On July 3, 1940, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill had to make one of the most momentous decisions of his career. Early that morning, he ordered a British fleet to arrive off the naval base of Mers-el-Kebir in North Africa and demand the surrender of the French vessels there. The British were to offer the French admiral four alternatives intended to prevent the French fleet’s falling into the hands of the Germans. If the French commander refused the terms, his ships would be sunk by the British force. If the British were compelled to open fire, it would be the first time in 125 years that the two navies were arrayed against one another in hostility.

In order to prevent an Anglo-French showdown, Churchill and the British War Cabinet worked feverishly throughout the month of June to arrive at a diplomatic settlement of the problem. Efforts to gain valid assurances from the French that their ships would be denied to the enemy did not produce satisfactory results. Ultimately, negotiations failed and Churchill had to resort to force in order to protect Britain from the ‘mortal danger that Axis possession of the French vessels threatened. Although an attack would certainly incur the enmity of France, the urgency of the situation left Churchill with no option but to turn the guns of the Royal Navy against his recent ally.

In June 1940, Great Britain was in a precarious strategic position. With the collapse of French resistance imminent and the sudden entry of Italy into World War II, Britain suddenly found herself standing alone against Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich. Almost overnight, all of Europe was either at war with England or under the control of her enemies. The situation that now confronted Britain was far worse than the one she had faced in 1917.

Within a fortnight of Italy’s entry into the conflict, the balance of naval power in the Mediterranean shifted against the British. With France out of the war, Britain had to assume naval responsibilities throughout the whole of the Mediterranean. Stretched dangerously thin, Britain might have to abandon her considerable interests in the eastern Mediterranean and concentrate her naval strength at Gibraltar. Facing the prospect that the Royal Navy might have to confront the combined German-Italian fleet alone, Churchill ordered substantial reinforcements to the Mediterranean from other trouble spots throughout the empire.

While these reinforcements temporarily redressed the balance in Britain’s favor, the question of what was to become of the vessels of the French fleet was a source of intense anxiety for the War Cabinet in London. In 1940, the French fleet was the fourth largest naval force in the world after Britain, the United States and Japan. Its strength included seven battleships, 19 cruisers, 71 destroyers and 76 submarines. Shortly after the Germans attacked France on May 10, 1940, most of the vessels in French ports sailed to other harbors. A powerful French naval force was anchored at Mers-el-Kebir, just to the west of the French Algerian port of Oran.

Churchill knew that the French warships could not be allowed to fall into the hands of the Axis. If Germany and Italy could add these units to their existing naval force, Britain would face an overwhelming threat that it could not adequately meet. With Britain’s command of the seas in jeopardy, the British Isles could be cut off from the rest of the empire and the vital Atlantic supply routes irrevocably closed. In addition, the waters around the British Isles could become an unobstructed avenue for a German invasion force.

In dealing with the French fleet issue, Churchill at first used tactful diplomacy and friendly persuasion. Despite Churchill’s numerous requests that the French immediately sail their ships to the safety of British ports, the government of French Prime Minister Paul Reynaud, and later the Vichy regime of Marshal Philippe Petain, refused.

Britain’s general distrust of French intentions was heightened on June 20, when Petain violated a no separate peace agreement with Britain and concluded an armistice with Germany. The terms of the treaty dealt a serious blow to British interests. One clause in particular, Article Eight, appeared to be most threatening. This stipulated that all vessels outside of home waters were to immediately return to France. In North Africa, the French fleet was at least a few hundred miles from the nearest German-controlled territory. If compelled to sail to occupied France, the vessels would come within Germany’s grasp.

On June 24, with no clear solution to the French problem in sight, the War Cabinet met in three extraordinary sessions. While no final course of action was agreed upon, the consensus was that something must be done to gain immediate control of the French warships or to permanently put them out of action. The next day, the War Cabinet instructed Vice Adm. Dudley North to proceed to Oran and meet with the French naval commander there, in order to gauge his views on the situation. The admiral flatly refused to hand over his ships to the British under any circumstances.

The realities of the British military situation necessitated an urgent settlement of the French problem. As Churchill pondered, Germany was poised in the Low Countries and along the coast of France, ready to intensify its attack on the convoys carrying vital supplies to Britain. German bombing raids were already a frequent occurrence in many of Britain’s southeastern cities. In Berlin, Hitler was completing plans for the invasion of Britain–Operation Sea Lion.

