Gideon v. Wainwright leads justices to solidify right to counsel

Historically, the justices of the U.S. Supreme Court have tried diligently to do a good job—but they are human, and they make mistakes. One of their biggest, in 1942, was Betts v. Brady. Scholars rank the decision 21 years later to overturn that ruling in Gideon v. Wainwright among the Court’s dozen or so most important. Gideon concerns a simple, determined man with a checkered past and a compelling claim that American justice had done him an injustice. The issue: if a defendant cannot afford a lawyer, does the government have an obligation to provide that representation?

The topic is as old as the nation. The Sixth Amendment promises that in criminal prosecutions the accused shall have “the Assistance of Counsel”—but says nothing about who pays for that counsel. Congress quickly realized that at times society should. Even before states had ratified the Sixth Amendment, Congress in the Judiciary Act of 1790 provided that in capital cases judges should assign counsel to all defendants who ask for help. Over time

judges came to arrange representation for indigent defendants in serious cases not subject to the death penalty. Local jurisdictions innovated in this arena; in 1913 Los Angeles, California, created a staff of city lawyers whose full-time job was representing indigent defendants. Finally, in 1938, the Supreme Court ruled that the Sixth Amendment requires in every federal criminal case that the government provide a lawyer for a defendant requesting one.

That was in federal courts, however. Most criminal trials take place in state courts. Constitutional Bill of Rights guarantees do not automatically apply to the states. Until the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified in 1868, states were free to set their own juridical rules. The resulting standard—that states must assure “due process of law”—had little meaning until the courts fleshed it out.

Justices hesitated to impose federal rules on state court trials. Only in 1932 did they address the issue of providing defendants with free attorneys, in a notorious prosecution in Scottsboro, Alabama, of nine black teens falsely accused of raping two white women. Voting 7-2, the court held that in some cases—at least when a defendant’s life is at stake—the 14th Amendment requires states to supply not merely legal counsel, but effective legal counsel.

Ten years later, in Betts, the justices expanded on the Scottsboro holding. They refused to apply to state courts the federal court standard that every criminal defendant who wants an attorney must be given one. However, the 1942 ruling in Betts did acknowledge that in some cases an indigent defendant’s access to an attorney was so central to due process as to invalidate the conviction of such a defendant if that representation had not been provided. The tricky part was the “in some cases” proviso. A state court had to appoint a lawyer for an indigent defendant only when “fundamental fairness” demanded the state do so, the Court said. Justice Hugo Black issued a vehement dissent, arguing that states had to provide defendants lawyers in every felony case.

Almost impossible to apply in real life, the Betts standard predictably created not only confusion but a surge of litigation over whether a particular case’s nuances required a lawyer.

Subsequent to 1942, the justices had to consider repeatedly whether a state wrongly withheld legal aid. The court usually found something in a case to trigger assigning a lawyer—improper prosecutorial conduct left unchallenged, or a youthful or unsophisticated or non-English-speaking defendant. The Betts rule simply was not working. When in 1963 the justices conferred privately on Gideon, Justice John Harlan said bluntly of Betts, “It is a freak, and we should get done with it.”

The justices had been seeking a chance to do just that—with a case making a cleanbreak with embarrassing precedent by lacking conditions that by the Betts standard would require a court-appointed lawyer. A path opened when a petition, penciled by hand on lined paper, arrived from Clarence Gideon. Prosecuted for robbery in Florida, Gideon requested a lawyer. The state said no. Finding him guilty, a court sentenced Gideon to incarceration at Raiford Prison in Bradford County. From there he had written to the justices, asking that they look at his plight.

