“I tried to reflect the life of a soldier as he was going about his work,” Robert Greenhalgh once said of his drawings for Yank in World War II.

On June 17, 1942, the very first edition of Yank, the weekly magazine that the U.S. military published during World War II, rolled off the presses. A gaggle of high-ranking Pentagon officials had come from Washington, D.C., for the launch party in the magazine’s New York City offices, but as the inaugural issue of Yank was passed around, their excitement quickly turned to dismay. Its cover featured a photograph of a grinning GI holding a fistful of dollars in celebration of the recent increase in U.S. Army pay, but in the confusion and haste to get the issue finished, the headline had been changed to read “Why We Fight,” the title of a letter from President Franklin D. Roosevelt that appeared inside. The 50,000 copies that had been printed were hastily removed from circulation.

Despite the early hiccup, Yank would become the most widely read and most popular publication in the history of the U.S. Army. By the end of World War II, some 23 editions had been published (1,614 separate issues in all), and at its height, there were printing presses in the United States, Egypt, Japan, Italy, Trinidad, Saipan, and elsewhere. At its peak Yank, which was staffed entirely by enlisted men, had a circulation of 2.6 million and is thought to have been read by 10 million or so service members. Besides extensive news, photos, and illustrations from the battlefronts, Yank had a sports section, “News from Home,” “Mail Call,” letters, cartoons, and, of course, pinups. By the time the last issue of Yank was published in December 1945, the magazine, with a cover price of 5 cents, had generated a profit of $1 million for the War Department. The overall operation was under the command of Colonel Franklin S. Forsberg, who had been a publishing executive before the war; for most of Yank’s existence, its editor in chief was Sergeant Joe McCarthy, a former sportswriter, who introduced the wildly popular weekly pinup feature.

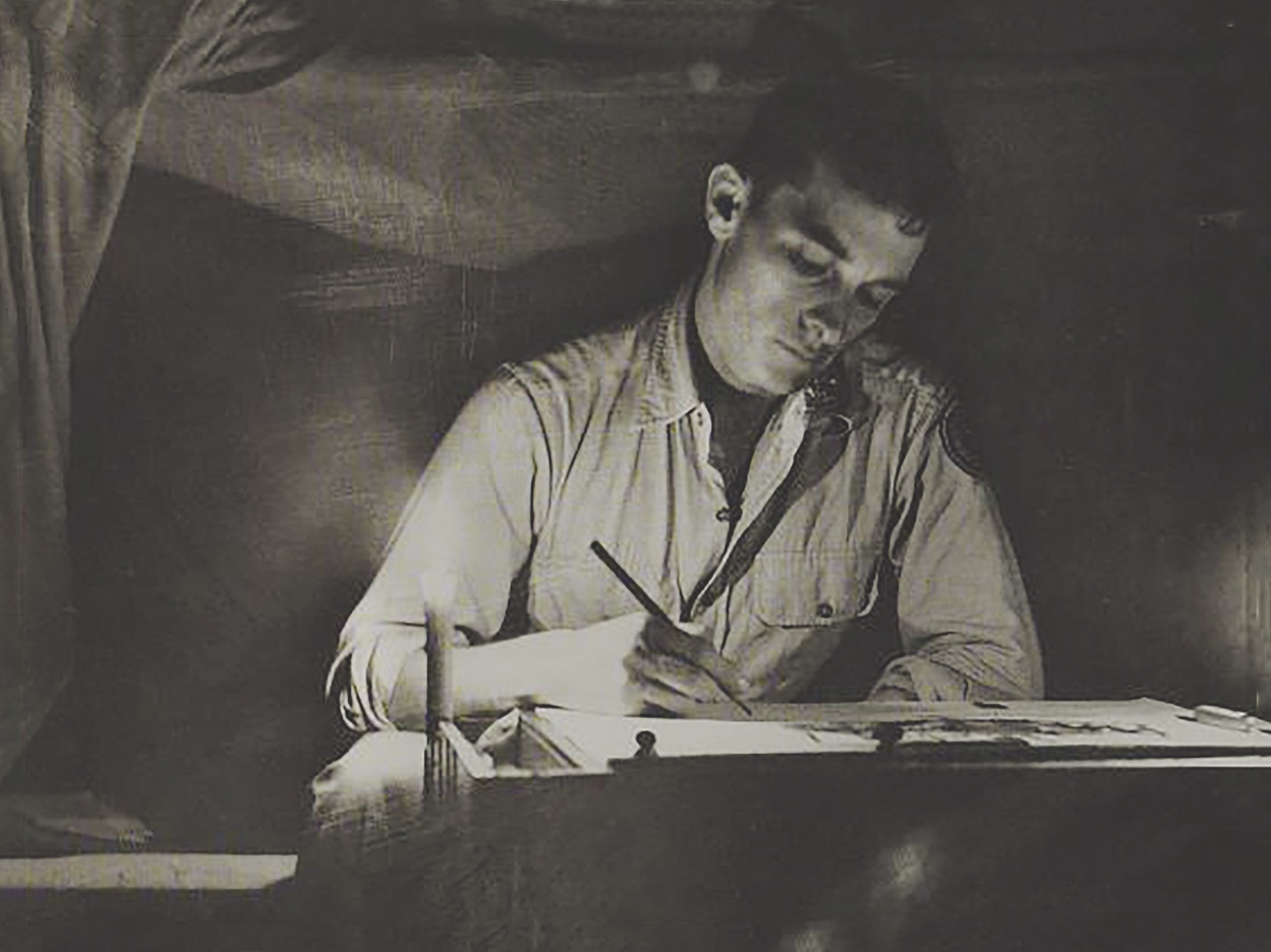

Yank employed writers and artists in its New York headquarters and at the front. One such artist was Robert Greenhalgh. Born in Chicago in 1915, Greenhalgh had earned a journalism degree from the University of Missouri in 1937 and was living with his parents as he tried to make a name for himself as an illustrator, selling his work to such publications as the Chicago Tribune and Esquire magazine. Then, on July 1, 1941, he was called to service in the second draft. A little more than five months later, he was sitting on his bunk at Camp Wolters, Texas, one Sunday when a sergeant rushed into the barrack block yelling, “They bombed Pearl Harbor—we’re in the war!” Greenhalgh was sent to New York City with the rank of sergeant and assigned to the staff of Yank.

Although Greenhalgh was excited to be drawing pictures for the U.S. Army, he felt guilty at times for not being in a combat role. “I felt sometimes apologetic, apologetic because other people had it tougher,” he recalled years later in an interview. “Being in the war, in a war zone, is a whole different ballgame than what we were doing. And nobody kidded themselves about that. And we were soon to find that out, when we were assigned to various places to report the war.”

