In the early morning hours of March 12, 1938, German troops poured across the Austrian border, fulfilling Adolf Hitler’s dream of Anschluss, the incorporation of Austria into the Third Reich. When the German dictator arrived in Vienna two days later, Sigmund Freud was still ensconced in his longtime residence and office at Berggasse 19.

At 81, Freud was the city’s most famous resident, the founder of psychoanalysis, a pioneering field that the Nazis denounced as a Jewish pseudoscience. All of which made him an obvious target for the new rulers. But unlike those fellow Austrian Jews who had emigrated earlier when it was relatively easy to do so, he had stubbornly refused to follow their example.

It would take a concerted effort by a well-connected and devoted group of friends and followers to extricate him from Vienna at nearly the last moment. The fact that they succeeded in getting him to London — where he spent the last 16 months of his life until his death on Sept. 23, 1939, at the beginning of World War II — does not diminish the question of why he was nearly trapped in the Austrian capital in the first place. It also raises the issue of Freud’s views about the politics of his era, including the swirl of events that would produce two world wars.

Should Freud Have Known Better?

In theory, Freud was better positioned than anyone to understand the dark forces at work in Central Europe in the first half of the 20th century. In his famed 1930 essay “Civilization and Its Discontents,” he discussed man’s “aggressive cruelty,” which he said “manifests itself spontaneously and reveals men as savage beasts to whom the thought of sparing their own kind is alien.”

But Freud was no less prone to illusions than many of his contemporaries when it came to the immediate dangers around him. He failed to recognize the gathering storm that would produce World War I, and later underestimated the strength of the Nazi tide that would engulf his native city and most of the rest of the continent, setting the stage for the Holocaust.

Old-School Thinker

Freud was a truly revolutionary thinker in his new field of psychoanalysis, offering brilliant insights into the working of the human mind. But he was also the product of a largely conventional upbringing in Vienna, the capital of the Habsburgs’ multinational Austro-Hungarian empire that was soon to disintegrate. His early personal experiences exposed him to wars and upheavals, but even then, long before the rise of Hitler, he frequently misjudged their scope and implications.

As a young teenager, Freud had followed the Prussian wars that led to the unification of Germany and its victory over France in 1871. His sister Anna remembered how he hung large maps in his room, sticking pins in them to show the movement of the rival armies.

“Every evening I could listen to the conversation between father and son on the state of the war,” she noted.

When a Bosnian Serb nationalist assassinated Austria’s Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie in Sarajevo, Freud — along with so many of his compatriots — initially failed to comprehend the scale of the tragedy that was rapidly unfolding during the summer of 1914. This was a result of his reluctance to admit that his surroundings, and all the associated assumptions about the world he had grown up in, were seriously imperiled.

Staunch Monarchist

According to his son Martin, the entire family accepted the Habsburg monarchy: “We Freud children were all stout loyalists, delighted to hear, or to see, all we could of the Imperial Court.”

He recalled how excited they were whenever they caught sight of a Hofwagen, a court coach: “We could tell with precision the extent of the passenger’s importance by the color of the high wheels and the angle at which the magnificently liveried coachman held his whip.”

As Martin also recalled, his mother, Martha, who was born in Hamburg, never lost her North German accent or “her feelings of patriotic devotion to the Imperial German family.” Since Austria-Hungary was Germany’s ally, there was no problem reconciling Sigmund’s and Martha’s loyalties.

After the assassination in Sarajevo, events quickly spiraled out of control. On July 23, Austria, with the backing of Germany’s Kaiser Wilhelm II, issued an ultimatum to Serbia, including demands for the suppression of “subversive” elements that “constitute a standing menace to the peace of the Monarchy,” knowing that the Serbian government would reject them.

Yet, on July 26, Freud wrote to his partner Karl Abraham, a leading German psychoanalyst, expressing his support for this action.

“Perhaps for the first time in 30 years I feel myself an Austrian, and would like just once more to give this unpromising empire a chance,” he said. He optimistically added: “Should the war remain localized to the Balkans it won’t be too bad.”

War Comes to Freud’s Doorstep

On July 28, Austria declared war on Serbia. The next day, Freud asserted to his brother Alexander, “I believe that no great power will bring about a general war.”

Two days later, German troops invaded Belgium and then moved on to France, where they battled French and British troops. The Central Powers — Germany and Austria-Hungary — were soon joined by Turkey and Bulgaria, facing off in a widening war against the Triple Entente of Britain, France and Russia. Italy proclaimed itself neutral at the outset of hostilities but declared war on Austria-Hungary in 1915. This was the “general war” that Freud had claimed would be avoided.

