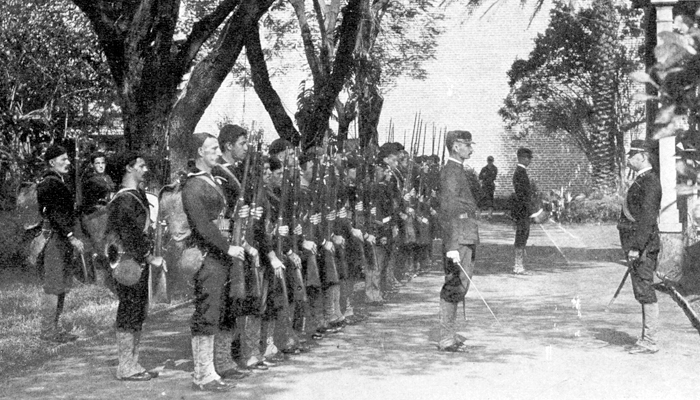

In the late afternoon of Jan. 16, 1893, 162 U.S. Marines and sailors disembarked from the armored cruiser Boston, at anchor in Honolulu Bay. Landing at the city wharf, they formed up and marched past Iolani Palace, saluting Hawaii’s reigning monarch as she watched from her second-floor veranda. Towing Gatling guns and field cannons, the troops set up in three positions. One Marine stood guard at the U.S. Consulate, while 40 others secured the minister’s residence. The main contingent of bluejackets, meanwhile, made a show of force and then retired to Arion Hall, then under lease as a Mormon house of worship, adjacent to Aliolani Hale (Government House) and across the street from the palace. After clearing out the pews and unfurling their bedrolls, they waited through a tense night. Hundreds of armed Hawaiians loyal to the queen stood by with orders not to provoke the Americans.

Boston’s troops had occupied Honolulu at the request of U.S. Minister John L. Stevens, who claimed the queen’s recent attempt to ratify a new constitution had put American property and lives in danger. In truth, he was facilitating a coup d’état, acting as mouthpiece for the Committee of Safety, a cabal of 13 men who had undermined the monarchy six years earlier and were worried this resurgent queen would harm their business interests—particularly sugar plantations.

The next morning these men presented a letter to Queen Liliuokalani, demanding she abdicate. The queen shrewdly drafted her own letter, ceding her authority not to the coup plotters but to the country whose warship and troops threatened her capital. She expressed confidence that once the facts were known, that government would “undo the action of its representatives and reinstate me.” After all, this kind of thing had happened before.

The fall of Hawaii’s last queen and the islands’ subsequent annexation by the United States is best understood as the intersection of two stories: The first explains their strategic value to a U.S. government eager to join the world’s great powers. The second describes the religious, economic and cultural Americanization of the Hawaiian people, which began the moment they encountered Western explorers.

The islands first dazzled European eyes when British Captain James Cook spotted their lush tropical slopes on Jan. 18, 1778, naming them the Sandwich Islands after First Lord of the Admiralty John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich. Careful to keep other European powers in the dark about his actual mission—to search for the fabled Northwest Passage—Cook had sailed his two ships, HMS Resolution and HMS Discovery, to Tahiti before heading north across the equator. After crossing roughly 2,700 miles of the Pacific, Cook and his crews encountered a sprawling, isolated archipelago that both dazzled and terrified them. Jungles teemed with exotic birds and foliage, and ancient stone irrigation ditches funneled water to crops. The Polynesian culture centered on kapu—its version of taboo. Hawaiians practiced human sacrifice to mark the death of a leader or appease Pele, the volcano goddess. Men never swallowed their saliva, instead spitting constantly, and they never ate with women—yet women held important leadership positions. A strict caste system separated the alii, the ruling class, from commoners and governed their interactions. A commoner, for example could be ritually clubbed or strangled to death for letting his shadow fall on the person or house of an alii.

Genealogy mattered more than anything. Hoping to have children by the mighty visitors, women aggressively solicited Cook’s sailors, returning to their villages with lice and venereal disease. As he sailed about the islands, observing thousands of canoes paddling out to greet his ships, Cook estimated the total Hawaiian population at 300,000. He continued northeast to map the West Coast of North America. On Cook’s return in February 1779 during an ill-starred season the superstitious islanders clubbed him to death, baked the flesh from his body and preserved his bones for the spiritual mana the Hawaiians believed they contained.

A prominent warrior named Kamehameha had visited Cook’s flagship, HMS Resolution, and fully grasped the value of the British weapons. In the years that followed he traded goods for guns and ultimately convinced two British sailors to teach his men their use, rewarding the pair with high office, wives and land. (Thus began the practice among Hawaiian leaders to appoint Western men to their inner circle.) Using every tool at his disposal—ranks of muskets, artillery mounted on double-hulled canoes, religious edicts and diplomacy—Kamehameha the Great ruthlessly subdued the islands one after another, uniting Hawaii for the first time in 1810.

For six decades the Kamehamehan dynasty adapted to the changes that came with each wave of new arrivals. On the heels of Kamehameha’s death in 1819 his widow Queen Consort Keopuolani broke kapu by permitting men and women to eat together—yet Pele did not erupt in protest. A year later Calvinist missionaries from New England filled the religious void, wisely linking evangelism with education. They invented a Hawaiian alphabet, printed Bibles, opened schools and by 1834 had raised the islands’ literacy rate from essentially zero to one of the highest in the world.

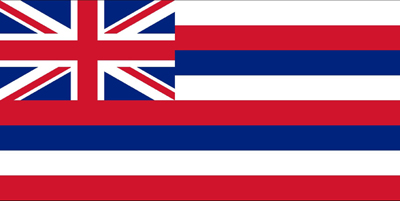

Western influence showed in the monarchy’s new flag. Laid out like the American flag, it featured the British Union Jack in the upper-left corner. Representing each of the main islands, eight horizontal stripes alternated white, red and blue. In 1839 Hawaii’s longest-reigning monarch, Kamehameha III, adopted a Declaration of Rights and the next year drafted a constitution establishing a parliament and judiciary. Meanwhile, the sleepy fishing villages of Lahaina and Honolulu grew into multicultural boomtowns, hosting hundreds of whaling and trading vessels, whose sailors clashed with the moralistic missionaries. Influenza, measles and other maladies also visited the islands. By the mid-1800s disease and warfare had reduced Hawaii’s population by two-thirds to about 80,000. By 1890 it had fallen to a low of 40,000.

To fill the economic gap when whaling and sandalwood sales plummeted, entrepreneurs brought in men from China, Portugal and Japan to work the sugar plantations. Although the Kamehamehas tried to diversify the economy with other exports like coffee and beef, sugar dominated the islands by the mid-1800s. Plantation owners such as German-American industrialist Claus Spreckels bought their own ships, railroads and refineries to streamline operations. They built company towns and diverted huge amounts of water, changing the islands’ ecosystems and topography. The sugar barons also loaned the crown money, then leveraged that indebtedness to secure legislative seats for their favored politicians.

Visits by foreign naval vessels periodically made Hawaii the site of intense saber rattling, such as in February 1843 when Britain’s Lord George Paulet used his command, the 26-gun frigate HMS Carysfort, to threaten Kamehameha III over a variety of business and diplomatic disputes. Paulet held the islands hostage for five months before the commander of the Pacific Station arrived, reprimanded Paulet and affirmed Kamehameha III as Hawaii’s rightful ruler.

In August 1849 a rogue French deputation took a turn, presenting a range of frivolous demands to Kamehameha III. When the king ignored them, French marines seized Honolulu Fort, spiked its cannons and ransacked the area. Negotiations for reparations on the $100,000 in damages dragged on indefinitely while French threats increased. As a British treaty with France kept London from intervening, Kamehameha III put Hawaii under the provisional protection of the United States, tacitly conceding to extend the Monroe Doctrine into the Pacific. American newspapers went wild with speculation Manifest Destiny could soon envelop the islands.