To meet the invasion threat, the overriding concern for Churchill and his advisers was to concentrate the maximum possible naval strength in home waters. The uncertainty regarding the French fleet had to be dissipated as soon as possible in order for the British warships now shadowing the French to be released for operations elsewhere.

Because Britain was militarily inferior to her enemies, her only hope of survival during a protracted war was persuading outside powers to intervene on her behalf. Unfortunately, the predominant world opinion was that Britain would soon collapse.

Something had to be done to counter this pessimistic appraisal of Britain’s chances and to enable the country to break out of its state of diplomatic isolation. Churchill felt that since many people throughout the world believed Britain was about to surrender, a bold stroke in British foreign policy was needed to impress upon the world Britain’s determination to continue the war and fight to the end. With one audacious move, he believed all doubts could be swept aside by deeds.

On June 27 the War Cabinet met to plan that decisive action. With the very life of the state at stake, Churchill set July 3 as the day on which all French naval warships within Britain’s grasp would either be seized or destroyed. For the next six days, the War Cabinet and naval staff worked on the details of Operation Catapult.

In choosing primary targets, the planners felt that little was to be feared from the French ships that had taken refuge in Britain’s home ports. The planners figured that they could seize these ships–which included the powerful old battleships Courbet and Paris, the large destroyers Leopard and Le Triomphant, the smaller destroyers Mistral and Ouragan, and the huge submarine Surcouf–at their convenience. Likewise, there was no immediate concern about seizing formidable French battleship Jean Bart at Casablanca or Richelieu at Dakar, West Africa. Both vessels were being kept under close surveillance by an adequate number of British warships. Similarly, the three older battleships and one light cruiser at Alexandria, Egypt, could easily be neutralized by Admiral Sir Andrew Cunningham’s force stationed there.

The real concern of the War Cabinet was what to do about the French ships at or near Oran. There the situation was very different. The large port in northwestern Algeria was home to a modest force of seven destroyers, four submarines and a handful of torpedo boats, and at the nearby base of Mers-el-Kebir, under the protection of powerful shore batteries on the cliffs above, lay anchored the strongest concentration of French warships in the world. These ships were from the mighty Atlantic fleet (Force de Raid) and had moved to Mers-el-Kebir from Brest, France, in early June. The force included the battleships Bretagne and Provence, six destroyers, one seaplane carrier and two modern battle cruisers, Dunkerque and Strasbourg. In 1940 naval power was reckoned on the basis of capital ship strength, and these two Dunkerque-class battle cruisers were a major concern for the British Admiralty. Dunkerque, which had been launched in 1937, was one of the most modern ships afloat. She was armed with eight 13-inch guns and capable of cruising at 291Ž2 knots. Strasbourg had been commissioned in 1938 and possessed similar assets. Both vessels were more powerful than the German Scharnhorst and Gneisnau and faster than anything the British possessed except the battle cruiser Hood. Provence and Bretagne were each capable of 20 knots and carried 10 13.4-inch guns.

Commanding the French fleet at Mers-el-Kebir was a highly disciplined and efficient admiral, Marcel Gensoul. In British Captain Cedric Holland’s assessment, Gensoul was completely service. He was fervently loyal to the French naval commander, Admiral of the Fleet Jean François Darlan, and to the Vichy government. According to Holland, Gensoul was known to be somewhat pigheaded and difficult to deal with. In addition, the admiral’s bitter anglophobia was well-known in British naval circles. The prospects for obtaining his cooperation through verbal persuasion did not seem to be encouraging.

On June 27, the War Cabinet discussed the best way to eliminate the menace posed by the vessels at Mers-el-Kebir. Churchill’s main concern was that the ships be contained within the harbor and then neutralized within a short space of time. As a means of accomplishing this, he planned to have a British force arrive off Mers-el-Kebir and offer Gensoul four alternatives–have the French fleet join the Roayl Navy, take the fleet to British ports with reduced crews, take the fleet to a French West Indian port or a U.S. port and be decommissioned, or sink the fleet right there in Mers-el-Kebir’s harbor. If none of those options were accepted within three hours, the British admiral on the scene would be instructed to sink the French fleet by naval gunfire.