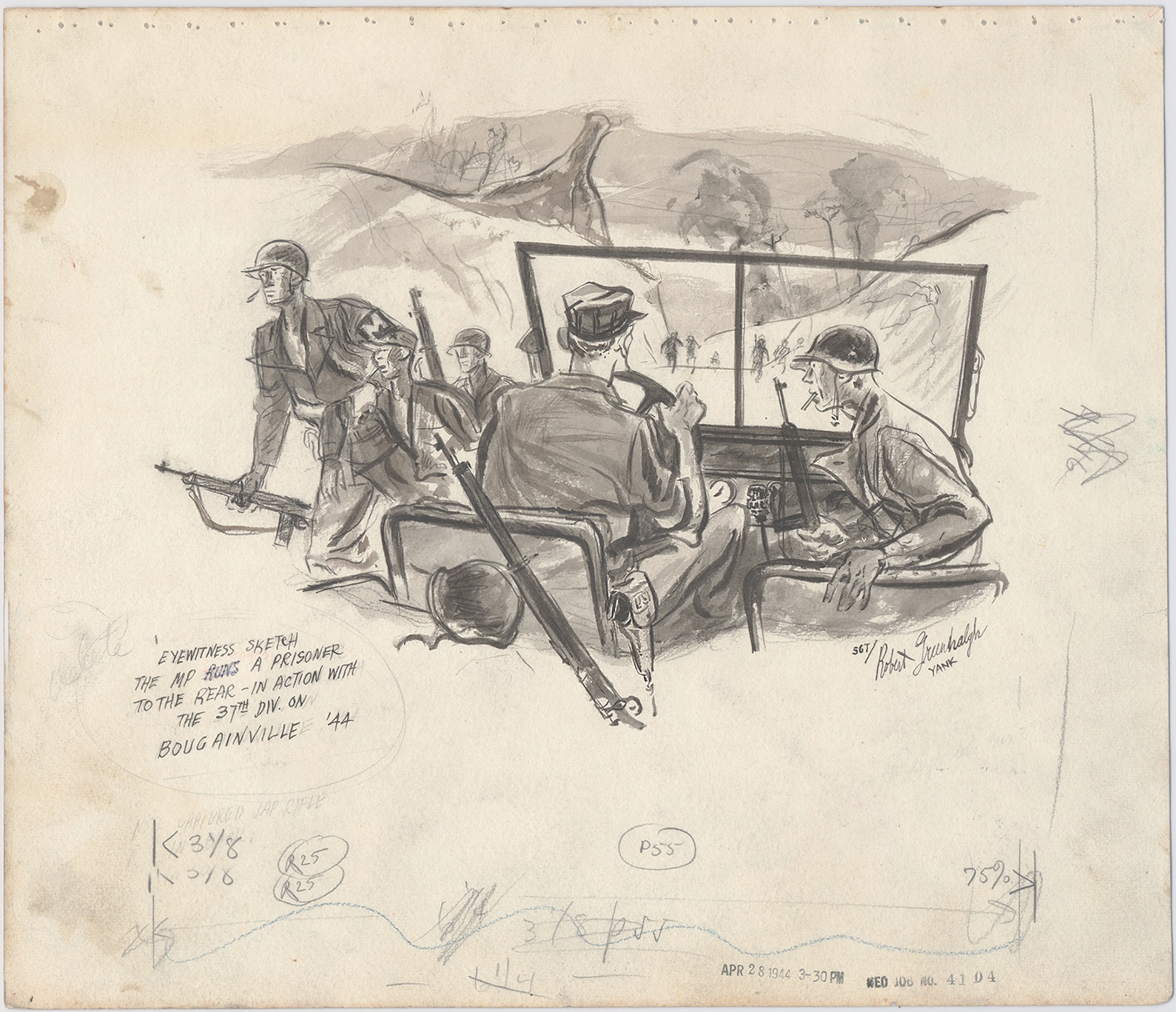

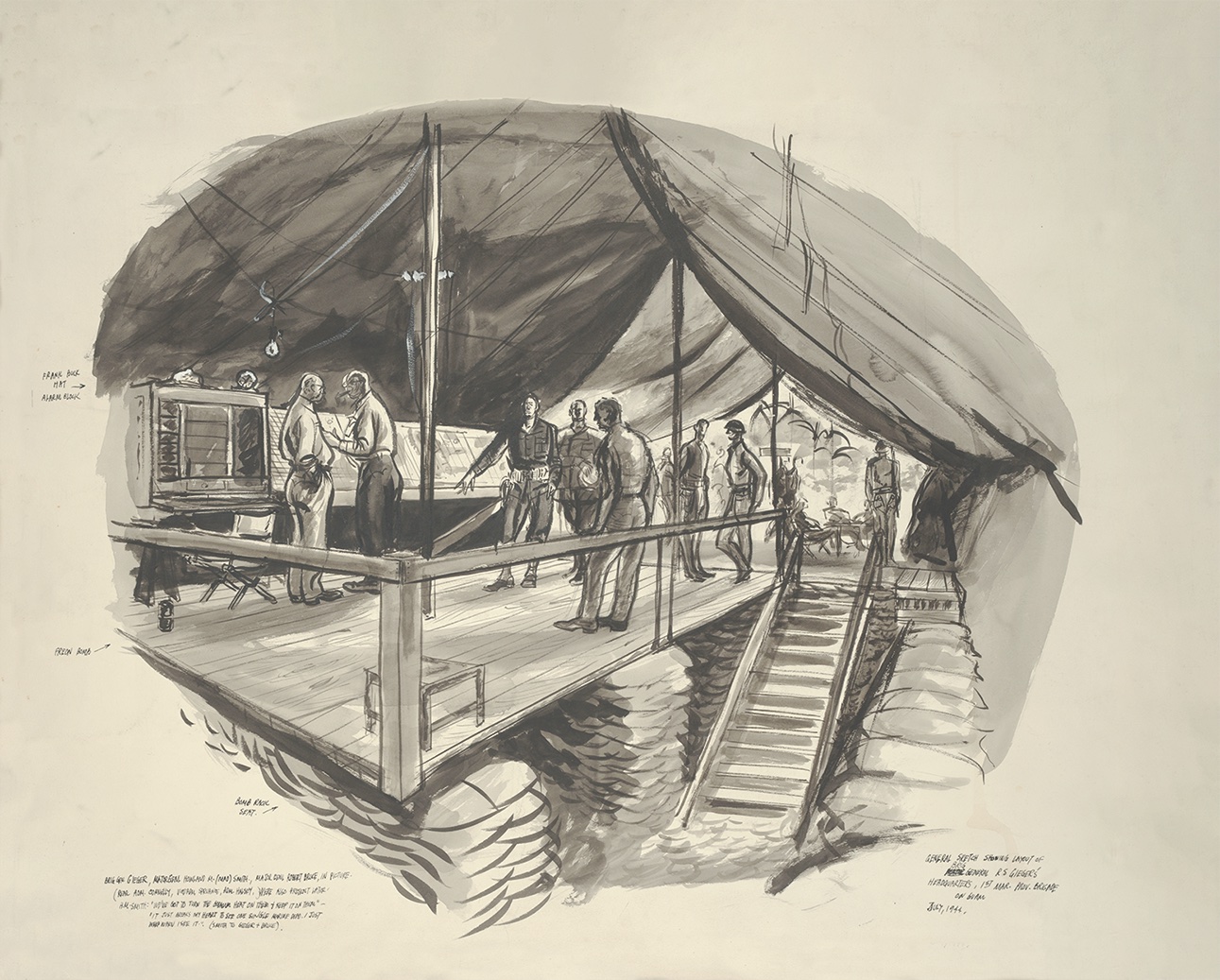

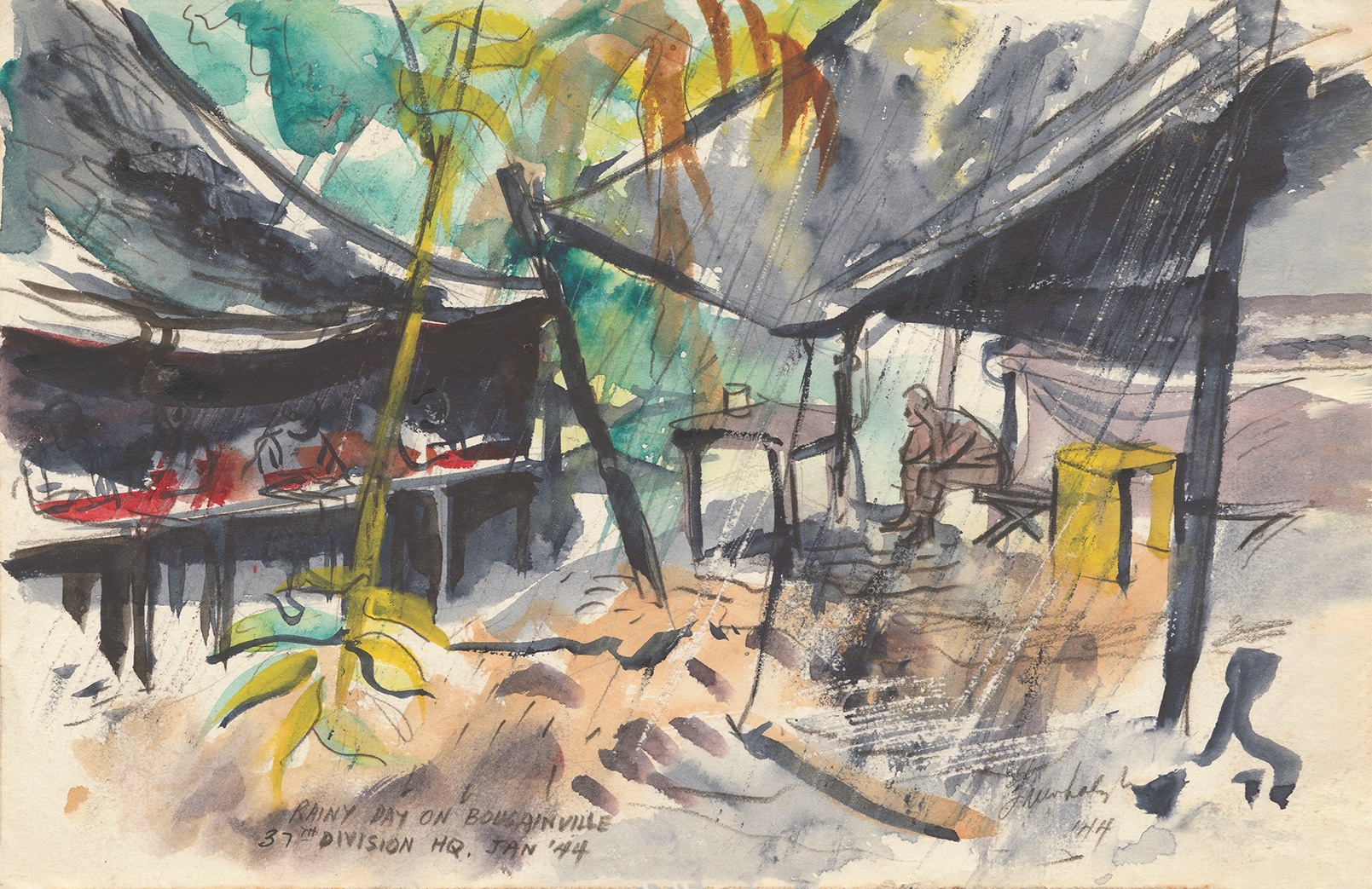

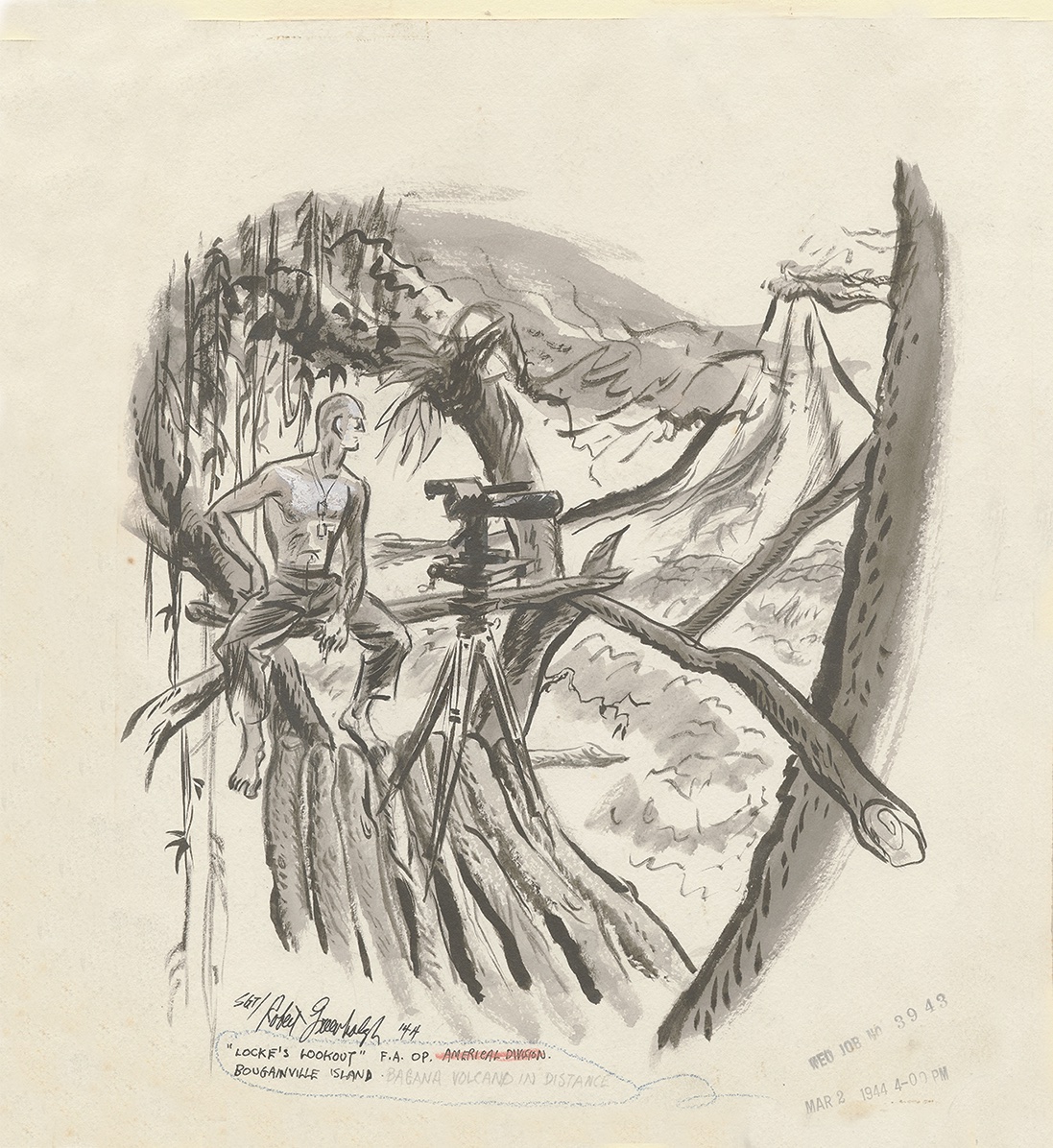

Greenhalgh was assigned to the Pacific theater, where he covered a carrier raid on Wake Island in 1943; U.S. Army operations on Bougainville, New Caledonia, the Solomon Islands, and Guadalcanal in 1944; and the landing on Guam by U.S. Marines the same year. Greenhalgh would spend his days making quick sketches, and in the evenings he would find a quiet spot where he could work up his drawings, in candlelight, so that they could be reproduced in the magazine. All his drawings had to be approved by the U.S. Pacific Fleet’s chief censor, who stamped each piece of paper.

In early 1944, Greenhalgh found himself working alongside William Barrett McGurn, a veteran of the New York Herald Tribune, who had been assigned to Yank as its South Pacific correspondent after he was drafted into the army in September 1942. In a February 1944 letter to Art Weithas, Yank’s art director, Greenhalgh noted that the accompanying 15 drawings were for two stories by McGurn on the local indigenous people. “For Mac’s Inquiring Reporter type story, I have intended the picture of the two guys in a jeep interviewing the natives and the sketches of the native heads be used together in the story—that is as many of them as you choose.” He went on to point out that the main thing the locals wanted were cans of Spam. At the end of a typewritten list of the drawings Greenhalgh wrote: “Note to Censor: Scenery including a portion of skyline or installations are not represented as in reality, but are moved about to suit the purpose of the drawing.” (For artists and photographers, making sure that the locations they depicted couldn’t be identified was a constant concern.)

