The Greek cities of Asia Minor tried mightily to free themselves from Persian subjugation. But their rebellion ultimately backfired.

On a spring night in 498 bce, spiky tongues of orange and yellow flames darted high into the Anatolian sky. By morning, the ancient city of Sardis would be a smoking pile of ash and corpses. Even the Temple of Cybele, the revered mother goddess of Asia Minor, had been destroyed. The raging inferno was the work of the Ionians—the Greeks on the western shores of Asia Minor and its nearby islands. They had revolted against Darius I, the Great King of Persia, and had come to Sardis to strike a blow for their freedom. Instead, they set in motion a horrific disaster.

For more than four decades, Persian kings had lorded over the troublesome Ionians. Insular and argumentative, the Ionians zealously sought to preserve the 12 cities of their “cultural league.” Chief among these was Miletus, at the mouth of the Maeander River on the southwestern coast of Asia Minor. The Milesians were renowned for their love of philosophy, science, and the arts, unlike their more warlike neighbors. Milesian traders, who were among the first Greeks to use writing and coinage, established dozens of colonies on the Black Sea and as far away as Egypt and Italy.

Of the major cities on the Ionian mainland, only Miletus had avoided being annexed by Croesus, the king of Lydia. But then Persian king Cyrus I defeated Croesus in the Battle of Thymbra in 547 bce and captured Sardis, the Lydian capital, after a 14-day siege. During the campaign, Cyrus appealed to the Ionians for aid, but they remained loyal to Croesus. After Croesus’s defeat, the Ionians offered to transfer their allegiance to Cyrus on the condition that they could maintain the same relative autonomy they had enjoyed under Croesus. But Cyrus understandably declined, conquering the Ionian cities and installing subsidiary rulers, called tyrants, to control them. The new arrangement rankled the proud Ionians, though they remained reasonably docile for the next half century.

In 513 bce, Darius, who had overthrown Cyrus’s successor nine years earlier, launched an ill-fated punitive campaign against the nomadic Scythians—Persia’s first incursion onto European soil. His target was land they controlled adjacent to the Black Sea. The Scythians, renowned for their horsemanship and skill with the bow and arrow, stymied the Persians by refusing to stand and fight. Instead, they adopted a scorched-earth strategy that denied the Persians much-needed supplies and remounts.

Frustrated by his inability to force the Scythians to stand and fight, Darius had halted his pursuit and begun retracing his path home to Persia. Waiting nervously at the Danube River, not far from the Black Sea, were some of the Ionian tyrants and their men. Earlier, Darius had charged them with protecting the pontoon bridge that he had thrown up over the river so that he and his army could cross back safely. The Ionians had dutifully waited for him, week after week, with mounting anxiety. He was now long overdue.

While the Ionians waited, the Scythians rode up to the river and urged them to destroy the bridge. The Persians would then be trapped on the northern side of the Danube, where the Scythians promised to crush them. Some of the Ionian tyrants liked the idea, even though it was pure treason. The Persians, after all, had long smothered Ionia. Miltiades, an Athenian tyrant of the Hellespont, the narrow strait to the northwest, urged his comrades to betray Darius. One prominent Ionian, however, refused to listen to such talk. Histiaeus, the tyrant of Miletus, reminded the others that they owed their positions of power to Darius, not the Scythians, and that at any rate they would have to live with the Persians—and the consequences of their decision—when they returned home. The tyrants quickly reconsidered their flirtation with treachery.

Histiaeus and his men then began to tear down the northern end of the bridge—but only to trick the Scythians into thinking that he meant to do what they had requested. He then convinced the Scythians to search for the Persians. Meanwhile, Histiaeus and the other Ionians waited for Darius and his army—what was left of it—to show up. When the Persians finally arrived at the Danube one night in 512 bce, the Ionians sent boats to ferry them over.

