In the fall of 1862, Union forces began yet another forward movement toward Vicksburg, Miss. Both the United States and the Confederacy realized that Federal forces had to take complete control of Vicksburg and the Mississippi River to win the war. Union forces already controlled much of the river, and in the spring, Admiral David Farragut tried to capture Vicksburg. Receiving little support from the Union Army, however, he had failed. Union forces thus controlled the Mississippi River north from Vicksburg and south from Port Hudson, La. Some 130 miles of it remained in Confederate hands.

Understanding the situation, Navy Admiral David D. Porter asked Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman in November 1862 whether Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant had any plans for military action against Vicksburg. If so, did he want Porter to cooperate with him? Porter said he knew little about Grant’s plans. Sherman was in the dark, too, but he agreed with Porter that “a perfect concert of action should exist between all the forces of the United States, and all should work together.”

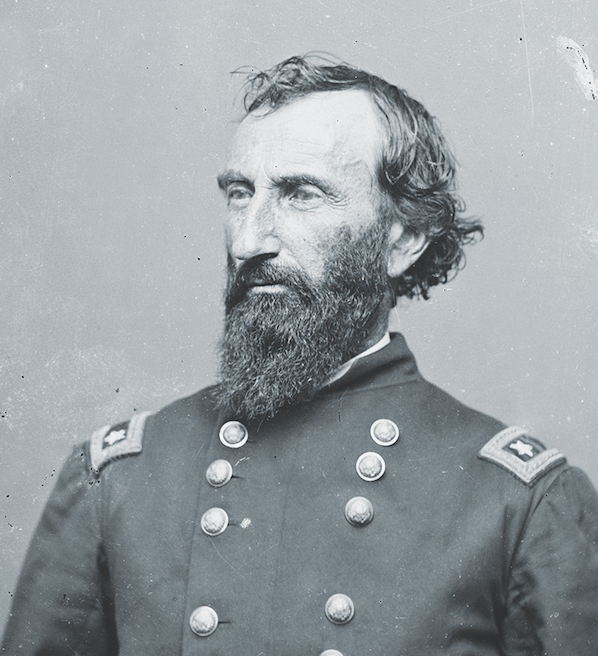

Sherman and Porter were more than willing to work together to take Vicksburg. Grant was not convinced it would be that simple, however. Volunteer major general and former Congressman John McClernand had convinced President Abraham Lincoln to allow him to recruit troops in the old Northwest, and then lead his independent force to capture Vicksburg. Porter and Sherman did not trust McClernand, and Grant and General-in-Chief Henry W. Halleck did not believe that he had the necessary military talent to make an effective offensive.

As was the case in every action he took in the Civil War, no matter the problems, Grant did not delay. He and Sherman had already cleared Confederate forces out of northern Mississippi, so he, and even more significantly Halleck, on December 12, ordered Sherman to ignore McClernand and move against Vicksburg. Grant told Sherman, who was then in northern Mississippi, to quickly move to Memphis, taking along one division of the command he already had. Once he reached the Bluff City, he was to take over all the forces there, including those that had been forwarded to the city by McClernand. Grant told Sherman to “organize them into brigades and divisions in your own way.” Then, as soon as possible, he was to move down the Mississippi River “and with the cooperation of the gunboat fleet under command of Flag-Officer Porter proceed to the reduction of that place…as your own judgment may dictate.”

Sherman quickly wrote back to Porter, and he agreed with Grant’s call for swift action. “All this should be done before the winter rains…,” Sherman said.

Sherman arrived in Memphis on December 12 and planned to move south into Mississippi on December 18. He wrote to a friend on December 14, expressing his excitement: “My hobby always has been the Mississippi, and my faith cannot be shaken that the possession of this great Artery will be the most powerful auxiliary in the final steps that must restore the Sovereign power of our Governnmt [sic].”

