What American-made aircraft served in the armed forces of 55 nations in a wide variety of roles such as primary, basic or advanced trainer, fighter, bomber, attack, transport, tow target, photographic and observation plane? What aircraft served in the U.S. Air Force and Navy and fought in a dozen wars, including World War II, Korea and Vietnam? What aircraft and its many variants were known as the Texan, Mosquito, Harvard, Yale, Wirraway, Boomerang and Tomcat?

There is only one answer: the North American single-engine, two-seat aircraft known first in the U.S. Army Air Corps as the AT-6 (later T-6) and in the U.S. Navy as the SNJ. The manufacturer dubbed it the Texan. The other names, except Mosquito, were given to it or its variants by the British, Australians, Canadians and French. Mosquito was a nickname given to the plane in Korea by American pilots when it was used as a target-spotting aircraft.

There were 17,096 Texans of all models built by North American Aviation Co. and the foreign companies licensed to produce them. Not only did they serve in the wars mentioned, but they also saw combat in the war between Ecuador and Peru in 1939 and in the Israeli 1948 War for Independence. They were used in the war between the British and Malaysian terrorists during 1948–1951 and in a counterinsurgency role by the French in Algeria during 1954–1961.

Belgium used these aircraft in the war in the Congo, and they were flown by the Congolese during the 1960s against rebels in Angola, Mozambique and Portuguese Guinea. Former French T-6s were used in Nigeria during that country’s civil war of 1967–1970. One T-6 was credited with destroying a Soviet-built MiG fighter on the ground during a strafing pass. The last known use of the Texan in combat was by the Spanish air force against guerrillas in North Africa in 1975.

The Texan began life in 1935 as the NA-16, a prototype trainer designed by James H. “Dutch” Kindelberger, president of North American Aviation, Inc. It had two open cockpits and a fixed gear and was powered by a 400-hp engine.

In 1934 the U.S. Army Air Corps had issued specifications for an airplane “to provide a means of command liaison and command reconnaissance for Corps and Divisions, and to provide for the maintenance of the combat flying proficiency of pilots and observers.” Kindelberger and North American worked to secure the contract, and the NA-16 flew for the first time on April 1, 1935. The NA-16 was chosen over the competitors’ designs, but before ordering any NA-16s, the Air Corps required North American to enclose the cockpits with a sliding canopy, install streamlined fairings over the wheel struts and add wheel pants.

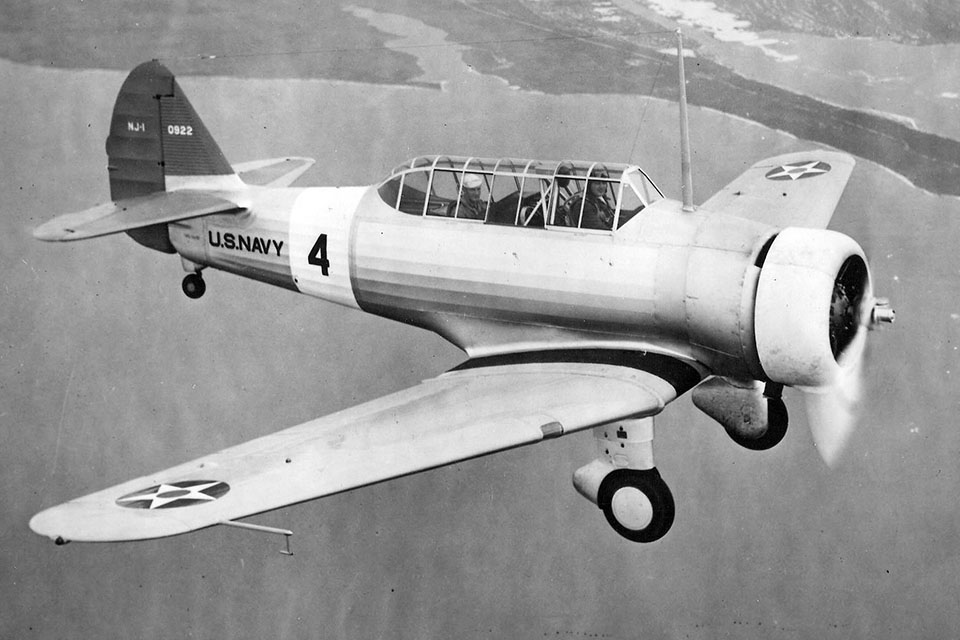

When the modifications were complete, the Air Corps ordered 42 under the company design number NA-18; the Air Corps called it the BT-9 (basic trainer, type 9). The first production model was flown on April 15, 1936. The Navy ordered 40 of them after the existing engine was replaced with a 500-hp version. That model was designated the NJ-1 (N for trainer and J for North American).

