On July 26, 1944, Technician Fourth Grade Hoichi “Bob” Kubo stepped from the jungle on the northern tip of Saipan and strode toward eight Japanese riflemen guarding the mouth of a cave that held more than 100 civilians—men, women and children. The battle for the largest of the Northern Mariana Islands was over, but the solo action that would earn Kubo the highest honor of any Japanese-American soldier in the Pacific had just begun.

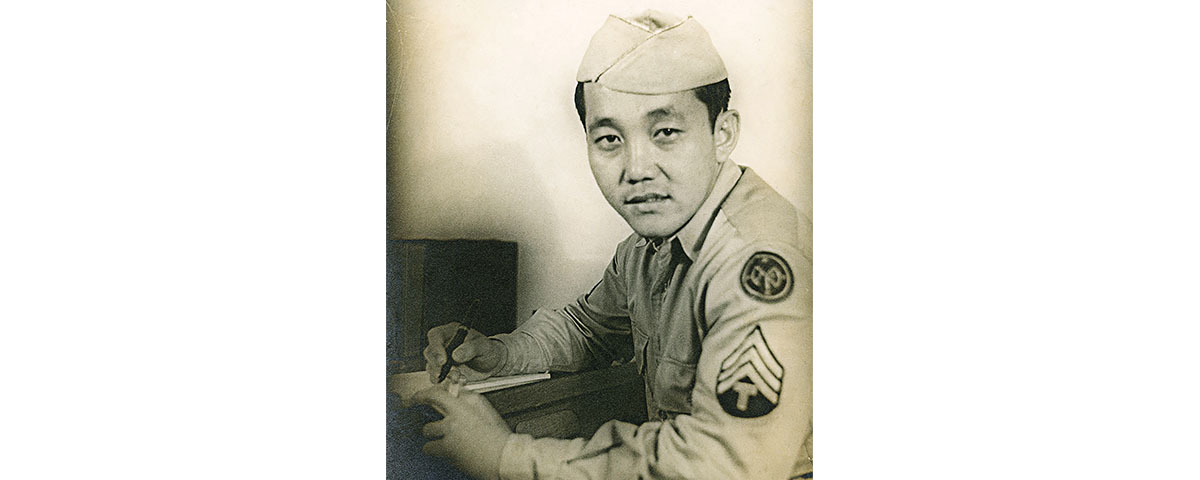

Born on Maui in 1919 to first-generation Japanese immigrants (Issei), Kubo was studying agriculture at the University of Hawaii when drafted in June 1941. Six months later he watched from Oahu’s Schofield Barracks as Japanese planes strafed the island, triggering the Army to group Kubo and other Nisei soldiers in Hawaii into the 100th Infantry Battalion and ship them to Camp McCoy, Wis.

In June 1942 Military Intelligence Service recruiters came seeking Japanese linguists. Kubo was chosen one of more than 6,000 Japanese-Americans who supported U.S. and Allied uniformed services as translators and interrogators.

In the summer of 1944 Kubo was attached to the 27th Infantry Division, interpreting captured documents and questioning prisoners on Saipan. After U.S. forces secured the island on July 9, thousands of surviving enemy soldiers either committed suicide or retreated into Saipan’s cavern-laced interior. Kubo was among several Japanese-American cave flushers tasked with coaxing surrenders from the holdouts. On the morning of July 26 he was on patrol with an infantry platoon when a pair of civilians reported they had escaped from a cave at the base of a nearby cliff where Japanese soldiers had been holding more than 100 hostages for 10 days. Kubo volunteered to lobby for the captives’ release.

Armed with only a .45-caliber pistol, his pockets full of K rations, Kubo rappelled more than 100 feet down the cliffside and searched for the cave.

The enemy soldiers branded Kubo a spy until he identified himself as an American negotiator. Curious why he wore a U.S. uniform, the soldiers invited Kubo to sit with them around a pot of rice. Kubo spoke of his grandfathers, who had served in the Japanese army during the 1904–05 Russo-Japanese War. When asked why he fought against Japan, the Nisei quoted a 12th-century Japanese proverb, “If I am filial, I cannot serve the emperor. If I serve the emperor, I cannot be filial.” The soldiers understood his allegiance was to the land of his birth.

For nearly two hours Kubo spoke with the soldiers, gaining their trust as he urged them to not disgrace Japan by killing noncombatants after battle had ceased. Kubo then scaled the rope back to his anxious platoon. At 2 p.m. the first of the 122 hostages crawled over the ledge, eventually followed by the eight surrendering Japanese.

In January 1945 Kubo received the Distinguished Service Cross, the Army’s second highest valor award. “Kubo’s heroism,” noted his citation, “prevented casualties among our troops and undoubtedly saved the lives of the civilians, who would have perished had it been necessary to dynamite the cave.”

Kubo went to Okinawa, where he watched the Japanese surrender party board an American aircraft for Manila. After the war he became a successful grocer in San Jose, Calif., where he died in 1998. His heroic action is captured in Cave Flushing, a sculpture in the National Museum of American History exhibit “A More Perfect Union,” which explores the Japanese-American experience in World War II.