Darius rewarded Histiaeus for his loyalty by permitting him to build and fortify a new city, Myrcinus, on the Strymon River in Thrace, thereby arousing the jealousy and suspicion of other Ionian tyrants. Megabazus, one of Darius’s top generals, who went straight to the king with his fears. “Just think of what you have done,” he told Darius. “You gave a dangerously clever Greek permission to found a city for himself in Thrace, where timber is abundant for construction of ships and oars, where there are also silver mines and multitudes of Greeks and non-Greeks. As soon as these people find a leader, they will follow his orders day and night.” Histiaeus, Megabazus argued, now had everything he needed to become a potentially threatening warlord on a remote frontier of the Persian Empire.

As a precaution, Darius cannily invited Histiaeus to become one of his senior advisers in the imperial capital of Susa, in Iran. Histiaeus initially considered the summons a great honor, little suspecting that it was designed merely to keep him far away from Ionia.

While Histiaeus was still the official tyrant of Miletus, his cousin and son-in-law, Aristagoras, became its de facto ruler. In 500 bce a contingent of exiled noblemen from the island of Naxos came to Aristagoras, seeking aid to restore them to their homeland, from which they had been driven by their own people. The Naxian exiles claimed xenia, or guest-friendship, with Histiaeus. Xenia was a pact, ordinarily between noblemen of different city-states, that entailed mutual obligations of hospitality and assistance. Among the Greeks this bond was taken very seriously.

Seeing an opportunity to boost his power and perhaps even gain control of the island himself, Aristagoras pledged to attack Naxos. Lacking sufficient forces of his own, he went to Sardis to seek aid from Artaphernes, the Persian satrap (governor) there. The Naxian exiles had empowered Aristagoras to offer Artaphernes money in exchange for his military support. In addition to this financial enticement, Aristagoras suggested to Artaphernes that he might acquire some of the other Greek islands that dotted the Aegean. Aristagoras asked for 100 triremes, the triple-tiered oared warships that represented the zenith of contemporary naval design, and Artaphernes, tantalized by the prospect of

conquest, pledged twice that number. After Darius also approved Artaphernes’s plan, a huge army was assembled under the command of Megabates, a cousin of Artaphernes, and boarded the triremes for transport to Naxos.

Aristagoras and Megabates, however, began quarreling before the expedition had even set out. Neither man was willing to accede to the other’s command, and Aristagoras further inflamed the situation by intervening when Megabates tried to discipline one of the Ionian commanders for failing to post watch on his vessel. In the spring of 499 bce Aristagoras’s fleet, approaching the island, found it locked up tight against an assault. The Persians launched their siege anyway. After four months, having run through all their provisions, they finally gave up and sailed away.

Aristagoras was now in a very bad position. He had failed to conquer Naxos as he had promised, and his finances had been gutted in the attempt. To deflect blame, Aristagoras spread the false story that Megabates had warned the Naxians about the invasion. (More probably, a trading ship had brought news of the approaching invasion to the island after resupplying the standing Persian fleet at Chios, some 70 miles away.) Aristagoras feared that Darius, on hearing the rumors circulated by Megabates, would strip him of power at Miletus. With his once bright future dimming by the day, Aristagoras began to cast about for a way to save himself.

Around the same time, Aristagoras’s long-absent father-in-law reentered the picture. Histiaeus, chafing in his gilded cage in Susa, wanted to get back to Miletus. The best way to accomplish this, he thought, was to secretly spark a revolt in the city that would cause Darius to turn to him to put it down. But how to instigate such a revolt? Because any message might be intercepted by Darius’s agents before it reached Miletus, Histiaeus had to be creative. He had the head of his most reliable slave shaved and the secret order to revolt tattooed on the slave’s scalp. Histiaeus then waited for the slave’s hair to grow back and cover the message. The slave then set off for Miletus, with orders to tell Aristagoras to shave the messenger’s head when he arrived.

Aristagoras received the secret message as planned, but he was already plotting his own scheme for rebellion. He convinced some leading Milesians to support the revolt against Persia and, in the meantime, pretended to come out in favor of democracy. He called for the other cities of the Ionian League to depose their own tyrants and install governing boards of generals, who would in turn report to him. It did not seem to occur to anyone that the new arrangement would merely place Aristagoras at the head of a new, enlarged tyranny. Nevertheless, inspired in part by the Persians’ intolerable practices of enslavement, forced deportation, and even the concubinage of Ionian women, the league’s members followed Aristagoras into open revolt.