Several improvements were made as production proceeded. The BT-14 followed with a new wing design and other changes, and the Air Corps ordered more than 250 of them. Concurrently, the French ordered 230 of the BT-9/BT-14 models and called them Tomcats. When France was overrun by the Germans in 1940, Tomcats not yet delivered were given to the Royal Canadian Air Force and designated Yale Mark Is.

Next came the BC-1 (basic combat, type 1), which had the same basic airframe design as the BT-9 but with a retractable main landing gear. It was equipped with one nose-mounted .30-caliber machine gun that fired through the propeller and a second .30-caliber gun on a flexible mount in the rear cockpit. The first one flew on February 11, 1938. The Edward G. Budd Manufacturing Co. was subcontracted to experiment with stainless steel in the wing panels to determine its structural feasibility in the aircraft.

The Navy had been searching for a trainer for pilots destined to fly its scout aircraft, such as the Douglas SBD dive bomber, and it chose the BC-1. Sixteen were ordered with modifications to suit Navy requirements and designated the SNJ-1 (for scout trainer). Later, as refinements were made, the BC-1 designation was dropped by the Air Corps and replaced by AT-6 (for advanced trainer, type 6).

North American engineers designed two variants of the BC-1 to sell to overseas buyers as fighters and attack planes. One was a single-seat fighter and the other a two-seater; both had five .30-caliber machine guns in the wings and nose. The attack version also had a flexible machine gun in the rear cockpit. The first order, from the Siamese air force, was for 10, including both versions. Brazil, Peru and Chile ordered 49 single-seat fighters.

Siam never received any of the aircraft, however. Tension was increasing at the time between Siam and French Indochina, and the State Department prohibited the transfer. The aircraft were diverted to the Philippines, where they were taken over by the U.S. Army Air Corps. The fighter/attack two-seat version was then designated the A-27. Several A-27s saw action in the Philippines on December 8, 1941, against invading Japanese forces. The single-seat version was stripped of armament, returned to the States for fighter pilot training and designated the P-64.

The Navy later requested several modifications to the SNJ-1, including a more powerful engine. That changed the designation to SNJ-2. The Air Corps asked for other modifications, and the AT-6A/SNJ-3 emerged as the standard advanced single-engine trainer for both services. (It was used for basic pilot training and even for primary training toward the end of World War II, when Nationalist Chinese students were sent to the States for pilot instruction.)

To accommodate orders that amounted to more than 600 aircraft when war began, North American opened a new plant in Dallas in 1942 to supplement the aircraft being turned out in the Los Angeles area. The Dallas plant became the main point of manufacture—hence the name “Texan.” New model suffixes were assigned as minor changes were made. To save aluminum, some of the AT-6/SNJs were turned out with plywood fuselages and internal stringers made from spruce. The Navy added tail hooks for carrier training. Bomb racks and belly fuel tanks were also added.

A number of Texans were either built or modified for experimental purposes. The Army Air Forces ordered one XAT-6E in 1944 with an inline, air-cooled engine installed. On test flights it reached a top speed of 244 mph and climbed to 30,000 feet—50 mph faster and 6,000 feet higher than the Texans flying with radial engines. Unfortunately, the inline engine proved to be a maintenance headache, and only one XAT-6E was built.

Another experimental Texan was designated the ET-6F in 1950, when a swivel landing gear was installed to assist in making crosswind landings. The Northrop Co. experimented with autopilots in the T-6. Cameras were installed aft of the rear seat in a few aircraft for aerial photography; flares were added to make photography possible at night as well.

When the British realized they could not build enough trainers in the United Kingdom at the beginning of World War II, they ordered the BC-1, which they designated the Harvard Mark I. A single British machine gun for the right wing was specified, as well as British instruments and a circular control stick called a “spade.” The Canadians also ordered the Mark I, and one variant was labeled the AT-16. Since British engine mixture controls were reversed as far as Americans and Canadians were concerned, a warning plaque was installed that read: “This airplane has British carburetor mixture control. Lean–forward. Rich–back.”

The North American Aviation Co. granted rights to the Australians to manufacture the two-seat BC-1, which they called the Wirraway, a native word meaning “challenge.” It had twin machine guns in the nose, a flexible gun in the rear cockpit and could carry up to 500 pounds of bombs on underwing racks. The first Wirraways were rolled out in 1939. They saw heavy service during the first days of World War II as interceptors, fighter-bombers and long-range patrol aircraft, as well as observation craft.

