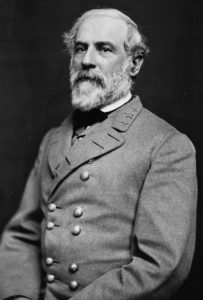

Facts & information about Robert E. Lee, a Confederate Civil War General during the American Civil War

Robert E. Lee Facts

Born

January 19, 1807

Died

October 12, 1870

Beginning Rank

Major General, Virginia state troops

Highest Rank Achieved

General, Confederate States of America

More About Robert E. Lee

Robert E Lee’s Horse Traveller

Robert E. Lee’s Surrender

Seven Days Battle

Battle Of Fredericksburg

Battle Of Chickamauga

Battle Of Antietam

Battle Of Chancellorsville

Battle Of The Wilderness

Battle Of Gettysburg

Battle Of Spotsylvania

Cold Harbor

Appomattox Court House Battle

Robert E. Lee Pictures

Robert E. Lee pictures, images, and photographs

» See our Robert E. Lee Pictures.

Robert E. Lee Quotes

Quotes from Robert E. Lee

»See our Robert E. Lee quotes.

Robert E. Lee Articles

Explore articles from the History Net archives about Robert E. Lee

» See all Robert E. Lee Articles

Robert E. Lee summary: Confederate General Robert E. Lee is perhaps the most iconic and most widely respected of all Civil War commanders. Though he opposed secession, he resigned from the U.S. Army to join the forces of his native state, rose to command the largest Confederate army and ultimately was named general-in-chief of all Confederate land forces. He repeatedly defeated larger Federal armies in Virginia, but his two invasions of Northern soil were unsuccessful. In Ulysses S. Grant, he found an opponent who would not withdraw regardless of setbacks and casualties, and Lee’s outnumbered forces were gradually reduced in number and forced into defensive positions that did not allow him room to maneuver. When he surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865, it meant the war was virtually over.

Robert Edward Lee was the fifth child of Revolutionary War hero and governor of Virginia Henry “Light-Horse Harry” Lee. Henry Lee, unfortunately, was fiscally irresponsible, which hurt the family financially, and he left for the West Indies when Robert was six, never to return. Robert’s mother, Ann Carter Lee, raised the boy with a strong sense of duty and responsibility.

Robert secured an appointment to West Point in 1825. Graduating second in his class in 1829, with no demerits, he entered the prestigious Engineer Corps. Throughout the peace of 1830s and early 1840s, he was assigned to posts from Georgia to New York and rose from second lieutenant to captain. In 1831 he married Mary Anna Randolph Custis, great-granddaughter of George Washington’s wife Martha and her first husband, Daniel P. Custis. As a result of wedding Mary, Lee improved his financial position and his name became associated, however distantly, with the Revolutionary War commander and first president, something that added to his reputation during and after the Civil War.

Robert E. Lee in the Mexican War

When the United States went to war with Mexico in 1846, Lee won laurels on the staff of Major General Winfield Scott, who commanded the American forces that invaded Veracruz and captured Mexico City. As an engineer, Lee helped Scott find ways around Mexican strongpoints or to capture them.

This experience undoubtedly played an important role during the Civil War, when he was always looking for a way “to get at those people over there,” the Federal armies that he often thwarted. Breveted three times for gallantry in Mexico, Lee crossed the nearly impassible hardened lava beds of the Pedregal in storm and darkness to inform his commander of the position of Scott’s advance troops on the other side. He then crossed the inhospitable area again, guiding Scott’s follow-on troops to surprise and defeat the Mexican force at Contreras. Scott’s estimation of Capt. Lee could not have been higher; one observer called it, “almost idolatrous.”

Lee as Superintendent of West Point

After Mexico agreed to a peace settlement in 1848, Lee returned to duties in a peacetime army. On September 1, 1852, he became superintent of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, where he oversaw changes to the curriculum and added a fifth year to the traditional four. In 1855, Congress authorized the formation of four new regiments and Lee, leaving the engineers where promotion was slow, became a lieutenant colonel in charge of the 2nd Cavalry Regiment. For the next six years, he was stationed with them in Texas, primarily overseeing operations against the Comanches and performing staff duties.

In October 1859, while Lee was on one of several trips east to settle the estate of his wife’s father, radical abolitionist John Brown and a band of followers seized the U.S. arsenal at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia. The War Department ordered Lee to handle the situation and, leading a U.S. Marine detachment, he quickly recaptured the arsenal.

Lee Enters The Civil War With The Confederecy

Several states of the Deep South seceded in protest over the 1860 election of Abraham Lincoln as president, and the newly formed Southern Confederacy offered Lee the rank of brigadier general. He ignored that offer, but the bombardment of U.S. troops in Fort Sumter at Charleston, South Carolina, on April 12–14, 1861, placed him in a difficult position. His former commander, Winfield Scott, offered him command of the army of volunteers being raised to suppress the rebellion; that same day, Virginia voted in favor of secession. Lee did not support secession, but he would not fight against his native state. He resigned his officer’s commission, wrote Scott a personal message of thanks and regret, and became a major general of Virginia troops, commanding all military forces of the state.

After Virginia officially joined the Confederacy and its governor transferred all the state’s troops to that body, Lee became a Confederate major general—for all of two days, after which the Confederate Congress made him their army’s third full general, ranking behind Samuel Cooper and Albert Sidney Johnston. He became military advisor to Confederate President Jefferson Davis and, on July 28, the president asked him to coordinate the defenses of Western Virginia, where the citizens were attempting to create a new, Union-loyal state and Confederate arms had already met with defeat at Philippi and in the Big Kanawha Valley.

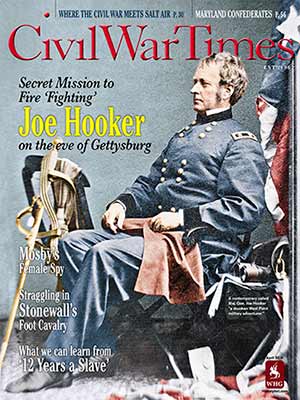

Read More in Civil War Times Magazine

Read More in Civil War Times Magazine

Subscribe online and save nearly 40%!!!

Lee committed an error common to military leaders at this stage of the war: he devised a plan too complicated for the volunteer troops and bickering commanders to carry out, especially in a mountainous area plagued with bad roads. Defeated at Rich Mountain by Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan’s force, he returned to Richmond as “Granny Lee,” his previously glowing reputation under a cloud. The Richmond Examiner decried him as unwilling to shed blood and “to depend exclusively upon the resources of strategy … without the cost of life.” While in Western Virginia, however, Lee first encountered Traveller, the horse that would carry him through most of the war and become nearly as famous an icon as Lee himself.

