“You’re on tomorrow,” Captain John Poyen, 357th Squadron intelligence officer, tells me the day before the mission. It’s November 25, 1944, and I’m a 20-year-old first lieutenant P-51 pilot from Brooklyn, New York, assigned to the 357th Squadron, 355th Fighter Group, Eighth Air Force, and based at Station 122, in Steeple Morden, England.

That night I sleep in wool long johns over a T-shirt and boxers. The less I need to suit up tomorrow, the better. I also put on the first of three pairs of socks, since layers mean warmth. At high altitudes—bomber escort levels—cockpit temperatures can dip to minus 60 degrees.

I sleep soundly, unlike before my first mission. Then I was a replacement pilot who’d just been thrown into a group of strangers. Now, with 26 missions under my belt, I know I’m part of a high-spirited team, men who will fight to the death for each other.

Rise and Shine

At 7:15 a.m., Poyen is tapping my shoulder. I say, “Okay, John.” I can hear the B-17s warming up at the Bassingbourne airfield, five miles away. Phil McHugh, nearest the door, gets wakened first. Next Ken Miller. Willy Reiff groans and has to be shaken awake. Bob Crandall politely says, “Thanks, John.” Buzz Lamar lets out an expletive. Charley Kelley, in the bunk next to mine, says, “Yes sir!” as if on parade. Ted Ludeke rolls out of bed and starts dressing before Poyen even reaches him.

I put on my shirt, pants and belt, second pair of socks and heavy high lace-up shoes. Then I head for the latrine to brush my teeth and wash up. I don’t have to shave so my oxygen mask will fit snugly: I still don’t shave but once every two or three days.

I climb into my overall flight suit. On the left thigh there’s a 4-by-4-inch clear glassine patch beneath which a mini-map of Germany is inserted. On my right shin is a zippered cargo pocket to hold my escape kit, on my left shin a sheathed knife. Next I strap on my shoulder holster, with a loaded .45-caliber pistol. Finally I pull on my A-2 flight jacket and officer’s cap. I’m ready for breakfast.

Today there are 16 of us from the 357th riding to the officers’ mess. Two years ago few of us had ever been in a plane. Now we’re privileged to be flying state-of-the-art fighters. Most of us are in our early 20s. Although our backgrounds vary, we share the same motivations: patriotism, optimism and loyalty to each other.

At the mess hall I eat as much as I can—orange juice, oatmeal with thick cream, scrambled eggs and fried potatoes, plateful of SOS and hot cocoa—for two reasons: I won’t get hungry if it’s a long mission. And I won’t need food too soon if I’m shot down.

The Briefing

Inside the big Quonset briefing hut are a dozen or so long benches, quickly filled by about 50 pilots. A cloth shroud covers the back wall, and an intelligence officer faces us, holding a wooden pointer. At first there’s some conversation and smoking. Then a loud “Ten-HUT!” announces the entry of the mission commander, Major Emil Sluga, who’s built like a wrestler.

The intelligence officer pulls back the shroud, revealing a map of central Europe, and the room falls silent. There are two black cords dotted with pushpins, starting at Cambridge (10 miles north of us) and ending at today’s target in Germany. The cords show the bomber groups’ routes to the target. Attached along the cords, each group has a cardboard cutout resembling a bomber, with its group number. I count 12 bomb groups. Red cords show the routes of the nine escorting fighter groups. Where red and black cords meet are the rendezvous points of each fighter group with its assigned bomb group. Adding it all up, it looks to be a raid of about 1,000 bombers, with escort of about 450 fighters.

“Today we’re going to escort the bombers to…Misburg,” says Major Sluga, pointing to mid-Germany. The city is covered by overlapping circles of red, which show the target’s anti-aircraft strength. The more red, the heavier the enemy flak. As homeland Germany’s largest oil refinery complex, Misburg has sizable red areas.

Sluga points to the lead B-24 group and says: “We’ve got the first box of ’24s. We pick them up at 10:45…here at Ijmuiden,” pointing to the Dutch coast. “We cover them to the target and take ’em back to Dummer Lake. We hand ’em off there to the 339th Group. I’ll be leading the group in the 358th Squadron, Captain Fortier has the 354th, Captain Bille the 357th. Any questions? No? Good.”

Sluga doesn’t mention our role: to protect the bombers no matter what. That’s taken for granted. While he talks I draw our 355th Group’s route in crayon pencil on my flight suit’s glassine patch over the mini-map of Germany, along with the timing points and compass headings. So do the others.

