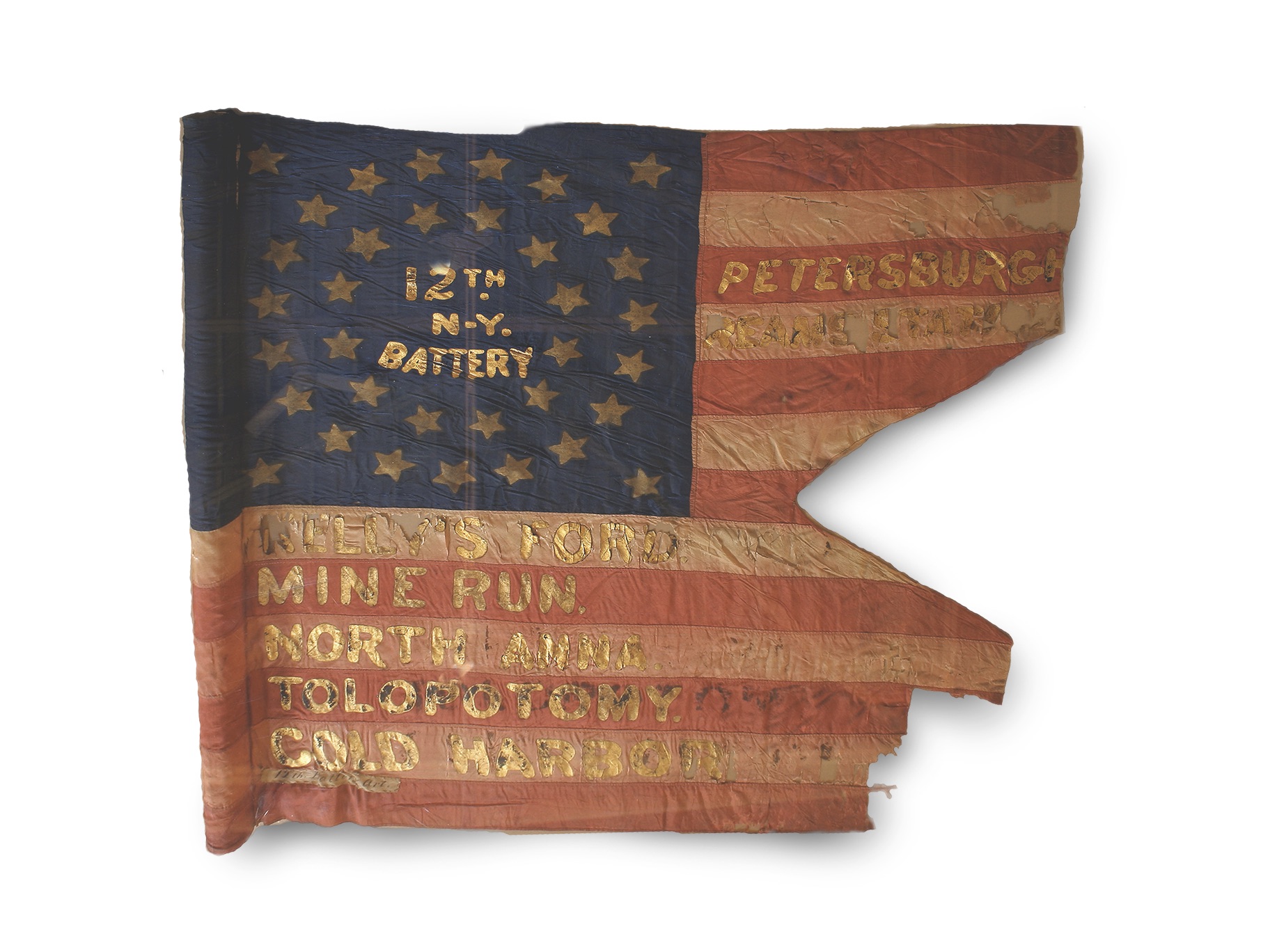

June 21, 1864, marked the first day of the Battle of Jerusalem Plank Road, the opening engagement in what would become the Army of the Potomac’s nine-month siege of Petersburg, Va. For Elisha Davis Conklin, though, it was a relatively peaceful day. That afternoon, Conklin and his fellow gunners in the 12th Independent Battery, New York Volunteer Light Artillery took advantage of an opportunity to explore the land near their position along the army’s 2nd Corps’ lines. Conklin, who had enlisted in October 1861, was a first sergeant in the 12th New York, a few weeks shy of his 25th birthday. Coming upon a large farmhouse with “a large garden of all kinds of vegetables,” he began bartering with the farmer for some of his produce, later writing, “We got all we wanted and [the farmer] also was well pleased. The boys…traded coffee, socks, drawers, and many trinkets; we had a fine dinner.”

