Blake Bailey demonstrates that it’s not always prudent to get the last word, even from the grave

It’s hard to think of a major novelist whose literary output has been more explicitly autobiographical than Philip Roth’s. Whether it’s Jewish city kid Neil Klugman trying to fit in with Brenda Patimkin’s assimilated suburban family in Goodbye, Columbus or frequent protagonist Nathan Zuckerman, the Newark-born writer who appears in nine of Roth’s novels, the idea of Philip Roth the man figures prominently in most of his books. Moreover, Roth wrote a pair of titillating memoirs and made “Philip Roth” the main character in three novels. Having something interesting to say about the flesh and blood Philip Roth that the author hadn’t already said himself is quite the task. Especially so soon after Roth’s death in May 18.

By Blake Bailey

W.W. Norton 2021, $40

Blake Bailey, author of esteemed biographies of Richard Yates, John Cheever, and other literary titans, tells Roth’s story in a consistently entertaining fashion. From the “spoiled” second son of hard-working, first generation Jewish immigrants to “boy wonder” author to literary rapscallion to hyper-productive elder statesman of American letters, Bailey fills in the blanks, serving nearly as a defense counsel for Roth in his multiple public and private feuds. A prose stylist of the highest order, he renders the blow-by-blow of Roth’s life in vivid detail.

Nevertheless, Bailey tends to calcify impressions that Roth’s readers had of the man from his own prose. Philip Roth: The Biography is, in fact, an authorized biography. Roth agreed to work with Bailey in 2012 and participated fully in the project, providing Bailey with his papers, pictures, and countless hours of recollections. The results are a comprehensive portrait. For better or worse, The Biography certainly reads like something authorized—or maybe an apologia, often couched in terms that do not flatter Roth. Philip Roth demonstrates that it is not always prudent to get the last word, even by proxy.

Roth’s preoccupation with his legacy threads throughout, thoroughly abetted by Bailey. The author of Portnoy’s Complaint responds to accusations of being a Jewish anti-Semite. He ripostes all the literary critics he denounces for flagrantly misinterpreting his work for five decades. The book opens with a display of Roth’s animus toward the Nobel Prize Committee, which repeatedly snubbed him. Most unflatteringly, the book serves as an echo chamber in which Roth claps back at many of the numerous women with whom he had romantic relationships. Roth was, evidently, not one to forgive and forget—with Bailey’s aid, he pillories several paramours and succeeds at coming off as incredibly bitter.

In many a biography, the making-of-the-man passages can get a bit tedious, but Bailey’s depiction of Roth’s ancestry and upbringing is thoroughly stimulating reading and by far the book’s strongest sections. Considering Roth’s and Irving Howe’s mutual enmity, it is interesting the degree to which the striving of the Roths and the Finkels, his mother’s family, amid the hustle and bustle of early 20th century North Jersey reads like Howe’s classic, The World of Our Fathers. Philip Roth’s strong opening chapters help compensate for later digressions into his midlife amours, which read more like an upmarket version of a Jacqueline Susann novel than The Life of Samuel Johnson. But perhaps a comprehensive Roth biography ought to read more like the sexualized popular culture he played no small role in creating than like a classic literary biography.

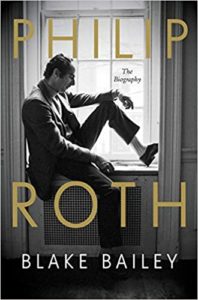

For all its faults, Philip Roth is essential reading for any fan. No matter which book of his you may be reading, the narrative offers a handy Baedeker’s for the places and events in the life that likely inspired the writing. In addition, Norton’s designers and binders have delivered an object d’art. The cover image of Roth at a windowsill telegraphs the brooding tone within, just as a black-and-gold dustjacket evokes the gravitas he earned in half a century of writing. Dozens of pictures of Roth’s family, friends, and lovers adorn the text, shorthand for the man-in-full portrait Bailey aspires to. —Clayton Trutor teaches History at Norwich University in Northfield, Vermont. His book Loserville: How Professional Sports Remade Atlanta and Atlanta Remade Professional Sports will be released in September by the University of Nebraska Press.

This story contains an affiliate link. If you buy through this page, we might get a commission. Thanks!