“Captain Lewis will cover the German defenses.” Sluga hands over the pointer, and Daniel Lewis says: “Well, as you can see, the refinery target is pretty well protected by anti-aircraft. This Misburg refinery processes a third of all Germany’s oil. It’s very important that we put it out of commission. I mean, destroy it. Our last reconnaissance shows some new flak batteries on the north, here…and on the western side, over here…very heavy.” He pauses, then asks, “Any questions, men? OK, I’ll turn it over to Meteorology.”

No word about enemy fighters. But we all know what to do: attack on sight, per Maj. Gen. Jimmy Doolittle’s welcome directive when he took over the Eighth Air Force Fighter Command. Before that, fighters had been required to stay with the bombers they were escorting until they were attacked, which gave the Luftwaffe the initiative. Now we were more effective. Our number of victories had increased and, more important, fewer bombers were lost. Nobody is worried about enemy fighters, just the anti-aircraft batteries. I want—all fighter pilots want—to engage enemy fighters.

Captain Lewis hands the pointer to the group weather forecaster, Captain Mort Schmucker, who has a hard job. The standard joke is that “Air Force meteorologists are 100 percent accurate…50 percent of the time.” Schmucker says: “The target area is projected to be clear with the possibility of some thin cloud cover moving in easterly around midmorning. You should have 10-15 mile visibility at target bombing altitude….We’re forecasting clear all the way in at altitude…and back here over England we’re expecting some possible low scud beginning early afternoon.”

He’s doing his best, we know. But in 1944 there are no weather satellites or Doppler radar enabling accurate prediction of wind speed and direction, cloud cover, where storm conditions are building, where they’re subsiding, etc. Unforeseen bad weather can be a serious problem.

“We take off at 10:05,” Sluga tells us. “Check your watches. It is exactly…9…and …20…now! Good luck.”

Outside we pause for prayers. Around midpoint in my tour I stopped praying, having noticed none of my squadron leaders joined in. I also noted that some of those who had prayed most fervently got killed. I saw that praying gave comfort, but no favor whether one lives or dies. I also knew my mom was praying for me—and she had surely earned more points with God than I. And weren’t the Germans praying to the same God as our side?

In the Ready Room

Checking the schedule board, I find that I’m in Yellow flight today, flying Yellow 2 off Captain Fred Haviland’s wing. Yellow 3 is Lieutenant Barney Barab. His wingman is my barracks mate Lieutenant Charley Kelley, Yellow 4.

We fly as a team in combat until necessity separates us. Each pilot is responsible for his flight’s welfare, with the flight leader loosely in charge. The wingman’s primary responsibility is to protect the pilot off whose wing he’s flying, so he can focus on shooting, knowing his back is covered (No. 2 covers No. 1, No. 4 covers No. 3). The wingman flies to the side and slightly to rear of the pilot he’s protecting, covering his blind spot, his tail—and vice versa, as necessary. Improvisation is vital.

The mood in the ready room seems nonchalant, but I know we’re all thinking about the mission—fuel supply vs. target distance and estimated time in the air, who’s in my flight, my position in the flight, target flak. But there’s no talk about enemy fighters. No need: They’re why we exist.

I hang up my jacket and .45, and take my flying gear from my locker. First I put my escape kit (containing K-rations, aspirin, water purifier, matches, razor, dime-size compass, etc.) into my flight suit’s left leg cargo pocket and zip it shut. Then I put on my third pair of socks and re-lace my shoes. Next I zip myself into my G-suit, which fits from waist to ankles. I strap on my pistol and don my jacket.

I tie the straps of my Mae West inflatable life jacket over my A-2, put on my helmet (with attached RAF flat-plane goggles and radio intercom earphones) and clip it to my oxygen mask with microphone inside and connector hose. I put on three pairs of gloves: chamois, silk and finally leather gauntlets. Then I strap on my parachute harness, which has a first-aid kit sewn onto the right shoulder strap, leaving the leg straps loose so I can still walk. I’m now maybe 40 pounds heavier, ready to waddle out to the jeep that’s taking me and eight or nine others to our planes.