The frivolity didn’t end there. After dinner, Conklin bought a hive of bees from the farmer. “I took one of my detachment that was used to handling bees,” he would write. “He took a blanket, set the hive down very carefully on it, and when he got to the Battery he scraped the clover all away so the ground was clear. Then he lit a fuse, set the hive over it very carefully—so as not to disturb the bees—and in ten minutes he took nearly twelve pounds of honey out of the hive, and you could not see a live bee around.”

Conklin watched in amusement as another detachment followed suit.

“[W]hen they set their hive down on the coarse clover that lay on the ground, the bees crawled out from under their hive,” he wrote. “They began to crawl up the fellows’ legs that were standing around, and they began to curse and holler for the bees were stinging them. They were hollering like bloody murder. Jack had told our detachment to keep away from the crowd that were waiting to get their honey and we would see some fun. Sure enough, for they had shook the bees all down so they would crawl out, and were pulling off their clothes, turning them inside out and shaking them…”

After seven weeks of constant fighting, and facing the likelihood he would see action the following day, the evening’s merriment was a welcome respite for Conklin. But like the bees in that hive, his world was about to be wrenched apart. During the afternoon fighting on June 22, Confederate infantry charged and overran the 12th New York’s guns, taking several Empire State gunners prisoner, including Conklin.

By the end of July, Conklin found himself a captive at the Confederates’ Camp Sumter prison camp in Andersonville, Ga. An unfortunate 13,000 or so Union prisoners would die at the notorious Andersonville while it was open, but Conklin survived not only a five-month stay there but also the war. He would, in fact, live another 65 years.

In 1926, four years before his death at the age of 91, Conklin compiled his memories of Andersonville, the Civil War, and that fateful June at Petersburg—derived from letters and journals he had kept—in a typed manuscript, portions of which are published below for the first time. [Conklin’s original text has not been edited, but paragraph breaks have been added for readability.] His story provides touching insights into the brotherhood among soldiers, the tragedies of death and disease in prison camps both North and South, and the human resilience and resolve to survive against all odds.

We were ordered out at 2 A.M. June 22nd, 1864. The Pioneers were sent up ahead of the Battery to cut a road through the woods and underbrush, and to throw up some embrasure for the Battery. They threw some for the five right Pices, but none for my Pice, which was on the extreme left of the line of Battle, so we were placed 50 yards from the five right Pices and had to put up our own protection ourselves. By 8 A.M. we were ready for action and we commenced firing at about once in from 15 to 20 minutes, and I kept my Pice well sponged so it would keep cool, for I did not know how quick I might want to use it faster.

The infantry on both sides had kept a pretty sharp firing-up until after 2 P.M. Then the artillery on both sides opened, and then I slackened up until the artillery firing began to die down, then the Rebel infantry began to work towards us, and I commenced to fire into their lines and they were coming pretty close then. I used a case shot without fuse, then canester, and we were firing as fast as we could, and in a short time a batch of Rebels came on to us from Front and Rear, and as they were planting their colors on our works, we were firing into their ranks, when they took us prisoners. Then they rushed us into their lines at a double quick for 1/4 of a mile, then put us in a barnyard and about 9 P.M. put us in an open field and put a strong guard over us.In the morning of the 23rd they took us down to Petersburg and put us on an Island and let us buy some bread, which we paid nine dollars for the nine loaves. Then we were put on the cars and sent to Richmond and put in Libby Prison. Then we washed up—they began to send squads in to search us. We had to take off all our clothes and they would search them. Two of our detachment had been searched and they were dressing on the other side of the table where I was undressing; they gave me a tip to pass my valuables over to them, and I passed my gold watch, ring and $80 in greenbacks and the Rebels never saw them pick them up; they were two pretty handy fellows, their names were Kelly and Richards and Richards was a sleight-of-hand fellow. So they saved all of my valuables and the rest of my detachment lost everything. The Rebs had told they would get them when we went out, but they never got any of them. We were sent to Belle Island and laid there until the 28th of June, then sent to Manchester. The 29th put in cars and sent to Lynchburg. The 30th of June we left for Lynchburg and marched five miles to the River Stanton, laid there all night.

July 1st – a rainy day – marched 20 miles. Got no rations.

July 2nd – marched all day, got four corn dodgers. Not a drink of water today. Marched 20 miles.

July 3rd – marched 20 miles, several gave out, left them behind, no rations.

July 4th – marched 15 miles, an awful hot and dusty day; got to Danville 4 P.M. Water once today, but no rations. They put us in a warehouse and laid here 36 hours until the 6th; then put on cars and sent to (I think the name of the place was) Shilotta and lay there all day, in the cars most of the time. Put in cars again and rode all night. We had one meal in 24 hours.