Nonetheless, Freud was buoyed by the initial military successes of Germany and Austria, rekindling the sense that there was unity in the German-speaking world. In September, he traveled to Hamburg to see his daughter Sophie, who had given birth to his first grandson. In a letter to Abraham, he explained that he had visited the city before, but for the first time it did not feel “as though I were in a foreign city.”

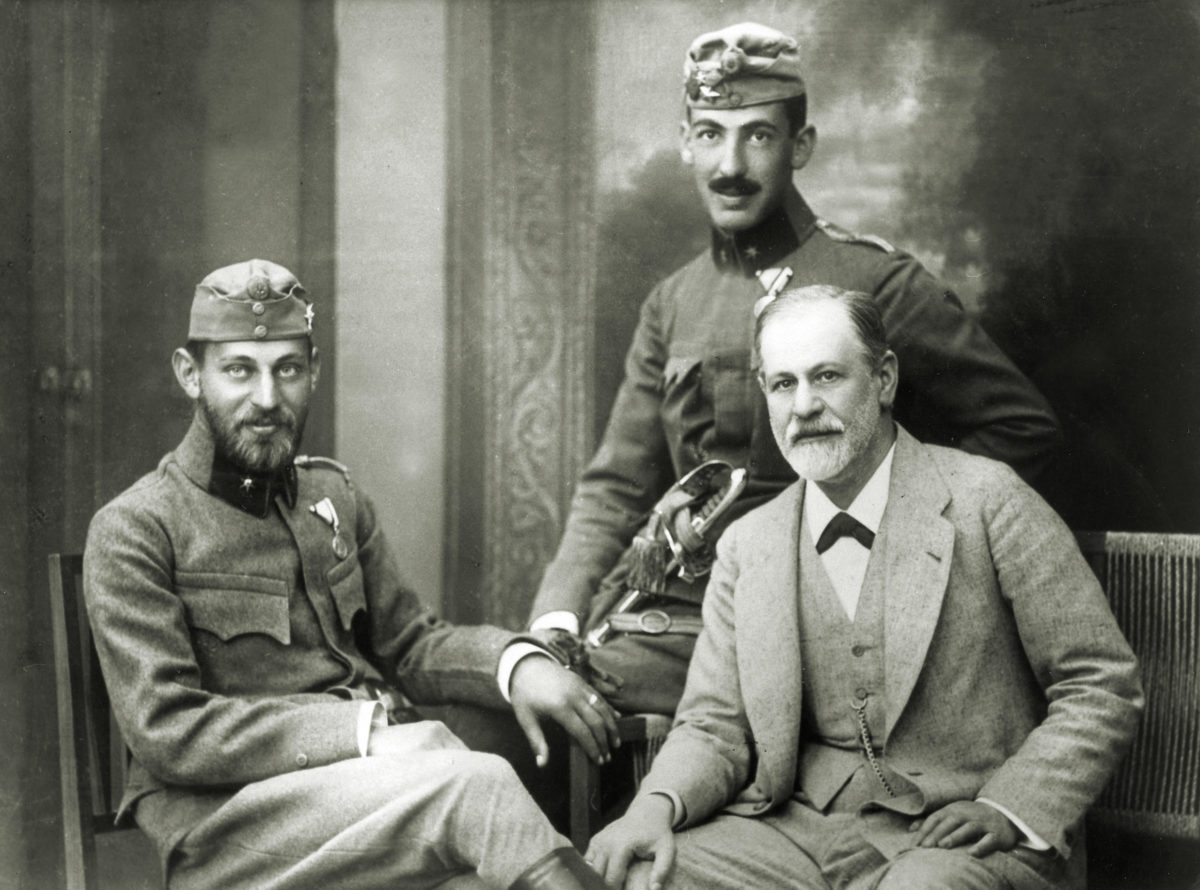

The Fighting Freuds

Freud was inclined to believe the early optimistic predictions of victory by the Austrian and German authorities, although he wasn’t eager to see his sons enlist. But Martin, the eldest, had served a few months in the Imperial Horse Artillery in 1910-11 until he broke a leg in a skiing accident, and he quickly volunteered to return to duty when the war started. His old regiment took him back as a junior officer.

Freud approved, but understandably worried about his safety. In a letter dated Dec. 20, 1914, he urged Martin not to take unnecessary risks.

“I still think you regard the war as a kind of sporting excursion,” he wrote, adding that he and Martha would be spending a “sad and quiet” Christmas. (Like many secular Jews, he treated that Christian holiday as a normal time for family gatherings.)