On the Flight Line

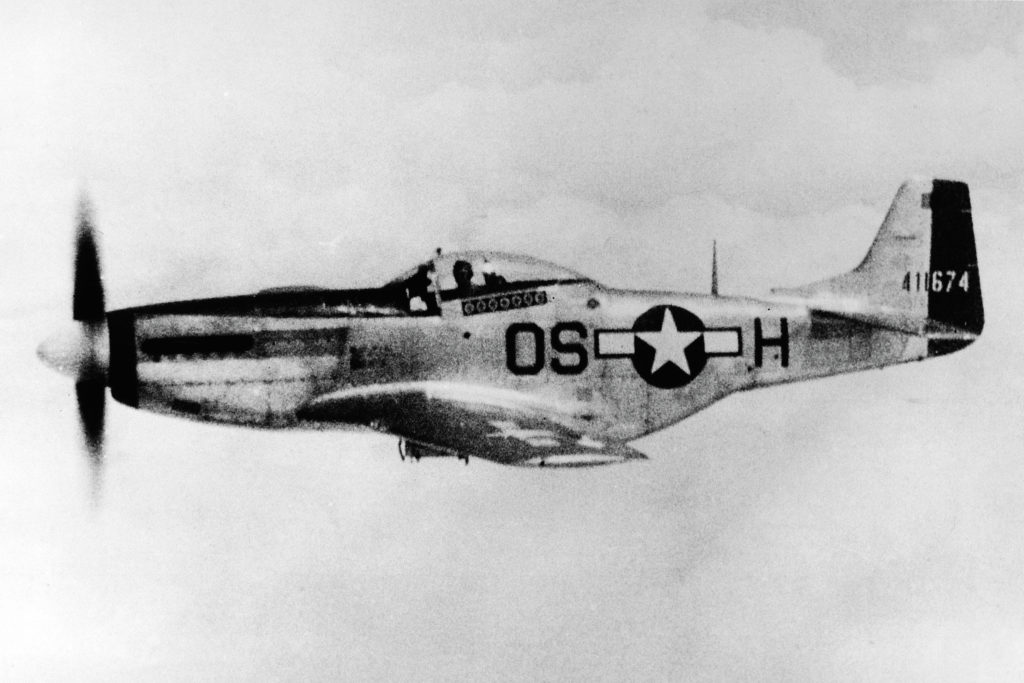

The Mustang I’ll be flying belongs to another pilot who’s not on duty today. (Soon after this mission I’ll get my own, a P-51D that I name Tiger’s Revenge for my cousin, Major Sylvan Feld, CO of the 373rd Fighter Squadron, Ninth Air Force, KIA in France.) I climb up on the wing, clip my parachute leg straps to the seat harness and slide into the cockpit. Space is tight even though I’m small (5 foot 6, 125 pounds). I adjust the seat full-high for maximum forward visibility and so I can see over the front and back of the wings. I also adjust my position relative to two rearview mirrors atop the forward windscreen, facing rearward 30 degrees left and right (these are excellent additions, put on by Steeple Morden crew chiefs).

The crew chief plugs my G-suit hose into its cockpit floor receptacle and also the hose leading to my oxygen mask. I hook up the earphone wire from my helmet into 355th Group’s intercom radio frequency. Then I wigwag the joystick to check the right and left wing ailerons, check the tail elevators by pushing the stick back and forth, and push on the rudder pedals right and left, to check the tail rudder. I also confirm that the fuel selector is feeding from the internal rear fuselage tank for takeoff, and the two internal wing tanks are full. Of course, the crew chief has already checked it all out beforehand.

There are no gauges for the two 110-gallon external wing tanks. Pilots have to estimate their use-up rates during each mission. My method is to run off each external tank, switching them every 15 minutes on the way to the target—to keep from flying right- or left-wing heavy—and use all the gas I can from the two externals before drawing on the internal tanks. The internal tanks are strictly for combat and getting home. Before combat, I must jettison both externals and switch to an internal tank, so that the Mustang can compete with Messerschmitt Me-109s or Focke-Wulf Fw-190s. With external tanks still attached, the P-51 is slower and less maneuverable, a sitting duck.

When an engine is running on an external tank, it stops when there’s no more fuel. The pilot must instantly switch to an internal tank, then lower the fighter’s nose to hold airspeed and keep the prop rotating, so the engine can restart and pull gas from the internal tank. Once you learn this lesson, you never forget it.

After I pull my seat belt tight, the crew chief tightens it further. I shake his hand and say, “Thanks a lot.” He nods, does a thumbs-up and jumps down off the wing. I switch the engine on, and the 1,650-hp Rolls-Royce kicks in with its distinctive roar. I eyeball all the instrument readings one more time, then wave for the chocks to be removed and slip in behind Fred Haviland’s Yellow 1 on the perimeter track.

Takeoff

As the 50 355th P-51s taxi toward takeoff, several hundred other Eighth Air Force fighters are doing the same thing at bases all over East Anglia. We will catch up with the roughly 1,000 B-17s and B-24s already heading toward Germany.

While taxiing, I adjust flaps 10 degrees down, to get extra takeoff lift for my fully loaded P-51 (469 gallons of gas and 1,750 rounds for six .50-caliber machine guns). Fred and I line up on the taxi strip behind Captain Henry Bille’s 357th Red flight, which is behind the last of Sluga’s four 358th Squadron flights.

Sluga (piloting Slugger) and his wingman are on the runway, watching for the tower’s rocket signal. At exactly 10:05 the signal goes up, and the 358th’s Red 1 and Red 2 zoom down the runway, followed by Red 3 and 4. Every 10 seconds a pair takes off, on through the Yellow, Blue and Green flights.

Now it’s the 357th’s turn. Bille and his wingman, Red 1 and 2, start out, followed by Red 3 and 4, as Fred and I roll onto the runway. I push fuel mixture to full rich and propeller pitch to full forward. We hold until we see Red 3 and 4 lift off, and then Fred pours it on and I throttle to redline, staying tucked in close to him as we lift off. Within about four minutes the entire 50-plane 355th Group is airborne.

Our three squadrons form up in V-formation flights, following group leader Sluga toward the rendezvous point at Ijmuiden. On the way up I check and recheck every instrument, hearing every imaginary engine roughness. I put on my oxygen mask at 8,000 feet. The supercharger automatically kicks in with a jolt at about 15,000 feet, adding extra power.

The Mission

Ijmuiden comes into sight right on time. Our box of B-24s is there at 26,000 feet, leading the bomber stream into Germany. The 355th flights then move from close V formations to spread-out-wide combat formations—standard procedure entering enemy territory. We slide about a quarter mile apart between planes, with roughly half a mile separation between flights.

As expected, anti-aircraft fire comes up from the Dutch coast. We fighters jink back and forth to throw off the Germans’ aim. We also radio warnings to whoever can’t see flak bursts creeping up behind them. Meanwhile the bomber stream plows straight ahead through the flak.

We parallel the bombers’ preplanned feints, which attempt to mask which city is our target. Our speed is twice theirs, and we zigzag at a cruising speed of about 250 mph over our B-24 bomber box from one flank to the other. Fighter groups fly near the bomb group they are assigned to. German fighters usually bunch up to attack the bombers when they find a gap in the fighter screen—or whenever they outnumber us.

Our 357th Squadron is positioned at the bomber stream’s head. As we near the Dummer Lake landmark, I look back, noticing that the stream, with escorts, stretches all the way back to the Dutch coast, about 100 miles’ distant.

We’re about 12 minutes from Misburg. The 357th’s Red flight is arrayed to the right of our bomber box, and my Yellow flight is to the right of Red, with the Blue and Green flights to the left a mile behind us. Someone calmly radios, “Bogeys at 10 o’clock” (bogeys are unidentified aircraft; bandits are enemy aircraft). Another calls, “Bogeys, 2 o’clock high.” I can see little black dots ahead, and then I hear, “Bandits, 12 o’clock!” followed by “Bandits at 3!”—Kelley’s voice. The dots rapidly enlarge and multiply across the horizon. They expand into 75 to 100 Me-109s, closing fast on the front of the bomber stream.

I quickly switch to the rear internal tank, drop my two external tanks and flick on the gun switch. Fred jettisons his externals and pivots right, toward 1 and 2 o’clock, where the gaggle of Germans is densest. We head into them full throttle—our combined closure speed some 600-700 mph—and go right through them, both of us narrowly avoiding crashing into enemy fighters. Our guns are firing, though I see no hits.

When Fred whips back, I’m glued to his tail, right behind and to one side. Now Fred’s firing at a 109 that’s in a diving turn under the bombers, following him down while hitting him. Trailing heavy smoke, that one’s done for. Out of the corner of my eye I see a bomber burst apart, and tiny forms falling out. No parachutes are opening. Fighters from both sides are swirling contrails all over the place. Then another bomber falls, with black smoke coming from the left-wing engines. Fred latches onto another 109, both of them diving and twisting down until the 109 loses half its right wing. That’s two for Fred. We’re down to 5,000 feet. My heart is pounding, and I’m drenched in perspiration.

On the radio we hear urgent shouts and warnings, some sounding close, others way off. More enemy fighters are hitting the bombers, though I can’t see them. Just now the sky seems empty of planes except our Yellow flight and the bomber stream far above us.