Lee’s next assignment was head of a department comprised of the coastal regions of South Carolina, Georgia and eastern Florida. The engineer spent four months overseeing the construction of coastal defenses. In March 1862, he was back in Richmond, assigned to manage “the conduct of military operations in the armies of the Confederacy.” In that role, he successfully supported a conscription act, passed by the Confederate Congress April 16. His support of the act may not have been as convincing to the Congress as the 100,000-man Army of the Potomac that George McClellan was advancing up the Virginia peninsula toward Richmond.

McClellan’s troops clashed with the Confederates under Gen. Joseph Johnston in the Battle of Seven Pines, also called the Battle of Fair Oaks, on May 31. When Johnston was wounded and taken from the field, Davis asked Lee to assume command of the army.

General Lee Takes Command of the Army

Knowing he could not win by retreating into defensive works, within three weeks Lee took the offensive, initiating the Seven Days Battle, a series of fights that drove the Federals back down the peninsula. In the final battle, Malvern Hill, Lee threw his men in a series of costly charges against strong Union positions but failed to take the hill. Perhaps Lee was looking to dispel his “Granny Lee” reputation; perhaps he was remembering that frontal assaults had often worked in Mexico; perhaps he sensed victory was just one more charge away. Whatever his reason, the Seven Days showed both his capacity for maneuver and surprise and his willingness to sustain significant losses in pursuit of victory, traits that would arise again. Lee had driven the enemy away from the gates of Richmond, however, and his star began to rise in the South.

He next moved north, his Army of Northern Virginia divided into two corps, the larger under the command of his “Old War Horse” Lt. Gen. James Longstreet, and the other under Lt. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson. In the Battle of Second Bull Run—Second Manassas to the Confederates—Lee defeated Maj. Gen. John Pope. A month later, September 1862, Lee led his army in its first excursion onto Northern soil, crossing the Potomac into Maryland. That campaign ended at the Battle of Antietam (Sharpsburg) on September 17, the bloodiest single day in all of American history. At the end of that day’s fighting, he calmly assessed that the cautious McClellan would not renew the contest and allowed his men a day of rest before withdrawing back into Virginia.

The following December, McClellan’s replacement, Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside, stole a march on Lee but failed to cross the Rappahannock River promptly. The resulting Battle of Fredericksburg slaughtered the right wing of Burnside’s army.

At the end of April 1863, a fourth Union commander, Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, tried to outflank and defeat Lee. The result was what is widely regarded as Lee’s greatest victory, the Battle of Chancellorsville. Boldly dividing his army in the face of superior numbers, the “Gray Fox” repulsed Hooker’s main force, then turned and stopped the rest of the Army of the Potomac at Salem Church.

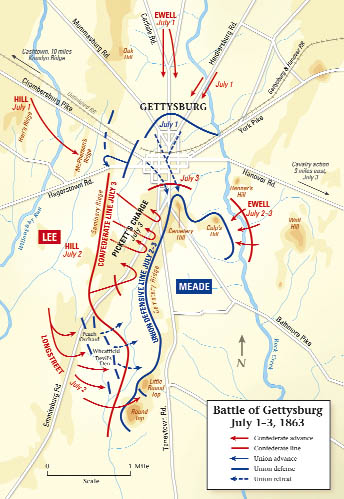

The Gettysburg Campaign

In June, Lee again led his troops in an invasion of the North, this time striking into Pennsylvania. He was not well, physically or emotionally. The symptoms of heart disease were becoming evident, and the general still grieved the death of his 23-year-old daughter, Anne Carter Lee, the previous October. He had also lost his “right arm,” Stonewall Jackson, who had been mortally wounded by his own men at Chancellorsville.

Lee had always shown an inclination to issue orders that gave subordinates significant latitude in carrying them out. During the Gettysburg campaign, that proclivity allowed his cavalry commander, J.E.B. “Jeb” Stuart, to decide on a wide swing behind Union lines that took him out of contact with the rest of the army and denied Lee crucial intelligence on enemy movements. Jackson’s old corps had been split in two, and the new commanders needed a firmer hand than Lee applied, which may have cost him the high ground at the Battle of Gettysburg. There, he repeated his mistake of Malvern Hill, sending the divisions of Maj. Gen. George Pickett and Brig. Gen. James Pettigrew across a mile and a quarter of open ground against a strong Union position on Cemetery Ridge. Pickett’s Charge, as it became known, resulted only in a monumental loss of soldiers Lee could not replace, and his second northern invasion failed.

In November he turned back an indecisive movement by Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade, the victor of Gettysburg, during the Mine Run Campaign, but soon Lee faced a more determined foe.

Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant had been summoned from the Western Theater to command all Union armies in the field and attached himself to Meade’s Army of the Potomac. In the bloody Overland Campaign in the summer of 1864, Grant and Lee faced each other in the Wilderness, at Spotsylvania, and Cold Harbor. Always, Lee was able to withdraw after inflicting severe casualties on the Federals, but they could replace their fallen better than the South could. Finally forced back to the Petersburg–Richmond area, Lee again used his engineering skill to create extensive defensive works that held back his opponents until the spring of 1865.

Lee’s Surrender And The End Of The Civil War

He was named commander-in-chief of all Confederate armies on January 23, 1865, but it was too late for coordinated action between the theaters and the dangers in Virginia occupied most of his attention. Finally forced out of his defensive works, he surrendered to Grant on April 9 at Appomattox Court House, though some of his commanders had urged him to lead a guerrilla war in the mountains. Lee’s surrender was the signal that the Southern cause was truly lost. Other Confederate armies soon capitulated as well. Read more about Lee’s Surrender

Lee After The Civil War

His wife’s home at Arlington had long been occupied by Union troops and its lands turned into a cemetery for their dead. Lee and his family lived in Richmond until he accepted a position as president of Washington College (later renamed Washington and Lee University) in Lexington, Virginia, later in 1865. On October 2, 1870, the heart disease that had plagued him for at least seven years finally claimed the old warrior.

Read More in America’s Civil War Magazine

Read More in America’s Civil War Magazine

Subscribe online and save nearly 40%!!!

He had become a symbol of Southern resistance to the Union armies and was made an icon of the Lost Cause in the post-war South. Today, he remains internationally respected as a daring, often brilliant tactician, a gentleman who never referred to Northern soldiers as “the enemy” but as “those people over there,” a man who opposed secession but felt honor-bound to serve his native state. He applied for restoration of his American citizenship, but the papers were lost until the 1970s, when his wish was granted.

