eventually changed his firm’s name to the Bristol Aeroplane Company.

The designer of the R.2A was Captain Frank Barnwell, who joined Bristol in 1911 as the company’s chief draftsman and became its chief designer in 1915. He had previously designed the Bristol Scout, which was originally built as a racer. A handsome little single-seat biplane with an 80-hp rotary engine, the Scout was produced in large numbers during the first year and a half of the war. Like most prewar airplanes, however, the Bristol Scout had not been designed to carry a machine gun, and attempts to transform it into an armed fighter were never altogether successful. Barnwell’s next fighter design was an advanced shoulder-wing monoplane called the Bristol M-1, which performed very well but was eventually rejected due to the RFC’s prejudice against monoplane designs.

Designed for a 120-hp Beardmore engine, Barnwell’s R.2A was not expected to perform sufficiently better than the B.E.2 to merit further development. That expectation changed, however, when the Air Ministry offered Bristol a new engine for the project in the spring of 1916—the 190-hp liquid-cooled Rolls-Royce Falcon. The installation of that engine transformed Barnwell’s two-seater from potential prey into lethal predator and established a whole new aircraft category, the fighter-reconnaissance plane. That change in emphasis was reflected in the revision of the aircraft’s designation from R.2A to F.2A.

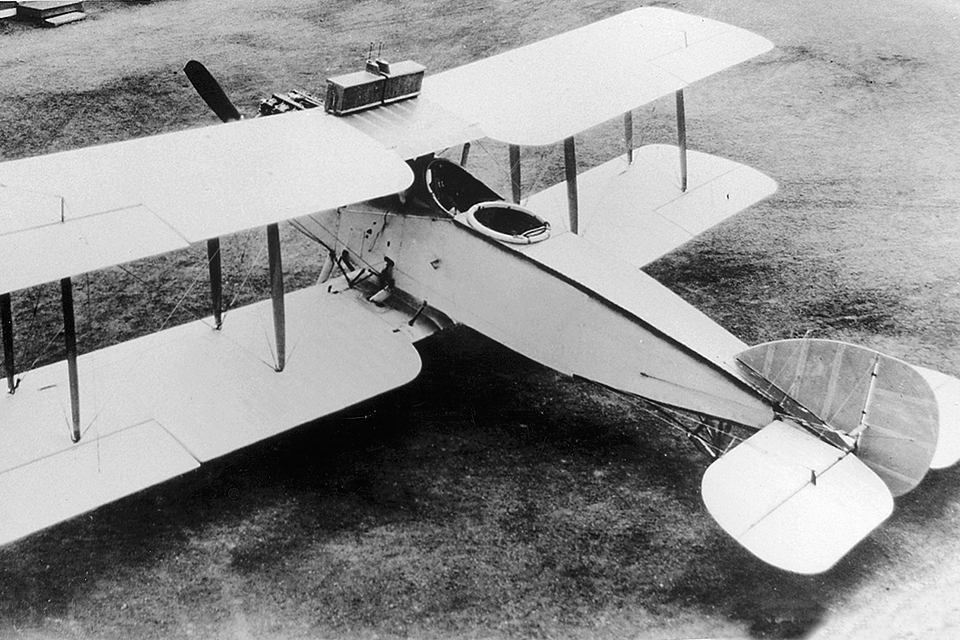

Bristol constructed two prototype F.2As during the summer of 1916, one with a 190-hp Falcon and the other with a 200-hp liquid-cooled Hispano-Suiza V-8 engine. The Rolls-Royce–powered first prototype, which initially flew on September 9, was equipped with clumsy side-mounted radiators. They were soon replaced with a circular radiator in the nose that reduced drag and improved the pilot’s vision.

Like the projected R.2A, the F.2A was a single-engine, two-seat biplane. Each of the equal-span, two-bay wings was fitted with ailerons, endowing the plane with outstanding maneuverability. In contrast to conventional biplane designs, the Bristol’s fuselage was supported on struts at the mid-gap position between the wings. That arrangement lowered the upper wing to a position closer to the fuselage, providing the pilot with an excellent view both above and below it. In an era when seeing the enemy first often made the difference between life and death, pilots appreciated the superior view from the Bristol Fighter’s cockpit. The fuselage’s mid-gap position also gave Barnwell’s design an air of fragility, accentuated by the way the landing gear legs projected through the open lower wing center section. Looks can be misleading, however, for the Bristol could withstand violent combat maneuvers as well as any single-seat fighter of the era.

