Even in Puritan Boston, a wealthy man got away with victimizing a young woman

In August financier Jeffrey Epstein committed suicide in the jail cell in which he was awaiting trial on federal charges of sex trafficking and conspiracy to traffic minors for sex. FBI agents who raided Epstein’s Gotham mansion had found thousands of lewd images of young women and underage girls; the court of public opinion viewed his end as no loss.

But even this self-enforced verdict had been a long time coming. In 2008, after a lengthy investigation occasioned by allegations from 36 girls that Epstein had molested them at his Palm Beach mansion, he and federal prosecutors for the Southern District of Florida agreed to a deal whereby Epstein pleaded guilty to a state charge of soliciting prostitution from a minor and had to register as a sex offender. The court sentenced Epstein to 18 months in jail. He was released after 13.

Perhaps the most telling comment is Christ’s: “Whoso shall offend one of these little ones…it were better for him that a millstone were hanged about his neck, and that he were drowned in the depth of the sea.”—an adjuration Epstein seems to have taken to heart. But his case raises questions about the law itself. The Miami Herald, which has tracked the Epstein case like a bloodhound, called his 2008 plea bargain “the deal of a lifetime.” Was that arrangement made because of Epstein’s many connections with the rich and powerful? Those connections comprise a long bipartisan list. Former president Bill Clinton told New York magazine in 2002 that Epstein was “a committed philanthropist” whose “insights and generosity” Clinton “especially appreciated.” (After Epstein’s recent arrest, Clinton denied through a spokesman knowing anything about the financier’s “terrible crimes.”)

In the same New York article, Donald Trump called Epstein a “terrific guy” and “a lot of fun to be with.” Trump added, “It is even said that he likes beautiful women as much as I do, and many of them are on the younger side.” (President Trump told reporters in July “I had a falling out with him….I was not a fan of his, that I can tell you.”) The federal prosecutor who struck the 2008 deal, Alexander Acosta, became Trump’s labor secretary in 2017. After news of the new case broke, Acosta defended the deal he had made, claiming that state prosecutors in Palm Beach had planned to go even easier on Epstein, bringing a charge of soliciting that would have required only that he pay a fine. Acosta resigned his cabinet post July 12.

Investigators and attorneys, journalists and partisans, have wrestled with this matter for months—as they should. For centuries, America’s wealthy and powerful have gotten away with grotesque sex crimes.