One Aussie pilot, Flt. Lt. John Archer, received an award for downing an enemy aircraft with a Wirraway off the coast of Buna on December 26, 1942. Archer was flying patrol with Sergeant N.J. Muir over a wrecked Japanese freighter that was suspected of housing a radio station and lookout post. Looking down, he saw a lone Japanese Mitsubishi A6M Zero cruising along unaware of his presence. Although he knew the Wirraway was no match for the Zero, he dove on it anyway, fired his single machine gun and watched the Japanese plane plunge into the sea. It was later learned that he had killed the pilot with a single shot through the head.

The Australians also flew the single-seat version, calling it the Boomerang. It was armed with four .303-caliber machine guns and two 20mm cannons.

After World War II, the U.S. Air Force changed many of its plane designations, and the “A” was dropped from the Texan’s identification. The T-6s were extremely active during the Korean War as spotter planes. Their pilots were officially known as forward air controllers, but their planes were popularly called Mosquitos, since they harassed the Communist forces and specialized in locating enemy targets and guiding fighter-bombers in for airstrikes. They were also flown for air rescues and leaflet-dropping missions. Several were used as interceptors against the North Koreans, who were flying Soviet-made Polikarpov PO-2 night raiders. When remanufactured T-6s arrived with improved radios, underwing bomb and smoke-rocket racks and two pod-mounted machine guns, they were designated LT-6Gs. By the end of hostilities, the LT-6Gs had flown more than 40,000 sorties and logged about 117,500 combat hours.

After World War II, T-6s and SNJs were supplied to NATO nations such as France, West Germany, Italy and Belgium. Latin American pilots ferried many of the trainers home after they completed their training in the United States. Lieutenant Rene Barrientos flew one of the two dozen Texans purchased by Bolivia from Kelly Field, Texas, to La Paz after completing his advanced training at Moore Field, Texas. He later became president of his country.

For use in brush-fire wars, Texans were remanufactured with rocket and bomb racks and designated FT-6Gs. They were sent to such nations as Spain, Portugal, France and Brazil for counterinsurgency missions.

The Texan was phased out of U.S. Air Force and Navy inventories in 1958, but a number of T-6s were flown by the Civil Air Patrol into the 1960s. Although the American inventory during the Vietnam War showed no T-6s, armed Texans were flown briefly by Laotian and Cambodian pilots against Viet Cong targets along the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

It is impossible to determine how many thousands of pilots have flown the Texan, but its popularity and availability on the war-surplus market after World War II resulted in many T-6s being bought and certificated to civilian standards. A Costa Rican pilot who had trained in the United States bought one, had the rear seat removed and used it to fly butter and eggs from the interior of his country to San Jose, the capital. A former Army Air Forces pilot who started an air freight service began by flying fresh flowers from Florida to New York in a T-6. Modern-day barnstormers use them for flying passengers and performing aerobatics at airshows. Western Airlines purchased three to fly mail over its routes in North and South Dakota. The movies Tora! Tora! Tora! and Black Sheep Squadron used modified T-6s to look like Japanese Zeros.

I also flew an AT-6. A bomb rack had been installed under the fuselage of this one, and I used the plane to “bomb” U.S. Geodetic Survey crews stationed at remote mountain locations in Panama with food and medicine.

A number of civilian-owned T-6s have been modified by adding more powerful engines. One, called the Bacon Super T-6S, had a tricycle landing gear, bubble canopy and wingtip fuel tanks installed in a vain effort to attract nations interested in a counterinsurgency fighter. It was featured in a movie as a Russian Yakovlev fighter.

Civilian owners of Texans have formed the T-6 Owners Association, which functions much like an antique auto-owners group, to trade parts and information. The Experimental Aircraft Association has declared the T-6 an antique aircraft. The National Air Races held annually at Reno, Nev., feature races limited to the Texans.

Nearly 400 T-6s of various models are registered as civil aircraft in the United States today. According to Larry Davis, the aircraft’s premier historian and author of T-6 Texan in Action: “It is a rare airshow in the United States that does not have at least one T-6 on display. The numbers of T-6/Harvards active in Europe have also increased over the last few years, with Texans appearing on the civil registers of England, Spain, Italy, Sweden, Switzerland, Holland, Norway and France.”

More T-6 Texans were produced than any other trainer type during World War II. No other aircraft type, not even the famous DC-3/C-47 “Gooney Bird,” has ever served in so many varied roles or has been flown by so many for so long. More than 60 years have passed since the first flight of the NA-16 in 1935, but it is a safe bet that some of its progeny will be flying well into the next century, and a few may even be flying on their 100th birthdays.

The late C.V. Glines was an award-winning aviation writer.

This feature originally appeared in the July 1998 issue of Aviation History. Subscribe here!