The F.2A was armed with a single synchronized forward-firing .303-inch Vickers machine gun mounted inside the forward fuselage, between the engine’s cylinder banks. The breach was accessible to the pilot so that he could clear jams, a common occurrence. The gun discharged through a blast tube and out through a hole in the top of the radiator. Some home-defense Bristol Fighters carried one or two additional forward-firing Lewis guns mounted over the upper wing.

The observer had a .303-inch Lewis gun on a Scarff ring mounting. Later in the war the rear cockpits of some Bristol Fighters were equipped with twin Lewis guns. The observer could rotate the Scarff ring through 360 degrees and, if necessary, elevate the machine guns to a position from which he could fire forward over the top wing almost horizontally. To further improve the gunner’s field of fire, the rear fuselage tapered sharply downward into a horizontal knife-edge, and part of the low-aspect-ratio vertical stabilizer was set below the fuselage.

Many bombers and reconnaissance planes of the period mounted armament similar to that of the Bristol Fighter. However, one indication of the more offensive role planned for the F.2A was the larger amount of ammunition it was designed to carry. The front gun’s ammunition box held 963 rounds, and the rear cockpit contained racks for seven 97-round drums.

In addition to the machine guns, the Bristol Fighter could be equipped with cameras for reconnaissance missions or wireless equipment for artillery spotting. On bombing missions it could carry up to a dozen 25-pound bombs or a pair of 112-pound bombs. A bombsight could be installed that sighted through a special fairing which extended below the fuselage and through the lower wing center section.

Although the first production Bristol F.2As were issued to No. 48 Squadron in December 1916, they were with- held from combat until the British spring offensive, when the general staff hoped to surprise the German air service with their formidable new two-seat fighters. The F.2A’s combat debut was far from auspicious, however. When six of No. 48 Squadron’s planes crossed the lines for the first time on April 5, 1917, German fighters shot four of them down without any losses on their own side.

Part of the reason for that disastrous outcome was the fact that the inexperienced British crews had the misfortune to encounter the legendary Manfred Freiherr von Richthofen and four members of his Jagdstaffel (or Jasta) 11, arguably the most skillful fighter pilots in the world at that time. Equally to blame, however, were the flawed tactics employed by No. 48 Squadron. Under the mistaken impression that their new planes were structurally weak, the British made the fatal mistake of closing up into tight formation and relying upon the rear cockpit gun as the principal armament. Once British pilots began flying the Bristol Fighter in the same offensive manner as a single-seat fighter, utilizing the front gun as the main weapon and relying on the rear gunner to cover the tail, they quickly turned the tables on their opponents. The Bristol Fighter eventually acquired such a fearsome reputation that enemy fighter pilots became reluctant to attack formations of more than two of the British two-seaters at a time.