Morning of the 8th we arrived in Augusta, took us off the cars and to a goose pond to wash. Could not drink the water. Put on the train again and run out into the country. Don’t know where the guard said they were going to take us, to some place where there was a stockade, but they had orders to send us back to Augusta again. We were in Augusta the morning of the 9th. They ran us where they had long flower beds and walks in their garden that came clear to our car, and there were four colored women watering the flowers. We were dry standing still as we had been without water; we saw some white ladies looking at our car and we asked them if they would let the colored women fetch us some water as we had not had a drink all day. She let them bring us some; we were drinking as fast as we could—some of the boys filled their hats—she said, “It ain’t because I like you, but I have three sons in the Southern Army and if they want a drink sometime I hope they get it”; but a couple Rebel officers came along and stopped the colored women bringing water.

The next stop we made the guard drew rations, but we got nothing. When night came we laid on a tressle in a marsh overnight. I told my men that were taken prisoners with me that if the guard went to sleep, I would cut the sack from him. My boys were so hungry, they kept watching for that grub; I got it and we ate all the corn dodgers the guard had. When morning came the guard says to me—“Did you see anyone take my haversack?” I said, “I wasn’t here to watch your haversack.” In a short time he said to me, “Come with me and we will see if we can see any crumbs on any of them.” He did not find any and he said: “We have been running around several days trying to get you in some stockade, now we have orders to go to Andersonville Stockade, and I will get even with you before we get there….”

The officer asked me if I had the names taken. I said I had, and in a few minutes along came our guard—the one I had cut the haversack off from—and he had two officers with him. He said, “You are the ones I am looking for, I thought you had gone into the stockade.” One of the officers asked the guard what they wanted of us. He said, “I drew rations the other day and they came and stole my haversack and took all my corn dodgers. I told them I would get even with them before they went into stockade.” The officer said, “what do you want?” The guard walked along looking us over, stops in front of one of the prisoners that had on a pair of officer’s boots and he said, “I give you two minutes to pull them off; if you don’t I’ll blow your head off.” The officer said, “Take them off or he will shoot.” So he got the boots. Then he went into stockade.…