Grant, meanwhile, initiated plans that the forces he commanded would continue to try to hold Confederate forces north of the Vicksburg, so Sherman could be successful in taking the Hill City. Grant was to move his 40,000-man army south along the Mississippi Central Railroad and hold Confederate General John C. Pemberton at Grenada, while Sherman moved down the Mississippi River and captured Vicksburg.

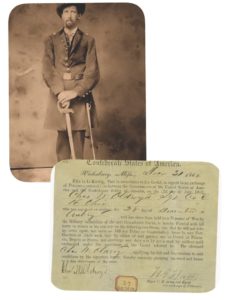

As was the case in so many Civil War engagements, there were other matters that required Grant’s and Sherman’s attention during the late fall and early winter of 1862-63. Sherman continued his battles with reporters, to the point of banning them from his military activities and then issuing the first court-martial of a reporter in American history. Sherman also threatened to retaliate against any Confederate guerrillas who bothered his attacking force. Even more significant was Grant’s use of black soldiers authorized by Lincoln’s January 1, 1863, Emancipation Proclamation.

In November 1862, Grant had already appointed Chaplain John Eaton as Superintendent of Negro Affairs in his Army of the Tennessee. Sherman, however, resisted including black soldiers in his army and used them only as pioneers. And Grant made the uncharacteristic blunder of issuing special orders to expel all Jewish people out of the Mississippi Valley. He spent the rest of his life making amends for the error.

Sherman had around 30,000 men, and he packed them into Admiral Porter’s transports. He was confident that Grant was moving southward to attack Vicksburg from the east while he attacked it from the river in the west. Then he heard rumors from one of his subordinates, Brig. Gen. Morgan L. Smith, “that Holly Springs [a key Union supply depot] had been captured by the enemy.”

Major General Earl Van Dorn’s 3,500 horsemen had left Grenada on December 17, and early in the morning of December 20, Van Dorn surprised the 500 Union soldiers at the Holly Springs supply base. He took what his men could carry and left the rest a smoking ruin.

During this same period, Maj. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest inflicted significant damage on Grant’s flow of supplies from Tennessee and Kentucky. He destroyed sections of the Mobile & Ohio Railroad. Grant had to withdraw north to Grand Junction, so Sherman was left pushing forward toward Vicksburg by himself. Meanwhile, Pemberton prepared to leave Grenada, mimicking by land Sherman’s movement on the river. A Union and a Confederate force were racing each other toward Vicksburg.

Sherman continued to believe that Grant would join him at Vicksburg and argued that “Chickasaw Bayou is our line of attack, and we cannot do or attempt nothing [sic] till we make a lodgment on the hills at its head.”

Nearer the city, Federal Navy Lt. Com. Thomas O. Selfridge Jr. was leading a number of gunboats, including Cairo, up the Yazoo River. The sailors saw Confederate torpedoes in the water and attempted to blow them up before any Union vessel hit one. Selfridge placed Cairo in the lead because of its size and in order to drive away sharpshooters. Suddenly an explosion sent Cairo to the bottom of the river. For the first time in naval history, a torpedo had been electronically exploded to destroy a boat. Thus the Federals opened the Yazoo River channel, but only as far as where the Chickasaw Bayou entered that river. More importantly, the Confederates had limited the sites of Sherman’s attacks to the bottomland bordered by the Mississippi River, the Yazoo River, and the Walnut Hills.

On December 19, Confederate President Jefferson Davis and General Joseph E. Johnston, the commander of the Departments of Tennessee and Mississippi, arrived at Vicksburg to try to deal with the crisis. The two leaders carefully inspected the city’s defenses from Snyder’s Bluff north of the city to Warrenton below. Johnston was hardly impressed with what they saw, but Davis was pleased. Then the two men moved north to catch up with Lt. Gen. John C. Pemberton.

The presence of such distinguished guests raised morale in Vicksburg, and the city celebrated the occasions with a round of social events. In the midst of the gaiety, a mud-splattered courier, delivered a message to Maj. Gen. Martin L. Smith, that 81 Union vessels, both gunboats and transports, were steaming down the river. William T. Sherman’s invasion was coming to pass.

