The 1935 Marine Corps Manual for Field Musics noted: “A march played to signal that the troops will be paid,” known simply as “Pay Call,” would be sounded to announce payday. In the days before check-to-bank, an officer at the company, squadron, battery level paid his enlisted men in cash. This created a direct link from the unit to the men for services rendered.

The pay officer designee, accompanied by an armed guard, was required to present himself at the disbursing office, verify the amount of cash received and sign for his unit’s payroll. He would then set up his own “disbursing office”—usually in the unit’s classroom, where he would lay out the money on a table and organize it by denomination: ones, fives, tens and twenties. The armed guard was conspicuously posted near the pay officer.

The unit’s senior enlisted man, typically a first sergeant or gunnery sergeant, would send runners through the area announcing, “Pay Call.” Then men lined up in single file in front of the table. Strict silence was observed.

The pay officer read the names of the men in alphabetical order. When a name was called, the man presented himself at the table. The officer stated the amount of pay and counted it by denomination. The man acknowledged his payment by saying, “Sir, the pay is correct,” and signed the payroll sheet. He might be asked if he would like to donate money to help the unit meet its annual goal for the Navy Relief program, which provides assistance to members of the Navy and Marine Corps. Other “donations”—pay advances, gambling debts, etc.—were made outside the room, away from scrutiny.

After the last man in the alphabet was paid, the pay officer dutifully closed up shop and delivered the payroll sheet and “leftover” cash to the disbursing officer. “Leftover” meant cash to pay those who were not physically present for pay call. The pay officer was responsible for shortages and required to make up the difference out of his own pocket.

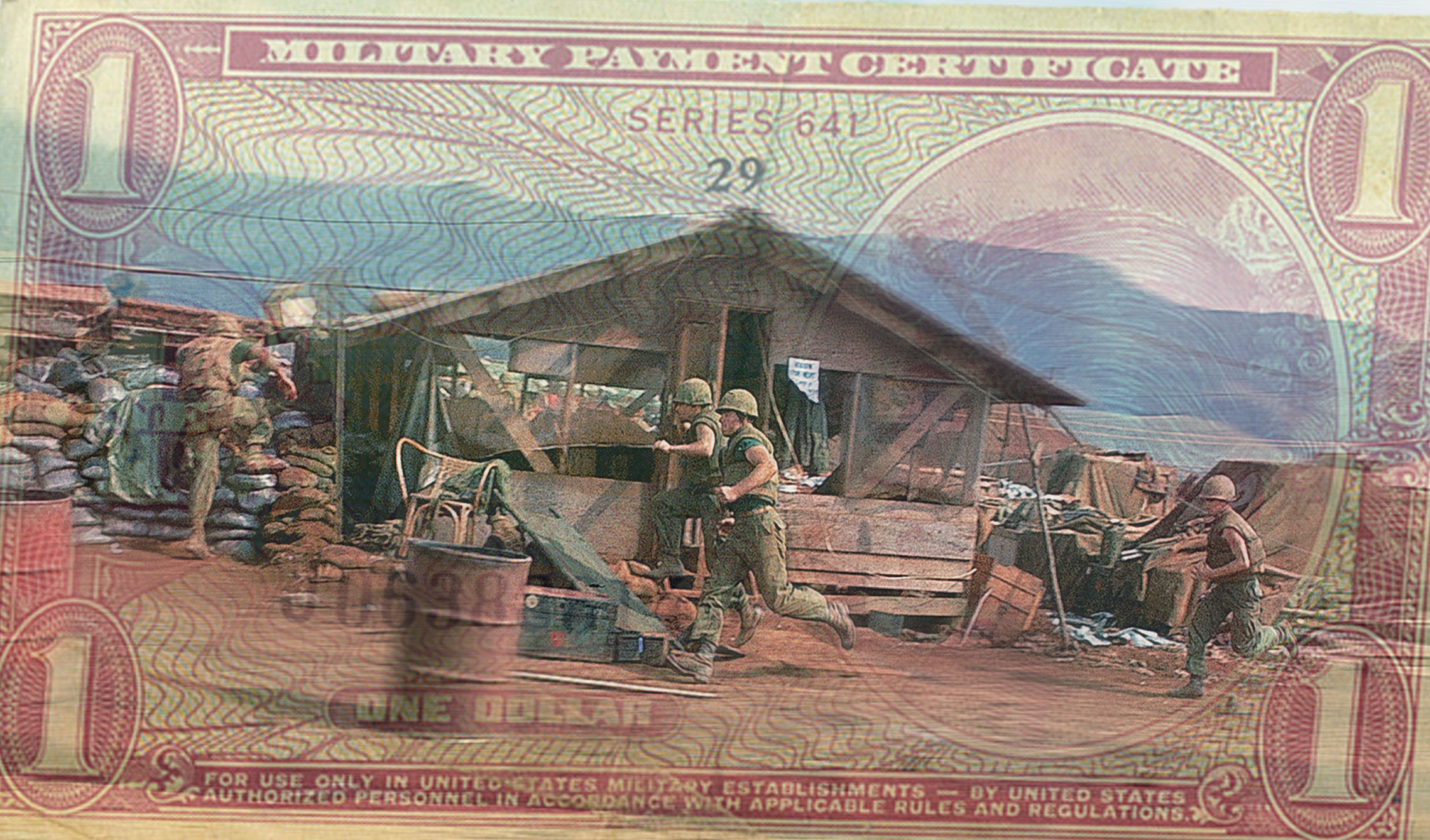

During the Vietnam War, pay was issued in “military payment certificates,” commonly shortened to MPC, instead of cash. These were issued by the Defense Department and denominated in amounts of 5 cents, 10 cents, 25 cents, $1, $5, $10 and $20. The military-issued certificates were given to deployed servicemen to stabilize the local economy by eliminating U.S. currency in circulation. To prevent MPCs from being used as a primary currency in South Vietnam, as well as to deter black markets and reduce hoarding, the banknote styles were frequently changed. Military payment certificates issued in Vietnam reached their zenith in 1968 and were discontinued in 1973.