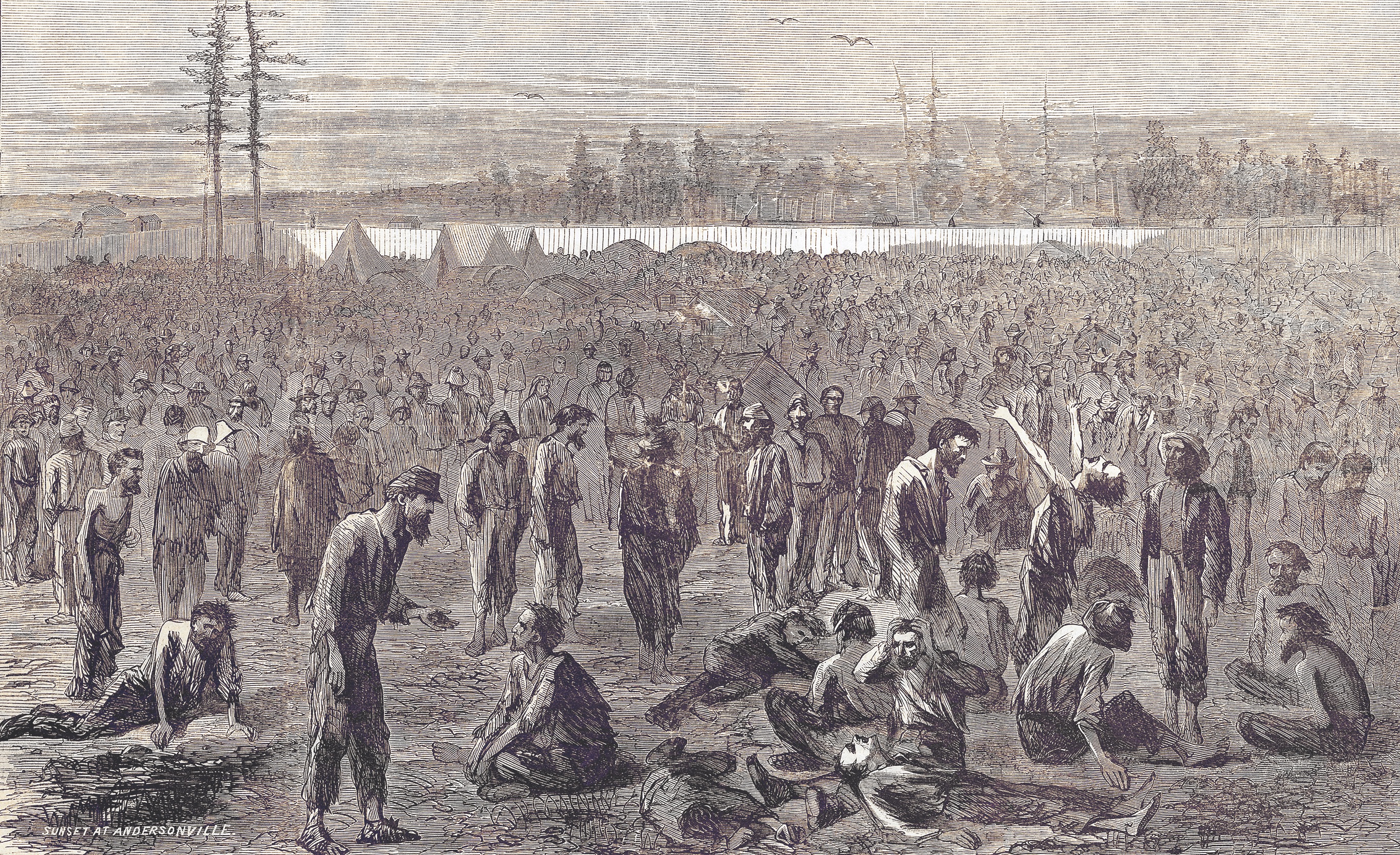

This is about the way we would get our rations; we were counted in the morning, but it was no telling when we would get our grub, maybe 8 A.M. and maybe none to-day and by noon to-morrow we would have gone two days without grub; then the first meal would be corn bread, sometimes for your first meal would draw molasses and the next meal would be mush, so you did not get any molasses to put on your mush. Next day you might get fresh beef—nothing with it. Many days we only got one meal a day, which might be cornbread—that is the way we got our meals. That is the way they made models of us, the kind you would see laid in the dead line every day; one day there were 117 laid in the dead line for 24 hours.

One time some ladies took a peek over the top of the stockade and when they saw those poor fellows lying there, with eyes open, chin dropped, grimey and skinny, those women let a scream out and dropped out of sight. Then to see the way they were taken to the cemetery. They were thrown into wagons—one on top of the other—until the wagons were heaping full, some arms hanging over the side, others with legs hanging out—it was a hard looking sight. And just at that time so many were dying in prisons, and we were informed by prisoners that had just come into the stockade that the men who had charge of the exchange of prisoners on both sides had stopped the exchange because the Southerners did not want to let a colored man be swapped for a white man. The North wanted to exchange all sick and wounded, either white or black that had been in Prison longest. They could not agree on the paroling so it was stopped.

I was talking with a colored prisoner in Andersonville who only had one leg; he said that every colored man in the Pen would willingly stay to the last man to have the exchange go on.

There were eleven hundred of us that started away from Belle Island, Va., the 28th of June. We were in cars most of the time up until mid-day July the 11th, P.M. They were running us around trying to get us in some stockade.

