SOON AFTER THE FIRST GUNS roared at Fort Sumter, Union brigadier general Samuel P. Heintzelman lamented that there were two spies behind every window curtain in Washington. Heintzelman may have been a bit paranoid, but as Henry Kissinger and others have said, even paranoids can have real enemies. Hundreds of Confederate sympathizers held sensitive jobs in the Federal government. Three-quarters of the capital’s residents were either born in the slave states of Maryland and Virginia or had roots there.

Conrad said he “would have crept into a cannon and been fired into fragments” to defeat the Union

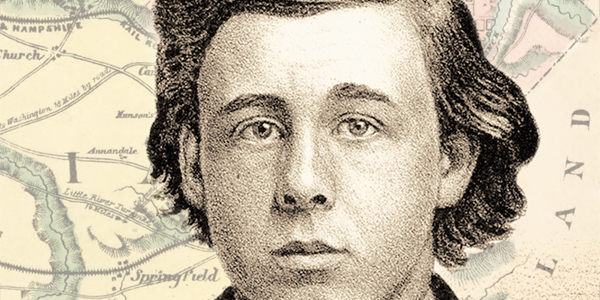

No Washington neighborhood was more closely tied to the South than Georgetown, then a town within the District of Columbia. The 1860 census found that only 142 of its 8,766 residents hailed from north of the Mason-Dixon Line. And no one in Georgetown was more defiantly pro-Confederate than Thomas Nelson Conrad, a 23-year-old Methodist lay preacher and headmaster of the Georgetown Institute, a boys’ preparatory school.

Apparently protected by his clerical role, Conrad, known as “the Reverend,” preached and plotted sedition for months after Sumter. Deep into 1862, Conrad was still teaching the Rebel gospel and plotting the assassination of a Union general. He would go on to become one of the South’s most daring agents, building a busy Confederate intelligence channel and even cooking up a scheme to kidnap Abraham Lincoln.

Born outside Washington in Fairfax, Virginia, Conrad had done his religious studies at Dickinson College in Pennsylvania before moving to Georgetown and founding the boys’ school. When war began, he advised his students how to join the Rebel army. Some said he signaled Confederates across the Potomac River by raising and lowering window shades at the school.

In his memoirs—the best account of his work, albeit written 30 years after the war and undoubtedly colored in Conrad’s favor—the preacher recalled dreaming up a plan to shoot Union general in chief Winfield Scott, a fellow Virginian whom he condemned as a traitor. But Confederate officials balked at the idea, and a disappointed Conrad tossed his intended murder weapon, a musket, into a well not far from the White House.

In the summer of 1862, the preacher caught the attention of authorities with his school’s commencement exercises. Students made fiery speeches for the South, and some flaunted secession badges. Conrad hired the U.S. Marine Band for the occasion and persuaded them to play “Dixie.” The crowd cheered, and ladies stood on chairs and waved handkerchiefs.

The whole capital heard what happened, and the provocation proved too much. Conrad was arrested and jailed in Old Capitol Prison, on the corner where the Supreme Court now stands. He won parole fairly quickly—authorities, who knew him only as an agitator, didn’t learn of his more serious crimes—and “proceeded to get into more mischief without delay,” as he wrote.

Over six weeks, he began to make the rounds of prewar friends now in the War Department and military detective bureau, sniffing out Union secrets. But only weeks after his release, he was arrested again and shipped to Virginia in a prisoner exchange.

In the Confederacy, Conrad sought out a longtime friend, Major Dabney Ball, chaplain of James Ewell Brown “Jeb” Stuart’s cavalry. Ball endorsed him to Stuart, who assigned Conrad as a scout. Conrad eventually added the duties of chaplain of the 3rd Virginia Cavalry.

Now wearing a soldier’s uniform, the Reverend claims he had a brief moment of doubt about going to war, asking himself, “Can soldiers be Christians?” This was an odd question given his record of treachery, but he got absolution of a sort from a professor of moral philosophy at the University of Virginia, who convinced him that the South was justifiably fighting in self-defense. With that, Conrad said, he strapped on his pistols and held to his Bible “as sheet-anchor in the mighty storm, whatever might betide.”

Rebel cavalry scouts rode out in front of the army, often posing as civilians or Union soldiers. They probed the enemy’s positions and sometimes slipped into his headquarters. Conrad was a natural for such work; audacious and glib, he was also at home in the saddle and familiar with northern Virginia.

