For more than a decade, William “Griff” Griffing has been transcribing letters of Civil War soldiers. It’s not just a hobby, but a passion. He has transcribed thousands of letters and diaries, many held in private collections, which he posts on his Facebook page and website “Spared and Shared.” We asked Griff to share with us some of his most favored, memorable, or compelling letters to date. Check out our Autumn 2022 issue of Civil War Times for the first selection, including a letter from a soldier recounting his experiences at the Battle of Shiloh; a civilian who survived William Quantrill’s grisly raid of Lawrence, Kan., in August 1863; and one from an officer of a USCT regiment recounting the Black troops’ terrifying struggle at the Battle of Brice’s Cross Roads on June 10, 1864.

Here are three more of his selections:

Charles L. Fox

This letter was written by Charles L. Fox of the 8th Indiana Light Artillery. He wrote the letter in October 1863 following the Battle of Chickamauga, sharing a riveting and detailed account of the battery’s action during the engagement. He attributes his survival from a bullet directed at him only because it first ripped through his Bible before slamming into and destroying the beloved picture of his fiancée.

[Note: This letter is from the personal collection of Jim Doncaster and is published with his express consent.]

Chattanooga, Tennessee

October 15th 1863

Dear Sister,

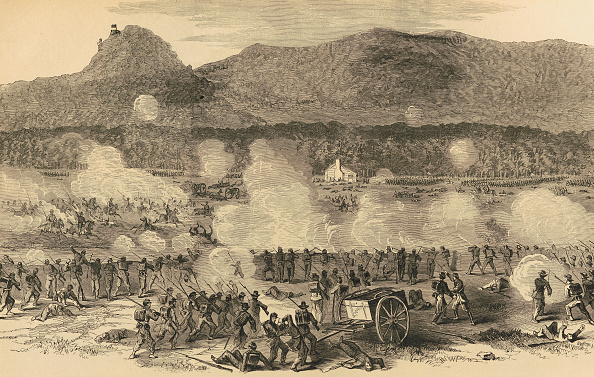

After waiting a long time in hopes of hearing from you, I now attempt to write you another, thinking perhaps that my other epistle may have been mislaid or miscarried. I am well and hope this will find you the same with no apprehension on my account for no doubt you have heard of the two days battles on the Chickamauga Creek which I was in and took quite an active part, having been so closely engaged as to lose our entire Battery with the exception of 1 limber and two caissons. I thought that Stone River was warm work, but that was play compared with the two days fighting on the Chickamauga or deadman’s river. I presume it is useless to give you the details of the fight in general, but shall speak only of our Battery and myself, my losses, and my narrow escape, and what saved me. Well I cannot say with some others that I came off without a scratch for I did not.

I shall not try to describe our position for anyone not acquainted with the mode of forming a line of battle, it would be rather difficult to understand. It is enough to say that we were called from the left center of our army to support our left wing on Saturday morning about ten o’clock of the 20th of September where we had been in position on the bank of the Chickamauga River for three or four days, occasionally shelling the Rebs as they chose to show themselves. But the rascals seeing that we were prepared for them all along our line moved to their right (our left) and there concentrated all their faces knowing that was their only hope with the forces they then had. They had it well planned, but as the old saying is that the best laid plans of men and mice sometimes fail, so it was in this case; for their plan—or rather Gen. Bragg’s—was to get reinforcements from Richmond and draw in all his scattered forces in Mississippi and Alabama, Western Virginia, and then with one mighty blow sweep Rosy [Rosecrans] and his army from the soil of East Tennessee and again come in possession of their saltpetre works and coal mines and salt works, Chattanooga and all, and even to go so far as to take the little city of Murfreesboro which we laid and fortified for six months just for the benefit of such fellows.

But Rosy was as contrary as a hog to drive although they did out number us four to one. Well, they—after moving from the left of center to the left wing on Saturday—were kind and condescending enough to leave us one gun and all the caissons. That gun was No. 3—the one on which I belong. But that evening some of the boys in the infantry not liking for them to have them, charged on the Rebs and took them [back] again. So we came out as we went in excepting one man killed and several wounded and missing.

But now, my losses. In that day’s fight, I lost one overcoat which I miss very much—especially in this wet weather. My knapsack with my portfolio in which were all my letters, and my letters from my Dulcinea, and paper and stamps, envelopes, &c. to the amount of $2.00, but your picture I carried in my watch pocket in my pants. [I also lost] my knapsack [that] contained all my clothes, therefore leaving me without any clothes except what I had on my back and cold, frosty night at that. We slept as best we could on Saturday night and on Sunday morn about ten o’clock in the morning we were called out but it was so still and calm. Not a random shot broke the awful stillness which led us all to think that the Rebs were in favor of observing the Sabbath as well as Rosy who gave orders not to bring on an engagement unless attacked.