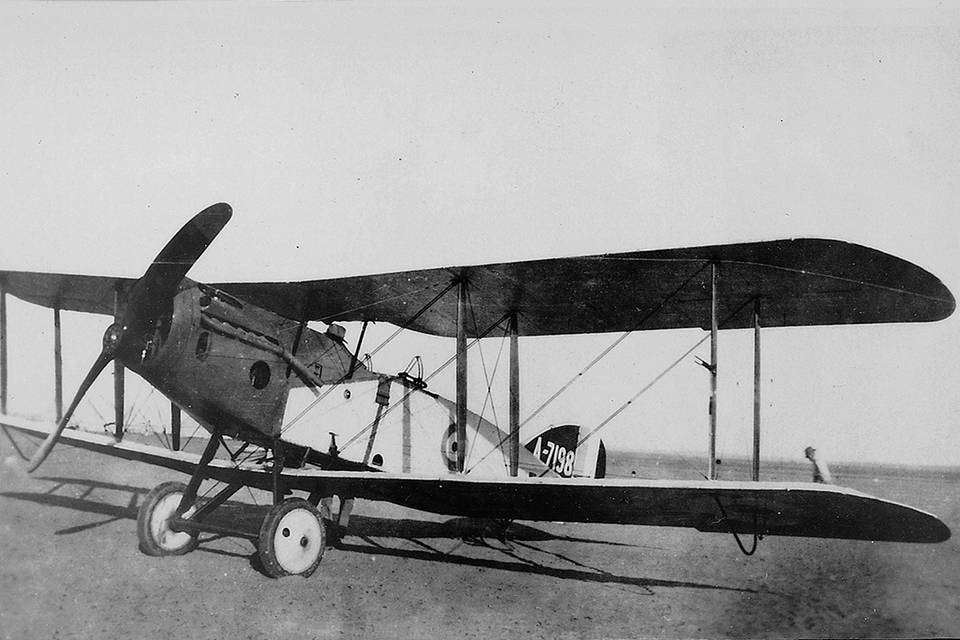

Only about 150 F.2As were built before they were superceded by the definitive version, the F.2B. The F.2B was equipped with the 220-hp Falcon II engine and later the even more powerful 275-hp Falcon III. Other changes included a redesigned elevator and tailplane. The most noticeable alteration, however, resulted from the downward angle built into the upper fuselage longerons forward of the cockpit. That lowered the cockpit coaming and narrowed the top of the engine cowling, which further enhanced the pilot’s view forward and downward. Along with that design change came a new oval-shaped radiator with controllable shutters.

The Falcon III–powered Bristol Fighter was 25 feet 10 inches long and had a wingspan of 39 feet 3 inches. The plane weighed 1,934 pounds empty and 2,779 pounds fully loaded. The F.2B had a top speed of 113 mph at 10,000 feet, which was equal to or better than the majority of single-seat fighters of the period. It could climb to that altitude in just over 11 minutes. The service ceiling was 20,000 feet, though operation at that altitude for extended periods would have been hazardous, since the aircraft were not supplied with oxygen equipment. Fully loaded, the plane had an endurance of three hours.

One of the F.2B’s best features was its smooth-running, reliable Rolls-Royce Falcon engine, the product of a firm that had already established a reputation for quality. The British experienced only one major problem with the Falcon engines: They couldn’t get enough of them. As a result, the Air Ministry attempted to substitute a variety of other manufacturers’ engines in the Bristol Fighter, most of which proved unsuitable. In the end, the only viable alternative to the Falcon was France’s 300-hp Hispano-Suiza, a liquid-cooled V-8. That engine only became available after the war, and by that time the RAF had lost interest in using foreign-built engines. Hispano-powered F.2Bs did serve in several postwar air forces, however, including those of the United States, Poland, Belgium and Spain.

F.2B pilots described it as very easy and comfortable to fly. It also proved to be very maneuverable for a two-seater. Also noteworthy was the fact that the Bristol’s pilot could easily adjust the tailplane incidence while in flight, enabling him to fly or glide at any speed without effort.

One of the Bristol’s principal tactical advantages lay in its crew layout. Many Allied two-seaters, such as the Sopwith 11⁄2-Strutter, de Havilland D.H.4 and Salmson 2A2, had widely separated cockpits. In an era before the advent of intercommunication, that made it difficult for the crew to cooperate in combat. On the Bristol, in contrast, the close proximity of the cockpits enabled the pilot and observer to work together very effectively as a team.

The Bristol Fighter was one of the few two-seaters of World War I to produce a significant number of ace fighter pilots— and for that matter ace observers. Outstanding among those crews was the F.2B team of Canadian Captain Alfred Clayburn Atkey and his observer, British Lieutenant Charles George Gass of No. 22 Squadron, who together shot down 29 enemy aircraft in less than a month, from May 7 to June 2, 1917. Only a few fighter pilots have ever managed to shoot down five enemy planes in one day; Atkey and Gass were credited with accomplishing that feat twice, on May 7 and May 9, 1917. On one occasion, when part of their upper wing was shot away, Gass climbed out onto the lower wing to balance the damaged plane so that Atkey could safely land it.

Thirteen of the team’s victories were actually credited to Gass. Probably the most successful rear gunner in history, Gass participated in 39 aerial victories while flying with various pilots, 17 of which were credited to him alone. Gass, who began his military career as an infantry private, rejoined the RAF during World War II and eventually became a squadron leader.

Captain Ross Macpherson Smith and his observer, Lieutenant A.V. McCann of No. 1 Squadron, Royal Australian Flying Corps, provided another example of how aggressive Bristol Fighter crews could be. After they forced an enemy two-seater to land behind Turkish lines on October 19, 1918, Smith landed next to the damaged aircraft and set it on fire while McCann covered its crew with his machine guns. After scoring eight victories in the Middle East, Ross Smith and his brother Keith accomplished the first flight from England to Australia in 1919, taking off from Hounslow in a Vickers Vimy bomber on November 12 and arriving in Darwin on December 10.

Number 20 Squadron had the rare distinction of including two American brothers on its roster of F.2B pilots, both of whom became aces. The two New Yorkers, August and Paul Iaccaci, joined the RFC in Canada. Both survived the war, and each was credited with 17 victories.