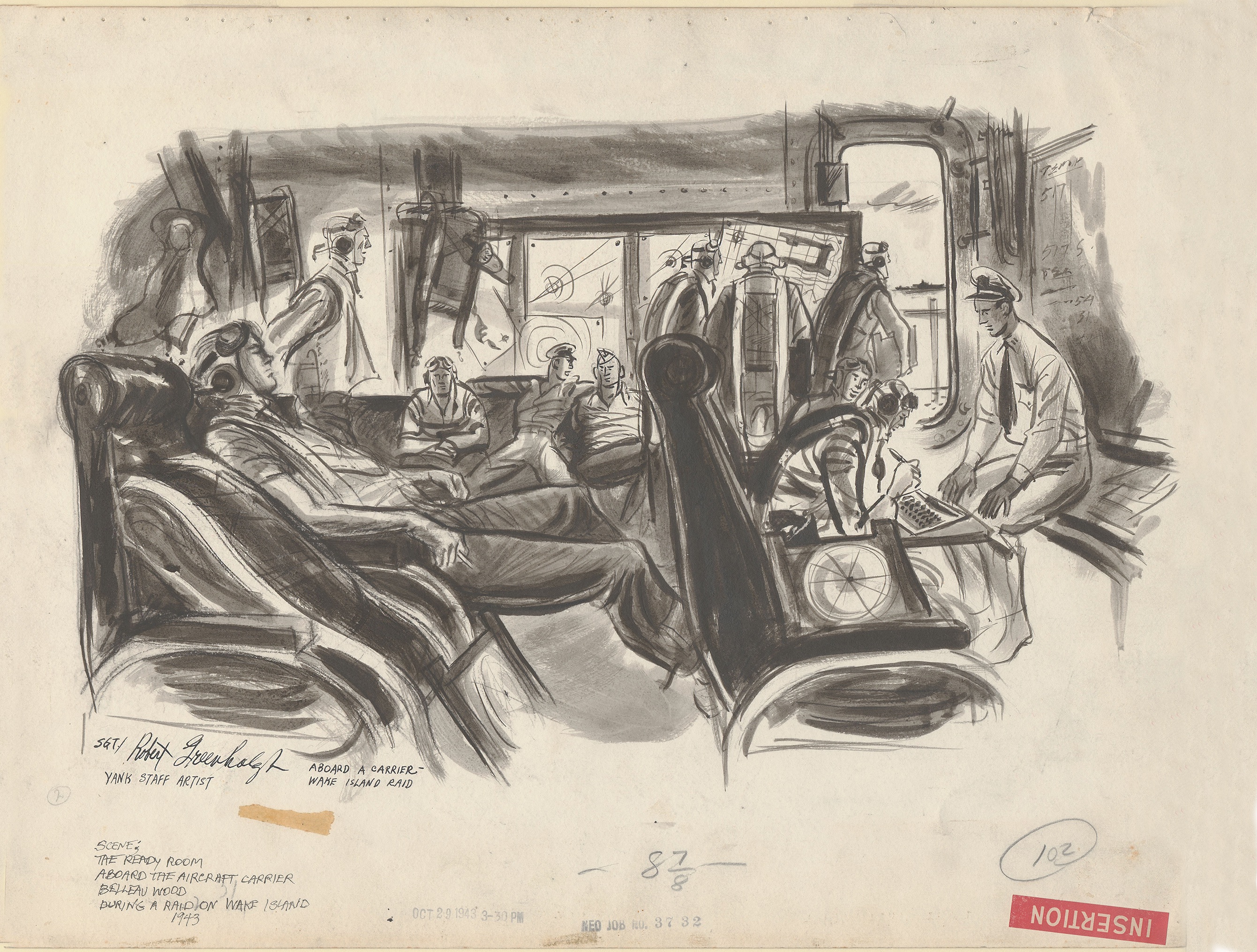

Several months earlier, in October 1943, Greenhalgh had been on board the aircraft carrier USS Belleau Wood when it attacked the Japanese airbase on Wake Island. His drawings were reproduced in Yank on November 19, 1943, with a caption that began: “A YANK staff artist with the Pacific Fleet sketches scenes on an aircraft carrier during one of the most destructive single attacks ever delivered to the [Japanese].” The caption went on to quote Greenhalgh:

When the first striking planes came back to the carrier, you could see holes in some of the wings and cowlings. But when the last strike returned, there were no bullet holes, no torn fabric, and the pilots climbed out unhurt. They said they didn’t see a living soul on the island when they flew away for the last time. Our cruisers laid off shore over there and shelled the [Japanese] positions without ceasing until the guns on Wake were silent.

On another occasion, Greenhalgh witnessed a returning plane plowing into other planes on the carrier’s flight deck, causing a huge explosion and spewing gasoline all over. He later recalled seeing eight or more men running, on fire like torches. Four of Greenhalgh’s drawings show scenes from this event. Several of these pictures ran in the February 25, 1944, edition of Yank to illustrate an article by McGurn titled “Modern Living on a Beachhead in Bougainville.” Another joint effort by Greenhalgh and McGurn, which appeared in the magazine’s March 24 issue, described and depicted the work of the field artillery on the island and the various artillery spotters.

Just off the northern tip of Bougainville in what is now Papua New Guinea lies Green Island, an eight-mile-long atoll that the New Zealand Expeditionary Force invaded the following month. Greenhalgh and McGurn once again teamed up to report on the invasion. The cover of the April 21 issue of Yank featured Greenhalgh’s drawing of four New Zealand infantrymen advancing through the jungle, with a large hog in the foreground. (Hogs, the caption noted, “left the underbrush to give the invasion the once-over.”)

McGurn was wounded shortly after the second battle of Bougainville in March 1944 when a mortar shell fragment hit him in the chest. When asked which outfit he belonged to, McGurn answered “Yank,” to which a soldier commented, “You guys got a racket.” But working for Yank wasn’t without danger: Four of its correspondents were killed in action during the war, and eight, including McGurn, were wounded.

The May 19, 1944, issue of Yank featured another article by McGurn, this one about the second battle of Bougainville, accompanied by Greenhalgh’s illustrations.

In the fall of 1944, Greenhalgh covered the U.S. Marine Corps’ operations from its landing to the capture of Guam airstrip, and the cover of Yank’s October 6 issue bore the headline “A YANK Artist’s Front-Line Sketches from Guam” to highlight a feature that included eight of his drawings. “Slogging around in the rain and mud,” he wrote, “I got my notes soaking wet and now they are almost obliterated,” Greenhalgh wrote in the text that accompanied his drawings. “Then the transport with my art equipment pulled out. But I found some materials on a flagship, so I was in business again.” One of his sketches for Yank shows four marines searching for a Japanese sniper’s nest.

During the fighting on Guam’s Orote Peninsula, Greenhalgh was working with a young Marine Corps press photographer when at one point they became separated. On returning to a safe place after making his sketches, he learned that the photographer had been killed. “It struck me that to be really fair, the war artist should draw only what he has actually seen,” Greenhalgh said years later. “Unfortunately, the war photographer has the extra perilous job of finishing his masterpiece right in the teeth of the battle, as a sort of human tripod, holding his camera in the best and worst of all places.” He also knew Sergeant John Bushemi, a Yank photographer, who was killed on February 19, 1944, while covering the fighting on Enewetak Atoll.

Greenhalgh also made sketches at 10,000 feet in a Martin PBM Mariner of the Naval Air Transport Service en route from Honolulu to New Caledonia. Eight of those sketches were reproduced in Yank on November 10, 1944, including a drawing of the “CPO’s bored pooch Brownie” yawning as he looked out of a cabin window.

For his efforts depicting the war in the Pacific, Greenhalgh received the Award of Distinctive Merit from the Art Directors Club of New York in 1944. One of his last jobs for Yank was to cover the funeral of President Franklin D. Roosevelt in April 1945, after which he was discharged from the army. “I felt pretty lost,” he later recalled. “I was almost afraid to get out of the Army. It seemed to me that was life.” He went on to a successful career as an advertising and editorial artist as well as a television art director for the Young and Rubicam advertising agency in New York City. As a member of the Society of Illustrators, he had several one-man shows. He died at age 102 in October 2017.

Greenhalgh acknowledged that his wartime work was “sketchy and loose,” unlike that of Howard Brodie, his Yank colleague, whose artwork, he said, was “completely drawn and sketched out, which he did so beautifully.” Green-

halgh’s nerves always got the upper hand, and he was eager to get away from danger. He tried to sketch a firefight between the U.S. Marines and the Japanese on Guam, but it was more scribble than anything else. “I was so occupied with nearby flying lead, and other distractions, I couldn’t possibly do a good job of drawing,” he said. Greenhalgh, who knew what it was like to sketch in the line of fire, expressed displeasure when he saw a drawing of “highly finished quality” described as “done on the spot.” Some artists did find creative ways to stay above the fray and finish their work. Greenhalgh once observed Richard Loudermilk, an official Marine Corps artist, seated on top of a telephone pole during a battle, “holding his drawing pad well out in front of him, making a drawing ‘on the spot.’ ”

One thing that stuck in his mind was war as a great equalizer. “You forget about who the other person is,” he said. “That person might not be your same color or background. But you forget about that…everybody seems to be okay. [It’s] something that’s quite unique and special.”

Greenhalgh was one of the many artists and correspondents who went about their business during World War II in a quiet and professional way without much fanfare. “I tried to reflect the life of a soldier as he was going about his work, either as a guy marching off to the frontlines or on the frontlines,” Greenhalgh told an interviewer in 2003. His drawings may have been “sketchy and loose” but they were immediate and easily recognizable, and their simplicity appealed to the enlisted men who devoured every issue of Yank.

Peter Harrington is the curator of the Anne S. K. Brown Military Collection at the Brown University Library in Providence, Rhode Island.

This story was originally published in the Autumn 2021 issue of MHQ Magazine. To subscribe, click here.