The pay system in Vietnam was modified to allow American troops to draw only a certain amount on payday. For example, an individual might have $200 in his account but only draw $10 on payday. Most grunts drew only a small amount because there was simply no place to spend it in the field. Prior to payday, a roster was passed around, and each man initialed how much he would like to draw. He received that amount in MPC.

In the Marines, the high command was committed to paying troops the money owed—even under the harshest circumstances. A notable example was the determination in early 1968 to pay Marines engaged in fierce fighting at the Khe Sanh combat base in northwestern South Vietnam near the Laotian border. On Jan. 21, the North Vietnamese Army began shelling the base with artillery, rockets and mortar fire. Over the next 77 days, the 6,000 men of the garrison were subject to a daily bombardment. The base was surrounded by an estimated 20,000 North Vietnamese fighters.

I was at the base as commanding officer of Lima Company, 3rd Battalion, 26th Marine Regiment, 3rd Marine Division. We defended Khe Sanh’s Red Sector on the northwest side of the perimeter. The 3rd Battalion’s India and Mike companies defended Hill 881S, about 4 miles west of the base. When the NVA fired artillery, the rounds passed over the hill, breaking the sound barrier and making a distinct “POP.” At that point, the hill’s defenders radioed the base to send an alert about the enemy artillery: “Arty, arty, Co Roc Mountain, 220 degrees.”

Horns and sirens would go off, giving the garrison a few seconds warning before the dreaded “ZZZZZ” sound announced the earthward plunge of an incoming round. The garrison’s reaction has been described as resembling prairie dogs disappearing into holes at the first sign of danger.

Despite the imminent threat of death and destruction, a call to higher duty loomed over the Khe Sanh garrison—PAYDAY!

As incoming fire blasted Khe Sanh during the first week of the siege, I was preparing to defend the perimeter and evacuate casualties when I was notified that I needed to designate a pay officer. I was quite taken aback. “Pay officer?” I thought. “What the hell! What in the world do we need money for?”

Later I found out the garrison actually did need cash. On behalf of a grateful nation, each man received one can of Coca-Cola…for which he had to pay 10 cents! We laughed about having to pay for our Cokes when the government was dropping millions of dollars worth of ordnance all around us on North Vietnamese positions.

I decided not to fight “city hall” and designated a pay officer, the company’s junior officer, 3rd Platoon 2nd Lt. Dan Madison. Dan returned with a bag full of MPC and set up shop in front of his below-ground bunker. He laid the bills in neat piles on a 2-by-4 his platoon sergeant had scrounged.

As Dan set up, the base came under intermittent shelling. The company perimeter happened to be on the gun-target line—the straight line between the firing enemy weapon and the projectile’s point of impact. This meant that short rounds hit Lima Company and not positions farther down toward the runway and logistics support area. It was obvious we couldn’t assemble the entire company for pay call, so we decided to call up one fire team at a time, starting at one end of the perimeter and working our way around during lulls in the shelling.

The first fire team to be called spread out cautiously and made its way to Dan’s bunker, in what we called the “Khe Sanh Two-Step”— nestling a helmet under an arm to better hear incoming rounds while walking close to various dips and holes in the ground to take quick cover during the intermittent shelling.

As each payee’s name was called, that man scampered up to the makeshift “pay table,” where Dan counted out the cash, verified the amount, got the Marine’s signature and sent him on his way. Periodically flurries of incoming enemy fire forced everyone to make the “prairie dog” maneuver and temporarily forget the cash lying on the 2-by-4. A few times, someone brushed the table and scattered bills on the ground in haste to take cover.

When the last few men reported to be paid, Dan found he was short a couple of hundred dollars—a heck of a lot of money in those days. Dan admitted a few close calls had rattled him, so his counting might have been less than accurate. Or it could have been that a few bills got blown away in the confusion. Or maybe a “light-fingered” Marine had seized the opportunity to grab some extra hazardous duty pay while everyone else scrambled for cover. In any event, no one knew what happened. Dan, however, remained definitely on the hook for the money.

As word got around, several members of Dan’s platoon started a collection to reimburse him for the loss. When I heard what happened, I determined that the money qualified as a “combat loss” and wrote a detailed narrative recommending the loss be written off the books. We gave all the donations back to the troops.

Two years afterward I was stationed at Quantico, Virginia, when I received a harried call from Dan saying the Marine Corps was trying to collect the lost money from him. I considered the Corps’ attempt to be pure B.S. and dutifully wrote yet another letter explaining the circumstance of the loss, with an emphasis on its uniqueness. I forwarded the letter through my boss, Maj. Gen. Raymond G. Davis, who added his endorsement. That was the last time Dan and I heard of the infamous “Pay Roll Caper.” V

Col. Dick Camp retired from the Marine Corps in 1988 after serving 26 years. He was in Vietnam 1967-68 as an infantry company commander and aide de camp to Maj. Gen. Raymond G. Davis. Camp, who lives in Fredericksburg, Virginia, has written 15 books and over 100 magazine articles.

This Reflection is featured in the October 2020 issue of Vietnam magazine. Do you have reflections on the war you would like to share? Email your idea or article to Vietnam@historynet.com, subject line: Reflections

For more stories from Vietnam magazine, subscribe here: