What I’m proud of is the truth of the show—what happens to the souls of men in war.

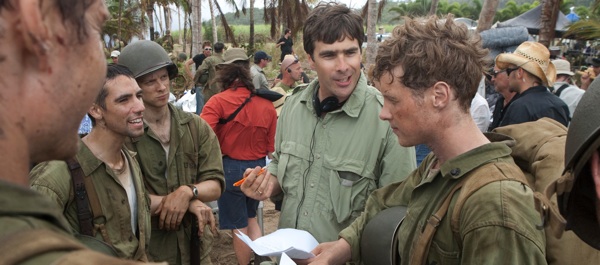

After Bruce C. McKenna wrote part of the HBO Band of Brothers miniseries, his writing career in Hollywood soared. His “Bastogne” episode won a Writers Guild Award and was a finalist for the Hamanitas Prize. In 2003, Steven Spielberg and Tom Hanks hired him to research and oversee the writing of a new epic miniseries, The Pacific, which debuts Sunday, March 14, at 9:00 p.m. Eastern Time on HBO.

Band of Brothers may have opened doors in Hollywood, but McKenna already had an impressive resume. He was the first Western journalist to write about Pamyat, the Russian anti-Semitic movement that emerged after the breakup of the Soviet Union. His work has appeared in The New York Times, The National Review, and Arete. An article he wrote for the National Review led him to write a nonfiction book, The Pena Files, about the extraordinary life of Octavio Pena, the private investigator who has assumed multiple guises to investigate a Mafia empire, corruption in the IRS, and other high-profile cases.

With wife Maureen, McKenna also produced off and off-off Broadway plays. On March 9, he talked with HistoryNet in an exclusive interview about his career and especially his work on The Pacific.

HistoryNet: I have this image of your office. There’s a hat rack in it, and every day you walk in and put on whatever hat you’re going to wear that day—screenwriter, journalist, off-Broadway producer, nonfiction book author. How do you handle the transition from the special demands of one type of creative work to the others you’ve undertaken?

Bruce C. McKenna: It’s all about the story. We all serve a story, whether we’re journalists, screenwriters, producers—you have to have a clear idea of what the story is you have to tell.

Historians and screenwriters are storytellers, we just have different ways to go about it. I’m trained as a historian. I was in the Ph. D. program in Russian Intellectual History at Stanford for year. I had to pick the most arcane thing in the academy, but after a year I realized how arcane this was and that it really wasn’t what I wanted to do. I dropped out of graduate school and became a freelance writer.

I’m a product of all my failures—hopefully, The Pacific isn’t one of them. (Laughs.)

It was great to use my brain that way, but then I have to switch it off and become the storyteller.

HN: Of the 10 episodes of The Pacific, your name appears on seven, four of which you wrote by yourself, including the first two, and three more on which you share credit. What’s it like as a writer to begin telling a story, hand it off to other people, then come back and collaborate with still more people to finish it?

BCM: It’s challenging but also healthy. The structure of the show came out of my head. Steven Spielberg and Tom Hanks hired me to develop this story in 2003. I picked the books that would serve as the basis of the miniseries, picked the men in them who would be represented in the miniseries, picked the stories that would be told.

I also hired all the writers, and I insisted on hiring writers more talented than I am. Robert Schenkkan is a Pulitzer Prize–winning playwright (The Kentucky Cycle). George Pelecanos is an award-winning novelist and was nominated for an Emmy for his writing on The Wire. I couldn’t do it all myself. You have to communicate to them what the story is you want to tell; then, you have to pass it on and trust them.

I talked to all the writers and made sure we all understood the story we were telling. I eventually got a battlefield promotion to co-executive producer to make sure everyone, especially the directors, knew what we were trying to do. Tom Hanks himself did a lot of rewriting on this show. Everyone from the top to very bottom kept an eye on this show to make sure we did what we wanted to do, to get the story right.

HN: You were, of course, part of the team that created HBO’s renowned Band of Brothers miniseries. How did you get involved in that project?

BCM: I begged and begged and begged. It was my break in Hollywood. I owe my career to Band of Brothers. I pitched five or six different episodes to Playtone (the production and recording company founded by Tom Hanks and Gary Goetzman). Finally, they gave me the episode no one else wanted to write. That episode, “Bastogne,” eventually won the Writers Guild Award.

HN: Why was getting to work on Band of Brothers so important to you?

BCM: You know, I have no final answer as to why I wanted it so badly. I’ve been obsessed with the Second World War since I was a little boy, but not like most little boys are. I had no interest in the weapons. I was always interested in the moral gravitas of men who have been in combat. I don’t know why. My father never served, my grandfather never served. I was especially fascinated with the war in the Pacific. One of first books I read was about aircraft carriers in the Pacific.

I wrote my honors paper in high school about the common solider of the Second World War. That didn’t exactly please my instructors because it was right after Vietnam, and you weren’t supposed to be interested in war. I interviewed my father’s brother who was a bomber pilot in Italy. I interviewed our milkman—who ironically was a German who had fought against the men of Band of Brothers.

Band of Brothers and The Pacific are the perfect combination to handle this, to tell the story of World War II.

HN: Apart from the unique bond between men depending on each other in combat, The Pacific is a very different situation from that in Band of Brothers. What were some of the unique challenges The Pacific gave you as a writer?

BCM: Band of Brothers was easier. We were working from one source. The Pacific is much grimmer. If you want to know what war does to young men, this is it. Fortunately, we picked books that are very honest.

The writing challenge of The Pacific was the vastness of the campaign. No single group of men went through the entire war.

Steven Spielberg told me he wanted to portray the entire story of the Pacific War from Pearl Harbor to the men coming home, but he also wanted it to be more intense and personal than Band of Brothers. That’s really a challenge, but that’s the definition of an epic. We had to tell the whole story of the war through individual stories. Like the Traffic miniseries, we had to have stories that touched on each other.

I had to do a lot more research on this one. That’s why it took so long to bring it out. I worked from beginning to end with Steven Ambrose’s son Hugh, who wrote the companion book to the series. We never stopped doing research even when on set after filming began.

We brought in many of the same team that helped produce Band of Brothers, so everybody on it had been down this road before. The real challenge was writing it. We didn’t want to just do “Band of Brothers under the palm trees.” We wanted to say something different, to show that experience of men at war and the effect it has on them.

The job of the dramatist is to move people to pity and terror so they reflect on their own lives. I hope The Pacific did that; I spent seven years working on this thing.

HN: The historical situation in the Pacific War was very different from the backdrop of Band of Brothers. You had to depict scenes that sometimes show absolute barbarity.

BCM: Some of the combat sequences are extremely graphic. People are going to have a hard time watching at times. It is much more violent than Band of Brothers. But there is not a single gratuitous act of violence. Every act has a direct effect on the men involved and it accumulates over time. We show some really horrific things and none of it is gratuitous.

As with Band of Brothers, some people are going to like it, some aren’t. There’s only one subgroup who I really, really care about what they think, and that is the men—and now women—who have been to combat. It’s their experience I am trying to depict. That’s who I’m trying to get it right for.

We have to compress events, merge characters. I’m very proud we were able to do this without sacrificing the truth we were telling.

What I’m proud of is the truth of the show—what happens to the souls of men in war, in a necessary war that we had to win. Combat vets who have seen the series are very appreciative of the fact that we got it right.

HN: In episode eight, you tell the story of the wartime romance between Marine sergeants John Basilone and Lena Riggi. What parallels or differences do you see between their story and romances and marriages involving service personnel during today’s wars in Afghanistan and Iraq?

BCM: I think modern warriors of today will recognize and be moved by the story of John and Lena Basilone. We really worked hard, did as much research as we could to get their story right. We interviewed people who had known John and Lena. You know, Lena never remarried although she and John had very little time together. She died with her wedding ring still on her hand and John’s picture in her purse. It is a statement of how intense those relationships could be.

I think service people and their families today will recognize that. Your loved one can be taken away from you and sent away for a year at a time and may not come home.

A lot of fans of Band of Brothers just want to see combat, but war is a crucible in which all emotions are boiled up. That part of the story is huge. When men are at war they depend heavily on the women they are in love with. When that is taken away from them, it is very hard on them. When Robert Lecke’s Greek girlfriend ends their relationship, he begins a downward spiral into blackness.

This is not just a miniseries about combat. It’s a miniseries about war. And war involves mothers and daughters and girlfriends and children and all of society. For dramatists war is the greatest story ever invented because the stakes are so high, not just for warriors but for everybody.

HN: In an interview on HistoryNet‘s partner site ArmchairGeneral, Captain Dale Dye, the military advisor on The Pacific, said he likes to go in very early on a project to work with the writers from the beginning. Did the two of you work together?

BCM: No, not at the beginning. He may have had other projects, but he didn’t come in until we were ready to green light production. We did work together all through filming in Australia, though. Dale vetted all the scripts and was very helpful.

HN: Tell us a little about some of your other writing activities—your book, The Pena Files, and the production work you and your wife, Maureen, did on plays like Neil LaBute’s Filthy Talk for Troubled Times.

BCM: When I dropped out of grad school I was a freelance writer in New York. I wrote for magazines, including a story about Pena. These are great experiences for a writer. You learn your craft, you learn how to write on deadline. When I was “seduced by the lights of Hollywood” and went to LA those experiences gave me an advantage.

I was asked in an interview, “When did you know you’d made it in Hollywood?” I said, “When you find out, call me.”

It’s a constant struggle; you can never relax. I keep the whole experience at arm’s length and take nothing for granted. I regard every job as my first job. If you get complacent, you’re done.

HN: What current projects are you working on?

BCM: I’ve written a script for Frank Darabont (The Shawshank Redemption, The Green Mile) and Phoenix Pictures about the true story of William Mulholland and the rise of Los Angeles. It’s a great epic story.

HN: Is there anything you’d like to add in closing?

BCM: My fervent hope is that this series will motivate people to learn more about the Pacific War. They should learn more, and not just about the American experience. We always intended this story to be universal, so that the Marines’ experiences would speak to a Japanese soldier of World War II, to a young Iraqi of today. It’s not just about the American side of the story but all sides.

Gerald D. Swick edited Historic Photos of World War II: Pearl Harbor to Japan (Turner Publishing Co., 2008). He is senior Web editor for ArmchairGeneral.com, HistoryNet.com, and GreatHistory.com.

To read HistoryNet’s review of The Pacific, see HBO’s The Pacific: About as Real as Hell on Screen can Get by Gene Santoro.