The annual Reno Air Races usually evoke images of the Unlimited class: highly modified warbirds competing around a roughly eight-mile oval course at speeds approaching 500 mph. The smaller and slower Formula One class, however, has attracted more pilots and aircraft in a half-century of racing than the other five Reno classes. Often called the “Builder’s Class” because nearly all entrants build their own airplanes from scratch or modify homebuilt designs, the class requires the use of a Continental O-200 or equivalent 200-cubic-inch engine, in addition to a minimum wing area of 66 square feet and minimum empty weight of 500 pounds. Even with a course only a bit longer than three miles, Formula One racers manage to achieve speeds of 250 mph.

After World War I, military surplus aircraft initially dominated air racing in the United States and abroad. In 1924, however, organizers of the National Air Races in Dayton, Ohio, featured two events restricted to light airplanes with engines of less than 80 cubic inches, i.e., 18- to 20-hp motorcycle engines. Initial results were disappointing: Only six of nine registered contestants arrived for the races, and all six had engine difficulties. Aviation magazine noted, “Engines which run smoothly and continuously when installed in motorcycle frames refuse to give even one minute of non-stop operation in a fuselage.” Only three entrants completed the speed race, and several pilots failed to get airborne for the speed and efficiency race, including Edward Bayard Heath, who crashed his Feather biplane on takeoff.

The disappointment in 1924 didn’t dampen Heath’s vision of an airplane in every garage. He viewed racing as both a way to earn money and to market his aircraft, and his fortunes changed when he brought a new design, the Tomboy, to Philadelphia in 1926. Heath jumped to an early lead in the speed race for light airplanes, 10 laps over a five-mile course. As the KRA midget monoplane in second place caught up to Heath, its spinner flew off with a bang. The KRA’s pilot broke off and circled once outside the course. Finding no damage other than the lost part, he reentered the race but couldn’t catch Heath, who won with an average speed of 91 mph.

Despite its racing success, the Tomboy wasn’t intended for construction by an amateur homebuilder. Instead, Heath designed a high-wing monoplane with external struts—a configuration that was strong, light and easy to build with hand tools. He took his Parasol, powered by a 23-hp Henderson motorcycle engine, to the National Air Races at Felts Field, in Spokane, Wash., at the end of September 1927.

Heath must have been dismayed when Jack Irwin, a West Coast competitor who offered kits and fully assembled Meteorplanes equipped with 20-hp engines, showed up in Spokane with a special racing biplane he had finished just days earlier. Reporters considered Irwin’s nameless plane, which with a 14-foot wingspan was even smaller than the Parasol, the favorite to win. But Heath’s luck held for both scheduled lightplane races—one consisting of five laps and the other 10—around the six-mile course. The day before the races, Irwin decided to take his new biplane up for some practice, and during the takeoff roll he hit a hole and tore off the right wheel. With no time for repairs, Heath’s only other competitor withdrew, and he won both races uncontested.

Heath took out an ad in Popular Aviation magazine touting his wins, without mentioning his lack of competition. Readers flooded the editor with requests for information on how to build the Parasol, and Heath was happy to oblige, penning monthly articles for seven issues. As more Parasols flew, builders and pilots demanded more speed and better climb performance. That drove Heath to develop his first low-wing design, but on February 1, 1931, he was killed when it crashed during a test flight.

By 1931, state laws and vagaries in federal regulations began putting homebuilders out of business. By the mid-1930s, homebuilding had been largely driven underground, except for those who took advantage of loopholes that allowed their aircraft to be certified as “experimental” and used only for airshows or racing.