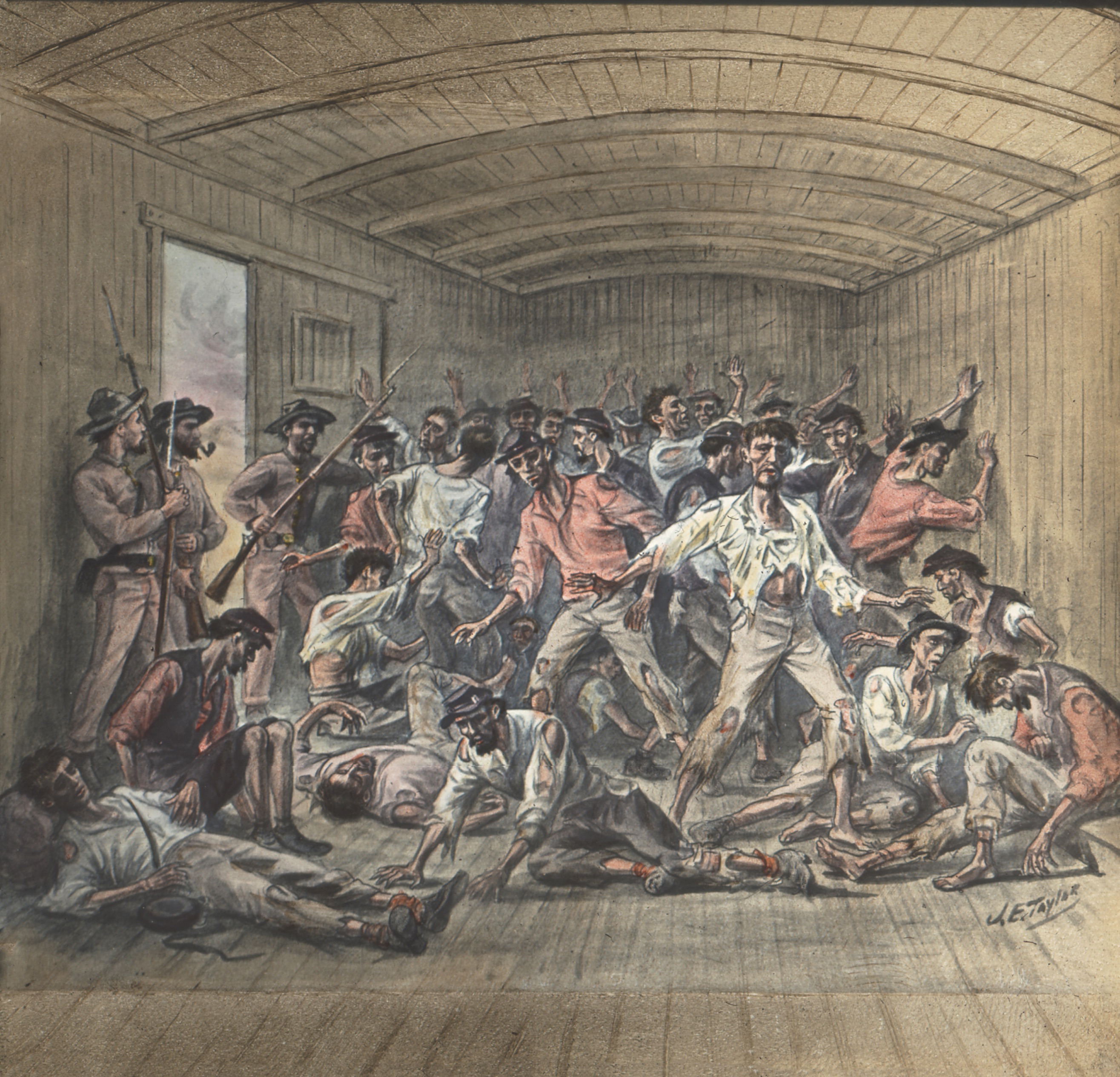

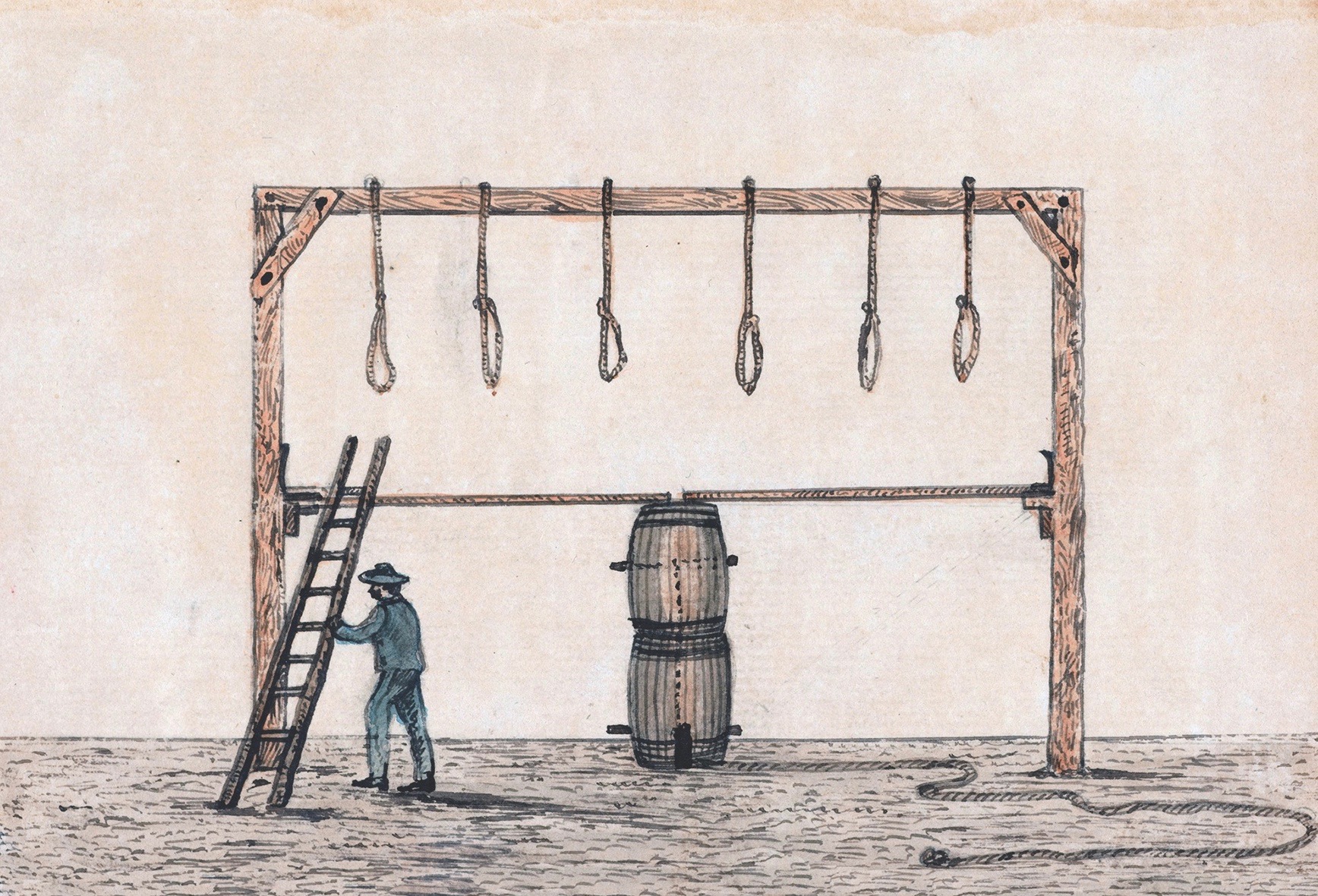

Here is how things would look to you as soon as you got into the Stockade. I had only got inside when my friend, Dawson and I, stopped to see six men hung. They were murderers and raiders. While watching the crowd you would wonder if you would ever get out alive. Some so black and dirty, many with clothes nearly all gone, clothes all rotted away. Many had traded their boots for something to eat, or sold the legs for water buckets. Many had no soap or a rag to dry themselves with. There was about 30,000 of us on the day we went in. Now the hanging is over (one of them broke his rope and ran into the crowd, but they brought him back and hung him).

There was no more murdering or raiding done, so my friend and I started out to buy some dishes and something to cover ourselves with. He had been in the stockade about forty days and was pretty well posted. He took me to a man that they called a dealer. I got a frying pan and some of the old canteens and we melted them apart and made dishes of them. I paid sixteen dollars for a blanket and three dollars for a grain sack. We tore up handkerchiefs to fasten them together and Ike (my mate) told me if I kept a lookout and could get hold of a dead prisoner, carry him over and lay him in the dead line and get a card for him, in the morning they would let four take him out to the dead house and they would all get some wood to carry in. Wood was a scarce article. Our bugler found one the first night and three of our mess went out with him in the morning. So we had wood enough for two weeks. The bugler and the boys had another one in two days and this time they brought sticks enough to fix up our covering. So we had pretty good covering to keep the sun off us. By lying with heads together four in a row, we would lay under there day times and night time stroll around through the grounds, and the bugler and the boys were on the lookout every night.…