Later that day, the War Cabinet informed Vice Adm. Sir James Somerville that he was to command Force H, a flotilla that had been hastily formed to monitor the situation in the Mediterranean. Now it was to be the main instrument in a large-scale operation that would effectively place the French fleet permanently beyond the enemy’s reach. The British had assembled an impressive array of firepower. At Somerville’s disposal were the battle cruiser Hood, the battleships Valiant and Resolution, the aircraft carrier Ark Royal, the smaller cruisers Arethusa and Enterprise and 11 destroyers.

At 3:30 p.m. on June 29, Somerville was briefed on his task. He was to endeavor to secure the transfer, surrender, or destruction of the French warships at Oran and Mers-el-Kebir by any means possible, and no concessions were to be given to the French. They were either to accept the British terms or face the consequences.

On July 2, Somerville received his final instructions and held a conference aboard his flagship in which he briefed his staff on Operation Catapult. Persuasion and threats were to be employed first, in an attempt to get Gensoul to comply. If he refused to accept any of the alternatives, the British were to fire a few rounds close to the French ships. If Gensoul still remained intransigent, Force H was to destroy the French fleet as efficiently and with as little loss of life as possible.

At 5:30 a.m. on July 3, Somerville’s task force arrived off Mers-el-Kebir. The British commander had been instructed to complete the operation during daylight. At 6:30 a.m., the destroyer Foxhound steamed toward the harbor entrance with Captain Holland on board. Holland had been instructed to meet with Gensoul and personally explain the British terms to him.

At 8:10, Gensoul sent Flag Lt. Antoine Dufay in a launch to confer with Holland. Holland told the lieutenant that it was of the utmost importance that he speak directly with Gensoul about his mission. Dufay replied that Gensoul had refused to see the British captain.

Meanwhile, Gensoul, surveying the scene before him, grasped the significance of Force H and became indignant at what he felt was likely to be British diplomacy at gunpoint. At 8:47, he ordered Foxhound to leave the harbor at once.

Holland, knowing what would happen if negotiations failed, tried once again to see Gensoul. Pretending to exit the harbor, the determined Briton instead boarded a fast launch and sped toward Gensoul’s flagship. Before he could get there, he was intercepted by Dufay in another craft. Dufay again explained that Gensoul would not see him. In desperation, Holland handed the flag lieutenant a briefcase containing the text of the British terms. The British had planned to communicate these demands orally, but Gensoul’s stubbornness precluded that option. Since Force H was to take action before sundown, Holland felt it was imperative to deliver the terms by any means possible.

Gensoul had read the British demands, he became incensed. At 9:45 he signaled the French Admiralty in Toulon, informing them that a British force was off Oran and that he had been given an ultimatum to sink his ships within six hours. Gensoul transmitted his intention to reply to force with force.

While Holland was awaiting a reply aboard Foxhound, he reported observing the French vessels beginning to unfurl their awnings and raise steam. It was clear that the French were preparing to leave the harbor. First Sea Lord Sir Alfred Dudley Pound ordered Somerville to have the harbor entrance sown with mines in order to prevent the fleet from leaving.

At 10 a.m., Somerville received a message from Gensoul that, in view of what amounted to a veritable ultimatum, the French warships would resist any forcible British attempt to gain control of the fleet. Gensoul informed Somerville that The first shot fired at us will result in immediately ranging the entire French Fleet against Britain. Since Gensoul had refused the terms and was apparently preparing to fight, Somerville told the British Admiralty that he would begin firing at 1:30 p.m. Still undaunted, Holland was convinced that a peaceable settlement could be found, and he implored the Admiralty for more time to negotiate. As a result, there was delay after delay during the next three hours, and a new deadline was set for opening hostilities–4:30 p.m.

At first this approach seemed to pay off. At 4:15, Gensoul relented and agreed to parley with Holland. While this appeared to be an encouraging development, the mood of optimism was soon dampened. Gensoul told Holland that so long as Germany and Italy abided by the armistice terms and allowed the French fleet to remain in French metropolitan ports with reduced crews, he would also remain. While the meeting was taking place, the harbor was mined. The French admiral viewed this as a hostile act, and it added to the tension of the interview. At times it seemed to Holland that an agreement was in sight, but it was becoming painfully clear to the British that Gensoul was merely stalling for time.

In the meantime, the situation was becoming more and more hazardous. The misleading signal that Gensoul had sent at 9:45 had reached the French Admiralty. In the absence of Darlan, who could not be located, the French chief of staff, Admiral Le Luc, issued a response in his name. He told Gensoul to stand firm and ordered all French naval and air forces in the western Mediterranean to prepare for battle and proceed with the utmost haste to Oran.

Before Gensoul could inform Holland of the orders he had received, the British Admiralty intercepted Le Luc’s order and passed it on to Somerville. The naval chiefs added, Settle matters quickly or you will have reinforcements to deal with. As a result, Somerville sent a signal to Gensoul, stating that: If none of the British proposals are accepted by 5:30 p.m., it will be necessary to sink your ships. That message–received aboard Dunkerque at 5:15 p.m.–put an end to all discussion. In view of the irreconcilable position of each side, further negotiation was fruitless. A disappointed Holland somberly departed the French flagship at 5:25. A few minutes later, before he had even cleared the harbor, Force H opened fire on the French ships. The first Anglo-French naval exchange since Trafalgar and the Nile had begun.

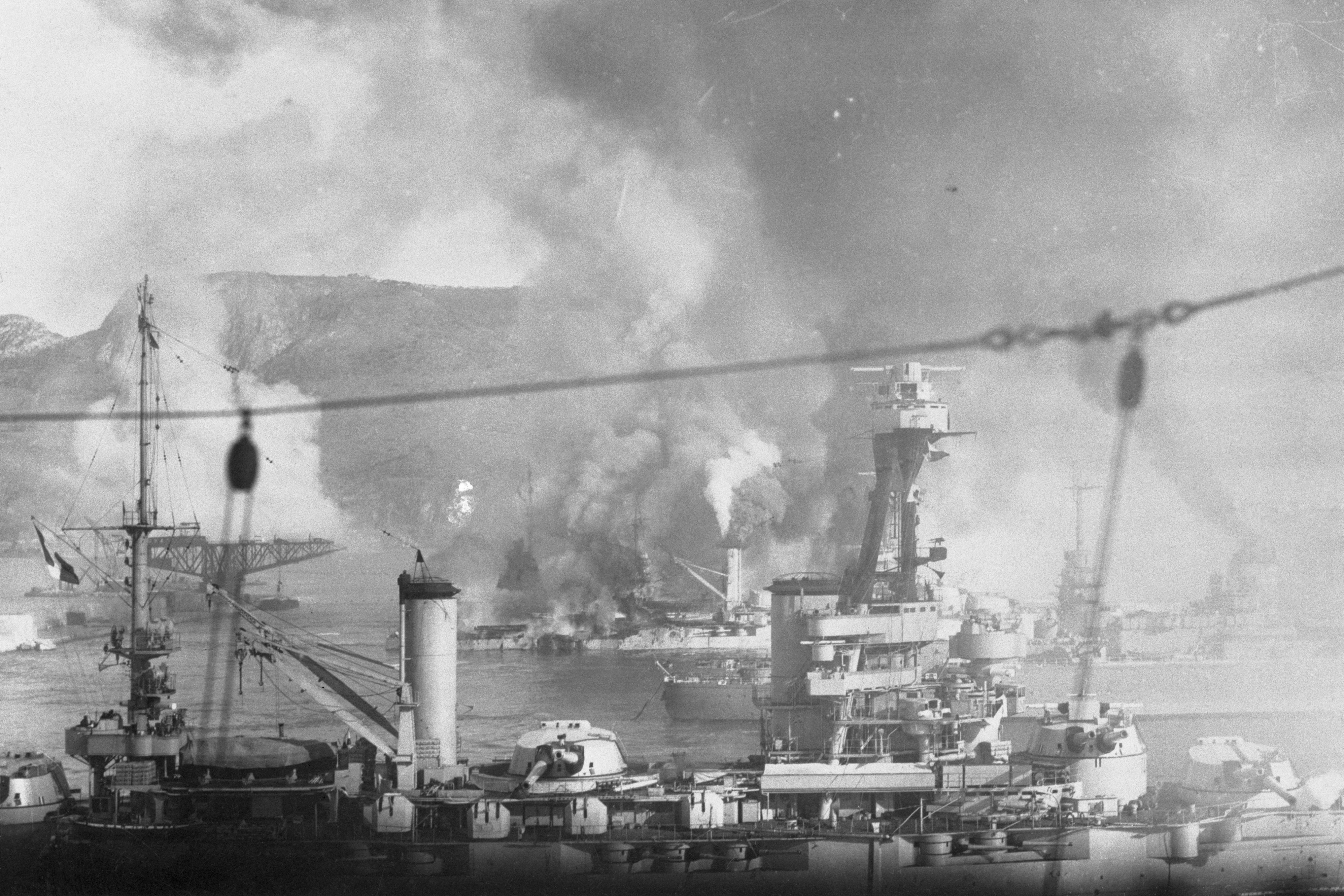

It was not much of a duel, for most of the gunfire came from the British. According to French Admiral Auphan, the British gunfire was very heavy, very accurate and short of duration. One of the first salvoes struck the battleship Bretagne, which blew up. Another shell tore off the stern of the destroyer Mogador. Dunkerque received several hits but managed to fire about 40 rounds at Hood before being put out of action. Heavily damaged, Provence was forced to run aground. Before the smoke cleared, the bulk of French naval power at Mers-el-Kebir was either aflame or at the bottom of the sea, and more than 1,297 French sailors had been killed.

In response to a signal from the shore begging the British to cease fire, Somerville ordered his guns silent. He gave the French an opportunity to abandon their ships in order to avoid further loss of life. But the French used the reprieve to make a break out from the harbor with the few undamaged ships remaining. As Force H moved westward to avoid exposure to the shore batteries, Strasbourg, the seaplane carrier Commandant Teste and five destroyers avoided the mines and escaped into open water. Somerville ordered three airstrikes against Strasbourg from Ark Royal. The British pilots scored a direct hit on the beleaguered Strasbourg, but the vessel managed to continue her escape. On July 4, the meager force that had escaped Mers-el-Kebir arrived in Toulon. Doubts about the extent of damage to Dunkerque led to a dawn torpedo attack by British Fairey Swordfish bombers the next day, which effectively put Dunkerque out of action.

