The slender young general stood on a hilltop watching the battle lines form. Some of his troops looked anxiously toward him, wondering if he was leading them to victory or destruction. The veterans among them had no doubt in his abilities. This was the right place, the right time, and Antonio José de Sucre was the right man. Their confidence in him was well placed.

Sucre coolly scanned the enemy lines. He knew it would be a hard fight: The Spaniards outnumbered his revolutionaries 3-to-2 and held the high ground. Worse, they fielded more than a dozen cannons, while he had but one. Regardless, Sucre was supremely confident of victory at what would come to be known as the Battle of Ayacucho.

Antonio José de Sucre y Alcala was born in 1795 in Cumaná, Venezuela, to a noble family that had served the Spanish crown for centuries. After losing his mother at the tender age of 7, the boy began a free but limited military education. Despite their loyal service, Sucre’s ancestors had suffered terribly under royalist governors in the New World. Thus when the Napoleonic wars in Spain created a power vacuum in South America, Sucre joined the Supreme Junta of Caracas, which at the 1810 outset of the Venezuelan War of Independence deposed the royalist regime. Commissioned a second lieutenant, the teen commanded artillery at Barcelona, near his hometown of Cumaná. In 1812, at age 17, he joined the staff of Generalissimo Francisco de Miranda, a legendary commander of revolutionary forces. A year earlier Miranda had returned to Venezuela from exile in Britain at the invitation of a delegation led by Simón Bolívar.

Although some considered Sucre aloof, a genuine bond of affection existed between him and Bolívar. Historian Nestor Alexander Quintero-Aldama suggests their mutual affection may have stemmed from a blood relationship; they were distant cousins, having in common sixth grandparents. That said, there is no evidence to suggest either knew of the family connection.

With the 1812 failure of the First Republic of Venezuela to economic collapse and an untimely earthquake, Miranda signed an armistice with the royalists, prompting Bolívar and fellow revolutionaries to arrest the generalissimo and hand him over to the Spanish. Sucre and other Miranda loyalists went into exile on Trinidad, an island governed by the British, whose alliance with Spain made life there uncomfortable for the revolutionaries. Young Sucre used the time to complete his education. He took a keen interest in international politics.

Sucre was not physically imposing. One source describes him as “thin, like a sword, and only a little bit taller than Bolívar.” Yet his expressive brown eyes and military bearing commanded attention. Sucre possessed a keen intellect and was known for being coolheaded under pressure—though he could also be snappish. When the governor of Trinidad derided revolutionary Gen. Santiago Mariño as an “insurgent,” the hot-tempered Mariño asked Sucre to respond in writing on his behalf.

“Whatever may have been your intention in calling me an insurgent,” Sucre wrote, “I am far from considering that epithet dishonorable, for I remember that Englishmen also applied it to [George] Washington.”

As a staff officer Sucre gained a reputation for organization, preparation and extensive knowledge of artillery and fortifications. He later served on Mariño’s staff and commanded a regiment of engineers.

In 1813 Sucre and 90 others left their discourteous hosts on Trinidad, retrieved a cache of weapons, crossed the Bocas del Dragón strait to their homeland and seized the port of Güiria. Several successful engagements followed, and the 1813 campaign under Mariño ultimately liberated three Venezuelan provinces. Bolívar entered Caracas that August and declared the republic restored. The following year Mariño defeated the royalists at Bocachica, a fight in which Sucre was mentioned in dispatches.

Despite a brilliant follow-up victory at the second battle of La Victoria, the year 1814 proved disastrous for Bolívar and his cause. Suffering a series of defeats, he withdrew first to Caracas and then farther east. Sucre covered the retreat with rearguard actions.

Sucre was especially crushed by events in hometown Cumaná, where royalists defeated republican defenders. In the chaos that followed, his stepmother jumped to her death from a window to escape rampaging royalist soldiers, one of Sucre’s brothers was murdered in a hospital, and a feverish sister reportedly died of fright.

In December royalist forces completely destroyed the revolutionary army at La Puerta, forcing Bolívar’s retreat to Caracas. Sucre, for his part, wisely fled to the coastal island of Margarita.

In mid-1815 the Venezuelan revolutionaries made their way to Cartagena, Colombia, where officials warmly received them and sought their help to defend the city from a royalist siege. Sucre was put in charge of the fortifications and artillery. Though the royalists ultimately prevailed, the siege of Cartagena was a testament to the defenders’ courage, fortitude and endurance.

When conditions became intolerable, some 600 of the defenders and their families evacuated the city under fire in small ships. Unfortunately for Sucre and his companions, a storm scattered the small fleet, and those vessels not immediately sunk were decimated by the enemy and privateers. An impoverished Sucre was left with little more than the clothes on his back.