Martin noted that his father’s letters were “severely practical,” lacking in any expressions of sentiment. Still, they conveyed his concern.

Freud’s worries about Martin were accentuated by his knowledge that his son still clung to romantic notions of warfare. Martin’s wartime experiences, which differed dramatically from those of millions of other soldiers bogged down in murderous trench warfare, did little to change his outlook.

“The truth is I was then enjoying the happiest time of my life,” Martin Freud recalled in his autobiography.

During the Austrian victories in early 1915, Martin rode on horseback patrol on “a magnificent chestnut,” seemingly fulfilling a dream from early childhood. In that dream, “I saw myself mounted on a magnificent war charger riding into a freed city to be welcomed with flowers and kisses from the liberated maidens, all very beautiful,” he wrote. “The reality, as it turned out, was even more colorful and the girls more lovely: and I was indeed completely happy.” He fought on both the Russian and Italian fronts, winning seven medals for bravery.

Fortunate Family

The dream could not last forever, and Martin was shot in the thigh in 1918. Shortly before hostilities ceased later that year, he was captured by the British in Italy and ended up in an Italian prisoner-of-war camp for officers. He described himself as “one of the victims of the downfall of an ancient empire,” and he was not released until August 1919. Like his father, he was disappointed by the war’s outcome and his spirits had finally sagged, but he could not complain about his conditions in captivity. He pointed out that he returned to Vienna “somewhat plump as the result of a diet of spaghetti and risotto.”

Freud’s other two sons also served, enlisting a bit later than Martin, and both emerged unscathed. Oliver, the second son, was an engineer assigned to a railway regiment, while Ernst, the youngest son, spent two years on the Italian front before he came down with tuberculosis and a duodenal ulcer, leading to his discharge right before the war ended. Compared to so many other families, the Freuds were extraordinarily lucky.

War of the Psychoanalysts

The war split not only Europe but also the psychoanalytic movement, quite unevenly. With one notable exception, Freud’s top lieutenants were based in cities like Berlin and Budapest, which meant that they, like Freud, were on the side of the Central Powers.

The exception was Ernest Jones, a London-based Welsh physician who was Freud’s most fervent disciple in the English-speaking world. Although direct mail was suspended between the two sides, Jones and Freud managed to keep up their correspondence via friends in neutral countries like Switzerland, Holland, Sweden and, initially, Italy.

The two men were intent on maintaining their friendship and professional partnership, but they approached the war from radically different perspectives. On Aug. 3, 1914, Jones wrote: “We are prejudiced against Germany … Austria is unpopular for getting everyone into trouble, but her attitude toward the Slav people is fairly well understood. No one doubts here, however, that Germany and Austria will be badly defeated, the odds are too much against them.”

At that point, Freud was still confidently expecting victory for his side.

“All my libido is given to Austria-Hungary,” he proclaimed.

He also warned Jones about the perils of believing British propaganda.

“Regardless of what you read in the papers, do not forget that lies are rampant now,” he wrote. “We are not suffering from any restrictions, any epidemics and are in very good spirits.”

Jones replied that he understood that the British accounts were often “greatly exaggerated,” but offered some advice of his own about German disinformation: “In return I ask you to believe that the Bank of England has not been destroyed by bombs, that Egypt and India have not revolted, and that our coasts have not been bombarded by the German fleet.”

Second Thoughts on the First World War

Neither man was swayed by the occasional barbed comments of the other. But it did not take Freud long to begin reexamining his own view of the war, recognizing that its consequences would be devastating for both sides.

“It is a long polar night,” he wrote to Abraham, “and one must wait until the sun rises again.”

In his 1915 twin essays entitled “Thoughts for the Times on War and Death,” Freud expressed his profound disillusionment with the escalating brutality of the war.

“Not only is it more bloody and more destructive than any war of other days, because of the enormously increased perfection of weapons of attack and defense; it is at least as cruel, as embittered, as implacable as any that has preceded it,” he wrote.

The conflict ignored all notions of international law such as the distinction between civilians and combatants or “the prerogatives of the wounded and the medical service,” he added. “It tramples in blind fury on all that comes in its way, as though there was no future and no peace among men after it is over.”

He decried the “almost incredible phenomenon” of “civilized nations” turning against each other “with hate and loathing.” As he noted, “We had expected the great world-dominating nations of white race upon whom the leadership of the world had fallen … to succeed in discovering another way of settling misunderstandings and conflicts of interest.” Instead, the war was cutting “all the common bonds between the contending peoples, and threatens to leave a legacy of embitterment that will make any renewal of those bonds impossible for a long time to come.”