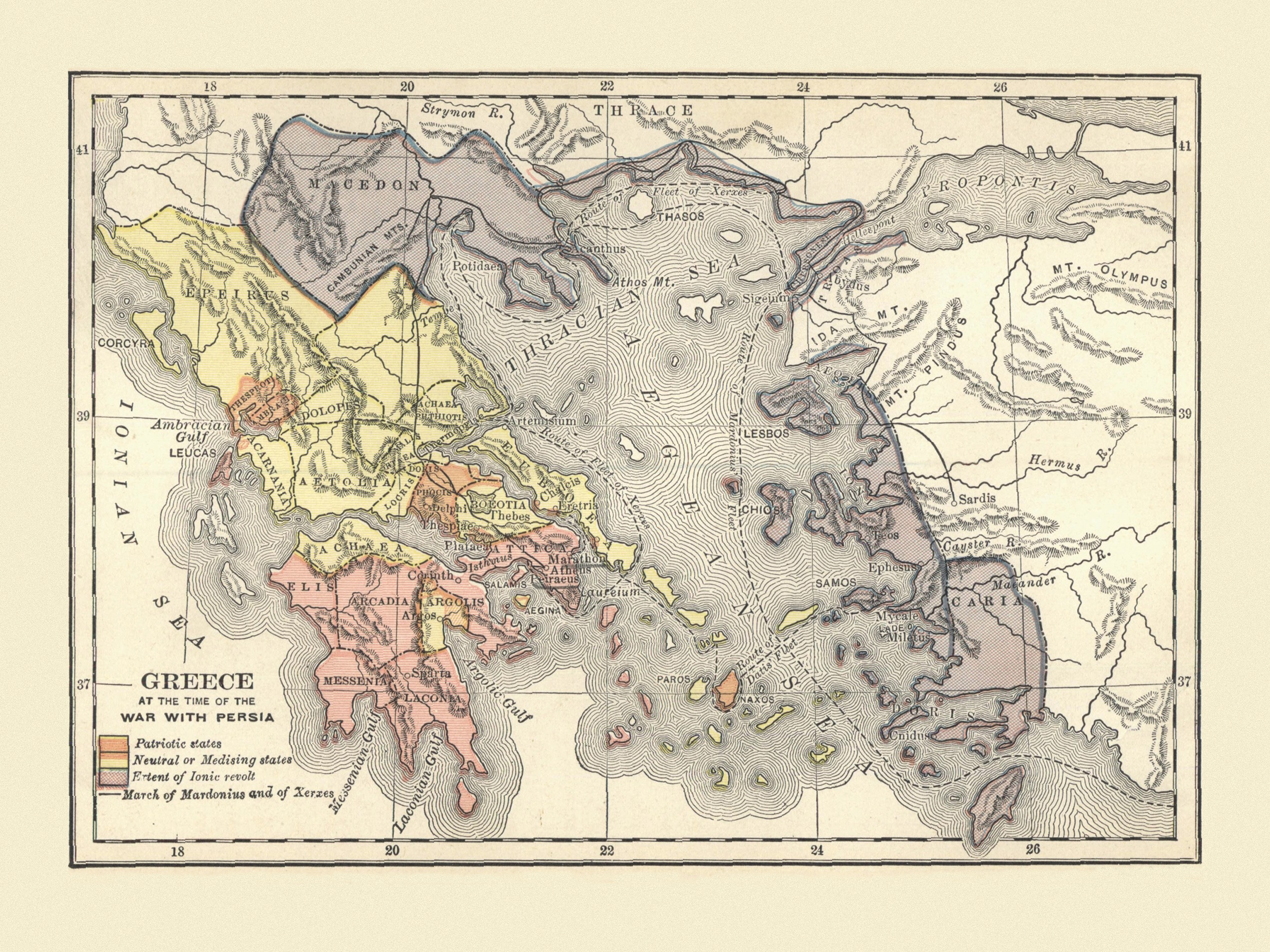

Aristagoras sailed to mainland Greece to drum up support for the revolt, but he had no success in persuading the typically warlike Spartans to aid the Ionian cause. To impress Cleomenes, the king of Sparta, Aristagoras brought with him an engraved bronze map of the world, using the impressive new visual aid to show Cleomenes the locations of the various rich Persian client states. According to the Greek historian Herodotus, Aristagoras told the Spartan king that “the people who live in those lands possess more in the way of assets than the entire population of the rest

