Newly opened venue breaks new ground in telling stories of the people who lived and died in the nation’s seminal struggle

[divider]ENTERING THE NEW American Civil War Museum at the historic Tredegar Iron Works in Richmond, Va., the first thing you notice is the color. Here are large photographs of familiar and unfamiliar faces—Jefferson Davis, Abraham Lincoln, Harriet Tubman, enslaved workers in a field, a Native American soldier, and others—covering the walls leading to the museum’s permanent exhibit. Unlike the black-and-white images we’re used to, these portraits have been colorized. We see different shades of skin, tired faces with crow’s feet and dark circles, and the blues, greens, and browns of eyes. Instantly, these once-distant personages become more lifelike and three-dimensional, as if they could be one of us, and that’s entirely the point.

[divider_flat]The result of the 2013 merger between the Museum of the Confederacy and the American Civil War Center at Historic Tredegar, the new museum has emerged at a significant time and place. Here, in the city that was once the Confederate capital and in the state that saw a deadly 2017 riot around the proposed removal of a Robert E. Lee statue, the museum is well-positioned to wrestle with ongoing discussions about how the war should be memorialized and interpreted for future generations. “We want to get away from mythmaking and back to history,” museum CEO Christy Coleman said at a special event before the museum’s official May opening. “We’re bringing together different narratives. It’s an American story that impacted people from shore to shore.”

The new museum encloses the brick ruins of the historic iron works—a major supplier of artillery and munitions for the Confederacy—in a modern glass structure designed by Richmond architects 3North, with space for both permanent and temporary exhibitions, an artifact examination room, a sitting area, and gift shop. It anchors a larger campus along the historic James River that includes the iron works’ former Pattern Building, used as the main visitor center for the Richmond National Battlefield Park, and the former Civil War Center, which will now be dedicated to special events and meetings.

On its face, the permanent exhibit, titled A People’s Contest: Struggles for Nation and Freedom in Civil War America, goes through the standard war chronology, from the growing discord around slavery to major battles and leaders and then, finally, the postwar constitutional civil rights amendments. But the museum also breaks new interpretive ground through its multiple viewpoints, through the selection and display of about 550 artifacts, and through the often-surprising juxtapositions it poses. (The museum’s second floor also includes space for temporary exhibits, the first of which is called Greenback America, an examination of how paying for the Civil War transformed American banking, trade, and currency.)

If the first thing you notice upon entering the museum is the colorized imagery, the second thing you might notice are the angles—triangles and asymmetrical shapes that form a leitmotif throughout the museum, including even the screen of the theater. Created by Kentucky-based exhibit design firm Solid Light, the graphics are a bold representation of the fragmented nature of the nation during wartime, but also of the war’s many stories. The triangles represent the shards of artifacts, the broken families and bodies of the enslaved and of civilians, and the incomplete narratives that generations have often clung to about the war.

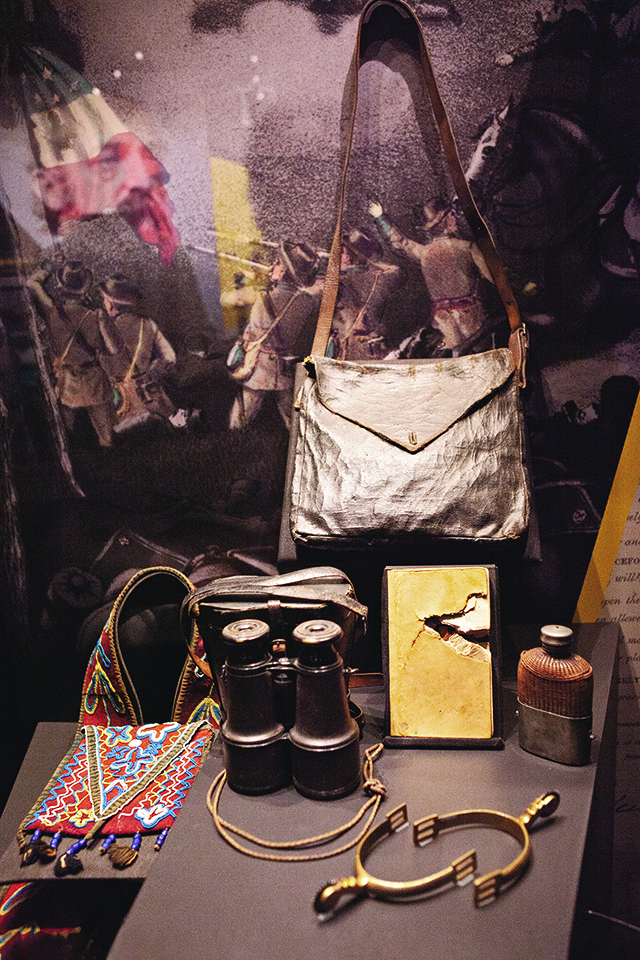

Carrying the idea further, early in the exhibit we see a reproduction of the Henry House, a home that was demolished by artillery fire during the First Battle of Manassas and whose owner, Judith Henry, was mortally wounded. In the museum, jagged wooden shards of the exploded house are suspended above our heads like the sword of Damocles. In the same part of the exhibit, other artifacts are encased beneath visitors’ feet, including soldiers’ gloves, field glasses, and a bayonet, almost a stylized version of an archaeological excavation site. The war’s cost to people and property is not relegated to a side story, but is front and center, above and below, literally.