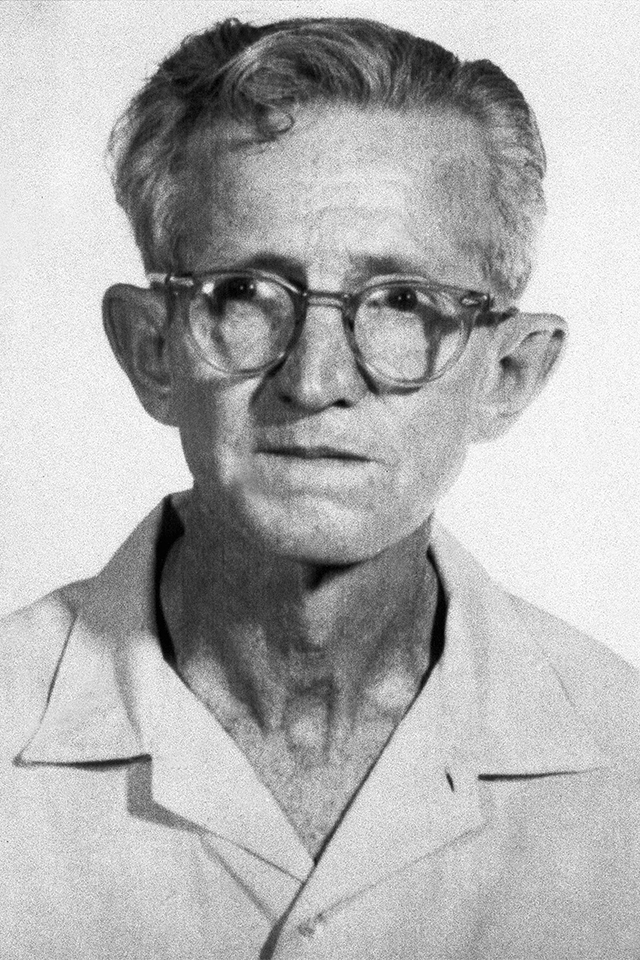

Gideon, 51, had a history of petty crimes. The latest: allegedly breaking into Panama City, Florida’s Bay Harbor Pool Room and stealing change and bottles of beer and soda. A Panama City man testified that he saw Gideon leaving the pool hall at 5:30 a.m. Gideon’s lack of savvy on courtroom protocol sabotaged his efforts to defend himself. He was convicted and sentenced to five years at Raiford. The Florida Supreme Court upheld the conviction, finding that under state law the judge had no duty to see that Gideon had an attorney.

The justices signaled clearly that this was a case in which they wanted to change national legal procedure: to represent Gideon before them, they appointed Abe Fortas, arguably the country’s most persuasive lawyer and soon to become a justice himself.

The court should have appointed a lawyer for Gideon, the justices all agreed. “Due process” demands such representation not only in special circumstances, but in every case, Justice Black explained in the Court’s opinion. “The right of one charged with crime to counsel may not be deemed fundamental and essential to fair trials in some countries, but it is in ours,” he wrote. The decision personally vindicated Black, who 21 years before had assailed the logic of Betts. When the justices overturn a precedent, they typically do so with the excuse that time has brought new insight, obsolescing the prior decision. Not here. Black’s opinion declares, “We think the Court in Betts was wrong.” He told a friend, “When Betts v. Brady was decided, I never thought I’d live to see it overturned.”

Events showed how correct the justices had been to rule as they did. Retried, Gideon was acquitted. His competent lawyer, hired by Florida, managed not only to impugn the sole prosecution witness’s reliability but hinted persuasively the man had been acting as a lookout for the actual robbers.

Clarence Gideon’s exoneration is not the reason Gideon v. Wainwright is one of the most important cases in Supreme Court history. Most states already required lawyers be provided for indigent defendants. In those states Gideon mandated no change. However, it did assure that state policy would not revert. And Gideon did reframe judicial procedure in the few states theretofore unwilling to provide lawyers to indigents. Florida alone released more than 1,000 prisoners because at trial courts in that state had unjustly denied those defendants’ requests for lawyers.

Gideon’s true legacy was to force America to scrutinize its system for providing the poor with legal aid and to institutionalize and rationalize that system. Rather than rustle up a lawyer each time an indigent defendant needed one, states and cities emulated the Los Angeles model, setting up public defender offices staffed with government-employed lawyers assigned to represent indigent defendants. The idea spread after Gideon; every state but Maine has such a program.