of the world.” All this, said Aristagoras, could belong to Cleomenes if only he would “cease fighting for small patches of valueless land with narrow borders” and turn his attention to Persia. While Cleomenes liked the idea in the abstract, he quickly soured on the plan when Aristagoras admitted that it would take three months to march from the Ionian coast of Asia Minor to Susa—some 1,600 miles. According to Herodotus, even the king’s 8-year-old daughter saw the folly of such a plan, warning her father that “your guest-friend is going to corrupt you if you don’t get away from him,” so Aristagoras left Sparta empty handed.

Aristagoras next went to Athens. The Athenians had recently overthrown their own tyrant, Hippias, and reconstituted themselves as a democracy; they were primed for action against Persia. Hippias had tried and failed to reclaim power with the help of Sparta, Athens’s traditional rival, fleeing to Sardis, where he attempted to convince Artaphernes to support another attack on Athens. The Persian satrap declined to actively take part, but he instructed the Athenians to reinstall Hippias as tyrant. They refused, which amounted to an act of war against Persia.

Aristagoras, addressing a crowd of 20,000 Athenian citizens, played on tribal loyalty, reminding his listeners that Miletus had been settled—at least in part—by Athenian immigrants. He also stressed the purported inferiority of the Persian infantry. Finally, Aristagoras emphasized that he had instituted democracy in Miletus and helped other Ionian cities throw off their tyrants. Athenian-style democracy was on the rise everywhere, he implied, conveniently leaving out his own power grab. He received a good response. Apparently it was “easier to deceive a crowd than a single man,” Herodotus noted dryly.

The Athenians agreed to lend military support to the uprising, chiefly in the form of 20 triremes. “These ships,” Herodotus wrote, “turned out to be the beginning of evils for both Greeks and barbarians.” The Athenian squadron arrived at Miletus in early spring 498 bce, and with it came five additional triremes from Eretria, a city on the island of Euboea. Aristagoras proceeded to send the Ionians, Athenians, and Eretrians to Sardis while he remained safely behind Miletus’s stout walls.

The expedition started out well. The rebels sailed north to Ephesus, left their ships behind at the port of Coressus, and marched inland, following the Cayster River to Mount Tmolus. Sardis was sited on the spur of the mountain overlooking the Hermus Valley and the western terminus of the Persian royal road. The Ionians seized the lower city without a fight. Artaphernes, caught entirely by surprise, retreated to the high ground at the acropolis with a substantial body of soldiers.

A fire, probably set intentionally, although Herodotus implied it was accidental, rapidly spread through the reed- and straw-thatched houses. The townsfolk, surrounded by the blaze, fled to the banks of the Pactolus River, source of the gold dust that had given rise to the legendary wealth of the former Lydian king, Croesus. The massive fire kept the Ionians from plundering Sardis. In a do-or-die show of courage, the city’s inhabitants organized themselves into

a semblance of a fighting force. The serendipitous arrival of Persian reinforcements caused the Ionians to hurriedly withdraw from Sardis to Mount Tmolus, where they watched the flames rise high into the night sky. By morning nothing was left of the city but smoldering ruins. Particularly galling to the townsfolk was the destruction of the famous temple of Cybele, principal goddess of the Persians.

The Ionians began heading back to their ships without any loot. As news of the attack on Sardis spread rapidly across Asia Minor, the Persians mounted a swift counterattack, with cavalry pursuing the slowly retreating Ionians. When a report of the burning of Sardis reached Darius, the king called for his bow. Then, notching an arrow and shooting it skyward as an offering to the supreme sky god Ahura Mazda, the king uttered a solemn vow: “Let it be granted to me to punish the Athenians.” To etch the vow in his consciousness, he instructed a servant to attend him each night at dinner and repeat the phrase: “Master, remember the Athenians.”