Another unusual incident involving the Bristol Fighter occurred when Edward, Prince of Wales—the future King Edward VIII and Duke of Windsor—flew over Austrian lines on September 16, 1918. A staff officer on the Italian front, Edward was visiting No. 139 Squadron when he took off with the squadron commander, Canadian Major William G. Barker. Edward’s aides, who believed the prince was only undertaking a brief hop around the field, were horrified when the F.2B disappeared over the front for a considerable period of time. When they returned, neither Barker nor the prince ever admitted that they had actually flown over the enemy lines, but it seems likely that is what occurred. That Barker should have attempted such a thing indicates not only the confidence he had in his own ability but also in the flying qualities of the F.2B.

The most famous of all the Brisfit teams was Canadian Lieutenant Andrew Edward McKeever and his Bristol-born observer, Lieutenant Leslie Archibald Powell, of No. 11 Squadron RFC. McKeever’s exceptional total of 31 victories, gained between June and November 1917, was entirely achieved in Bristol Fighters. On November 30, 1917, McKeever and Powell engaged two German two-seaters and seven single-seat fighters, and were credited with shooting down four of the enemy—three of them within 30 seconds. Both men survived the war, Powell finishing up with 19 victories. McKeever formed and commanded No. 1 Squadron, Royal Canadian Air Force, and ended the war with the rank of lieutenant colonel. He became the airport manager at Mineola Field on Long Island, N.Y., where he died in 1919 as a result of a car accident.

Bristol Fighters eventually equipped 13 squadrons on the Western Front. Others saw service in Italy and the Middle East. F.2Bs also equipped five Home Defense squadrons as night fighters, in which role they successfully intercepted several Gotha bombers. In addition to aerial combat, they were used for artillery spotting, reconnaissance, liaison, close air support, trench strafing and light bombing. A total of 4,747 Bristol Fighters were produced through September 1919, 10 months after the armistice.

After the United States entered the war on April 6, 1917, the F.2B was among the handful of foreign aircraft designs selected to equip the American Expeditionary Force at the recommendation of its commander, General John J. Pershing. The manufacturing license did not include the Rolls-Royce engine, however. The U.S. Army wanted the Bristol Fighter modified to accept either the American-designed Liberty engine or license-built Hispano-Suiza engines. As a result of much extensive and unnecessary redesigning, the first American-built F.2B, designated the O-1, did not fly until March 5, 1918. Glenn H. Curtiss contracted to build 2,000 of the aircraft under license, but it was not a success. The bulky Liberty engine was unsuitable for the Bristol Fighter, spoiling its good handling qualities and overstressing the airframe. Three of the new O-1s soon crashed, and two of those mishaps were blamed on faulty workmanship. Quality control was considered so shoddy that the U.S. production program was canceled after only 27 O-1s were completed.

Later in 1918 the Dayton-Wright Company produced a modified version, the B-1A. Powered by a 330-hp Wright engine, the B-1A had a new fuselage of wood-veneer monocoque construction. Dayton-Wright eventually produced 40 B-1As, which were intended to carry out nocturnal observation missions. None of the American-built Bristol Fighters ever got to France, but Major Rudolph W. Schroeder of the U.S. Army Air Service flew one to an unofficial altitude record of 29,000 feet over Dayton, Ohio, on November 18, 1918.

Though the Bristol Fighter as modified was a failure in the United States, the British found a ready market for their sur- plus F.2Bs among other foreign governments after the armistice. A hundred were sold to the new Polish air force, which equipped three reconnaissance squadrons with F.2Bs. Belgium operated 71 Bristol Fighters, of which 40 were produced locally under license. Other air forces that bought F.2Bs included those of Spain, Mexico, Ireland, Norway, Greece, Canada, New Zealand and the air arm of Chinese Republic President Sun Yat-sen.

The RAF, however, did not liquidate all of its surplus Bristol fighters. Of 3,830 aircraft in RAF service in December 1921, 1,090 were F.2Bs, making them the most numerous British military aircraft of the immediate postwar period. Though no longer considered a formidable air-to-air combatant, the versatile Bristol was still a valuable reconnaissance, close support and army cooperation machine.

That was particularly the case when the RAF assumed responsibility for policing the Middle East and the Indian Northwest Frontier in 1922. Loaded with spare parts and desert survival equipment, F.2Bs patrolled some of the most forbidding terrain in the British empire. For army cooperation duties in the Middle East, Bristol rebuilt 415 aircraft into F.2B Mk. IIs. The conversion included a more efficient cooling system to deal with desert conditions, racks for up to a dozen 20-pound bombs and a reinforced landing gear for operation outside of unimproved airfields. Another addition to the F.2B Mk. II was a long hook attached to the bottom of the fuselage. In an era when neither ground forces nor aircraft were routinely supplied with radio equipment, troops were able to communicate with aircraft by suspending written messages on a line strung between two poles, which the Bristol could snatch up with its hook.