General Smith had about 5,000 volunteers and soldiers in the city, and he quickly had to decide what to do with them. Should he defend the Walnut Hills on which Vicksburg was located? The Confederates had dug in nine batteries on Snyder’s Bluff 12 miles north of Vicksburg to anchor that geography. Or, should Smith man Vicksburg’s main defenses around the city? He decided on the first option, to hold the Hills and the bluff. That way he would keep control of the entire Yazoo River Valley and also prevent the Federals from cutting the Southern Railroad, east of Vicksburg—the main supply and communication route into the city.

On Christmas Day, Smith filled the Walnut Hills defensive works with soldiers and placed West Point graduate Stephen D. Lee, an artillerist by profession but now serving as an infantry leader, in command. Confederate engineers had already built trenches at the foot of the bluffs, that went almost straight up 200–300 feet. Lee could not have been happier in his defensive position: the right anchored on Thompson Lake, east of Chickasaw Bayou, the left on the Mississippi River to the west. He chose five places on the bayou where he thought Sherman would particularly want to cross, and he then reinforced three of these most vulnerable places. All the advantage lay with the Confederate defenses under Lee.

Sherman’s men had almost insurmountable barriers. As Porter put it: “Sherman at every point encountered obstacles of which he had never dreamed.” In order to get to the hills from the Yazoo River, Union soldiers had to cross deep water and navigate sucking swamps. Then they had to cross a Confederate abatis, felled-trees which only made the geography of the place even more impassable. Then there was another abatis beyond the bayou and just in front of the hills. Confederate cannons and rifles covered the area, and signal towers at both ends of the hills allowed the Confederates to see everything that the Federals were doing.

Sherman believed he understood the topography, but Confederate engineer Major Samuel H. Lockett noted that the area was a “series of irregular hills, bluffs, and narrow tortuous ridges apparently without system or order.” Sherman had some 30,000 men to attack the roughly 6,000 Confederate defenders, which would increase to 14,000 with reinforcements from north Mississippi. Confederate morale increased as they realized how difficult a task the Federals had. Lockett had already strengthened the natural defense by building “a system of redoubts, redans, lunettes, and small field works, connecting these by rifle-pits just so as to give a continuous line of defense.”

Meanwhile, Sherman’s boats had tied up at Milliken’s Bend on December 24, 1862. His troops sang holiday carols and patriotic songs far into the night to deal with their jitters. On Christmas Day, Sherman began his attack. He ordered one of his subordinates, Maj. Gen. A.J. Smith, to use Brig. Gen. Stephen Burbridge’s brigade, to cut the 90-mile long Vicksburg, Shreveport & Texas Railroad west of the Mississippi River. The brigade left at dawn, accomplished its railroad raid, and rejoined Sherman at Milliken’s Bend the day after Christmas.

Meanwhile, Sherman’s army and Porter’s navy used this time to move downriver from Milliken’s Bend to Young’s Point, so that the vessels would be able to anchor opposite the mouth of the Yazoo River. Sherman and Porter enjoyed Christmas Day together on Porter’s boat, Black Hawk, making final plans for the attack the next day.

Sherman had organized his 30,000 soldiers into four divisions under Generals A.J. Smith, Morgan L. Smith, George W. Morgan, and Frederick Steele, and he included eight batteries of artillery for these units. Crowded on the transports, the Federal army left Young’s Point at about the same time that Burbridge’s brigade was returning from its raid. Transports carrying Morgan’s division led the attack force. Then came Steele’s division, which joined Morgan at the Johnson plantation house, two miles away. Morgan Smith brought up the rear. Before it could join the attack, A.J. Smith’s division had to await the return of Burbridge’s brigade.

Stephen D. Lee worried that the Federals would attack his troops before he received reinforcements. He ordered Colonel William T. Withers to take two Louisiana regiments, two Mississippi companies, and two howitzers to confront the four Federal divisions and six artillery pieces. The Confederates established themselves in some woods along Chickasaw Bayou, and the Federals had to fall back. Shortly after, the Confederates had to retreat, too. The Southern artillery force, however, had slowed down the Federal advance, so it had accomplished its mission. Unfortunately for both sides, the weather quickly turned cold, it began to rain. Neither army could light fires, so the men suffered through a horrible night.