He found himself first in Haiti, then back on Trinidad by 1816. When Bolívar returned to Venezuela, Sucre and others pooled their resources to purchase a small boat for their own return. Yet again the weather was against them, and the boat wrecked in a storm. Sucre spent the night afloat, holding onto a box. Undeterred, he made his way to Mariño, who gave him command of a battalion and later made him chief of staff.

By 1817 Bolívar and his followers had re-established the Republic of Venezuela and formed a provisional government. Surprisingly, the revolutionaries gave supreme command of the army to Mariño rather than Bolívar. At the time Sucre commanded a division in cooperation with Gen. Rafael Urdaneta. When the latter objected to Mariño’s elevation to command and committed his troops to Bolívar’s service, Sucre and his division followed. Bolívar rewarded Sucre by appointing him commander of the Lower Orinoco department and later chief of staff to Gen. José Francisco Bermúdez, commander of the Army of the East.

Sucre proved himself an excellent field officer. He particularly excelled at campaign preparation and logistics, including munitions, provisions and medical resources. His ability to plan carefully and anticipate difficulties stabilized the successes of the rash Bermúdez. Sucre’s calm temperament also made him a useful intermediary when disagreements arose between Bolívar and his generals. For example, when Bolívar ordered Mariño’s arrest for insubordination, Sucre brokered a compromise that allowed Mariño to eventually return to honorable service.

In 1820 newly promoted Brig. Gen. Sucre was appointed to Bolívar’s staff. The already deep bond between the pair grew stronger as Bolívar delegated ever greater authority to his protégé. Sucre, for his part, found in Bolívar a father figure, whom he treated, as historian Quintero-Aldama puts it, “with affectionate familiarity, like the son who reserves his intimate love for the author of his days.”

Sucre reportedly admired Bolívar’s courage, while the latter admired Sucre’s budding leadership abilities. Sucre was absolutely loyal to Bolívar and his ideals, and the young general soon justified his commander’s trust in him amid fighting on the slopes of an Ecuadoran volcano named Pichincha, overlooking Quito.

Bolívar had long dreamed of creating a unified nation he referred to as Gran Colombia. Following his June 24, 1821, victory at Carabobo and the subsequent liberation of Cartagena, Gran Colombia became a reality, comprising present-day Venezuela and Colombia. Bolívar sent Sucre with a force of 2,000 men to seize the Ecuadoran province of Guayaquil, including Quito, for the new republic.

Sucre set out for interior Guayaquil in January 1822, intent on driving out the Spaniards. A month later, after seizing the city of Cuenca and severing enemy communications, he marched north on Quito, planning to link up with Bolívar, then leading a column south from Pasto, Colombia. The latter met such stiff resistance from royalist forces, however, he was unable to continue his march.

As Sucre moved to cut off the road to Pasto, the Spaniards withdrew inside Quito. Rather than mounting a costly head-on charge against the royalist defenses, the general ordered his troops to climb Pichincha at night in order to fire on the enemy from higher ground.

At dawn on May 24 the Spaniards spotted the flanking maneuver and moved to attack. Just as it appeared the royalists might prevail, Sucre ordered a bayonet charge that turned the momentum in favor of the revolutionaries, who drove the Spaniards from the mountain. The enemy retreated into Quito and surrendered the next day. The victory added much of present-day Ecuador to Bolívar’s Gran Colombia. It also established Sucre’s reputation as a brilliant tactician.

Following his success Sucre was promoted to major general and assumed command of the 9,000-man republican army, with Bolívar serving as supreme commander. On Aug. 6, 1824, while chasing down royalist holdouts amid the Peruvian War of Independence, the pair directed a 1,000-man cavalry troop against a Spanish force of comparable size on the marshy plain of Lake Junín, in the highlands east of Lima. The Spaniards seized the early initiative, but Bolívar’s presence inspired his men to rally and rout the enemy horsemen.

When the Spaniards broke, Sucre pursued them relentlessly. It has been said the Spanish lost more men during the retreat than in the fight. The battle again highlighted Sucre’s campaign planning and leadership abilities. Only 29 at the time, he’d commanded a diverse force of Colombians, Argentineans, Peruvians and European volunteers. The victory led to the incorporation of several Peruvian provinces, including Cuzco and Lima, into Gran Colombia.

In a grand gesture of trust, Bolívar gave command of the army to Sucre for the remainder of the South American campaign. That trust was validated at the decisive battle of Ayacucho.