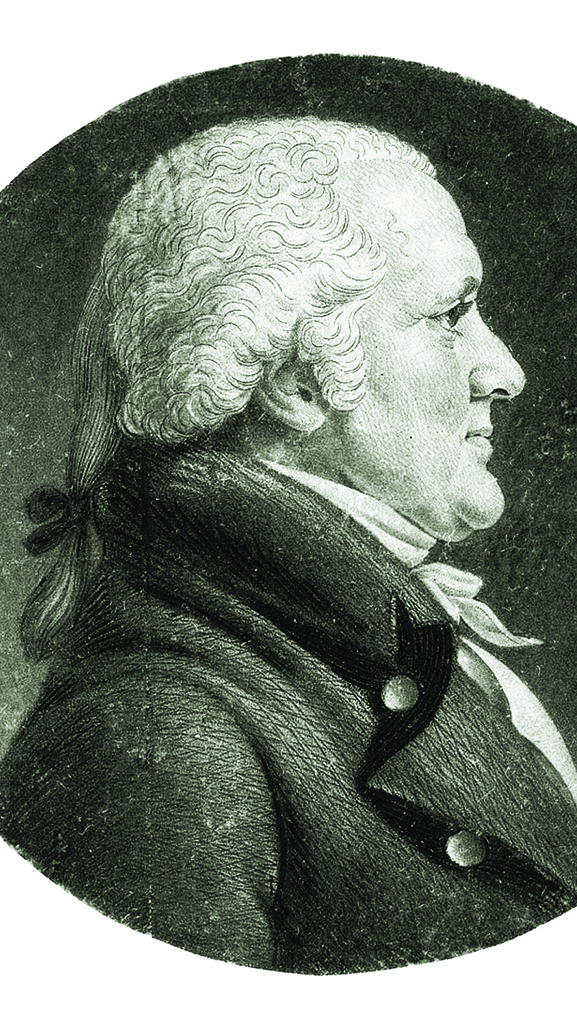

Perez Morton was born in 1751, son of a Boston tavernkeeper. Educated at Boston Latin School and Harvard, he climbed into the local elite, in the early 1770s becoming a lawyer, a Mason, and a revolutionary. His friends included future Massachusetts governor Thomas Bowdoin and future American president John Adams. A year after the Battle of Bunker Hill, Morton was chosen to speak at the re-burial of the remains of that fight’s most famous casualty, Dr. Joseph Warren. Morton’s oration, a specimen of the high style of the day, dwelt on the decedent’s virtues. The greatness of Warren’s soul, said Morton, “shone even in the moment of death, for…in his last agonies he met the insults of his barbarous foe with his wonted magnanimity.” This was not Morton’s most famous literary contribution: earlier he had supplied the lyrics for William Billings’s four-part round, “When Jesus Wept,” still sung today.

When Jesus wept, the falling tear

In mercy flowed beyond all bound;

When Jesus groaned, a trembling fear

Seized all the guilty world around.