The next day, December 27, beginning at 7 a.m., Sherman’s three divisions slowly moved forward. Colonel John F. DeCourcy’s brigade of George W. Morgan’s division put so much pressure on the Confederates in the center that Withers had to fall back into the main line, and Morgan and the other Federal units consolidated their positions during the night.

Sherman’s force made little progress; they never even reached the Vicksburg bluffs.

Sherman noticed that the trees had water stains on them, 12 feet high, warning him what heavy rain could do to his attack. He could also hear trains delivering Confederate reinforcements from northern Mississippi to Vicksburg, some 8,000 Confederate soldiers. By dawn December 27, these additional men had filled gaps in the Walnut Hills line.

On Sunday December 28, a blinding fog rolled in. “It was so thick that vessels could not move; [and] men could not see each other at ten paces.” It cleared, and DeCourcy’s brigade of Morgan’s division went on the attack, but stopped short before a substantial field opposite Chickasaw Bayou. DeCourcy was taken aback by formidable abatis, and he stopped his advance and fought an artillery duel with the Confederates.

Morgan Smith’s division, meanwhile, was busy trying to open paths through the felled-trees when he took a shot in the hip, serious enough to keep him out of action until October 1863. General David Stuart took his place saw the impossible nature of attacking the bluff to his front. Stuart told Smith how evaluated the situation as desperate, and Smith agreed. He stopped the attack.

That night, Sherman completed his final attack plan. Morgan’s division was to attack at the Chickasaw Bayou, while Morgan L. Smith’s division, now under A. J. Smith, would attack the center of the Confederate defense line at Indian Mound. George W. Morgan was thrilled when he learned that his unit would be making the main attack, responding boastfully to Sherman: “General, in ten minutes after you give the signal, I’ll be on those hills.”

Morgan, though, now made a major mistake. He determined to establish a bridge across Chickasaw Bayou. He put some Kentucky troops to work on this task only to realize that they were not bridging the bayou but another nearby body of water. It was almost dawn before the Kentuckians actually began building the correct span, but in the light of day, the Confederates could see what was happening and began to shell the Union soldiers. His surprise lost, Morgan decided he had to move from the bridge and attack down the nearby Lake House Road.

This attack began December 29 at 7:30 a.m., with a noisy artillery duel that had little effect on either side. Morgan called Sherman to the front to tell him that the attack was hopeless. Sherman said nothing, but then he pointed forward and grimly said; “This is the route to take.” It was the same attack route he had ordered before.

Sherman had made his decision, and his subordinates needed to obey. Sherman said: “Tell Morgan to give the signal for the assault; that we will lose 5,000 men before we take Vicksburg and we may as well lose them here as anywhere else.” Morgan ordered DeCourcy and political general Frank Blair to organize their brigades and told Frederick Steele to send another brigade to help with the attack.

At noon, after an artillery barrage, DeCourcy’s and Blair’s soldiers broke into a run, but their lines quickly fell apart from the Confederate artillery and musket fire. The Federals went into the bayou’s freezing waters with their rifle-muskets held over their heads to keep them dry. Blair’s men crossed the bayou and forced the Confederates out of their two forward skirmish lines. DeCourcy’s force tried to cross the bayou, but found it too deep and had to use the imperfect bridge. Both DeCourcy’s and Blair’s men suffered frightening casualties.

One Federal soldier in the attacking force later described the gruesome tragedy of that day’s combat. He called it a “dreadful slaughter, too ghastly to describe…the terrible screams of the wounded drowned out every command, as they writhed about in the mud with heartrending cries.” The Federals were being disastrously decimated, with the Confederates capturing 21 Federal commissioned officers and 311 noncommissioned officers and men.