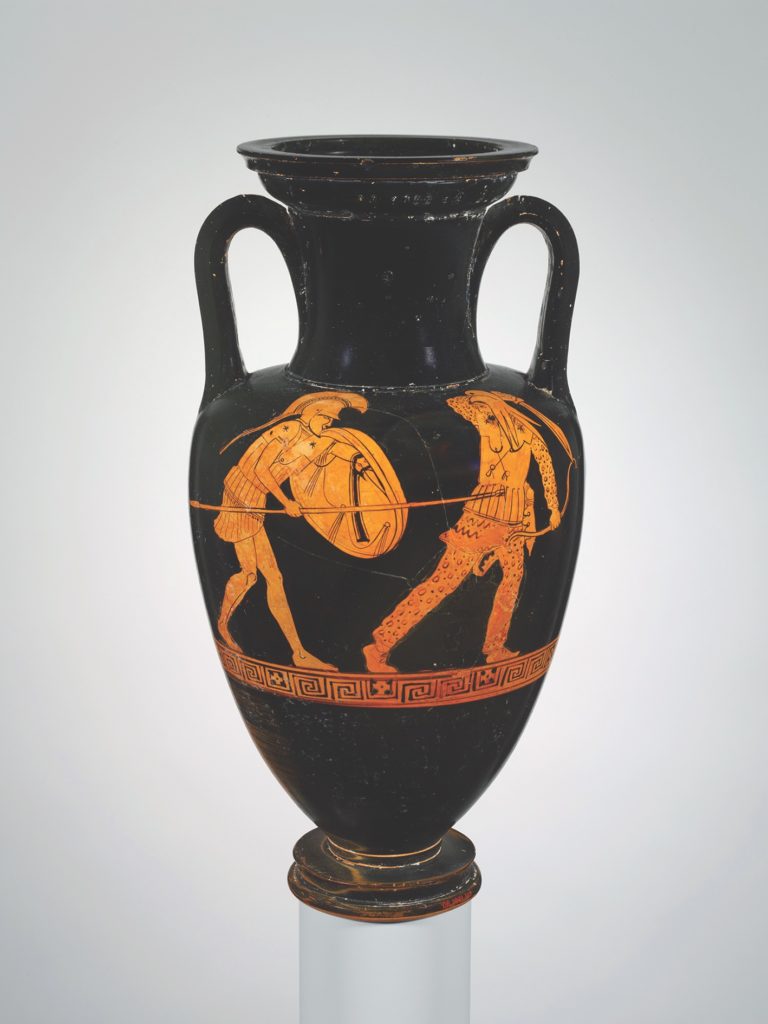

Three of Darius’s sons-in-law led the pursuit. After a furious chase the Persians caught up to the Ionians just outside Ephesus, a city on the Aegean Sea some 60 miles from Sardis. The Ionian hoplites—infantrymen with bronze helmets, reinforced linen cuirasses, round shields, and iron-tipped spears—formed a battle line, shoulder to shoulder, shields locked, but they were no match for the Persian juggernaut. The Persians, in quilted corselets and bronze helmets with towering horsehair crests, were masterful horsemen. They hurled their javelins at the stationary Ionian phalanx or charged it with their spears, while mounted archers showered the Ionians with arrows. Overwhelmed by the vengeful Persians, many hoplites perished on the battlefield.

Their army shattered, the Ionians straggled back to their home cities, any prospect of freedom from the Persian yoke bleaker than before. The Athenians, in turn, abandoned their erstwhile allies and returned to the Greek mainland, resolved to take no further part in the revolt, despite Aristagoras’s repeated pleas.

Although the burning of Sardis was a catastrophe for all involved, the Ionians continued their revolt against their Persian overlords, and in 497 bce the Greeks of Cyprus and the non-Greeks of Caria, in southwestern Asia Minor, joined them. They, too, wanted Persian rule to end. That same year several Greek cities of the Hellespont, including Byzantium, also entered the fray. With a sudden rebellion spreading in the west, Darius turned to the one person he thought could end it: Histiaeus. Receiving the king’s permission to return to Miletus, Histiaeus quickly left Persia for good.