If it was a rainy day, it might be bath day, for you wouldn’t get a chance to take a bath only when it rained, for the stream that ran across the stockade was so shallow that you couldn’t take much of a wash in it. So when it rained we could get a good bath. That was the time we could wash out clothes also, but other times it was so shallow we could not get much of a bath or wash clothes. Our clothes got so rotten they would not stand much rubbing. About every day we would take and louse ourselves. If the sun was hinting we would pass the time a lousing; take our clothes off, turn them inside out and shake them; then look them over and pick what we could get off of them; then run along the seams, put our thumb nails together, run along the seams and keep cracking the nitz. Sometime the seams would be pretty white with nitz. We did not get man head lice but always had plenty of body lice, but a man that was in poor health would have brown ones.

We would sit and talk and wonder if we would live to get home and tell our folks how lousy we were in here if they would believe us. Then on Sundays we would talk about what a dinner they would be having and us foolish fellows to have enlisted. So that is the way we would pass the time. Then we would go strolling around the camp to see what news we could get; every day looking for some word of exchange of prisoners.…Every one of us who were in prison any length of time are doctoring for some disability he got while in prison. My eyes got effected there, got the scurvy. Many doctors do not know how many ways we were affected from it, have been bothered with inward piles and bowel trouble which I got while in prison and have had to doctor for them ever since. Lost most of my teeth with the scurvy, and now because I can walk they think I am all right. I am thankful that I have lived so long.

Here are some things that I tried to get through. I asked one of my officers in command at the stockade to let me write to my father. I told him my father had a brother living in Houston, Texas, that had a drug store and I wanted my father to write to him that I am in the stockade and am sick; have the disentary and piles and I have eight men with me that belonged to my detachment and most of them are ailing, and I would like to have him send me some medicine. I got a sheet of paper and envelope from the officer. He told me not to seal it up because he had to read it and if it was all right it would be sent with others, with a flag of Truce through the lines. I took my letter to him to read. He took and sent it, said it was alright and hoped I would get the medicine.

I did not get the medicine. My uncle answered my father’s letter; told him he could not say he was sorry I was there, but all he could say was that he was sorry that there were not more of us in there. So when the officer read father’s letter, he says, “How many men did you say were with you?” I said, “There are eight of us.” He said, “If you will all go out and agree to stay until after the war is over, I will place you all in a good place where you will get good grub and with nice people.” I told him we could not make such a bargain. There originally were nine of us, but one took the oath and went outside and our army took him a prisoner and they had him in jail somewhere, I forget where. His folks wrote to me, wanted I should sign some papers for him so he could get out. I tore the papers up, never heard from him since. We had another man that was true blue; his name was La Barren. The Rebs often came looking for shoemakers, offered to pay them good. We tried to get La Barren to go out, but he would say “Let them go to Hell and make their own shoes.” He was driving the ambulance when captured. He stayed in the stockade until he died. Fine old man.

Before we left Andersonville I had lent some of my money, sold my watch and ring and spent all my money except 85 cents. I felt good that Kelly and Richards had saved those articles for I think it saved my life and my gun detachment of eight men; all lived to get home and all lived 20 years after getting out of prison. Kelly and myself are the only ones living now; I think Kelly is in his 86th year and I have a good start in my 88th.

Now I will tell you how Ike and myself got out of Andersonville. There were one thousand names enrolled to go out in the morning to be paroled. During the night one of the lot that were to go out died, and Ike came over and told me to come over and answer to his name in the morning. I went and when I went through the gate that was all right—when I went into the stockade I did not remember of there being more than one gate—but when I stopped at the second gate Ike was there and he hollared to the gate man to let me through…

We were put in cars and they told us we were going to be paroled. We were in this car about 30 hours without water or anything to eat, and when they took us off the cars they marched us to where they were building another stockade and put us in there. We had no covering and no dishes, so we strolled around in the Stockade. We drew pea soup and we had nothing to put it in, so we got our mess man to hold it until we could borrow something to put it in. After strolling around all night—we could not sleep for as soon as we saw the stockade we knew there was no parole for us. We were broke up. I said: “Ike, make the best of it, I have 85 cents and we will see what we can do.” One of the prisoners told us that there was a crippled Reb that bought stuff of fellows that were going out. They were fellows that were nearly dead and the Rebs were sending them to be exchanged. So we went to the crippled Reb and got a few old tin dishes. Then we got a little sleep, couldn’t sleep much. Then we run across a Bucktail who was in the same fix as we were, and we all got in the same mess. I could hardly get around for I had the scurvey, but the little Bucktail helped me and Ike got a job outside. He had to come inside every night, so Ike and the little Bucktail got some roots and made a stand for me. We got a little iron kettle that held about four quarts. Ike traded some York state buttons, we had polished them and they looked like gold, the darkies we’re glad to get them….

After we three had gotten along nice for a spell—I could get around pretty good again—Bucktail and I thought we would go to the other side of the camp. We went where there was a log laid across the stream and we did not notice that it was the dead line. Bucktail had gotten about halfway across the log and I was just going to get on it when the guard shot him, because that log was a part of the dead line. We got Bucktail out and sent him out in the morning with the dead. Ike came in and asked, “Where is Bucktail?” I replied, “He got on that log to cross the stream and the guard shot him, he fell in the water dead.” Ike felt awful bad for Bucktail was such a nice boy. Ike and I got along nicely for some time, then he began to feel bad. He stayed inside for one day and then went out again. After three days I asked the guard to find out why Ike did not come in. He told me that Ike had been buried for three days. That left me alone and I was going down hill pretty fast myself.

The 28th of November they took the names of about four hundred of us, all sick and wounded, to be exchanged. They took us outside in an open field and kept us waiting all night for cars. It was a very cold night and we were poorly clad, some in a pair of drawers, not one in ten with a shirt. Some no pants, all rotted away; some one coat sleeve gone; all without any covering. Some all crippled up, lots without shoes, lots bareheaded and we all lay nestled together until morning. Then we were all put back in the stockade again and got a dish of pea soup. At 4 p.m. we were called out again and put in cars, taken to Charleston and put in a lumber yard. Laid there all day and the Sisters of Charity fed us twice that day. Then in the morning we were put on cars again, sent back to Florence and put in the Stockade again. Laid there all night, then taken out, given a dish of pea soup and put on cars again for Charleston. Arrived at 8 a.m. and were taken to a rebel boat, “The Star of the South.” We were all day getting thru the blockade. Got aboard a U.S. Boat about 4 P.M. We passed Fort Sumpter just before we got aboard the U.S. boat. When we got on the U.S. boat, they had barrels sawed in two for wash tubs to wash us in. They had men there to scrub us. They took all the rags off of us and threw them overboard. When they got us scrubbed they took us thru the gangway on to another boat, then the helpers would take a blanket and drag it along. There were dry goods boxes strung along. The men had their blankets and as they passed the boxes each box contained one kind of outfit, one overcoats, another caps, etc. until you got your whole outfit. Then we went through another gangway on to another boat. There we dressed ourselves….