FEW OF STUART’S SCOUTS worked beyond the battlefield, but Conrad was soon sent to the very capital of the Union and proved himself an invaluable asset to the Confederacy. His first charge was to meet French and British agents in Washington and smuggle them to Richmond, where the Confederates hoped to negotiate sorely needed loans. It was a true cloak-and-dagger mission. A gash on Conrad’s tongue and a scar on his left index finger would provide proof of his identity to friendly contacts. After crossing the Potomac at a Confederate signal station east of Fredericksburg, Virginia, he traveled to Washington on foot and by rented horse and slipped into the city. Next day he sought out the foreign financiers at Willard’s Hotel, the epicenter of Washington life.

Willard’s was jammed with army officers, politicians, and businessmen eager for a slice of the government’s vast wartime budget. Conrad made his way through the crowded lobby without being recognized. Meeting the foreign visitors in a room upstairs, he stuck out his tongue and waved his finger to prove who he was.

The foreign agents carried papers related to the possible deal. According to Conrad’s memoirs, he had a friendly cobbler hide these in the heels of their boots. He and the foreign agents then left the city, reaching the house of a sympathetic Maryland farmer at midnight. Conrad paid an old slave a ten-dollar gold piece to guide them across a little-known ford in the Potomac. After a harrowing nighttime crossing, Conrad sent the foreigners on to Richmond, while he returned to Washington and expanded his spy business.

Following President Jefferson Davis’s instructions, Conrad set about devising a reliable way to pass information secretly to Richmond. He enlisted two country doctors who could travel without being suspected. One had a son who ran a store near the U.S. Navy Yard, on the eastern edge of Washington, where the doctor could pick up material. He would relay it to another doctor who lived some 15 miles south and could send information over to the Confederacy via a safe river crossing. In time, more collaborators were recruited, and “the doctors’ line” grew into a key intelligence link. When Conrad visited Richmond, Davis personally congratulated him, according to the spy.

Conrad ran his operation in a high-walled mansion blocks from the White House, the home of Confederate sympathizer Thomas Green, whose son was in Conrad’s brigade. Informants left messages for him beneath the steps of the porter’s lodge at the house. He regularly sent Richmond the Washington newspapers, which were full of details about troop movements. He also cultivated War Department sources, one of whom left classified reports on his desk for Conrad to pick up as he strolled by at lunchtime.

While he prepared each of his missions with great care, Conrad put himself at great risk as he repeatedly slipped in and out of Washington. He posed as a businessman and even as a Union chaplain, and sometimes disguised himself with a beard. To defeat the Union, he said, he “would have crept into a cannon and been fired into fragments.”

Conrad’s spy network delivered vital information for Southern generals. After Lincoln replaced the slow-moving Major General George B. McClellan in November 1862 with Major General Ambrose Burnside, Conrad learned that Burnside planned to march south by way of Fredericksburg. The news was too important to leave to a courier, so he himself crossed the river and rushed to Confederate general Robert E. Lee’s Fredericksburg headquarters. Armed with that intelligence, Lee in December threw back Burnside in the Battle of Fredericksburg, one of the most lopsided victories of the war.

Following the great Southern victory at Chancellorsville in May 1863, Conrad desperately tried to engineer the Rebel capture of Washington. As Major General George Meade moved to block Lee’s push north, the spy hoped to reach Jeb Stuart, who was sweeping past thinly guarded Washington, and urge him to dash in and “make the White House his headquarters,” as Conrad put it.

He rode to Washington’s outskirts and bluffed his way past pickets, only to find that Stuart had pressed on. Conrad then hurried to Baltimore by rail, hoping to catch him there. But he was too late; though Stuart’s cavalry moved too slowly to reach Gettysburg in time to help Lee, he was too fast for Conrad.

One day a Conrad agent in the office of Lafayette C. Baker, chief of the Federal military detectives, warned that Union operatives were on the spy’s trail. That very night, Conrad gave a boat captain $100 to smuggle him downriver to safety in Virginia. Next morning, when Federal officials inspected the boat as it passed Alexandria, he posed as a crewman cooking breakfast. The ruse worked, and the captain dropped him in King George County at Boyd’s Hole, a spot some 50 miles below Washington.

When Conrad rejoined his regiment, Stuart said he had done so well in Washington that he should formally become a spy. With Jeff Davis’s approval, the preacher-turned-scout joined the Confederate Secret Service. He recruited a Dickinson College classmate, Captain Mountjoy Cloud of the 7th Virginia Cavalry, and together they went to work at Boyd’s Hole. Because this was a favorite roost for bald eagles, they named their new riverside base Eagle’s Nest.