In November 1824 the royalist army under Gen. José de la Serna, the Spanish viceroy of Peru, maneuvered into position to surprise and ambush Sucre’s column. Anticipating the maneuver, Sucre slipped the trap and dispersed onto the plain of Ayacucho.

On December 9 Sucre positioned his troops for battle. Gen. José de la Mar’s division held the left, while Gen. José María Córdova’s division anchored the right. Directing the cavalry in the center was English-born Gen. William Miller. Gen. Jacinto Lara held a division in reserve. In all Sucre fielded just shy of 6,000 men and a single cannon vs. the Spaniards’ 9,000 men and 14 cannons.

From the high ground the Spanish attacked Sucre’s left and center with two divisions. Sucre met them with infantry and two regiments of cavalry, which managed to halt the enemy advance. De la Mar’s division fell back due to heavy musket fire from a royalist division that descended the heights. A Colombian battalion also fell back. It appeared the republican army was about to collapse. At that moment Miller led a cavalry charge that rallied de la Mar’s men and halted the royalists. Sucre then ordered Córdova to launch a do-or-die charge across the plains of Ayacucho. The maneuver broke the royalist army.

The battle had lasted an hour, and the republican victory was complete. The royalists had suffered 1,800 dead and 700 wounded and lost all their artillery. Some 600 officers—including the viceroy—were captured, as were nearly 3,000 enlisted troops. The republicans lost 370 killed and 609 wounded. The stunning victory effectively ended Spanish rule in Latin America.

Bolívar was overjoyed. “The battle of Ayacucho is the summit of American glory, and it is the work of Gen.Sucre,” he wrote. “[He] is the hero of Ayacucho. He is the redeemer of the children of the Sun. He has broken the chains with which [conquistador Francisco] Pizarro bound the empire of the Incas. Posterity will see Sucre standing over Pichincha and Potosí, carrying in his hands the cradle of Manco-Capac, the chains of Peru broken by his sword.”

Bolívar rewarded Sucre with a new rank—Gran Mariscal [Grand Marshal] de Ayacucho.

Despite his young marshal’s decisive victory at Ayacucho, however, nothing could prevent the eventual decay of Bolívar’s dream of South American unity. Stricken with tuberculosis, the Liberator expended much energy in continual disputes with jealous politicians. Previously loyal regiments and battalions rebelled, and Bolívar was even accused of having betrayed his own republican cause. He came to see Sucre as the only general he could trust. In 1825, in a demonstration of that trust, he deferred to Sucre as Bolivia’s president, though the people had wanted their nation’s namesake to lead them.

Perhaps predictably, things did not go well for Sucre in office. Political elites—notably wealthy and well-connected oligarchs—resisted his economic reforms, which included the systematization and centralization of tax revenues. Rivals plotted against him. Sucre resigned in frustration and withdrew to private life in Quito.

Meanwhile, Bolívar’s Gran Colombia was splitting asunder, the Liberator himself barely escaping a Sept. 25, 1828, assassination attempt. Sucre kept in contact, but only through letters. All that changed in 1829 when Bolívar implored his marshal to defend Gran Colombia against an increasingly belligerent Republic of Peru. Thus the ever loyal Sucre found himself opposite his old comrade in arms, Marshal José de la Mar, the president of Peru. A native of Ecuador, de la Mar was attempting to annex its southern provinces to Peru. The armies met at Portete de Tarqui on February 27.

Many of the respective officers had fought as comrades at Ayacucho and other battles of the revolution. Sucre hoped for a peaceful resolution, but when that proved impossible, he went into battle with his usual determination. The fight lasted about a half hour and ended in the defeat of the Peruvian army, which lost upward of 1,300 killed, wounded or captured. Sucre’s victory kept the Ecuadoran provinces intact, laying the groundwork for that nation’s future autonomy. Peru and Gran Colombia signed a treaty that September and later established a permanent border.

Bolívar then persuaded Sucre to return to Bogotá to preside over a government in turmoil. When Sucre failed to prevent Venezuela from seceding from Gran Colombia, he resigned and set out to rejoin his wife and toddler daughter in Quito.