Kamehameha III put Hawaii under the provisional protection of the United States, tacitly conceding to extend the Monroe Doctrine into the Pacific

A change to Hawaii’s constitution provided for its first elected king, Lunalilo, to take the throne in 1873. The unmarried monarch died just a year later. Kamehameha IV’s widow, Queen Dowager Emma Kaleleonalani, was the people’s choice to succeed him, but her rival, David Kalakaua, defeated her through a legislative vote, avoiding a popular referendum. At the news a mob rushed the Honolulu Courthouse, killing one representative and wounding a dozen others.

In his first act as king-elect Kalakaua asked the commanders of the U.S. sloops of war Tuscarora and Portsmouth and British gunboat Tenedos to help quell the violence. Their collective bluecoats cleared the courthouse and square, then patrolled the streets for eight days. Thus Kalakaua’s 17-year reign began in debt to Western powers, an indebtedness that only grew. By accepting loans from the sugar barons to finance a lavish lifestyle and stumbling into scandal, he made it easy for political opponents to best him.

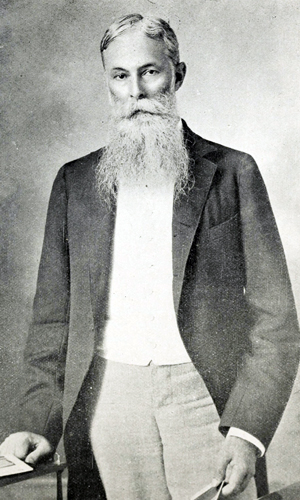

Lorrin A. Thurston, whose ancestors included some of Hawaii’s first missionaries, founded a secret society with other Westerners to press their advantage with Kalakaua. They formed a volunteer militia and on July 6, 1887, stationed 150 uniformed militiamen with fixed bayonets near the palace while coercing the king to sign what became known as the “Bayonet Constitution.” It kept Kalakaua on the throne but made him share power with the legislature and his ministers. He had no role in amending the constitution, and he couldn’t fire the cabinet. Thurston, the new interior minister, packed the cabinet with wealthy Americans and Europeans.

By this time the major powers were establishing footholds throughout the Pacific. In 1880 the French made Tahiti a colony. Germany took the Marshall Islands and Micronesia as a protectorate in 1885 and supported a faction struggling for control of Samoa against rival groups funded by the United States and Britain. Japan inquired about Hawaii, but the Americans kept courting the country economically. As early as 1872 naval intelligence had been mapping the Pearl River estuary, the largest and best protected port in the North Pacific, estimating how much dredging would be needed to prepare it for a fleet, while U.S. diplomats spent more than a decade tying a free trade deal for sugar to a lease on the harbor, which they finally secured in 1887.

The 1890 publication of U.S. Navy Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan’s The Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660–1783 blew the lid off a underway global shift in naval strategy and popularized a national security case for empire. In a nutshell, Mahan advocated moving from coastal defense and commerce protection to offensive sea control, replacing small squadrons with far-ranging battle fleets whose mission would be to concentrate firepower and prevail in a decisive battle, preferably far from the nation’s shores. Since navies of the era relied on steamships, it was vital to have coaling stations around the world to refuel them. This was music to expansionists’ ears, and they showered Mahan with international acclaim and honorary university degrees. Germany’s Kaiser Wilhelm II went so far as to have a translation of the book placed in every German naval library and compel his officers to read it.

Kalakaua died in early 1891, and his sister Liliuokalani assumed the throne. Seeking to lower the debts her brother left behind, Liliuokalani entertained proposals to start a lottery and tax the import of opium for the many Chinese workers in Hawaii. She also sought to abrogate the Bayonet Constitution, in part because she wanted to appoint her own cabinet ministers. With the help of Hawaiian legislators she wrote a new constitution and gave advisers a month to comment on it. Incensed at the proposed changes, Thurston’s faction courted American intervention.