A Persian counteroffensive was already underway. A fleet composed mainly of ships from Phoenicia crossed from Cilicia in southern Asia Minor to rebel-held Cyprus. The troops, led by Artybius, a Persian commander, disembarked and advanced on the coastal city of Salamis, crushing a hastily assembled force drawn from several Cypriot cities.

Aided by the desertion of two contingents of Ionian charioteers, the Persians gained the upper hand, killing Onesilus, the king of Salamis, in the process. The loss negated the naval victory that the Ionians, who had contributed their warships to the defense of Cyprus, had scored the same day against the Phoenician fleet. Judging the battle for Cyprus a lost cause, the Ionians sailed home, leaving the Persians to begin the bloody process of breaking the other rebellious Cypriot cities.

It was a grinding, brutal campaign. Soli, a walled city on the northern coast of Cyprus, held out against a siege for more than four months, falling only after the Persians had undermined its walls. At Palaepaphos, on the west coast, the Persians overcame the city’s walls—while under constant attack—by constructing a large siege ramp from soil, tree trunks, stones, and even nearby statues and altars. Though the Palaepaphians tried to collapse the ramp with four countermines, the city fell, and the defenders’ slingshots were no match for the Persians’ bows and arrows. Within a year the Persians had reclaimed all of Cyprus.

In 496 bce, in southwestern Asian Minor, the Persians routed a rebel army along the Marsyas River in breakaway Caria. The Carians made a good showing but were defeated by an enormous number of Persians. Although the Carians lost 10,000 men to the Persians’ 2,000, they received reinforcements from Miletus and fought another battle in Caria, at Labraunda. Again they were defeated. Still the plucky Carians would not give up, and in a third engagement, at Pedasus, they ambushed a Persian force and inflicted heavy losses on the king’s troops.

Despite the setback at Pedasus, the Persians were relentless, and as they continued to rack up victories, the Ionian revolt crumbled. Artaphernes invaded Ionia, capturing Clazomenae and the city of Cyme in neighboring Aeolis. To the north, the Persians subdued rebel cities in the Hellespont. Aristagoras, seeing the Persians winning on all fronts, tried to save himself. He considered escaping to Sardinia but chose instead to go to Myrcinus, in Thrace, where Histiaeus had resumed building the town. Once there, Aristagoras and his reduced force continued making trouble, attempting to establish a colony of their own on the Strymon River. Aristagoras managed to secure a foothold in Thrace, but later died in battle while besieging a neighboring town.

Histiaeus, too, came to grief after his release from Susa. Artaphernes, whom he had met with in Sardis after his return from Susa, blamed him—correctly—for having incited the Ionian revolt. “You stitched up the shoe,” he told Histiaeus, “and Aristagoras put it on.” In 494 bce the people of Miletus refused to take him back as their ruler, and his attempt to capture the city by force failed.

Elsewhere, Persian diplomats worked hard to detach rebel cities from the alliance. They sent former Ionian tyrants to win back their peoples, but all of them were rebuffed. Meanwhile, Persia fitted out a massive fleet of 600 triremes. When ready, it set sail for Miletus, accompanied on the land route by a giant army.

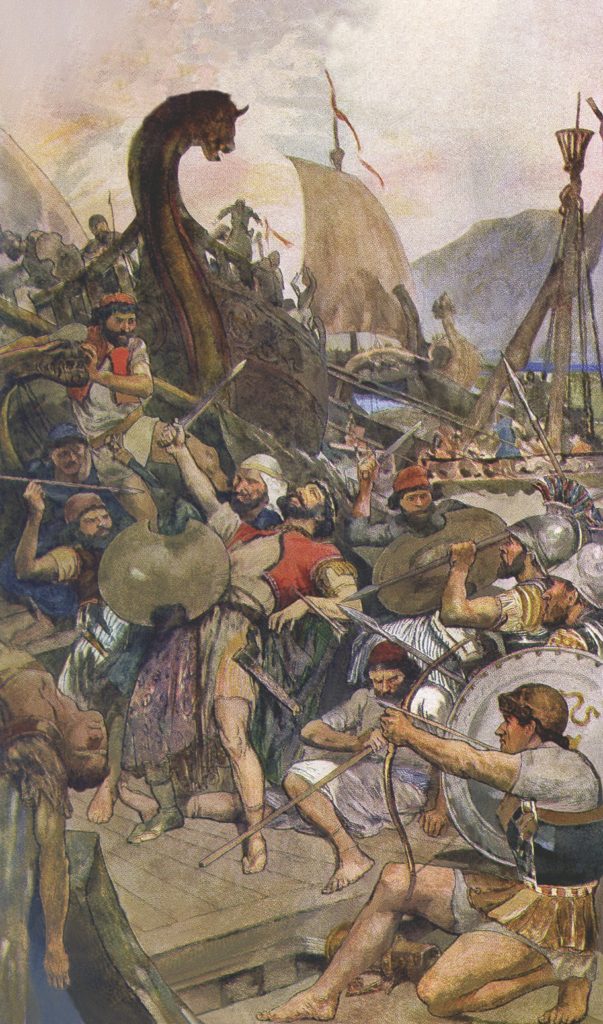

The Ionians prepared their own fleet of 353 triremes to meet the Persian force at the island of Lade, where they sometimes practiced naval maneuvers under Dionysius, a Phocaean admiral. Dionysius, who commanded one of the finest fleets in the Greek world, aimed to improve the battle tactics of the other Ionian naval contingents. His daily practice sessions involved training with armed troops on board as the Greek war galleys sailed in formation.

Dionysius showed the rowers how to perform the diekplous (breakthrough) maneuver, in which they would row into line, penetrate the enemy line, and then wheel around to ram the vulnerable sides and sterns of the opponent’s vessels. This advanced maneuver offered the Ionians their only real hope of defeating the Persian fleet, which was composed mainly of ships from Phoenicia. But the Phoenicians, the best sailors of the day, were already well versed in the maneuver, and Dionysus was in a race against time to instruct his own sailors in the tactic.

The precision and discipline needed to carry out the diekplous proved too much for some of the Ionian crews. As their resentment of the well-intentioned Dionysius boiled over, they went on strike, causing the whole effort to implode. The Samians, who were a major part of the Ionian Greek naval coalition at Lade, were so frustrated and worried by this collapse that they sought out their former tyrant, Aiakes, and struck a separate deal with him. When the naval battle at Lade began, the Samians simply turned and rowed away. This in turn sparked a disintegration of the Ionian battle line, and the Persians went after the remaining Ionians with a vengeance.

As the ships closed, they exchanged missiles: first arrows, then slingstones, then javelins. The Phoenician triremes, executing the diekplous and homing in on their targets with the guidance of their skilled helmsmen, rammed the Ionian ships, crushing their timbers and flooding them. Triremes, built with a positive buoyancy, usually did not sink outright. Instead, they settled low in the water, swamped, and became stuck. Meanwhile, warriors in enemy triremes came up alongside and prepared to board and seize the foundering vessels, waging hand-to-hand fights with swords, spears, and shields.

The 100 triremes of the naval contingent from Chios, the largest in the allied fleet, fought particularly well. Even after the Samians betrayed them, the Chians stayed put and managed to pierce the Persian battle line several times. Each Chian trireme had 40 hoplites aboard as marines, and they took on Persian galleys until almost all their own ships were lost. A handful of Chian triremes escaped.

Another survivor was Dionysius of Phocaea. During the fighting he had seized three Persian triremes, but he fled when the battle turned irretrievably against the Ionians. Knowing that it was just a matter of time before the Persians overran Phocaea, he made his way to Sicily. There he became a pirate, capturing Etruscan and Carthaginian ships in western Mediterranean waters but never harming Greek vessels.