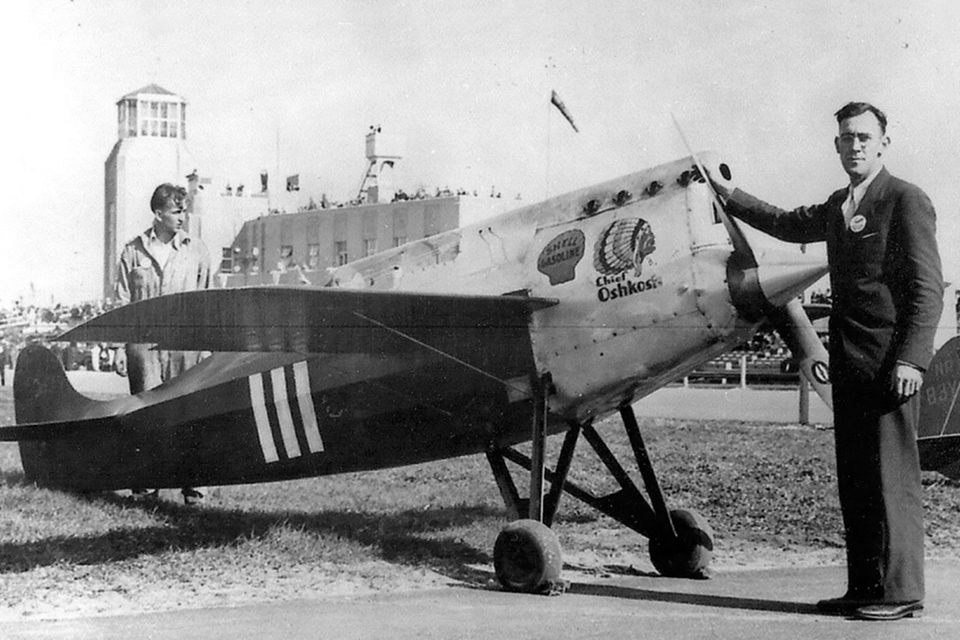

Midwesterner Steve Wittman, despite being nearly blind in one eye, took advantage of the loopholes and began racing homebuilts in 1931. He had competed in various production aircraft since 1926, but in 1931 he brought Chief Oshkosh—an odd-looking airplane he designed and built himself—to the air races in Cleveland. Chief Oshkosh, named after the Wisconsin town where Wittman lived, had a spindly landing gear, tiny wheels, no brakes and was painted red with a large Indian head on the nose. Racing in the 400-cubic-inch class, Chief could hardly be called a midget, but after the aircraft crashed in 1938 during a race at Oakland, Wittman reassembled the remains into a midget racer in 1947. Aviation writer Robert McLarren observed, “His ships have all resembled barn doors and box-kite contraptions with no semblance of speed or performance in their appearance,” but Wittman often placed in the top-three finishers. In 1937 he used Chief Oshkosh to set a world speed record of 238 mph for an aircraft weighing less than 500 kilograms over a 100-km course.

The final death knell for the early homebuilt aircraft movement occurred on December 8, 1941, when new federal regulations required all aircraft to be certified under strict airworthiness standards, all but guaranteeing that no amateur-built aircraft would fly for at least the duration of World War II. In October 1945, the Civil Aeronautics Administration issued Safety Regulation Release No. 194, which made special-purpose aircraft used for air racing and exhibition again eligible for experimental-aircraft certificates. Although pilots who wanted to fly homebuilts for pleasure were still out of luck, those interested in racing or airshows began dragging their amateur-built craft out of storage. Pilots who wanted to race didn’t have to wait long: In early 1947, officials of the National Air Races, held in Cleveland over Labor Day weekend, announced a renewed category for lightplanes, with a $25,000 purse.

Air racing historian Don Berliner says that much of the public lost interest in racing after WWII. At least part of the problem was that military surplus aircraft were too fast, requiring large courses that made it difficult to see the warbirds for much of the race. The solution: custom-built midget racers that would stress close competition, low cost and increased safety. The Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company, involved in aviation since producing the first rubber aircraft tires in 1909, agreed to sponsor the new class, and in 1947 the Goodyear Midgets were born. The original midgets used a 190-cubic-inch engine; Continental C-85s, produced after the war in large quantities for popular aircraft such as Cessna 140s, were perfect for the class. The specifications precluded production aircraft from being competitive, and the Builder’s Class was born.

Thirteen Goodyear Midgets of uneven quality—Berliner says some of the aircraft “looked like they had been glued together at the last minute”—arrived in Cleveland in 1947. Steve Wittman brought Buster, the resurrected Chief Oshkosh, and Bill Brennard piloted the tiny airplane to a first-place finish, zipping around the 2.2-mile, 25-lap course at an average speed just shy of 166 mph. The next year, 24 midgets arrived, and Herman “Fish” Salmon won in the Levier Cosmic Wind Minnow, with Wittman and Art Chester in hot pursuit. Wittman placed second in Bonzo, and only four seconds separated the third-place Chester in Swee’ Pea II from first-place Salmon.