The Confederate success did not just take place in the Union middle. Everywhere along the attacking line, Sherman’s men took a savage beating. The battle ended with the Confederates still in place in their defenses. To make matters worse, it poured after sunset. The wounded suffered enormously, and many died lying exposed on the now quiet battlefield. The Federals lost 208 men killed and 1,005 wounded. Confederate losses were only 63 killed and 134 wounded.

Sherman bluntly wrote his wife, “Well we have been to Vicksburg and it was too much for us, and we have backed out.” Meanwhile Jefferson Davis saw Sherman’s defeat as proof that his strategy of maintaining control of the Mississippi River was splitting the old Northwest apart.

With the battle of Chickasaw Bayou over, Sherman went back to Admiral Porter’s flagship, cold, upset, and worried about the terrible bloodbath his troops had just suffered. He kept hoping his soldiers might be able to make some sort of further attack, but on January 2, he realized that there was no hope. The only good out of all this carnage for Sherman and Grant was Henry W. Halleck’s decision, as Federal army commanding general, that John McClernand would not have an independent army but would become a corps commander in Ulysses Grant’s force.

After Chickasaw Bayou, Vicksburg and the Mississippi River remained in Confederate hands. However, the battle demonstrated just what lay ahead for the city after. After Chickasaw Bayou. Sherman wanted Grant to return to Memphis and begin his Vicksburg Campaign once again from there, but Grant recognized the political problems such a move entailed. He kept his troops near Vicksburg, hoping to find a way to capture the city from where he was, on the watery levees. It was another six months before Vicksburg fell, however, and it took brilliant maneuvering on Grant’s part to make it happen, and it took a successful siege of the city to have it fall on that most significant of all American days: July 4, 1863.

Chickasaw Bayou demonstrated that both the Army and the Navy indeed had to work together on the rivers of the nation, the highways into the Confederacy, in order to attain Union victory. Grant and Sherman had realized early in the war just how important the rivers and control of them were to the Federal effort. The two leaders also saw that, as with the railroads, Federal troops, as they had been doing since the beginning of the war, would have to take over steamboats from civilians and use them for moving troops and supplying goods. Because they needed wood to fuel the boats, they were also ready to use soldiers, sailors, civilians, and slaves to cut the lumber into the appropriate size to feed the hungry steamer furnaces.

The Chickasaw Bayou campaign also demonstrated something that was going to create problems for the Confederates throughout the rest of the war. The political and military relationship among their leaders was constantly troublesome. Pemberton, Johnston, and Davis could not agree on how to defend Vicksburg. The argumentative military-political relationship exemplified the basic weakness of the entire Confederate war effort.

Before the final capture of Vicksburg in July 1863, Grant revolutionized the war by incorporating Black soldiers. Their presence meant that, for the first time, Whites heard about Blacks in a capacity other than as slaves. The result was that Southern Whites were frightened, while Southern Blacks were encouraged to see greater possibilities for themselves in the future. The social and economic way of life in the South underwent a new challenge.

The Confederates also realized that they would have to utilize guerrilla warfare against the Federal army on land and on the waters. Sherman and Grant considered such warfare to be unprofessional and retaliated accordingly. Sherman, for example, leveled the town of Randolph, Tenn., in retaliation for Confederate guerrilla activity. Confederates were appalled at that, but were powerless to stop Federal retribution.

One modern historian, James T. Currie, expressed it well: “[T]he War had caused a tremendous upheaval in all that existed within the city.” Of course, some of this change did not take place until after Vicksburg’s capture in July 1863. Other problems developed as a result of the Union victory, the Federal occupation, and later Reconstruction. As historian Bradley R. Clampitt has phrased it: “The war and occupation transformed the daily lives of all Vicksburg residents.” The city was never the same again, nor was the war itself.

John F. Marszalek is the executive director of the Ulysses S. Grant Association. He has authored Sherman: A Soldier’s Passion for Order and Commander of All Lincoln’s Armies: A Life of General Henry W. Halleck.