The aftermath of the Battle of Lade was grim. Corpses floated facedown in the bloody water, along with the unfortunates who had tumbled overboard, beside broken timbers and cracked oars. Though the Ionians had put up a stiff fight, the Persian fleet triumphed and Greek naval power in Ionia was obliterated.

The way to Miletus was now wide open. The Persians, with their extensive siegecraft skills, easily overcame its high walls, just as they had done at Soli and Palaepaphos. The Persians not only constructed earthen siege ramps leading up to the walls but also tunneled under them, bringing battering rams forward to finish the job. Like the Palaepaphians, the Milesians defended themselves ferociously, but the result was the same. The Persians overran the defenses and seized the city, looting and torching the nearby temple at Didyma in delayed revenge for the destruction of the temple of Cybele at Sardis. They killed the majority of the Milesian men and enslaved the women and children. Next the Persians returned to Caria, where they had taken a rare beating at Pedasus, finally overrunning the province.

Histiaeus, playing the part of a freebooting pirate at Byzantium, captured merchantmen as they tried to transit the straits from the Black Sea to the Aegean. Leading troops drawn from Lesbos, he landed on Chios and then crossed the sea to attack Thasos. When news came that a Persian fleet was moving up from Miletus against the rest of Ionia, Histiaeus went to Asia Minor to find food. There, the Persian general Harpagus defeated him in battle and took him prisoner.

Recalling his previous service to the Persian crown, Histiaeus confidently believed that Darius would forgive his most recent transgressions. Artaphernes and Harpagus, fearing just such a possibility, had Histiaeus impaled on a spike and beheaded. Their fears that the Greek would win royal forgiveness were well founded. When they sent Histiaeus’s head to Susa (probably to prove that he had been executed), Darius was furious. He still appreciated Histiaeus and the other Ionian tyrants for helping him get his army back across the Danube after his miscarried Scythian invasion. Darius ordered his old comrade’s head buried with honors.

Having quelled the Ionian Revolt, the Persians continued mopping-up operations into 493 bce, with Chios, Lesbos, and Tenedos falling, along with the Chersonese in Thrace. The rebellion may have been over, but Darius had not forgotten his vow of vengeance. His colossal army would soon visit his wrath on all who had taken part in the destruction of Sardis, and that, above all, meant Athens. In 492 bce Darius appointed his son-in-law, Mardonius, as the supreme commander of a punitive invasion of Greece. Mardonius was politically astute, and he shrewdly placated the Ionians by removing the recently restored—and still very unpopular—tyrants from control of their cities. The democracies he set up instead were nonetheless securely under his control. It was an ironic end to a revolt that had begun with dreams of just such democracies.

It would take a long time for the gargantuan Persian army and fleet to reach Greece, but they were on their way. The Athenians had made a mortal enemy of Darius, the most powerful man in the Western world, and the failed Ionian revolt would lead to the Greco-Persian Wars. In 490 bce came the Battle of Marathon, where the Athenian hoplites finally defeated the Persians in open combat. Darius died of illness in 486 bce at age 64. In 480 bce his successor, Xerxes, avenged Marathon at the Battle of Thermopylae after overcoming the heralded last stand by 300 Spartans. The improbable Greek naval victory that same year at Salamis concluded the war in the Greeks’ favor.

The consequences of the Persian invasions would be felt long afterward. Athens would forge an empire of its own when it took the lead in chasing the Persians from the Aegean basin in the early sixth century bce. In the fourth century bce, Alexander the Great would use the devastation inflicted by the Persians as justification for his own war of vengeance against them. His conquest of the eastern Mediterranean altered forever the political landscape of the region and saw the establishment of brilliant Hellenistic kingdoms that dominated Persia’s former territories in Asia Minor, Egypt, Syria, and elsewhere for centuries to come.

The Greek acculturation of these areas in turn smoothed the way for a rising Rome to subsequently exert control over them. In modern times, the Greek battles for freedom from Persian control still loom large in Western memory. All these developments trace their origins to that fateful and fiery day at Sardis in 498 bce. MHQ

Marc DeSantis is the author of Rome Seizes the Trident: The Defeat of Carthaginian Seapower and the Forging of the Roman Empire (Pen and Sword Military, 2016).