In 1949 several newcomers attempted to challenge the previous winners, but the event was marred by Bill Odom crashing his war-surplus P-51 into a house, killing himself, a woman and a child. For a decade after the accident, the midgets were the only class of racers flying, and even that was sporadic, with small competitions around the U.S. In 1964, however, racing revived at Reno, and the midgets roared back to life.

Renamed Formula One in 1968, the midget class also upgraded to the standard O-200, a wildly popular engine that could be pulled from a Cessna 150 and mounted on a racer. Although speeds of more than 200 mph had been achieved in the early 1950s, improved propeller technology and aerodynamics pushed speeds higher still—in 1982 aeronautical engineer Jon Sharp achieved 224.5 mph in a race that included retired astronaut Deke Slayton.

But a hidden bomb kept haunting the midgets: the metal propellers that most racers simply pulled from production aircraft. As current Formula One racer Elliot Seguin explains, the propellers are under a lot of stress: A typical propeller on a general aviation aircraft will run at a maximum of about 2,500 rpm, but racers push that maximum to about 4,400 rpm. At those rates, propeller tips can reach transonic speeds, so racers usually shorten the tips, essentially making new propellers and turning race pilots into test pilots. On top of that, Sequin says, “There’s clearly a lifespan thing on the propellers that no one really understands.”

Propeller blades departing aircraft sometimes led to tragic results when the imbalanced propeller ripped an engine from its mount, but others were saved by a rule that requires a backup if the mount fails: a braided cable wrapped around the engine and attached to the airframe. By 1987, metal propellers had caused so many accidents that Formula One racers were required to use “other than metal propellers.” Wood has its own problems with achieving a stiffness equivalent to a metal propeller, so designers began to gravitate toward carbon fiber.

Jon Sharp, who later achieved Formula One fame with Nemesis, first raced with a carbon fiber propeller in 1988, and in 1989 he reached nearly 243 mph in a Boyd Blue Streak during time trials. With better propellers, racers continued to push speeds above 250 mph. The current Formula One race record is held by Steve Senegal, who hit 260.8 mph in 2012 flying Endeavor, an Arnold AR-6. Senegal also holds the Formula One record during a qualifying round, 267.3 mph, set in 2014.

That same year, another major Formula One event occurred: The only maker of composite racing propellers, Twisted Composites, exited the market. The hunt is still on for a new propeller, and racers tried new designs at both the 2015 and 2016 Reno Air Races. But Seguin says the newer propellers are not yet competitive with the Twisted Composites props, so it may take more development before they begin to produce winning results. On the other hand, Seguin says there has been a re-emergence in the Formula One class; the 2016 races saw a full field of 24 aircraft. “Guys are excited and want to try out new things,” he notes. “The propeller is just one corner of the problem that can be worked on.”

The midgets might be smaller, slower and quieter when compared to their flashier brothers in Unlimited racing, but the excitement for fans and dangers to the pilots are every bit as real. For his part, Elliot Seguin is sanguine about such dangers. When asked why he tests many of his aircraft modifications during a race itself, instead of beforehand, most racing pilots would probably agree with his reply: “Every race motor has a fuse of unknown length, and as soon as you start it the first time, you’re lighting that fuse and you don’t know where it’s going to end. So if we spend a bunch of money on a racing motor, I don’t want to blow it up at home, I want to blow it up [at a race] in front my buddies.”

Eileen Bjorkman is a retired U.S. Air Force officer and freelance writer. Her book The Propeller Under the Bed: A Personal History of Homebuilt Aircraft, was published by University of Washington Press in 2017. Further reading: Airplane Racing: A History, 1909-2008, by Don Berliner.

This feature originally appeared in the May 2018 issue of Aviation History. Subscribe today! Read more about the history of air racing in Speed and Spectacle: the 1930s National Air Races, from the May 1999 issue of Aviation History.