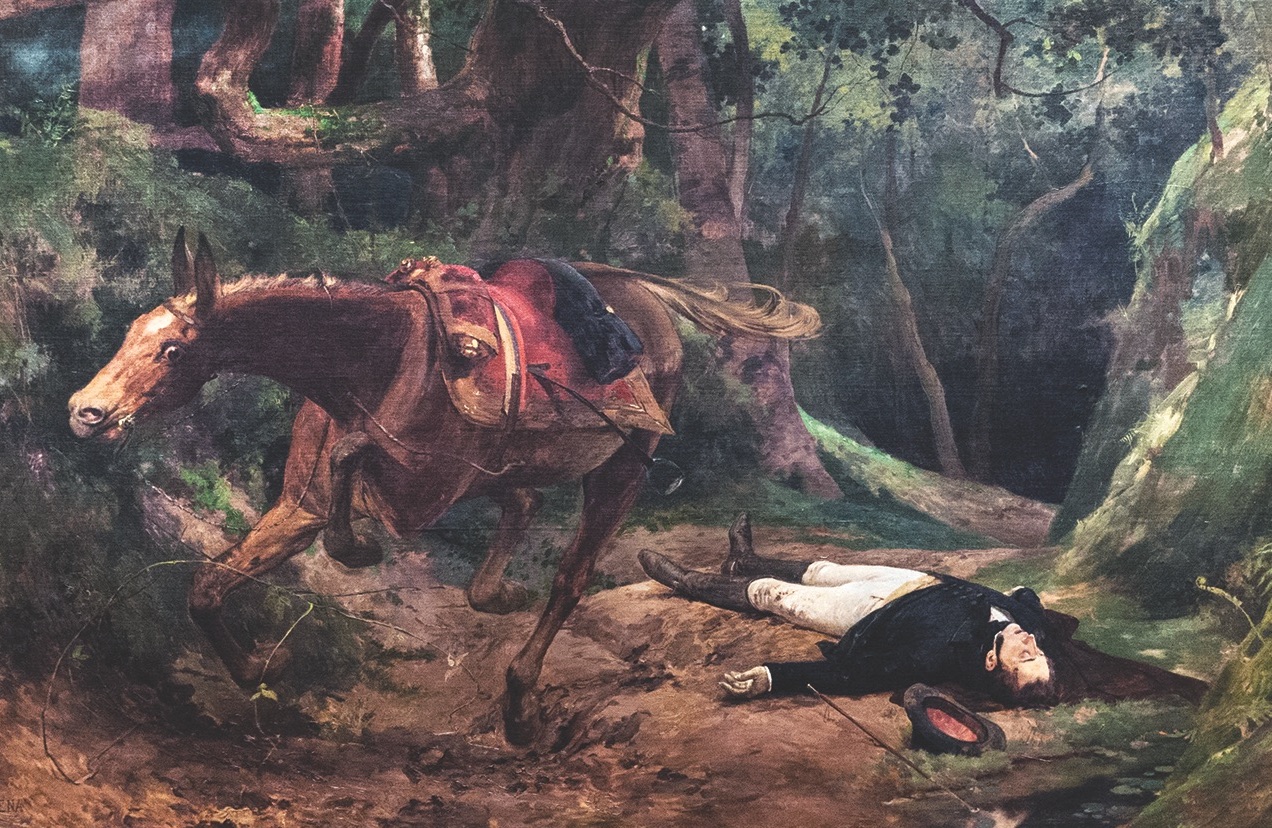

He never reached them, for on June 4, 1830, ex-royalist gunmen ambushed and murdered Sucre near Pasto. He was just 35. His remains were eventually interred in Quito’s Metropolitan Cathedral.

There is no doubt Sucre had many powerful enemies, and his death has since become the subject of numerous conspiracy theories. Among the most pernicious is that Bolívar himself wanted Sucre out of the way. It is unlikely, however, he orchestrated his friend’s death. Indeed, when Bolívar heard of Sucre’s death, he was reportedly apoplectic with grief. “It is impossible to live in a country,” he wrote to another former comrade, “where they cruelly and barbarously assassinate the most illustrious of generals whose merit has produced liberty in America.”

Sucre never wavered in his devotion to Bolívar. “It is not your power but your friendship that has inspired my most tender affection for you,” he wrote not long before his murder. “I will keep it, whatever the luck that befalls us.” Bolívar died barely six months after Sucre’s assassination. Gran Colombia dissolved the following year.

It is difficult to overstate Sucre’s impact on South America. He played a key role in four victories that led directly to the independence of those nations involved. Certainly without his resolute young marshal Bolívar would not have become the revered Liberator of the Spanish American wars of independence. MH

Jerome Long is a former military history instructor at the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, Kan. For further reading he recommends Antonio José de Sucre (Gran Mariscal de Ayacucho): Hero and Martyr of Independence, by Guillermo Antonio Sherwell, and the monograph “Bolívar and Sucre: Two Men and an American Homeland,” by Nestor Alexander Quintero-Aldama, available online.

This article appeared in the September 2020 issue of Military History magazine. For more stories, subscribe here and visit us on Facebook: