A gateway between the North and the South, this transportation hub was coveted territory for commanders on both sides.

When the pavement beneath your feet begins to rumble and the whistle of another passing freight train pierces the silence of this sleepy town, it’s easy to understand how the antebellum city of Martinsburg, Va. (now West Virginia), prospered as a major transportation center due to its location along the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. Martinsburg was the Shenandoah Valley’s second largest town, with a population of more than 3,360. Its fortune before the war, however, would be its downfall during it. Strategically located as a gateway between the north and south, the Union and Confederacy contested for it frequently and it changed hands nearly 40 times, though its residents remained stubbornly unionist even as the state seceded. In May 1861, General Joseph Johnston ordered then-Colonel Thomas J. Jackson to destroy the rolling stock in Martinsburg, a task he began begrudgingly in June, burning 300 cars and destroying 42 locomotives. “It was sad work,” he wrote his wife, Anna, “but I had my orders and my duty was to obey.” In October 1862, after the Battle of Antietam, Jackson returned to Martinsburg as he destroyed more than 20 miles of track between Harpers Ferry and North Mountain, 17 bridges, and more than 100 miles of telegraph wire. This time, without hesitation, he ordered the burning of the town’s roundhouses and all its shops, as well as the rail yards. Several skirmishes and battles were fought in the area, including as part of the Gettysburg Campaign and one on July 25, 1864, as part of Confederate General Jubal A. Early’s summer campaign in the Shenandoah Valley. Martinsburg was also home to notorious Confederate spy Belle Boyd, whose house is now a museum. Visitors to the area can see the rebuilt roundhouse, peruse shops along the tracks, and follow battle actions via Civil War Trails signs posted around town.

[hr]

The Roundhouse

136 East Race Street

In June 1861, the future “Stonewall” Jackson, under orders from General Joseph Johnston, stripped Martinsburg’s Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Roundhouse and Shop Complex of all the stationary equipment, tools, and a 40-foot turntable. The roundhouse itself and shops suffered only minor damage. When Stonewall returned in October 1862, after Antietam, he dared not leave anything of use for the Federals and ordered all the buildings burned. The roundhouse complex standing today was rebuilt after the war, beginning in 1865, and includes two roundhouses, the Bridge and Machine Shop, and the Frog and Switch Shop. Saturday tours are offered April through October from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m.

[hr]

Belle Boyd House

126 East Race Street

One of Martinsburg’s most memorable residents, Confederate spy Belle Boyd, lived at this address for part of her childhood. Boyd most famously supplied Stonewall Jackson with information about enemy activities. She was imprisoned twice for espionage before being banished to England. Benjamin R. Boyd, Belle’s father, built this Greek Revival–style house in 1853. When it was threatened with demolition in 1992, the Berkeley County Historical Society rescued it. The Society now operates the Belle Boyd House as a museum.

[hr]

117 East Race Street

When the Confederates burned Martinsburg in the aftermath of the Battle of Antietam, the antebellum Berkeley Hotel was one of the only buildings spared. The B&O Railroad bought the building in 1866, expanded it, and used it as the station, eating house, telegraph office, and hotel. In 1877 the trainmen and enginemen here struck to protest wage cuts, starting the “Great Strike of 1877” nationwide. Railroad and military officials suppressed the strike here, using this building as headquarters. Today it serves as the town’s Visitor’s Center.

[hr]

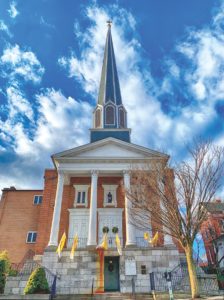

225 South Queen Street

Dedicated on May 30, 1860, the church here was used incessantly throughout the war, serving as a hospital and a stable. In the war’s aftermath, the church filed a claim with the Southern Claims Commission for fees to be paid for rent, as well as for damage done to the church’s structure and graveyard during the war. The church applied for nearly $4,000, but was awarded only $2,880.

[hr]

Green Hill Cemetery

486 East Burke Street

This 1854 cemetery was designed by Martinsburg resident, David Hunter Strother, who would go on to serve the Union during the Civil War in several capacities, including as a topographer. Among the graves are 30 unknown Confederate soldiers, as well as Captain E.G. Alburits, who commanded the Berkeley Company at Harpers Ferry during the John Brown raid. Strother and his family are also buried here.

[hr]

Colonnade Bridge Site

The historic colonnade-style bridge once carried the railroad tracks over Burke Street and Tuscarora Creek. Built in the 1840s, the colonnade structure was blown up in June 1861 as Confederates destroyed sites around town that could be useful to the Federals. Portions of the structure’s stonework columns, or abutments, still remain. Union General and future President Rutherford B. Hayes reportedly lain ill for several days in July 1864 in a nearby building.

[hr]

Battle of Falling Waters, July 2, 1861

The Shenandoah Valley’s first engagement of the Civil War broke out here on July 2, 1861, on the farm of William Rush Porterfield. Under orders to delay Confederate troops amassing near Manassas, Union General Robert Patterson and about 3,500 troops crossed the Potomac and attempted to pin Confederates in Martinsburg. Then Colonel Thomas Jackson ordered the 5th Virginia Regiment, about 380 men, and one cannon along the Valley Turnpike to meet them. Outnumbered and outgunned, the Rebels retreated after 45 minutes of fighting, but Patterson, believing he had matched up against a larger Confederate force than was present, was more cautious thereafter, allowing Confederates to regroup and move out towards Manassas. The battle, named for the waterfalls located along the turnpike, was a Union victory, but strategically a victory for the Confederates who three weeks later would claim a victory at the First Battle of Manassas, in part because of reinforcements from the Martinsburg area.

[hr]

McFarland House

409 South Queen Street

This 1878 home was beautifully restored and now serves as a restaurant and wedding or event venue. Locals and visitors especially enjoy the McFarland House Sunday Brunch featuring breakfast and lunch favorites including crepes, french toast, lobster bisque, and more. Reservations are suggested.

This story appeared in the May 2020 issue of America’s Civil War.