There can be little doubt that the effect of the attack on Anglo-French relations was entirely negative. On July 3, the French chargé d’affaires formally protested the British action. For a while it seemed possible that the French might have been provoked to the point of declaring war. Immediately after the attack, Admiral of the Fleet Darlan ordered all French warships to engage the British enemy wherever they were encountered. On July 5, a small squadron of French aircraft appeared over Gibraltar and dropped some bombs on British installations there, causing minor damage. On July 8, the Vichy government officially severed all diplomatic ties with London.

While the goodwill of France had been sacrificed, the material results of the operation were considerable and seemed in themselves to justify Churchill’s use of force. Strasbourg and five destroyers had eluded the British efforts to sink them, but the bulk of France’s capital ship strength had been effectively neutralized. In the space of a few hours, the world’s fourth largest fleet had lost 84 percent of its operational battleship strength and had been reduced to a token force of light craft and submarines. As a result of the action at Mers-el-Kebir and seizures elsewhere, Britain had successfully eliminated the danger of an augmented Axis fleet, while reaffirming its own naval supremacy.

Perhaps an even more important consequence of Churchill’s action was the favorable impression it created on world opinion. Catapult was a striking example of Britain’s determination to continue the war at all costs and despite the odds. While the aggressive ruthlessness of the Royal Navy proved crucial in gaining the confidence of many of the neutral powers and the respect of the enemy, it was the new position of the United States that was the most significant.

President Franklin Roosevelt lauded Churchill’s action and welcomed it as a service to American defense. To other American officials as well, Catapult eradicated all doubts of Britain’s ability to repel an enemy invasion. This newfound confidence translated into material benefits for Britain as FDR pressured Congress to step up support through Lend-Lease and the Destroyers for Bases arrangement.

The British attack on the French fleet at Mers-el-Kebir was a major turning point in World War II. As Britain braced herself for the upcoming duel with Germany in the skies and on the sea, the vital commitment of the United States would weigh heavily in the balance. Without the moral and materiel benefits that were gained from Churchill’s bold stroke at Oran, the Axis domination that had descended upon the free world by 1940 might never have been broken.

This article was written by Robert J. Brown and originally appeared in the September 1997 issue of World War II magazine. For more great articles subscribe to World War II magazine today!