The stage was set for six crucial days: Jan. 12–17, 1893.

On Thursday, January 12, Liliuokalani successfully lobbied the legislature to vote out the cabinet, allowing her to appoint ministers who shared her way of thinking. On Saturday, January 14, she declared the legislative session closed, then summoned her new cabinet to a meeting at the palace, expecting them to sign the new constitution. Coached by Thurston, they refused, claiming—quite correctly—she was asking them to disobey current law. She furiously argued with them but in the end was forced to admit she had overreached. With memories of the 1874 bloodshed firmly in mind, she backed down, not wanting to give the foreign warships in the harbor any excuse to intervene this time. That afternoon Thurston’s allies set up the 13-member Committee of Safety. They spent Sunday on horseback rounding up support.

Liliuokalani called a meeting for noon on Monday, January 16, urging supporters at the palace square to remain calm. Just a few blocks away Thurston’s Committee of Safety was holding its own meeting, denouncing the queen. They had written a letter to Minister Stevens, pleading for help: “We are unable to protect ourselves without aid and, therefore, pray for the protection of the United States forces.” Captain Gilbert C. Wiltse, commanding the 3,240-ton armored cruiser Boston, said Stevens could count on his troops, and at about 5:30 p.m. they occupied the city. Estimates vary, but Liliuokalani had at least double the number of armed men at her disposal to counter the Americans. Given Hawaii’s history with armed occupation, however, she thought it prudent to wait out this latest disturbance. Thurston worked through the night writing a justification for her overthrow, while other members of the Committee of Safety asked Sanford B. Dole, a justice on Hawaii’s Supreme Court, to act as president.

On Tuesday, January 17, Dole accepted the presidency, and the Committee of Safety requested Liliuokalani’s abdication. She stalled, asking for time to meet with her secretary and compose the appropriate document. In it she wrote, “I yield to the superior force of the United States of America, whose minister plenipotentiary, his excellency John L. Stevens, has caused United States troops to be landed at Honolulu and declared that he would support the said Provisional Government.” Dole endorsed the letter, perhaps not realizing he was agreeing to let the U.S. government decide Hawaii’s fate. President Benjamin Harrison favored the expansion of American interests in the region. But his successor Grover Cleveland, who took office on March 4, grew leery and called for an investigation into the overthrow.

President Cleveland immediately sent former U.S. Representative James H. Blount of Georgia to Hawaii as a special commissioner, with orders granting him “paramount” authority over the American civil authorities and troops. Arriving in Honolulu on March 29, the tactful Blount first directed provisional President Dole to lower the American flag over the Government House and ordered the bluecoats to return to Boston. The commissioner stayed for five months, gathering testimony and documents from all sides. Among the documents was an incriminating letter from Minister Stevens to former U.S. Secretary of State John W. Foster, in which Stevens wrote, “The Hawaiian pear is now fully ripe, and this is the golden hour for the United States to pluck it.” In his final report Blount concluded Stevens had called on Boston’s troops not to protect U.S. property, but rather to back the coup. Cleveland promptly dismissed Stevens.

President Cleveland’s administration offered Liliuokalani a deal: grant amnesty to those who had deposed her, and the United States would restore the monarchy. From the queen’s perspective that was impossible

In mid-November 1893 President Cleveland’s administration offered Liliuokalani a deal: grant amnesty to those who had deposed her, and the United States would restore the monarchy. From the queen’s perspective that was impossible. Thurston and the others had committed treason and needed to be punished, or they might try again. She reportedly told Stevens’ replacement, U.S. Minister Albert S. Willis, the coup leaders deserved to be “beheaded.” Whether or not she meant that literally, the idea of the dark-skinned queen bringing back sacrificial practice made the American press howl. On December 18 Liliuokalani finally sent a letter saying she would accept Cleveland’s deal—but it was too late. That same day Cleveland sent her notice he was turning over the matter to Congress. In February 1894 the Senate released its own report, which absolved of all blame everyone involved in the overthrow—Liliuokalani not included. In May the Senate went even further, issuing a resolution opposing the queen’s restoration. The provisional government slammed the door on July 4 by establishing the Republic of Hawaii, with Dole as president.

On Jan. 6, 1895, Honolulu police disrupted a plot to overthrow the republic and routed the royalists after three days of skirmishing. After finding weapons and incriminating documents in a search of Liliuokalani’s residence, authorities arrested the deposed queen. Convicted with 192 others by a military tribunal, she abdicated, hoping to save her compatriots’ lives. To avoid creating martyrs, Dole ultimately commuted the sentences of all those convicted and kept Liliuokalani under house arrest for nearly two years before pardoning her. On her release Liliuokalani mortgaged her property and used the money to travel stateside in a last-ditch effort to reclaim her crown. She published her memoirs, detailing the coup from her point of view, and presented the U.S. Senate with the results of a petition against Hawaii’s proposed annexation. Her backers had shuttled between the islands capturing signatures from half of Hawaii’s native population. Their effort helped defeat ratification of an 1897 annexation treaty.

Hawaiian royalists celebrated their victory, but they failed to realize the 1896 U.S. presidential election had shifted the political winds. With the election of William McKinley as president, Sen. Henry Cabot Lodge and other expansionists—including Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt—finally had a commander in chief who would allow them to implement Mahan’s naval strategy in a deliberate bid for empire.

The final blow to Liliuokalani’s efforts came with the Feb. 15, 1898, sinking of the USS Maine in Havana Harbor, which made war with Spain inevitable and a coaling station in Hawaii essential. This time annexation threaded the loophole of joint resolution, requiring a simple majority in both houses. The Senate approved the bill on July 4, and McKinley signed it law three days later.

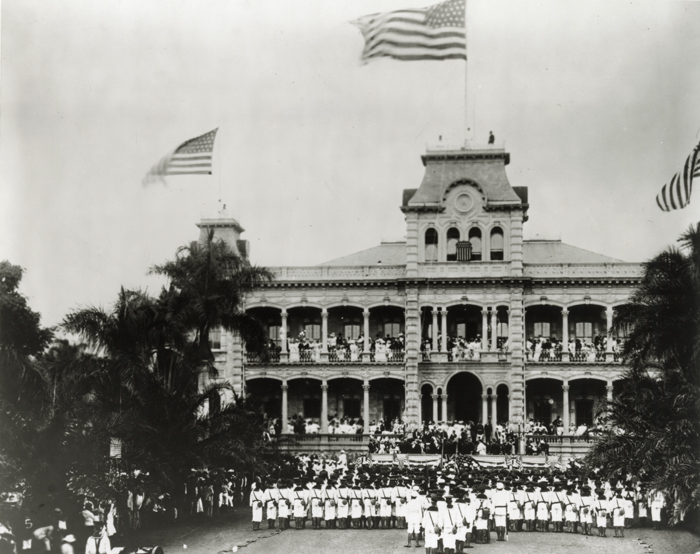

The annexation ceremony outside Iolani Palace marked the last step in Hawaii’s Americanization. On August 12 native Hawaiians in Western suits and dresses offered up Christian prayers, read speeches in English and stood alongside American troops from the protected cruiser USS Philadelphia while their flag was lowered. The former Royal Hawaiian band and the ship’s band from Philadelphia together played the Hawaiian anthem, “Hawaii Ponoi,” then struck up “The Star-Spangled Banner” as Old Glory rose up the staff and snapped in the breeze. The sight proved too much for the Hawaiian players, who abandoned their instruments and left the ceremony in tears. MH

Paul X. Rutz, a 2001 graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy, is a painter and freelance writer whose articles have been published in the Huffington Post, Army History and other publications. For further reading he recommends Captive Paradise: A History of Hawaii, by James L. Haley, and Hawaii’s Story by Hawaii’s Queen, by Liliuokalani.