Judged in isolation, such statements look remarkably prophetic, suggesting that Freud was already foreseeing the long-term consequences of the conflict — not in any detail, but at least in broad outline. They also suggest that he was focused on the destructive forces unleashed around him, absorbed in trying to understand the fighting raging across the continent. But that was true only up to a point.

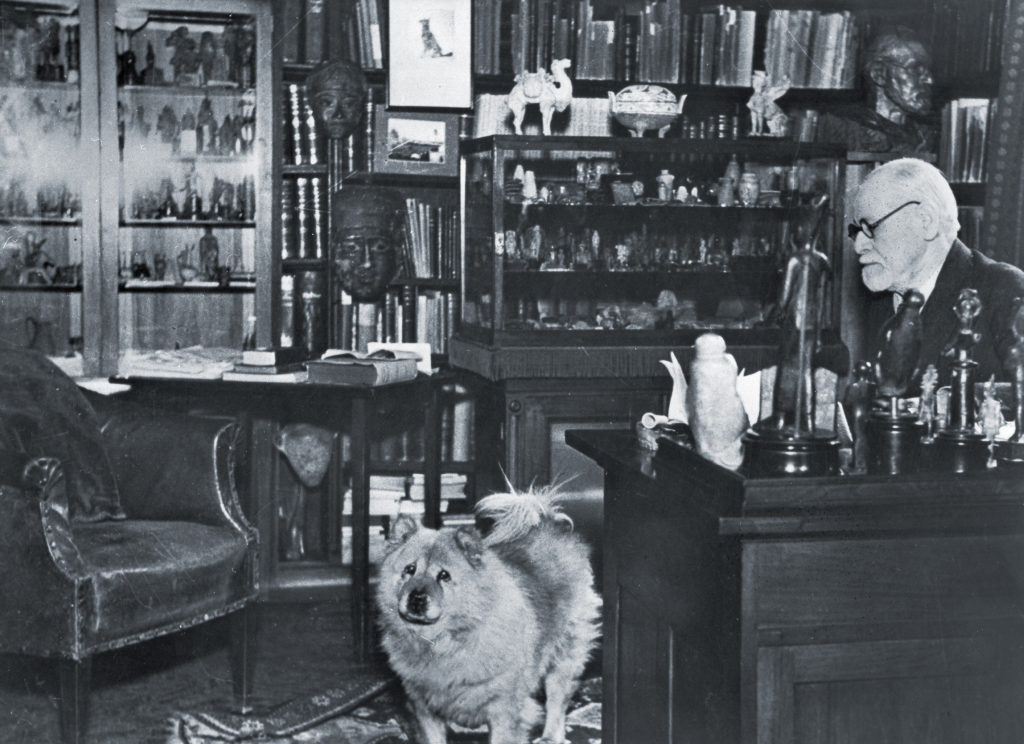

Freud’s One-Track Mind

While Freud could not ignore the cascade of cataclysmic events, he still wanted to keep his head down as much as possible and focus on psychoanalysis, not allowing the war to interrupt them. After a brief suspension, he resumed regular Wednesday evening sessions in his apartment with a small group of close colleagues who discussed their newest findings and techniques, and he delivered lectures on psychoanalysis at the University of Vienna, drawing large audiences. He also continued writing regularly, exploring the variations of neuroses and penning works like “Mourning and Melancholia” that also reflected his mood.

Unlike many of his intellectual contemporaries, Freud did not consider himself to be either a political activist or thinker, and he largely steered clear of involvement in any of the fashionable causes of the postwar period, such as communism. But in 1932, when he received a request from Albert Einstein, whom he had met while visiting Berlin six years earlier, for help with a political project, he made an exception.

The League of Nation’s International Institute of Intellectual Cooperation had asked Einstein to choose another eminent person to exchange ideas with about the “most insistent of all the problems civilization has to face,” as he put it in a letter to Freud. “This is the problem: Is there any way of delivering mankind from the menace of war?”

The Time Sigmund Freud and Albert Einstein Try to Solve War

Einstein was a self-proclaimed pacifist, but he was not trying to enlist Freud in that cause. Instead, he confessed that he had “no insight into the dark places of human will and feeling,” and asked Freud “to bring the light of your far-reaching knowledge of man’s instinctive life to bear upon the problem.”

Einstein added that the most obvious solution was the creation of a “supranational organization competent to render verdicts of incontestable authority and enforce absolute submission to the execution of its verdicts,” something much more powerful than the League of Nations. That would require “the unconditional surrender” by every nation of its sovereignty “in a certain measure.”