Articles Featuring Robert E. Lee From History Net Magazines

Featured Article

Did Robert E. Lee Doom Himself at Gettysburg?

By blindly relying on poor intelligence and saying far too little to his generals, Lee may have sealed the Rebels’ fate.

The afternoon of July 3, 1863, near Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, promised to be hot. A town resident with a scientific bent would record a high temperature of 87 degrees for this day. At his headquarters just west of town, alongside the Chambersburg Pike, Gen. Robert E. Lee was feeling a heat that had little to do with the sun. Everywhere he looked men, animals, and weapons were moving with a sense of purpose instilled by orders he had given just a short time before. A climax to two days of battle was coming, announced by an action sure to be bloody, and certain, he fervently hoped, to be decisive.

To anyone passing by the modest headquarters tent, the 56-year-old commander of the Confederacy’s finest army appeared, as one soldier recalled, “calm and serene.” There is no reason to believe otherwise. “I think and work with all my power to bring the troops to the right place at the right time; then I have done my duty,” Lee said. “As soon as I order them into battle, I leave my army in the hands of God.”

Over the course of the morning, an unnatural peacefulness had spread across the battlefield save for the occasional pop of a distant rifle firing. Then, at seven minutes past one o’clock, Lee heard a signal cannon shot followed, after a short pause, by a second. No one needed to tell him what it meant. The attack that was to decide the battle, and perhaps the war, was beginning.

A great deal would be written about the events at Gettysburg. Lee himself would submit three different reports explaining the critical decisions he made this day and the two days immediately before it. In them he would imply that his principal lieutenants had come up short, and would even wonder if he had asked his men to do too much.

But missing from his analysis was any recognition that he based his plans on a great deal of field intelligence that he might have guessed was flat-out wrong, that, given the circumstances (especially the absence of his favored cavalry chief, which forced Lee to rely on information from less trustworthy substitutes) he should at the very least have treated with far more caution.

Nor does it indicate that General Lee ever asked himself if he could have done more to ensure that those empowered with executing his orders fully understood his intentions. To put it bluntly, it is clear these 146 years after his reflections that Lee—even though he had just completely reorganized his army, with new officers serving at all levels—failed to see that his battle instructions were fully communicated to all of his commanders. It wasn’t the first time, nor would it be the last, that a battle turned on a misapprehension or miscommunication. Gettysburg had more than its share of both, however, due in no small part to Lee’s hands-off management style—and his determination to make this battle the one that changed the war.

Lee had been on the road to Gettysburg from the start of the conflict. From the moment he was placed in command of the Army of Northern Virginia, he believed that the Confederacy’s survival depended on expanding the fighting deep into Union territory. Even as he struggled to hold back a massive Federal army under Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan that was threatening Richmond in 1862, he tried to assemble a sufficiently strong force for Lt. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson to invade Pennsylvania from the Shenandoah Valley. It wasn’t to be; the resources of the Confederacy were spread too thin. But the impulse became an idée fixe in Lee’s strategic thinking.

When he led Confederate forces into Maryland in September 1862, in the operation climaxing at Antietam, he intended to press through the border state into Pennsylvania. Once again, circumstances forced him to divert. Following the battle of Chancellorsville (May 1–3, 1863), Lee found himself in an administrative tug-of-war with Richmond over the control of his army. Certain powerful officials wanted to detach pieces of it to prevent the loss of Vicksburg in Mississippi.

Lee argued that allowing him to march north would accomplish the same thing, by capturing the enemy’s attention and diverting Federal reinforcements that otherwise would be sent west. Besides, as he would later state, an “invasion of the enemy’s country breaks up all of his preconceived plans, relieves our country of his presence, and we subsist while there on his resources.” In the end, President Jefferson Davis backed the only general who could deliver him victories. Granted permission to mount his operation, Lee assured Davis that any advance would be carried out “cautiously, watching the result, and not to get beyond recall until I find it safe.”

Despite his promise, Lee never seriously considered halting the campaign once he commenced disengaging from the Union Army of the Potomac near Fredericksburg, Virginia. Even a wholehearted Federal strike at his cavalry force camped around Brandy Station, Virginia, on June 9, did not deter him. By June 16, the entire Army of Northern Virginia (70,000 men, comprising three infantry corps plus cavalry and artillery) was stretched out in a long column whose tail was just departing Fredericksburg even as its head was approaching the Pennsylvania border. Six days later his advance commander—Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell, in charge of the Second Corps—was handed instructions sanctioning the capture of Harrisburg should the situation become favorable.

On June 28, headquartered outside Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, Lee was poised to commit his force to a broad sweep to the east as far as the Susquehanna River. His goal was not to take northern territory, but to hurry the Army of the Potomac into a showdown. As he explained to one of his senior commanders, he fully expected to “throw an overwhelming force on their advance, crush it, follow up the success, drive one corps back and another, and by successive repulses and surprises before they can concentrate; create a panic and virtually destroy the army.” Only then, Lee believed, could the Confederacy expect to talk peace with the North on advantageous terms.

But several days earlier he had made a fateful decision that would afterward be seen as critical to the outcome of this operation, and a significant factor in the intelligence failures at Gettysburg. His cavalry, under Maj. Gen. James Ewell Brown “Jeb” Stuart, had been tied down in northern Virginia protecting the right flank of his infantry columns tramping north through the Shenandoah Valley. Lee needed his horsemen with Ewell’s Corps in the advance and listened as Stuart proposed to get to the head of the line by riding east and then north, behind the Union columns thought to be scattered in a disorganized pursuit. Stuart’s ingenious work at Chancellorsville made Lee comfortable granting broad discretion to his cavalry chief, even though senior subordinates like Lt. Gen. James Longstreet felt that Stuart required “an older head to instruct and regulate him.” Lee agreed to Stuart’s plan, estimating it would take three days before his cavalry chief would be back in contact. Stuart departed with most of his riders early on the morning of June 25.

Three days later, there was no word from Stuart and no reliable information as to where he was. In the absence of intelligence, Lee assumed that all was going according to plan and that his opponent was spread thin in a protective arc shielding the immediate approaches to Washington, leaving the way clear for his advance to the Susquehanna River. His mental image of an enemy disorganized and hesitating to intervene seemed borne out. But it was on this very night of June 28 that he learned from an irregular scout employed by Longstreet, his First Corps commander, that the Union army was much closer and more concentrated than he had imagined.

Very suddenly, the risk to the long Confederate column had increased exponentially.

Lee had no recourse but to dramatically alter plans. A phalanx of couriers hurried out from headquarters with fresh instructions for the army to draw together. It was Lee’s intention to regroup his potent force just east of the Catoctin Mountains around the village of Cashtown, Pennsylvania. Confident he would have his army well in hand before the Federals began arriving in strength, he still anticipated attacking and defeating them a piece at a time as they scrambled to confront him.

When Lee entered the western end of the Cashtown Pass on the morning of July 1, everything was going according to the new plan. Ewell’s Corps was falling back from its advance positions along the Susquehanna River (two divisions marching southward, the third on a roundabout route that brought it traveling east through the pass later that morning), Lt. Gen. Ambrose Powell Hill’s Third Corps was already on the eastern side of the pass, and Longstreet’s First Corps was due to complete its passage by day’s end. Union cavalry had been reported in the area, so when Lee reached the midpoint and heard distant gunfire toward the east he was not alarmed. But by the time he had nearly cleared the pass, the faraway musketry had been joined by the deeper rumble of cannon fire, indicating something more than a light skirmish was taking place.

Arriving in Cashtown, Lee checked with General Hill, who was suffering from one of his periodic bouts of illness and clearly out of touch with events. Hill had no idea what all the firing was about, but one of his three divisions (that commanded by Maj. Gen. Henry Heth) was supposed to be investigating reports of Federal horsemen in the town of Gettysburg. He left to find out what was happening, while Lee slowly followed.

Approaching the outskirts of Gettysburg it became apparent that a fight of some magnitude had taken place earlier this day. When Hill appeared with Heth in tow, Lee heard a confused tale of a small scrap against cavalry that had suddenly escalated into a full-blown battle when the Yankee horsemen had been reinforced by veteran infantry. Writing a decade after the war about his handling of the morning fight, Heth, who had a lot to answer for regarding his poor deployments and combat management, chose to put all the blame on Stuart’s absence. “Train a giant for an encounter and he can be whipped by a pigmy—if you put out his eyes,” he declared.

At this moment Lee’s best information came from what he could see with his own eyes. From just behind the Confederate lines spread north to south along Knoxlyn Ridge, he observed a parallel Federal deployment across Herr’s Ridge. Based on the flags displayed and prisoners taken, he was facing one Union corps. At this point approaching midday, he preferred to let combat end. Although Heth’s Division had been roughly handled in the morning fight, the rest of Hill’s Corps was close at hand and not under any immediate threat. The first of Longstreet’s men were transiting the Cashtown Pass and Lee expected that the remaining two divisions from Ewell’s Corps were completing their march via roads north of Gettysburg. There was ample reason to use the rest of July 1 to consolidate his army.

Ewell, however, had altered course when his maps indicated that he could save time by routing his columns through Gettysburg rather than around it. This brought his leading elements into contact with the Union infantry that had bested Heth shortly after midday. Despite specific orders to avoid any major engagements until the army was concentrated, Ewell (who afterward claimed that he believed Hill’s Corps urgently needed the help) pitched into the fight, extending the combat to Gettysburg’s north side where a second enemy corps—the XI Corps—was encountered.

Ewell, however, had altered course when his maps indicated that he could save time by routing his columns through Gettysburg rather than around it. This brought his leading elements into contact with the Union infantry that had bested Heth shortly after midday. Despite specific orders to avoid any major engagements until the army was concentrated, Ewell (who afterward claimed that he believed Hill’s Corps urgently needed the help) pitched into the fight, extending the combat to Gettysburg’s north side where a second enemy corps—the XI Corps—was encountered.

Lee watched as the Federals reoriented themselves to counter Ewell’s advance. Unwilling to stand idly by while one of his corps was engaged, he reluctantly allowed Hill to press the attack. The result was some hard fighting on both the western and northern fronts that eventually compelled the Yankees to retreat through Gettysburg, closely pursued by jubilant Rebels.

Lee rode forward to Seminary Ridge, the ridge closest to the town. There he could observe that the defeated enemy soldiers were regrouping on the high ground of Cemetery Hill just to the south of the town. This would not do, but how to prevent it? Two of Hill’s divisions had taken heavy losses driving the enemy, and Lee did not believe them capable of a further effort this day. Longstreet’s column was too distant, leaving Ewell’s soldiers as the best option.

A series of messages now passed between Lee and Ewell, who led what had been Stonewall Jackson’s old command. Lee appears to have made no adjustment to having a different personality in charge. His trust in Jackson had been implicit. As he said of his late lieutenant: “I have but to show him my design, and I know that if it can be done it will be done.”

Now Lee was giving Ewell the same degree of latitude by suggesting or urging an action, not demanding it, though Ewell, for his part, apparently preferred more specific orders.

Ewell indicated to Lee a willingness to resume the attack, but only if he could get Hill to cover his right flank. Despite having the one unengaged division of Hill’s Corps close at hand, Lee insisted that Ewell would have to act alone. (When questioned on his decision to withhold these 7,000 fresh troops, Lee answered “that he was in ignorance as to the force of the enemy in front,…and that a reserve in case of disaster, was necessary.”) Worried about a possible enemy threat to his own left flank, and with no help offered for his right, Ewell decided to stand pat. In time Lee would fault Ewell for not doing more. Conversing after the war with Cassius Lee, a trusted cousin, he expressed his regret over Ewell’s hesitancy. “[Stonewall] Jackson,” he said, “would have held the heights.”

The night of July 1 was a time for critical decisions. Lee’s original plan to concentrate near Cashtown was discarded. He was inclined to take up a position along the north-south ridges running west of Gettysburg until Ewell was able to convince him that it made more sense to keep his corps as it was, spread across Gettysburg’s northern side. To sweeten the deal, Ewell anticipated that a key piece of high ground (Culp’s Hill) would soon fall into his hands, which would cut off one of the principal roads being used by the Union army. Lee allowed everyone to hold their positions for the night.

He had entered Pennsylvania anticipating he would fight a major battle, and while he may not have planned for it to happen at Gettysburg, he was also realistic enough to understand that a commander can’t expect to choose his arena. He arose early on July 2, half expecting to find that the Yankees had skedaddled. Not only was the Union army still on the high ground, but it was obvious that reinforcements had reached it during the night. Enemy units now occupied a line that stretched southward from Cemetery Hill along Cemetery Ridge.

Lee’s first encounter this morning was with James Longstreet. His First Corps commander proposed that the Confederates break contact in order to swing south to flank the enemy. The prospect of untangling Ewell’s men from Gettysburg’s north side and marching in vulnerable columns while the enemy gathered strength made Lee rule out Longstreet’s option. Although rebuffed in his attempt to change Lee’s mind about attacking the enemy at Gettysburg, Longstreet left their conversation convinced that Lee had not absolutely ruled out a flanking option.

In later years, Southern writers anxious to promote an image of Lee free from any failures of judgment insisted that he had issued Longstreet orders for an early morning attack, which the sulky corps commander ignored. Histories appearing as late as the 1960s accepted this as a matter meriting discussion. Yet it is clear that Lee could not have ordered such an action for July 2. When he awoke that morning, the exact location of the Union army was unknown. Until he could pin that down it would have been irresponsible to mount any offensive. Most modern historians give little credence to the “dawn attack” orders and the officers whose recollections support it.

Before and after speaking with Longstreet, Lee dispatched scouts to identify the Yankee deployments. While waiting to hear from them, he learned that Ewell’s men had not occupied Culp’s Hill. Rebel parties probing the position before dawn encountered Union soldiers in strength. It took Lee until mid-morning to collate his scouting reports. Some came from (presumably) reliable army engineers, others from officers just trying to help. Lee asked questions when the reports were given, but does not appear to have tagged any as questionable or requiring further verification. Time was his greatest enemy now.

Based on what he heard, he believed the Federal line stretched south along the Emmitsburg Road for a relatively short distance, terminating near or at a peach orchard. With Hill’s men still recovering from yesterday’s fighting, and Ewell’s snagged in rugged terrain unsuitable for large-scale offensive operations, Lee decided that his best chance for success was to employ Longstreet’s fresh troops (only two divisions, though; the third was still in transit) to roll up the enemy’s left flank.

On July 1, Lee had allowed less than half his army to become engaged without being able to control the fight or complete the victory. On July 2, he felt he had sufficient strength to do the job and had identified the enemy’s weak point. Unfortunately for Rebel arms, his conclusions stemmed from bad information and his own overoptimistic assumptions.

Lee believed that the Army of the Potomac was still in the process of reaching Gettysburg when, in fact, much of it (including its commander, Maj. Gen. George G. Meade) had arrived or was very close by. Six of the Union army’s seven corps were present—roughly 54,700 soldiers to Lee’s 42,000—though perhaps just four corps would have been immediately visible from the Confederate lines. He imagined that the Federals were dispirited and demoralized when in reality their fighting spirit was at a fever pitch. The enemy position sketched for him was wrong in several important ways. Instead of running along the course of the Emmitsburg Road, the Union forces followed the actual ridgeline, which diverged to the east before terminating at a low hill (Little Round Top), rather than hanging in the air at the Peach Orchard. The attack Lee planned for July 2 would have struck unoccupied ground but for an act of insubordination by one of Meade’s corps commanders who moved off Cemetery Ridge to occupy the Peach Orchard and nearby high ground without orders.

The army Lee was sending into battle at Gettysburg had been patched together in record time. In the short period between receiving permission for the operation and actually beginning it, he had reorganized it from top to bottom. A two-corps force had become a three-corps arrangement, with new officers put in charge at all levels. There had not been time to road test any of the parts and Lee chose to ignore that critical stage of army building. Greatly worried that bad news from Vicksburg would renew calls to disperse portions of his command, he had set off on his most critical campaign of the war with an army whose command-and-control elements had yet to jell. July 2 at Gettysburg would subject this construct to maximum stress.

Lee later described this day’s battle plan: “It was determined to make the principal attack upon the enemy’s left, and endeavor to gain a position [in the Peach Orchard] from which it was thought that our artillery could be brought to bear with effect. Longstreet was directed to place the divisions of McLaws and Hood on the right of Hill, partially enveloping the enemy’s left, which he was to drive in. General Hill was ordered to threaten the enemy’s center, to prevent re-enforcements being drawn to either wing, and co-operate with his right division in Longstreet’s attack. General Ewell was instructed to make a simultaneous demonstration upon the enemy’s right, to be converted into a real attack should opportunity offer.”

While any commander expects there will be differences between what is planned and what occurs, it is sobering to realize how much of Lee’s plan was either mistaken in its assumptions or misunderstood by its participants. Some six hours had passed from Lee’s receipt of the scouting report concerning the enemy’s left flank and until Longstreet actually reached it there had been no updates. It would seem that with Stuart still absent, there was no one other than Lee himself charged with gathering field intelligence. Longstreet emerged from a lengthy, circuitous route (chosen to avoid detection) to find the enemy not just in the Peach Orchard, but positioned farther back to enfilade the flank of any force moving north along the Emmitsburg Road. This required him to commit nearly a full division, 10,892 men, to neutralize the problem and spend precious hours dislodging the stubborn Yankees from the nearby Devil’s Den and the Wheatfield.

Once begun, the energy of Longstreet’s attack was to spread along the line held by Hill’s troops. It was here that clear, effective communication was vital, but Lee became a mere bystander as his orders passed down through Hill’s chain of command and were corrupted in the process. It took skill and experience to know when a demonstration should be converted into an attack. From subsequent events, it is evident that there was no common sense of purpose among Hill’s subordinates. Some brigades advanced in conjunction with a movement to their immediate right, others held back waiting to be called up to support the neighboring advance, while at least one refrained from moving at all. Any cumulative assault power was dissipated as a result, and countless acts of valor wasted. Even though Lee remained close to Hill throughout this day’s actions, there is no evidence he did anything to spur his lieutenant to better prosecute the action.

Communication was no better with the opposite flank. On the far left, Richard Ewell acted with little regard for what was taking place elsewhere on July 2. This despite a personal visit from Lee in the morning, as Longstreet was preparing for his flank march. When Lee departed, Ewell’s orders were unchanged and from appearances he did not display any sense of urgency. The clear inference is that Lee did not convey the importance of making “a simultaneous demonstration” on the Confederate right flank. According to a recent biography of Ewell, nothing is known of his activities this afternoon. The biographer’s best guess is that the general “probably slept.” His infantrymen maintained a desultory skirmishing on the town’s outskirts throughout the day, but otherwise posed no threat. His artillery provided some help. At the time that Longstreet’s cannons signaled the start of his attack on the far right, 16 of Ewell’s guns rolled onto the constricted crest of Benner’s Hill (northeast of Gettysburg) and targeted Cemetery Hill. For a short period the Rebel cannoneers gave as good as they got, but the heavier weight of the Federal counterbattery fire soon exacted a high price from the Rebel gunners.

By 6 p.m., nearly an hour before any of Hill’s brigades became engaged, the firing died down on Ewell’s front. Things became so quiet that George Meade began shifting 7,700 troops from Culp’s Hill to support his battered left. Then, around 9:30 p.m., with the fighting just about finished on Longstreet’s and Hill’s fronts, Ewell threw 7,600 men against Culp’s Hill and the eastern side of Cemetery Hill. The former effort grabbed some empty trenches on the lower slope, while the latter was hurled back after fierce fighting.