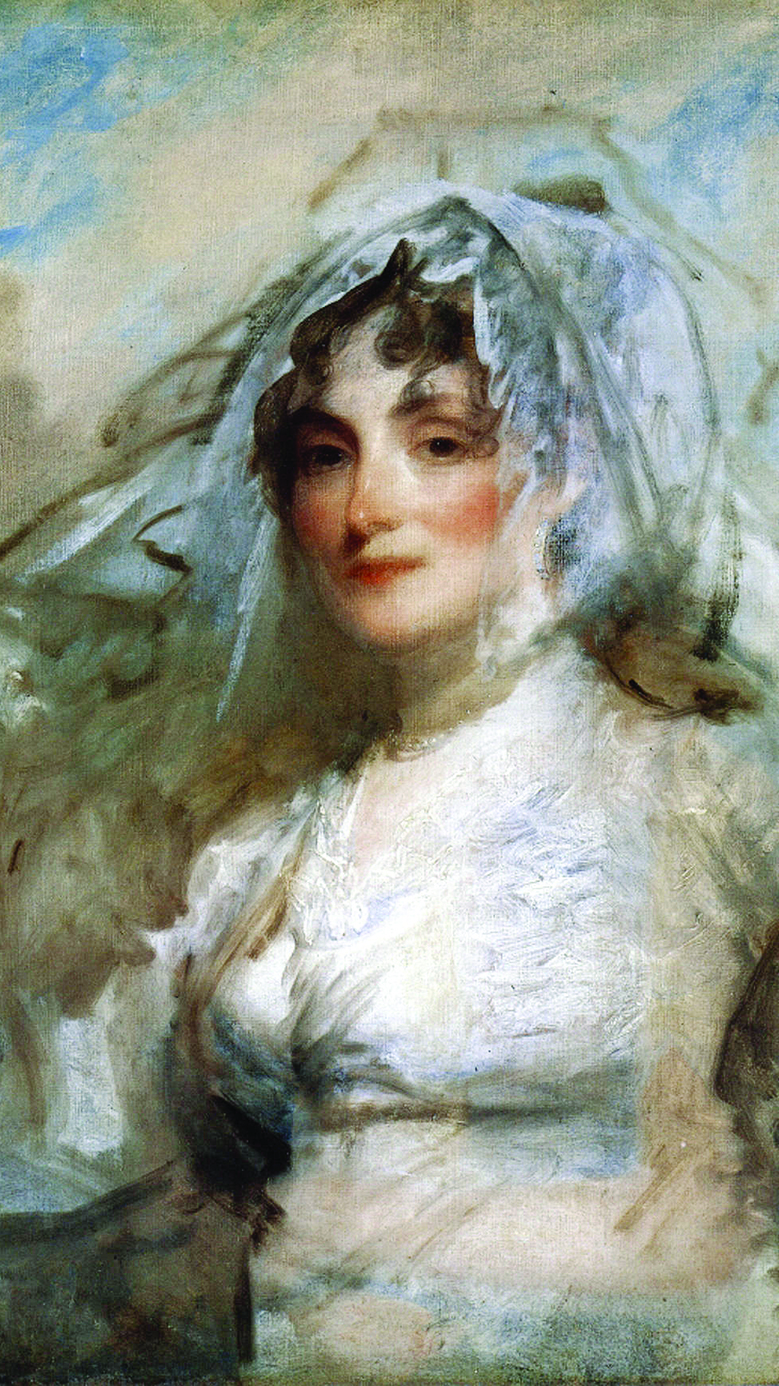

In 1781 Morton took another step up in the world, marrying Sarah Wentworth Apthorp, handsome daughter of a wealthy merchant and slave trader. Gilbert Stuart would paint Sarah’s portrait three times, as if never tiring of her. The Mortons moved into the Apthorp family mansion on State Street, a premier Boston address, and had five children.

Sarah’s younger sister Frances, or Fanny, came to live with the couple in the mid-1780s. Dates involving Fanny are hazy. She and brother-in-law Perez had an affair, and she became pregnant, a less hazy circumstance.

Betsy Cranch, a niece of Abigail Adams who lived nearby, wrote in her diary that Fanny was “very unwell” (period code for with child). Fanny bore a daughter in 1787 or 1788.

Fanny Apthorp was not underage, by our standards or by those of her time, but she was young: 20 or 21 when she conceived. The father was 15 years older and socially prominent. The power differential was stark.

So was the disparity in the principals’ fates.

Sarah Apthorp, the aggrieved wife, could have filed for divorce, available in Massachusetts since colonial times, even for women. Instead Sarah remained with Perez—he died in 1837, she in 1841—albeit on apparently cooler terms; they produced no more children.

Sarah, a poet all her life, began publishing; one of her most famous works, “The African Chief,” a lament for a slave, contains the lines

The hard race of pallid hue

Unpractic’d in the power to feel

that could also apply to Perez. Sarah got a measure of revenge in an affair of her own, with founding rake Gouverneur Morris. She, her lover, and her husband even dined together once in summer 1803. “Monsieur was cordial, all things considered,” noted Morris in his diary.

Perez Morton could afford to be cordial. His familial adultery left him virtually unscathed. Charles Apthorp, Sarah’s and Fanny’s brother, defended the family honor by challenging Perez to a duel, but the shoot-out seems to have been scheduled for form’s sake; the sheriff was present at the chosen spot when the would-be duelists arrived, in order to thwart the face-off. An Apthorp neighbor anonymously published a novel, The Power of Sympathy, that draped the scandal with the lightest of disguises: the fictional seducer’s surname is “Martin.” Perez bought up most of the press run; a dozen copies were found decades later in a trunk. His long political career, extending into the 19th century, included service as speaker of the Massachusetts House and state attorney general—chief upholder of the laws.

Fanny Apthorp was long gone, dead from a self-administered laudanum overdose in 1788; at most, her daughter would have been 20 months old. In a note she addressed to Perez in which she wrote of her “guilty innocence.” Of the child, nothing is known.

The well-connected man flourished; women suffered, in silence or in suicide.

Perez Morton was not alone. Gouverneur Morris’s affairs mainly involved unhappily married women, but while living abroad he carried on with a landlady’s two daughters, one evidently young—she “begins to feel the gentle hint from nature’s tongue,” he wrote creepily in his diary. Thomas Jefferson is now generally known to have fathered children by his slave Sally Hemings; historian Annette Gordon-Reed depicts the relationship as long and intimate. But there cannot be real consent between owned and owner.

When morality sleeps, age will prey on youth, power on impotence, wealth on the dispossessed. What may have changed, for the better, is the legal and journalistic means, and occasionally the will, to bring the guilty to justice, however delayed.

This story appeared in the December 2019 issue of American History.