In early 1864, Conrad was sent to determine whether Burnside’s Union corps, assembled at Annapolis, was going to mount a naval expedition down the Atlantic Coast, or march by land to join Major General U. S. Grant’s army as it headed south toward Richmond. His memoirs offer a dramatic account of his sleuthing: He crossed the Potomac in the darkness with muffled oars and made his way to Annapolis. Wearing his clerical outfit, he eavesdropped in hotels, at the U.S. Naval Academy, and along the docks. He satisfied himself that no sea operation was planned; Burnside would soon be on his way to Virginia with Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant. When Conrad’s colleagues in Washington confirmed this, he sent the news to Richmond. He said he then returned to Virginia and personally delivered the message to General Lee in the field.

Davis soon dispatched Conrad on another mission. This time, after crossing the river, he found Union guards at every crossroads. Trying to slip past, he was surprised by a squadron of blue cavalry. He tried to bluff his way through but was arrested and taken to Point Lookout prison camp, at the mouth of the Potomac.

The Federals, however, didn’t realize whom they had caught; they didn’t search or interrogate him. Conrad immediately planned an escape. According to his memoirs, he faked smallpox in order to be transferred to the lightly guarded hospital for prisoners with the disease. He slipped away and crossed the river to Virginia, where he quarantined himself for several weeks.

Next came Conrad’s most audacious wartime escapade: an attempt to kidnap Abraham Lincoln. He and Mountjoy Cloud had talked over the idea at length and became convinced it was possible. With a couple of henchmen, they would grab the president during one of his short treks to the Soldiers’ Home, where he often spent summer nights. Then, Conrad wrote, they would smuggle him south and “hold him as a hostage for peace.”

According to Conrad, he led his band of accomplices to his Washington safe-house mansion in September 1864 and settled in to firm up plans. Even though he was on the Union spy chasers’ most wanted list, he idled with Cloud in Lafayette Park, across Pennsylvania Avenue from the White House, studying Lincoln’s movements.

Before they could spring their surprise, however, things went awry. As they watched one day, Lincoln left the White House as expected, but this time he was escorted by a cavalry troop, clattering before and behind his carriage. Apparently detectives had reinforced his guard after picking up rumors swirling in Washington saloons about a threat to the president (rumors likely centered around Confederate cavalryman John Mosby). Frustrated, Conrad abandoned his scheme.

SECRETS FLOWED BOTH WAYS between the wartime capitals, and in the last winter of the war, Conrad became a counterintelligence agent, trying to intercept Union spy traffic. He also told of leading crews of boatmen out on the river at night to plunder vessels that ran aground near Eagle’s Nest.

Conrad’s spy work ended when the war concluded. The day after Lincoln’s death, a patrol off the USS Jacob Bell caught Conrad at a farmhouse near the Eagle’s Nest. The commander of the Potomac River Flotilla reported proudly to Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles that his men had “arrested a noted guerrilla and spy.”

Conrad was taken once again to the Old Capitol Prison, which was run by Colonel William Patrick Wood, an occasional spy himself. During Conrad’s previous stay at the prison, Wood had introduced him to Lafayette Baker, perhaps thinking Conrad could be persuaded to do espionage work for the Union. Now, Wood questioned him about the conspiracy to kill Lincoln. Conrad claimed he knew nothing. The kindly superintendent believed him and soon set him free, even lending Conrad his horse.

Conrad’s adventures were not over quite yet. With Conrad back in King George County, U.S. cavalry searching for Lincoln’s assassin swooped in with orders to arrest what the lead officer declared was “a very desperate guerrilla.” Conrad said that as he was transferred to Richmond, he leaped off the train when his guards fell asleep. Fleeing west, he skirted Federal outposts and hid with friends in the Blue Ridge Mountains and the Shenandoah Valley. Only months later did Conrad feel safe enough to come back to his old haunts. With the war over, the Reverend returned to his career as an educator. In the 1880s, he served as president of the agricultural college that became Virginia Tech. But when he died in 1905, he was back in Washington—working as a statistician for the same federal government that he had conspired against as one of the Confederacy’s best spies.

Ernest B. Furgurson, a regular contributor to MHQ, is a journalist and author who has written several books about the Civil War, including Not War But Murder and Freedom Rising: Washington in the Civil War.