But suddenly the storm of war broke upon us and for a moment you would think that all of Heaven’s artillery were turned loose. On they came like a line of demons, yelling like fiends incarnate. Still they were massed on their left. They came column after column, line after line, and our gallant soldiers stood, but not long, for no man or set of men exposed to the fire of ten times their number at this particular point could withstand that terrific fire long unless he were something more than human. But on they came. Our men turned and run and we were ordered to retreat and did so. One gun run into a tree and the horses being shot down, the drivers were ordered to save themselves which they [were] glad to have an opportunity to do.

When we were ordered back, we were told to take a position on a hill [Horseshoe Ridge] just across the [Dyer Farm] cornfield which we were then crossing. And the infantry had the same orders but they were not inclined to do so and when we arrived at the top, not an infantry man was to be seen, so of course there was no support for our Battery. Here we unlimbered and commenced firing and when we would mow down their ranks, they were quickly filled up with free troops for Bragg had been receiving reinforcements since Saturday noon. They then halted in their center and threw round their right and left and on our right they flanked us, or in other words, came round so that they could fire across the length of the Battery, the regiments on our right having run and left us to the mercy of a cross fire. Well I was lying on my face after putting a load in the gun, waiting for No. 4 to fire it off when a minié came whistling along and went in on my left side, just above my waistband and through my blouse jacket, tearing a Testament all to pieces and completely riddling my pocket with holes—and worst of all, breaking my intended’s portrait into a thousand pieces. All I ever saw afterwards was a small piece of the matting. But I still have a small one although [not] so good a picture as the other. The picture was an ambrotype and the glass flew in my hand in many small pieces and that accounts for the scratch I received.

I think in all probability that the picture saved my life as it was next to me, the testament being on the outside. The ball passed through and into the opposite wheel where it lodged. But our horses being shot down—the most of them—we had orders to get what horses were not killed and get out of there, which we did. Out of three we attempted to cut out of the harness, we got one—the other two being shot down while loosening them. As we had no guns and nothing else to fight with, we came back to Chattanooga that night where we are at present in the Artillery Reserve ¹ and likely to be here some time where we are waiting patiently to hear from all our friends and relations. So please write soon and excuse mistakes and bad writing for I am out of practice. If it is not asking too much, I should like your photograph and your intended’s or maybe husband’s before this time. So no more at present. Goodbye.

William Beynon Phillips

This next letter is from a collection of letters written by William Beynon Phillips (2nd Pennsylvania Provisional 2nd Heavy Artillery) and is now in the hands of a descendant named Greg Taylor. Greg approached me many years ago to transcribe these letters and they are among the first that I published. What is most intriguing to me about these letters is that William was a native of Wales and it remains a wonderment to me that foreigners were so willing to step into the ranks and risk their lives for their adopted country. Though foreign-born soldiers are estimated to have made up a quarter to a third of the Union army, I have found them under-represented in the letters I have transcribed so William’s letters are something out of the ordinary.

William’s letters are on their own website: “My Eyes Saw All—in Red & Flame” which can be found on the website.

This particular letter was written in July 1864 from their encampment near Petersburg. Though William had been in the service for some time by this point in the war, most of the time had been spent garrisoning the Washington, D. C. forts and it wasn’t until 1864 when General Ulysses S. Grant gathered up these veteran artillerists and made infantrymen of them that they became battle tested. Because William was a gifted writer, he was selected to serve as the adjutant and was a personal favorite of Colonel August A. Gibson, who at one time commanded the regiment. William writes with a sense of humor and candor.

In this letter, he reflects on the attack made by his regiment on June 17, 1864, in the opening phase of the Petersburg Siege.

[Note: This letter is from the personal collection of Greg Taylor and is published with his express consent.]

Headquarters, Provisional 2nd Pennsylvania Heavy Artillery

2nd Brigade, 1st Division, 9th Army Corps

Near Petersburg, Virginia

Fourth of July, 1864 (Evening)

Dear Annie,

I am exceedingly happy to answer your letter (or wee note) received yesterday. I would scold you for such a puny thing as that was, but, that you were so kind as to put some trouble on something which I prize very highly, and am very, very thankful indeed.

Now my dear, what shall I say? I say that another Fourth is about receding into that eternity, which many of us poor fellows are threatened with, spent, I need not add in not the most agreeable manner, cooped up, and not dare stand up to straighten a stiffened limb without getting a reminder from those fellows over the field, who are very careless in firing their pieces, they may hit a fellow. The only agreeable feature in the day is that we have all day been expecting “to move on the enemy’s works” or at least a lively artillery duel. But I am disappointed even in this. Everything and everyone has been quieter than I have experienced in the campaign. [There is] nothing to be heard but the sharpshooters who, like the wicked, are never at rest. A plague on them.

We had a big treat today. Somebody sent us a barrel of onions and about 200 pickles. The boys have a breath this evening more strong than sweet. If the “ Johnnies ” ever attempt a break tonight, I half believe they’ll be driven back by the rather strong odor of onions.

