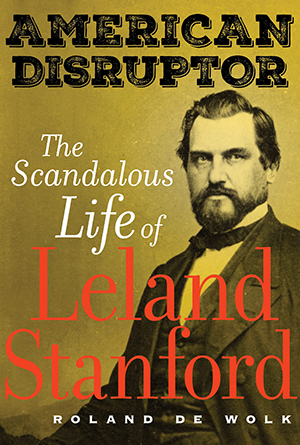

Roland De Wolk earned a history degree at the University of California, Berkeley, spent years as a print, online and broadcast journalist, cofounded an online journalism site and is a senior lecturer at San Francisco State University’s journalism department. That background kept him on track as he researched the life of Leland Stanford, one of the Central Pacific Railroad’s “Big Four” (along with Collis Potter Huntington, Mark Hopkins and Charles Crocker). De Wolk recently spoke with Wild West about his resulting 2019 biography, American Disruptor: The Scandalous Life of Leland Stanford.

What drew you to write about Leland Stanford?

Stanford University is the birthplace (some might say “incubus”) of Silicon Valley. It remains its incubator and sustainer. Having covered many different aspects of the valley and Stanford during my years as a reporter with a history background, it has often intrigued me that there seems so little known about Leland Stanford. The university’s well-funded but tightly wound-up publicity department is very defensive about the school’s founder. As a reporter I wanted to know why.

What makes Stanford so compelling and, in your view, so unlikable?

The enigma surrounding his history is the first thing that makes him interesting. As I was able to really reveal what he was to American history, his story went from interesting to fascinating. As for his likability quotient, I’m not confident many people of wealth and power have ever seemed all that amiable. His feckless youth transforming into arrogant adulthood certainly doesn’t make for someone you’d want to join on a family vacation.

What is there to like about Stanford?

His true-blue loyalty to his family merits admiration, some respect and a measure of likability. I would have to add that I also, in an odd sort of way, liked his persistence and ability to pivot, even if the ultimate aim for money and power appears shallow. Certainly, being a principal in the construction of the nation-changing transcontinental railroad is worthy of liking the guy on some level.

What was the hardest aspect of researching Stanford’s life?

What was the hardest aspect of researching Stanford’s life?

His widow, Jennie, destroyed all their correspondence shortly after he died. This alone has been a major obstacle to others who have tried, I might say futilely, to seriously research his life. There is reason to believe she also destroyed her own private diary toward the end of her life. Yet, in scouring reminiscences of his contemporaries and public documents slowly—painfully slow—a portrait finally emerged. I was particularly lucky in getting access to some 500 letters and telegrams he sent to Huntington, now in the rare books collection of Syracuse University’s library. A few scholars have been through those, but because they were interested in the more colorful Huntington, they seemed to have largely overlooked the Stanford trove.

How did a fellow with such an unpromising start become one of the wealthiest and most powerful men in America?

One might say he finally grew up when he hit the bottom of the barrel in Wisconsin. One could argue that his brothers, especially his oldest sibling, Josiah, rescued him and brought him to California. One could make the case that landing next to Huntington, Hopkins and Crocker was the luckiest break in his life. Then there’s his chance meeting with Theodore Judah. I would say we have to give Stanford some credit for recognizing a lucky break, an opportunity, and exploiting it. Lots of people never do. I feel compelled to add from Ecclesiastes: “I returned and saw under the sun that the race does not always go to the swift, nor victory to the strong…but that time and chance happen to all.”

What brought him to California?

Failure. He failed in his native upstate New York. He failed in his attempt to reboot in Port Washington, Wis. We Californians are accustomed to seeing people who fail in other places come here and think they can make it. They almost always fail, but Stanford was one of those rare ones who did not. The Gold Rush brought his brothers here, and without the beachhead they secured for him, Leland would have almost certainly screwed up again.

‘Without Stanford bullying state and local governments to extract tax dollars to support his private enterprise, the transcontinental railroad would not have been built’

What was his role in the transcontinental railroad, and how does he stand in the Big Four?

The conventional history of the transcontinental railroad usually diminishes Stanford’s role in the enterprise’s success. And some serious historians have dismissed the railroad’s conventional standing as a success itself, I should add. I do not. And I would argue that without Stanford bullying state and local governments to extract tax dollars to support his private enterprise, it would not have been built.

Insofar as comparing him to the other three of the Big Four, I do believe he carries his own weight. Huntington, not to be slighted because he was a man, as his biographer David Lavender wrote, with a “creative imagination of singular daring.” But it must be said he left a vast amount of self-serving correspondence that has helped him look good. Hopkins was a quiet guy and rarely did anything so odious as either Stanford or Huntington, so he looks fairly benign. Crocker just whipped his railroad crews through his foremen.

What were Stanford’s pluses and minuses as governor of California?

Pluses…hmmm. I’ll have to get back to you on that. Minuses? He used his Republican Party platform to promise to reduce the state budget deficit. (They were allowed in those days.) He instead forced the state Legislature to borrow even more money by raising taxes—through bond issues, which of course burden taxpayers with still more debt—for his private railroad company. He sanctioned massacres of native peoples, especially in northern California. He screwed up a massive prison escape at San Quentin that ended in a slaughterhouse massacre. Fortunately, he was governor for only two years. Oh, he screwed up his reelection chances as well.

What prompted the founding of Stanford University?

His only child, Leland Stanford Jr., died at age 15. Leland Sr. and Jennie saw the university as a lasting memorial to their fallen son.

How did his son’s death affect Stanford?

By all accounts, deeply. The loss of a child, of course, is perhaps the worst experience any mother or father can have in life. I found a never-published letter from Mark Twain who wrote at the time Stanford “at once lost all interest in life.” Bertha Berner, who wrote an account of her life as Jennie Stanford’s private secretary, said “Mr. Stanford broke down completely, Mrs. Stanford fearing for his reason and his life.” These sentiments are found throughout the research.

What did you discover about the Stanfords’ elaborate mourning rituals?

An exhibit at the Stanford University museum noted the extraordinarily extravagant cortège and mourning rituals the Stanfords employed for their grief. “Even by Victorian standards,” the exhibit (now overhauled) stated, “the Stanford’s mourning was staggering in its public display: Leland Jr.’s body was transported home in a series of funeral processions conducted over eight months, lying in state in Paris, New York and finally in San Francisco.”

Discuss the murder of Stanford’s widow and how you researched that episode.

Her murder in a luxurious Honolulu hotel is indeed intriguing. I get asked a great deal about that at almost every event where we talk about the book, especially by women, who all too rarely are respected and written about by historians. For me—and this is the old investigative reporter talking—the cover-up by the president of the university is at least as important.

Researching this required reading the police accounts, the voluminous coroner’s investigation, newspaper accounts and The Mysterious Death of Jane Stanford, the all-important, if slim, 2003 book by the late Dr. Robert Cutler, a Stanford University professor of medicine, who brought his modern medical scholarship to the case. I even interviewed contemporary homicide detectives to get their insights. I am told a noted professor of history at Stanford is writing a book just about the murder. I am very much looking forward to it.

‘Leland Stanford can be fairly credited with being instrumental in building modern America under some of the most trying circumstances imaginable, underscoring the American catechistic faith of what a person can accomplish when purpose and perseverance unite’

How should Leland Stanford be remembered?

I have trouble answering that important question with any crispness. I did write he was “an ordinary man who found himself in extraordinary circumstances.” I added, in American Disruptor, “What Stanford did—what he accomplished— in the state of affairs he found himself in, is seldom met in the course of human events. He was certainly guilty of many shabby performances, but given the stage he found himself on, unprepared by upbringing, temperament and history itself, what else can be fairly expected of a man? And yet, Leland Stanford can be fairly credited with being instrumental in building modern America under some of the most trying circumstances imaginable, underscoring the American catechistic faith of what a person can accomplish when purpose and perseverance unite. That he as a young man could not possibly have been admitted as a student to the university he created toward the end of his life signifies his ultimate success rather than his penultimate failures.”

What’s next for you?

More unexplored, unwritten, important American history! My next book, now well under way, is more 20th century, again with a tilt to the most populous, prosperous, important part of the nation—the West. It is tuned to a more mass-market audience, although it will employ the same high scholarly standards of research and verification.

Anything else you want to add?

Napoléon is supposed to have said, “Give them history. Men should read nothing else.” Someone I have worked with countered with some wisdom from The Andy Griffith Show: “History? There just seems to be more of it every day.” WW

This interview was published in the October 2020 issue of Wild West.