But he conceded that “strong psychological factors are at work which paralyze these efforts,” including the ease with which nationalist passions can be turned into “a collective psychosis” that leads to armed conflicts.

Freud was at least as skeptical as Einstein that any institution could succeed in preventing wars.

“Conflicts of interest between man and man are resolved, in principle, by the recourse to violence,” Freud replied. “It is the same in the animal kingdom, from which man cannot claim exclusion.”

New weaponry proved that intelligence was more important than brute force, but the ultimate aim — of eliminating foes in any dispute — remained the same. Most often, this meant killing them, which also “gratifies an instinctive craving,” Freud wrote, but in other cases it could lead to their enslavement: “Here violence finds an outlet not in slaughter but subjugation.”

Like Einstein, Freud observed that “nationalistic ideas, paramount today in every country, operate in quite a contrary direction … there is no likelihood of our being able to suppress humanity’s aggressive tendencies.”

Freud was not only thinking of Hitler’s Nazis, who by then had taken advantage of the popular discontent spurred by the Great Depression to garner the largest number of seats in the Reichstag; he was equally dismissive of the Bolsheviks who “aspire to do away with human aggressiveness by ensuring the satisfaction of material needs and enforcing equality between man and man. To me this hope seems vain,” he wrote. “Meanwhile they busily perfect their armaments, and their hatred of outsiders is not the least of the factors of cohesion among themselves.”

Although he referred to “pacifists like us” who find war intolerable, Freud came across in his letter as less than committed to the pacifist cause.

“All forms of war cannot be indiscriminately condemned,” he declared, so long as almost every nation was preparing “callously to exterminate its rival.” This meant that “all alike must be equipped for war.”

First Thoughts on the Second World War

The same logic should have led Freud to conclude that he had to prepare for the worst as well. When Hitler took power in Germany in January 1933, Freud admitted in a letter to his French colleague Marie Bonaparte, Napoleon’s great-grandniece, that many friends were urging him to emigrate from Austria. While he understood why German Jews were already fleeing, he insisted, “I don’t see any danger here.”

On April 7, he wrote to Jones: “Despite all the newspaper reports of mobs, demonstrations, etc., Vienna is calm, life undisturbed.” While he conceded that the Nazi movement was spreading to Austria, he added that “it is very unlikely that it will present a similar danger as in Germany.”

But Hitler’s ambition to incorporate Austria into the Third Reich was hardly a secret, and Freud was in his movement’s crosshairs as well. On May 10, when the Nazis organized their famed bonfire of the books in a square opposite the University of Berlin, Freud’s volumes were among those flung into the flames. Addressing the aroused mob, an announcer inveighed against the author’s “soul-destroying overestimation of the sex life.”

Freud admitted that “life in Germany had become impossible” for Jews, and he was relieved when two of his sons who had been living there moved to England and France. But he still retained an almost naïve faith that Austria’s rightwing regime could resist a German takeover, even after local Nazis assassinated Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss on July 25, 1934.

When Freud’s youngest daughter, Anna, discussed this period with the American child psychologist Robert Coles decades later, she said that by 1936 it was clear “that nothing would stop Hitler from seizing Austria — or, I should add, Austria from joining Germany,” but the family refused to surrender “to fear and apprehension.”

Why Did Freud Stay in Austria?

So why did the Freuds not leave Vienna then?

“The answer was quite simple: My father was quite sick, he was in pain a lot of the time; he was nearing the end of his life — over 80, with cancer; and he could not imagine any ‘new life’ elsewhere. What he knew was that there were only a few grains of sand left in the clock,” Anna said.

Anna was fully justified in pointing out the dangers of passing judgment with the benefit of hindsight. She was also right to identify her father’s age and health as the overriding concerns for the family. But she may have been guilty of overstatement in her assertion that by 1936 it was clear to Freud that Nazi Germany would swallow up Austria. He was still trying to track increasingly illusory rays of hope, still reluctant to accept the inevitability of such an outcome. As late as Feb. 6, 1938, he wrote to a colleague praising “our brave and in its way decent government” for trying to keep “the Nazis at bay,” although he conceded the outcome was uncertain.

For all of those reasons, Freud was still in Vienna when Hitler engineered the Anschluss two years later. While dispensing a steady stream of penetrating observations about human behavior, he proved to be as fallible as anyone else when it came to making decisions about his own life.

This is an adaptation from Andrew Nagorski’s new book, “Saving Freud: The Rescuers Who Brought Him to Freedom” (Simon and Schuster, 2022).

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.