Suddenly Kelley yells, “Yellow 2, SIX!” I pull back sharply and left, then I hear Barney Barab slowly saying, “I…got…him.” Looking back, I glimpse Barab following down a smoking Me-109, with Kelley trailing them. Then it hits me: Yellow 3 and 4 just saved my life.

Tragedy Strikes

As we climb back toward the bomber stream, a 109 dives straight down almost directly ahead of us. Fred does a split-S to follow him, and during our dive we spot three more 109s on the deck, heading east. Fred corkscrews toward the trailing plane, with me following, but his dive is too steep and he has to pull out early. His target whips to the left while the leading 109 below turns right and comes in behind Fred, shooting up at him 200 to 300 yards ahead of me at about 30 degrees. I fire, landing many strikes on the German. There’s smoke and the 109 goes out of control, crashing into the deck. The rest of the 109s then disappear, heading east.

I follow Fred’s low, climbing circle, and we’re joined by Yellow 3 and 4. At 500 feet Fred turns due west: We’re heading home.

Kelley is flying funny, though his speed seems OK. Engine oil blackens his fuselage, but we can’t tell whether there’s damage to his plane. Now he drifts off formation, shifting erratically. Something’s wrong. The three of us radio him, but there’s no answer.

Barab goes in close to take a look. Suddenly Kelley swerves into him, and they both explode in a cloud of aluminum confetti! No possibility of survival. Horrible.

Fred and I circle around the silvery shards slowly floating down, looking for any positive sign, but we see nothing hopeful. We head toward home in a grim mood. Our transit over Germany to the North Sea coast is uneventful, though there’s flak over the Frisians. Fred and I are first ones back. I tell my crew chief about Kelley and Barab so he’ll tell their crew chiefs not to expect them.

Debriefing

Back at the ready room Poyen debriefs us separately. Neither he nor anyone else shows any surprise about Barab and Kelley. Some make brief comments, or shake their heads sadly. Losses are expected.

Of the original cadre of 28 men, only eight 357th Fighter Squadron pilots survive the war unscathed, a 71 percent loss rate. Of the 128 replacement pilots, 70 come through unscathed, a 45 percent loss rate. Subtracting those who were shot down and became POWs or evaders, one-third of all 357th Squadron pilots are killed in action in the war.

Gun-camera film later confirms that Fred destroyed two Me-109s and I destroyed one. I report Barab’s 109 shootdown, and Fred attests to it. We learn that there were 26 victories today for the 355th Group, versus three losses.

Fred later tells the others I was a “tiger” and saved him, the genesis of my nickname, “Tiger” Lyons. I tell everyone how Barab and Kelley saved me.

I’m credited with five hours’ mission time for the Misburg raid. My total now stands at 121 hours, 45 minutes, toward a required 300 combat hours before I’m eligible for a 30-day leave in the U.S.

The November 26, 1944, mission turned out to be one of the largest aerial battles of the war. Dogfights raged all along the bomber stream against 300-plus Me-109s and Fw-190s that day, with the Eighth Air Force Fighter Command claiming 121 victories for 10 losses. Although our bombers were hit hard, the oil refinery at Misburg was largely demolished.

I don’t feel up to the officers’ club ritual. Instead I write my mom about my day. Today’s lie is that I went to London again.

We’ve both been lying in our letters. I say I’m going to London, or at the club playing ping-pong or billiards, or watching a movie. And mom always asks what she can send me, but never mentions she has a job at the Brooklyn Army Base—to put aside money “for when Billy goes to college.” A couple of weeks after today’s mission, the “Home Talk” column in our Brooklyn newspaper runs my picture and reports that I shot down an Me-109. Mom gets phone calls, but she’ll never write a word to me about it—or about my next shootdown, which gets mentioned in The New York Times.

Coming back to my bunk after a bath, I see that Kelley’s mattress is already folded over. Awfully fast, I think, but it’s the usual.

I write mom that today I saw Buckingham Palace. Then I write to Kelley’s parents. He was such an outgoing, warm, friendly guy. A good, brave man. My friend. I can still see him in my mind, hear him warning me, “Yellow 2, SIX!” I rewrite the letter several times.

On the way to dinner, I pass Captain Poyen, who tells me I’m not on tomorrow. Maybe I will go to London.

William Lyons completed his 300-combat-hour tour on March 28, 1945, ending the war as a flight leader with 63 missions and the Distinguished Flying Cross, Air Medal with eight Oak Leaf Clusters, five ETO Battle Stars and two Presidential Unit Citations. An extended version of his Misburg mission account will appear in Our Might Always, Vol. 1, by William Marshall, due from Schiffer this spring.