Lee, posted near the physical center of the action, was curiously detached from the combat. According to one of the foreign observers accompanying the Rebels, during the afternoon and early evening the general “only sent one message, and only received one report.” An artilleryman positioned nearby noted that his “countenance betrayed no more anxiety than upon the occasion of a general review.” Soon after the combat ended, Lee had to evaluate what had been accomplished this day, yet of his three corps commanders only Hill made a personal report. The other two sent surrogates with summaries that failed to convey a complete picture of their circumstances. Perhaps that in itself should have made it clear that Longstreet and Ewell had their hands full. However, already lining up his sights on July 3, Lee did not read anything into the absence of the two officers whose personal observations should have shaped his planning.

Based on what he saw, what he was told, and what he believed, Lee assessed that “Longstreet succeeded in getting possession of and holding the desired ground….Ewell also carried some of the strong positions which he assailed….” The desired ground was the Peach Orchard, which Lee thought presented his cannons with an elevated platform sufficient to dominate the Yankee lines along Cemetery Ridge. In fact, as Longstreet’s able artillery chief, Col. Edward P. Alexander, had learned firsthand late on the afternoon of July 2, the ground rose again some 40 feet at the Federal main line of resistance, so packing the Peach Orchard with Confederate cannons provided none of the advantages Lee imagined.

Similarly, Ewell’s report suggested he had penetrated the enemy’s principal defensive lines when, in fact, his troops had taken possession of trenches abandoned by the Federals located well down the slope from the hilltop, which was still heavily fortified and stoutly defended. Ewell’s inaccurate information led Lee to conclude that the Confederate Second Corps “would ultimately be able to dislodge the enemy.” With the benefit of hindsight, it now seems clear that the victory Lee was seeking at Gettysburg loomed so large in his thinking that he only processed the pieces of information that would validate his resolve to continue the fight for one more day. Having composed a picture of an enemy army on the ropes, and buoyed by his faith in his men, he determined to press ahead.

“The result of this day’s operations induced the belief that with proper concert of action, and with the increased support that the positions gained on the right [by Longstreet] would enable the artillery to render the assaulting columns, we should ultimately succeed,” he later wrote, “and it was accordingly determined to continue the attack. The general plan was unchanged. Longstreet, re-enforced by Pickett’s three brigades,…was ordered to attack the next morning, and General Ewell was directed to assail the enemy’s right at the same time.”

Also receiving orders was Jeb Stuart, who had reached the battlefield at some point in the afternoon of July 2, well ahead of his troopers, who would not be available for any serious work that day. Lee appears to have passed over Stuart’s belated arrival without comment, although some postwar memoirs manufactured a bit of dialogue to show his displeasure. Speaking of these events some five years in the future, Lee alluded to Stuart’s failure when he allowed that the Gettysburg fight was “commenced in the absence of correct intelligence.”

What was supposed to be a rapid cavalry march to the head of Lee’s infantry columns had been bedeviled by fate and fateful decisions. Despite what Lee and Stuart believed, the Union forces were already moving north when the operation began, forcing the Rebel riders on a wide detour to reach an unguarded Potomac ford. The chance capture of a U.S. supply train outside Washington that same day further upset Stuart’s timetable. He lost valuable time paroling Yankee teamsters and guards, and was then burdened by attaching the slow-moving wagons to his column. There were several brief but sharp encounters with Yankee cavalry and a poor read of the situation by Stuart who, on July 1, closed on Carlisle, Pennsylvania, in a vain effort to connect with Ewell. Compounding his errors in judgment, Stuart then tried to dislodge Pennsylvania militiamen holding the town until early in the morning of July 2, when he at last learned the location of Lee’s army.

Lee arose on the morning of July 3 to find his plans already unraveled. Without waiting for any signal from the opposite flank, Richard Ewell resumed his assaults against Culp’s Hill at dawn. Lee intended for Ewell and Longstreet to launch their attacks “at the same time,” yet nothing in Ewell’s instructions to his subordinates suggested any need for coordination. It would seem that Ewell’s sudden obsession with capturing Culp’s Hill overrode any other considerations. Once again Lee had failed to make explicit the critical part he expected his Second Corps commander to play.

Ewell wasn’t Lee’s only problem lieutenant this morning. When he checked with Longstreet to find out how far along his preparations were, he learned that the officer had spent the night trying to locate a way around the enemy’s left flank, now pegged to the two Round Tops. Lee also discovered, seemingly for the first time, that the two Longstreet divisions engaged on July 2 were in no shape to resume operations. Considering the proximity of his and Longstreet’s headquarters, Longstreet’s failure to inform—and Lee’s failure to discern—this state of affairs again represented a significant breakdown.

It speaks to Lee’s mental resilience and unflagging determination that he immediately cobbled together a new plan. The prospect of calling off an attack never entered his mind. Longstreet and Hill, as well as several subordinate officers and their staffs, now met with their chief to see what resources were actually available. From Longstreet, Lee had Maj. Gen. George Pickett’s fresh division, waiting close by in ready reserve. From Hill came Heth’s Division to join Pickett, backed up by four brigades—two from Pender’s Division, two from Richard Anderson’s—for a total of about 11,800 troops. Selecting Heth’s Division provided a focus for the attack, since it was roughly opposite the Federal center, defended by 6,500 troops.

Much to Longstreet’s surprise, he was tapped by Lee to direct the combined operation, even though Hill had at least as many men committed to the assault. Speaking with a bluntness that perhaps he hoped would recuse him once and for all, Longstreet said: “General, I have been a soldier all my life. I have been with soldiers engaged in fights by couples, by squads, companies, regiments, divisions, and armies, and should know, as well as any one, what soldiers can do. It is my opinion that no fifteen thousand men ever arrayed for battle can take that position.” Nonetheless, Hill’s poor handling of troops on July 1 was still fresh in Lee’s mind, so Longstreet got the assignment.

While preparations went forward, Lee added other elements to the plan to improve its chances of success. He intended to precede the assault with a massive bombardment of the target area involving all the cannons from Longstreet’s and Hill’s corps. With Hill’s guns included in the mix, the Confederates would catch many of the Federal batteries on Cemetery Hill and Ridge in a killing crossfire. He explained this to the Army of Northern Virginia’s artillery chief, Brig. Gen. William Nelson Pendleton, and left him to handle the details.

There was a second part to the artillery scheme, as important as the preliminary softening-up phase. The movement against Cemetery Ridge would initially pass over rolling ground that offered sheltered swales where the men in the advancing lines of battle could duck the enemy fire and realign. Once they reached Emmitsburg Road, however, the men would be fully exposed to cannon fire and musketry at point-blank range.

Read More in Military History Magazine

Read More in Military History Magazine

Subscribe online and save nearly 40%!!!

Lee planned to advance as many batteries as possible with the infantry and have the guns drench the enemy positions with shells just prior to the final lunge. This, he expected, would suppress any Union cannons that managed to survive the opening bombardment and sufficiently cow the enemy infantry. The plan required that Alexander’s batteries be promptly resupplied after firing off their ready rounds during the opening bombardment, another matter left to Pendleton’s attention.

Some historians believe that there was another element to the assault as planned. There is evidence that provisional orders were issued to selected units holding the line for a follow-up advance once the enemy’s line had been breached. Taken in the aggregate, these units constituted a second wave intended to exploit the breakthrough. The responsibility for committing this group rested with Longstreet, who was already an unwilling participant in the attack. Why Lee did not reserve this decision for himself is another of the battle’s unanswered questions.

With the arrangements made, Lee briefly prowled the lines before returning to his headquarters to wait. If the bombardment did its work, if the flanks were protected, and if enough of the artillery advanced with the infantry, Lee felt that his superb soldiers would smash through the Yankee army. He expected that the Federal soldiers would lose their nerve, and he was utterly confident that his men would press the attack all the way to Cemetery Ridge. There was little more for him to do. It was all now in God’s hands.

That the subsequent assault, known as Pickett’s Charge, failed was a major setback to Lee. Afterward he seemed to blame the soldiers involved. In his second official Gettysburg report, he admitted that he might have asked more of his men “than they were able to perform.” To his wife, Lee wrote that his men “ought not to have been expected to have performed impossibilities.” What he seemed to miss in his analysis, then and after the war, were his own failures to ensure that his instructions were carried out.

He might have started with his artillery chief, Pendleton. While Longstreet’s artillery commander, Alexander, knew the game plan, it is clear that his equivalent in Hill’s Corps, Col. R. Lindsay Walker, did not. Numerous Third Corps batteries failed to participate in the bombardment, leaving most of the Federal guns on Cemetery Hill and Ridge free to pummel the infantry wave. Pendleton also neglected to keep the critical ordnance resupplies close at hand, so when the time came for Alexander’s batteries to move forward with the infantry, only a handful had sufficient ammunition to justify making the effort, not enough to make a difference. As Lee had feared, the tract from the Emmitsburg Road to Cemetery Ridge proved to be the killing ground that broke the back of the assault.

Lee refrained from any negative comments about Pendleton’s performance in his Gettysburg reports, while the artillery chief’s narrative makes it seem that every instruction was carried out. Lee appears to have had a soft spot for the West Pointer, who had forsaken the ministry for a military career, even though Pendleton informally acknowledged his inadequacies as artillery chief by granting tactical control of batteries on the battlefield to younger officers of lower rank. The cost for Lee’s personal kindness of carrying the weaker man along was dear.

It is also worth noting that while Lee waited at his headquarters for Longstreet’s attack to begin, he made no effort to coordinate with Ewell. By the time Pickett’s Charge began, Ewell had shot his bolt on Culp’s Hill and was no longer threatening that enemy flank. Lee recognized on the evening of July 1 that it would be a stiff challenge to effectively integrate his Second Corps operations with the rest of the army. Once he agreed to let Ewell remain on the north side of the town, it was incumbent on him to make certain Ewell knew his part. From the evidence in hand, Lee failed to do so.

Jeb Stuart’s role on July 3 is also the subject of much speculation. His instructions for July 3, as recollected by his adjutant, were to “protect the left of Ewell’s corps…observe the enemy rear and attack it in case the Confederate assault on the Federal lines were successful…[and] if opportunity offered, to make a diversion which might aid the Confederate infantry.” While accomplishing the first, Stuart was unable to do more. His efforts to advance were checked in fierce fighting over what is today known as the East Cavalry Battlefield. It should be stressed that his orders to attack the enemy rear were conditioned on a successful infantry breakthrough.

The failure of the assault against Cemetery Ridge marked an end to Lee’s offensive designs. After personally helping to rally the defeated men from Longstreet’s and Hill’s corps, he planned a withdrawal from Pennsylvania that began on the night of July 4. Even when blessed by a timid pursuit from Union forces, the march was staggered by bad weather and the burden of carrying so many casualties. A good estimate of Lee’s losses is 22,874 killed, wounded, or missing, more than a third of his force. Not until July 14 would the Army of Northern Virginia be safely across the Potomac River, ending the campaign.

Lee’s performance at Gettysburg was far from masterful. Time and again he failed to impress upon his key lieutenants the full intent of his orders, and at critical moments in the battle’s second and third days he crafted offensive plans based on misinformation. On July 1 he was reluctant to finish the fight and refrained from using a readily available reserve to assist Ewell in taking the high ground that would prove central to the Union success. He also permitted his Second Corps to remain in a position that greatly compounded the normal difficulties of command and control. On July 2 Lee based the day’s battle plan on faulty intelligence and then kept hands off once the action began. His position near the Confederate center put him at the critical boundary between Hill’s and Ewell’s corps, yet he took no proactive steps to ensure a maximum effort was mounted. On July 3, Lee’s determination to strike a blow led to a compromise plan that needed careful management to succeed, oversight that was tragically absent.

There is no evidence that Lee ever marked the irony that Vicksburg surrendered to Union forces on July 4. Even though he afterward insisted that the Gettysburg campaign had achieved most of its goals (resupply of his army and deterring Federal incursions into Northern Virginia for the harvest season), Lee submitted his resignation on August 8, citing health issues and public discontent over the battle results. President Davis promptly rejected the request, leaving Lee in command of the Army of Northern Virginia to the war’s end. In another note to Davis, Lee observed: “I still think if all things could have worked together [then victory] would have been accomplished. But with the knowledge I had then…I do not know what better course I could have pursued.”

In the few years left to him after the war, Lee rarely commented on his experiences in Confederate service. When he did talk about some of the battles he fought, Gettysburg figured high on the list. One gets the impression that he was still struggling to understand how that one got away from him. Speaking about it with Washington College faculty member and former Army of Northern Virginia officer William Allen, Lee once more voiced his disappointment with Jeb Stuart, who “failed to give him information, and this deceived him into a general battle.” Looking back, he told Allen he was certain that “victory would have been won if he could have gotten one decided simultaneous attack on the whole line.” The closest Lee would come to acknowledging the part his misconceptions and poor communication played in losing the battle was an admission to a confidant in 1868 that his defeat in Pennsylvania “was occasioned by a combination of circumstances.”