The British Air Ministry sponsored competitions among the leading aircraft manufacturers to produce a replacement for the Bristol Fighter in 1922 and 1926, but none of the competing designs was accepted. Part of the reason was the postwar government’s reluctance to spend money on military appropriations. In addition, however, none of the new aircraft demonstrated a significant improvement over the F.2B. To extend their usefulness, in 1926 many of the surviving Bristols were rebuilt to Mk. III standards, with a strengthened structure that could carry heavier loads.

The final version, the F.2B Mk. IV, included aerodynamic refinements such as a larger rudder and leading edge slats on the upper wings. Fifty of them were converted in 1928 from earlier versions. By then, however, it was becoming clear that the Bristol Fighter’s operational days were numbered. Apart from everything else, the tropical conditions under which many of them served took a severe toll on the plane’s wooden structure. It had become obvious to the RAF that the future belonged to all-metal aircraft—such as the highly successful Hawker Hart, introduced in 1928. Some of the surviving Bristol Fighter Mk. IVs were modified into two-seat trainers, serving with the Oxford and Cambridge University Training Squadrons until 1931.

The operational success of the Bristol Fighter exerted great influence over combat aircraft design throughout the world for two decades after the plane’s introduction. Two-seat combat planes such as the Hawker Hart, the light bomber that replaced the Bristol, were expected to perform with equal efficiency as fighters. The RAF operated a two-seat fighter version of the Hart called the Hawker Demon until 1938. The two-seat fighter persisted throughout the world until the concept was ultimately discredited during the Battle of Britain in 1940. Still, the recent success of high-performance fighters carrying an extra crewman to man the radar, missiles and other electronics while the pilot concentrates on flying the plane, such as the McDonnell F-4 Phantom and F-15 Eagle and the Grumman F-14 Tomcat, suggests that the two-seat fighter concept may have life in it yet.

The F.2B was the last airplane produced by Bristol under the management of the company’s founder, Sir George White, who died in 1916. Under the leadership of his son Samuel, however, the company developed into one of the giants of the British aviation industry. During the 1920s Bristol expanded into aero-engine development so it would never again have to depend upon other manufacturers for a sufficient supply of engines.

Frank Barnwell remained chief engineer at Bristol until his death in 1938. His designs included the highly successful Bulldog single-seat biplane fighter of 1927 and his last, a twin-engine light bomber 50 mph faster than the fighters then in RAF service. Called the Blenheim, it was produced in large numbers during World War II and served as the basis for other successful warplanes such as the Beaufort torpedo-bomber and Beaufighter multirole aircraft.

After World War II, Bristol diversified into new fields, including helicopter development and automobile production. In 1960 the British government forced the aviation side of the company into a merger with the British Aerospace Corporation. The aero-engine division merged with Armstrong-Siddeley at the same time. A supersonic fighter prototype, the Bristol 221, was the last aircraft to bear the company’s name. The automobile division, however, still remains in business under the control of the Sir George White’s descendants. It continues to manufacture a high-performance two-seat sports car called, appropriately enough, the Bristol Fighter.

F.2Bs can be seen on static display at the Imperial War Museum in Duxford and the RAF Museum in Hendon. In addition, the Belgian Air and Military Museum in Brussels has a Hispano-Suiza–powered Bristol Fighter. Aircraft home-builder Ed Storo of Memphis, Tenn., took seven years to build an exact replica F.2B, which he later sold to movie director Peter Jackson, director of the Lord of the Rings trilogy, who flies it in New Zealand.

The most authentic F.2B is the one belonging to the Shuttleworth Collection at Old Warden in Bedfordshire, England. The history of Shuttleworth’s Bristol has been researched and authenticated back to its construction in 1918 and service with the RAF. Discovered in storage in 1949, the aircraft was meticulously restored by Bristol to its original condition and appearance. It is one of the very few original World War I aircraft still maintained in flyable condition.

Merchant Marine officer Robert Guttman suggests for further reading: Bristol Aircraft Since 1910, by C.H. Barnes; and Bristol Fighter in Action, by Peter Cooksley.

Originally published in the January 2006 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.

Ready to build your own Bristol F.2b to add to your collection? Click here!