Since I wrote you last, nothing has transpired in Army matters – only that from there we have advanced some 900 yards. I hardly like this monotonous business of besieging. There is not enough excitement to counterbalance the danger. But I must grin and bear it, take a smoke, and build castles in the air. It’s no use, you know, to despond, but to hope on, hope ever, and make calculations for some good old time I am going to have next winter.

I believe I am a lucky youth. I suppose – if you only saw what the Rebs have thrown at me for the last 60 days – you would think so too. But on that awful 17th [of] June, [the battlefield] was the hottest place yet. I was so excited, that I knew nothing of the danger. My eyes saw all, in red and flame, but I could not digest it somehow. [The] only thing I knew I was rushing [forward], half carried on by some other power than myself, until I tumbled head and heels in the rebel works, to see the “Johnnies” put through the woods beyond. But I didn’t stay there long, for they rallied and drove us out. But the next time we made them leave, and stay at a respectable distance of some 1000 yards. My eyes saw all, in red and flame, but I could not digest it somehow.

Fighting is a serious business, Annie. It’s no use for any one to say that he cares nothing for a battle. I do. I don’t like it. But when I am ordered into it, I go. And after getting up my pride a little, I manage to stand up to the scratch as good as anyone – I mean that – when I have to run up on a charge, right in teeth of their batteries. I don’t care half as much when the rebels attack us. Then by George, the shoe pinches on the other foot. My stock in trade to do this business is about an ounce of courage and the balance in pride and honor. With that, I manage to put on a bold face and give the Rebs a dusting now and then.

Now I suppose you will find a good many errors in this letter. Excuse them, my dear, if you please. Those confounded sharpshooters have a particular spike on my headquarters, and the dust flies all over from their shots, fired onto my embankments. That, you know, is not very pleasant. Then those abominable mortars – they are opening again and, from the fact of our lines of battle being between the Rebel Artillery and our own, and both sides working their guns to silence the other, we are in a nice fix.

I am going to get out of this business next winter, as soon as the campaign is over. I believe I can find something more agreeable, where the idea of getting cut up into nobody knows what is not entertained. My love to Sue, and tell her I am expecting a letter from her. There goes another. Phiz, bang.

Write soon. Write often. Love to all. Now I am done.

Goodbye, Good night. My best affection and love,

Yours & Yours, Amen — William

Enoch C. Dow

This last letter is written by Enoch C. Dow of the 19th Maine Infantry. In the letter, datelined from “Camp near Falmouth, Va.,” Enoch describes the opening phase of the Battle of Chancellorsville which got off to a splendid start. He attributes the early success to the decision to noiselessly carry the pontoon boats to the Rappahannock river instead of hauling them by wagon—a little known fact that is often overlooked in history books.

[This pension file letter was collected by Charles T. Joyce.]

Camp near Falmouth, Va.

Wednesday, April 29th 1863

Sister Nellie [Ellen (Dow) Harriman],

As I have not written to you for some time, I thought I would just drop a few lines this evening informing you that we are all well. Also that the whole army is on the move excepting our division which is doing picket duty at the present time. We shall not be likely to advance until the picket line is broken up which will not be until our folks get across the river and give them battle. Our troops seem to be moving up to the right mostly to cross at some point there. I understood that our cavalry crossed at Kelly’s Ford yesterday and the report today is that they have got in the rear of the enemy and are doing finely. If that is the case, I think we will show them what yankees can do between now and next Saturday night.

The battle has already begun although not much has been done at yet towards it. There was a little fighting at Kelly’s Ford yesterday and some more this morning whilst our troops were crossing here at the centre but they didn’t make much out of it for they hardly knew that our men were coming before they were over the river. The way they surprised them was by the men carrying the pontoon boats down to the river instead of hauling them as they usually do—not making but a little noise in the operation (and it being foggy and dark). ² They got their boats into the river before the rebel pickets knew or discovered what they were up to. They tried terrible hard to get into their rifle pits but the damned yankees—as they call them—threw the shells into their ranks so fast that they couldn’t come it so they broke and run like sheep for some old building where they could get out of sight. I believe there was only two wounded during the skirmish of our men but I reckon they had a few dead ones to bury by the appearance of things.

There is some fifteen thousand infantry and a number of batteries across here at the centre and it looks like there would be warm work tomorrow if not before. But the battle will be over and the victory decided by the time you receive this without doubt. There is many a poor fellow soldier that never will see the sun sink behind the horizon again. I may be one of that number. However, we will not think of that but trust to greater power.

Tell Father that we were paid off yesterday four months pay so there will be $32.00 I received at the town treasure for him to collect.

Excuse this for it was done in a hurry. And tell somebody to write if they know how for I haven’t received but one letter from home for three weeks. Write as soon as you can. Goodbye until I write again, Nellie.

—Sergt. E. C. Dow