Perhaps the most unguarded expression of Lee’s feelings about the battle came at the end of July 4. It was late and he had been active all day organizing the withdrawal—heavy work for an older man—and was feeling the effort. When he met with the officer charged with escorting the train of the wounded, who was expecting orders, Lee instead made him audience to a rare monologue. With the anguish of a master designer who has seen one of his finest constructs fall, Lee let down his guard. “Too bad! Too bad!” he exclaimed. “Oh! Too bad!”

Featured Article

Lee to the Rear

‘Lee to the Rear!’

A Texas private’s long-forgotten account of Robert E. Lee’s brush with death at the Battle of the Wilderness.

On May 6, 1864, following a day of inconclusive fighting in the Wilderness, General Robert E. Lee watched at the edge of the Widow Tapp’s field as the Army of the Potomac’s II Corps drove westward on the Brock Road toward the vulnerable right flank of A.P. Hill’s Corps. Just as a Union breakthrough seemed imminent, Lee spied the approaching van of Lt. Gen. James Longstreet’s Corps. The famed Texas Brigade of the 1st, 4th and 5th Texas, and the 3rd Arkansas, commanded by Brig. Gen. John Gregg, was near the front of that gray column—and they may very well have saved Lee’s life that day. What happened in the Widow Tapp’s field could have altered the war’s course.

As the Texans reached the battlefield, Lee attempted to lead them into battle. But the men refused to let him take that risk. They forcibly led Lee and his horse Traveller away from danger, then joined the rest of Longstreet’s soldiers in stemming the Federal tide.

The “Lee-to-the Rear” incident has long been regarded as one of the most dramatic episodes in the storied history of the Army of Northern Virginia. Over the years, various eyewitness accounts of the episode have made it into print, dozens of historians have analyzed the meaning of the moment and numerous artists have interpreted the chaotic scene. The recently discovered account excerpted here, first published in Texas Magazine in January 1912 by James H. Cosgrove, a 23-year-old private in Company C of the 4th Texas, sheds new light on the incident. No previous account has made it clear that a man was killed while leading Traveller to the rear, illustrating how close the South came to losing its best general.

As Longstreet’s men approached the Wilderness’ smoky thickets on the morning of May 6, they lagged far behind the schedule that Lee had hoped for. In this instance, unlike at other controversial moments during the war, Longstreet does not deserve blame for the tardiness. The men had moved steadily most of the night—“fast and double quick as much as we could,” one of them wrote. Another called the pace “a turkey trot.”

Near Parker’s Store, not far west of the front lines, two approaching divisions converged and had to share the Orange Plank Road corridor. General Joseph B. Kershaw’s men deployed to contest the virtually unchecked enemy advance on their right (south) of the Plank Road: Georgians under General Goode Bryan; Mississippians of General B.G. Humphreys’ Brigade; and Kershaw’s old command, now led by Colonel John W. Henagan.

Kershaw’s doughty warriors restored order and bought time for the Texans to arrive at the edge of the Widow Tapp’s field. As the Texas Brigade turned left off the Plank Road and formed along the western edge of the widow’s three-dozen cleared acres, Private Cosgrove was in the ranks, clutching his rifle. His description follows:

What a beautiful morning that was as we met in ascending a long, red Virginia hill….A clear, majestic sun, dispelling lazy fragments of fog, warmed with its beams the chills of the past night….Not a sound of all the first day’s fighting had reached us. We had moved with the rapidity of a forced march from Gordonsville, coursing our way through deep woods….

I am to tell of how I saw General Lee, as he rode at full speed across the front of our brigade, then leading the division, in column of attack…in support of the Canton, Mississippi, battery, firing desperately into the pine thicket a few hundred yards away. These thickets were crowned with the tops of Federal battle flags, showing a large force, which was further evidenced by a musketry fire withering in the extreme….

In this mighty din, with Field’s and McLaw[s]’s divisions…panting in leash, General Lee, accompanied by a single courier—a lad just beyond his teens…Brown, yet living near Canton, Mississippi—spurred up to the battery commander….Around me were dead and falling men and horses and above me the incessant and deafening hiss of a storm of bullets….Near me, lying on a rubber blanket, was the body of a handsome young lieutenant of the artillery company….His features, beautiful in death, will be with me always….Here it was that Lee rode out to lead his army in a charge for the first time!

We were called to attention, and, in moving forward, “arms at right shoulder, guide center,” I saw General Lee somewhere near the center of the brigade front formation, when the cry went up, “Lee to the rear! The general to the rear!” and the brigade halted….

Ordnance Officer Randall of Rusk, Texas, seized General Lee’s bridle and was killed dragging his horse back to the rear. The enemy was at point blank distance and the firing upon us was very, very heavy. Then came that trumpet voice of General Gregg, our brigade commander: “Men, the eyes of your general are upon you; forward, and give them hell!” Into that zone of death headlong went the brigade.

Coming out wounded, some twenty or thirty minutes later, I saw General Lee near where Lieutenant Randall had fallen, and as I passed with a group of others hurt, I heard him say: “Men, everything is prepared for you at the field hospital…..” And the wounded, some of them even unto death, cheered him.

To gaze upon a beloved commander at a moment and upon an occasion which would be particularly marked in history is reserved for but comparatively few, and the impression will be lasting.

This vision at once suggests itself to me when I hear General Lee’s name mentioned, and it is the most vivid mental picture I retained of the general, or of any event of the war coming under my personal observation.”

The details reflected in Cosgrove’s account stand up to investigation. Lieutenant Whitaker P. Randall, acting ordnance officer on General Gregg’s staff, was in fact killed on May 6. He was only 24. The Texas Brigade suffered nearly 600 casualties—including Cosgrove, who was wounded—that day out of a total strength of not much more than 800. Some sorrowing comrade must have marked Randall’s burial spot, because the ordnance officer’s remains were eventually interred in the Confederate Cemetery on Washington Avenue in Fredericksburg, where a marker spells his name almost correctly.

Read More in Civil War Times Magazine

Read More in Civil War Times Magazine

Subscribe online and save nearly 40%!!!

James Cosgrove had enlisted at Owensville, Texas, on April 19, 1861. He apparently crossed into Texas from Louisiana for the purpose, as the 1860 census did not enumerate a single Cosgrove anywhere in Texas. After the war, Cosgrove returned to Louisiana. He was living in Shreveport in 1913, and as late as 1915 an inquiry about his service went to the Louisiana pension board. His widow, Julia A. Cosgrove, later applied for a pension based on James’ wartime record.

Robert K. Krick is well known for his dogged research, which uncovers gems such as Cosgrove’s account.