Each paneled section of the museum includes a small infographic, accompanied by a slash, that illustrates the war’s many fault lines. For a display about slavery, the choice is “Seize Freedom/Risk Danger.” For a section on the machinery of war, the paradox is “Made by Americans/To Fight Americans.” This kind of unexpected juxtaposition continues throughout the museum. We see a standard-issue Confederate battle flag, but the fine print tells us that it is one that Robert Todd Lincoln kept as a souvenir at war’s end. Elsewhere, a circa-1869 gilt-framed painting of Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson on horseback, titled “The Last Meeting”—once prominently hung at the Museum of the Confederacy—is now placed opposite a large colorized portrait of eight African-American members of Virginia’s postwar General Assembly. That image is further juxtaposed with a Ku Klux Klan robe and hood, a haunting image of white supremacy from the past and present. You can’t tell one story without also telling another, the museum seems to be saying.

Visitors move through a series of spaces that feel distinct from each other and yet logical. A section on slavery is particularly arresting, as images of enslaved and freed people are projected onto a piece of homespun cloth that hangs around a set of chains. Depending on the narration and lighting, the images or the chains or the cloth visually come to the forefront, weaving a complex and moving tale. In a case nearby are a pair of shackles, further underscoring the human toll of a tragic institution. Elsewhere, visitors go into a “cave” that is meant to evoke the caves in Vicksburg, Miss., where civilians hid during the siege of that city. You can also pass between narrow walls and learn about places such as Andersonville and Libby prisons, where thousands of soldiers died of disease.

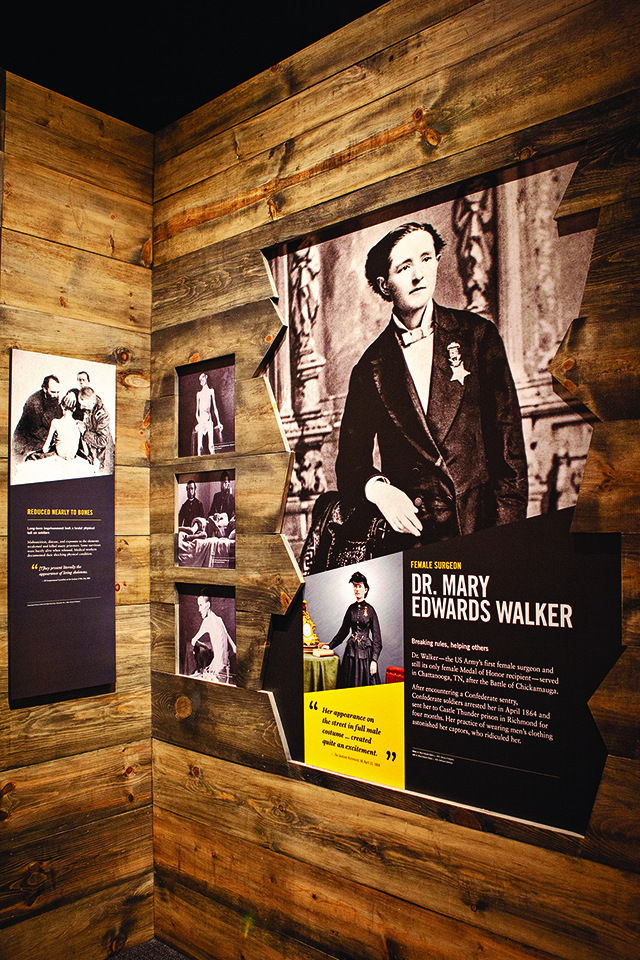

Led by curator Cathy Wright, the museum has put on display a fascinating collection of artifacts that range from the usual suspects to some unexpected treasures. We see a surgeon’s case of scalpels and knives, multicolored ribbons from veteran reunions, daguerreotypes, antique pocket watches and housewares, and rifles and sidearms—all worthy of inclusion in a comprehensive Civil War museum. But here, too, are unusual items that people might want to pore over, not just because of their novelty but because they broaden comprehension of the war’s impact: rose-shaped earrings and a matching brooch carved in bone by a captive Union soldier at Libby Prison; a colorful red, yellow, and blue bandolier worn by a Native American Confederate; and a filigreed sewing machine that mended uniforms from the home front, among many other items.

Just as significantly, this exhibit is populated by a far broader range of people than we’re used to seeing in a Civil War museum. Through quotes, diaries, letters, imagery, and interpretive text, we’re introduced to dozens of individuals who put a face on the Civil War, including Union spy Elizabeth Van Lew; Julia Ann Mitchell and Frederick Coggill, a couple who faced divided loyalties when war broke out; and Medal of Honor winner Sgt. William H. Carney of the famed 54th Massachusetts—alongside more familiar names such as Lee, Grant, Douglass, Tubman, and so on. “The one element that moves me is the overall visual vernacular of the show [with the colorized images],” Coleman said. “There’s something powerful about looking someone in the eye and seeing blue or a particular shade of brown.”

Shedding light on more people, of course, doesn’t take light away from those major figures, both North and South, who should rightly be studied. But it broadens the narrative and allows more of us to see ourselves in that narrative, to imagine what we’d do if we ever found ourselves so divided again. During the Civil War, the museum says, we broke not just in half, but into pieces. Have those pieces all been mended together? The museum leaves that question unanswered.

Kim O’Connell writes frequently for Civil War Times. She is based in Arlington, Va., and has degrees in both literature and historic preservation.