Here is where we got something to cheer us up. That was the odor of coffee cooking, the first for some for a whole year, but the most of us six or seven months. Let me tell you it did smell nice. They gave us light grub, but it seemed like the best meal we ever had. Three of the boys got into the store room and ate so much that two of them died by the time we were getting into pretty rough sea….

When they took us off the boat they sent the sixteen of us, that had lain on the deck, to the bath house, where they washed and put dry clothes on us and sent us out to the Parole camp. They didn’t keep me there long. They sent me home quick for after they gave me my furlough papers, they gave me orders to get in line, they were all going home. When we got to the cars in Baltimore, I was all in. The first thing I knew I was in a fire engine house in Baltimore, laying on a cot. I asked the firemen how I came there. They said, “The day before yesterday, just after dusk, one of the boys saw you sitting there all hunched up over by that building. They brought you here and you were trembling like a leaf. Your teeth would chatter like lightening and you couldn’t talk, so we called a doctor and he said you never should have been sent away in such a condition…”

He told them to let me lay there as my nerves had been overtaxed, so the boys had washed me and changed my clothes. They had given me several meals. They saw by my papers that I was going to Amsterdam, N.Y. on a furlough, and when I got up they said they would take me across to my train. I wanted to stop in New York two days and they found out what train would get me there in the morning. They took me to the train and told the conductor I was going to stop in New York two days. The conductor was very nice when the firemen told him what they had done for me and that I was from Parole Camp. He knew I had been a prisoner, so he had me tell him all about the prisons. He made me go have breakfast with him. All I could do for the firemen was to thank them for their kindness. They would not take a cent. I stopped two days at the hospital in New York, then went to Albany for one day, then on to Amsterdam, my home.

While on the cars from Albany, I had to go to the closet pretty often and one of the men that sat close to me said: “I see by your badge you belong to the 12th New York…We have several boys from our town that belong to that Battery.” I said, “You are talking to one of them now.”

He wanted to know who I was. I told him Elisha Conklin, but he said, “He was such a stout and healthy boy.” Then he threw his arms around my neck and this man was Mr. Bronson. Then Mr. Kline, the banker, came over, then a State Representative, Mr. Little. They hoped I would get well and I was asked by all to come and see them.

When I got off the cars my father did not know me. This was the time when I got a furlough at Annapolis to go home and recruit up. I was invited to go here and there to spend a few days and a great many came to see me inquiring about friends, fathers and brothers. Some I knew had died in Rebel prisons; some had died in Andersonville and some in the Florence [Ga.] stockade….

I was [eventually] sent to my battery at City Point, Va. Got there in the evening, 9 P.M. and went to the Commander. He told me I would have to go into the yard. There were several others along with me and I found two others of my company. This was in March and the yard was slushy—a nice place to put one just after coming out of the hospital. We walked around until 12 o’clock. Then two of my company had a poncho and a blanket. We scraped a place to lay on and put some shavings on the ground. We laid there until three a.m. There were barracks on two sides of the camp and there were 300 rebs in these barracks. In the morning we asked the Commander to put us in the barracks. He put the rebs out and put us in; the boards ran up and down and there was an inch or more between the boards. One of the boys spied our Quarter Master pass by and called to him. He went to the Battery and one of the officers came and got us; in thirty minutes we were in our Battery, then we were asked all about the prisoners and our experiences.

Now I have given an account of myself and others who were captured with me. When I got back to the battery I had a commission as Second Lieutenant in the Battery awaiting for me to get mustered in.

In December 1866, Conklin married Clarinda Butler of Cherry Valley, N.Y., a small hamlet not far from Amsterdam. Their first child, Dora, was born in 1867. Six more children survived to adulthood: Elisha Jr (1871), McKee (1874), Proctor (1875), Charles (1877), Fred (1879), and Lotta (1881). In July 1890, Clarinda died of heart failure, just 48.

Moira Ann Jacobs, of Santa Rosa, Calif., is Elisha Conklin’s great-great-granddaughter. She thanks her cousins Arline Hanson, Bill Hanson, and Thomas Collette for sharing Elisha’s original manuscript, and her father, who shared his memories of Elisha when she was a child.