In Forty Autumns: A Family’s Story of Courage and Survival on Both Sides of the Berlin Wall author Willner introduces readers to her German-born parents and their families and relates the lives they led during World War II and over the following tumultuous decades of the Cold War. At the core of the book—a sweeping tale of courage, resilience and hope—are stirring accounts of her father’s escape from Auschwitz and her mother’s flight from East Germany. The narrative also details how family members who remained under the oppressive heel of Soviet totalitarianism lived their lives behind the Iron Curtain, and how as a young U.S. Army intelligence officer Willner herself pierced that curtain during covert missions in East Berlin. Military History recently spoke with Willner about Forty Autumns, her intelligence missions and her next literary efforts.

What prompted you to write Forty Autumns?

The short answer is I realized I had a story. After the fall of the Berlin Wall I met my relatives who had been trapped behind the Iron Curtain in East Germany for 40 years. During the Cold War, as a young U.S. Army lieutenant, I ran secret intelligence operations behind the Iron Curtain in East Berlin. I realized that my experience, combined with my mother’s escape from East Germany at age 20 and the account of what had happened to the large family she left behind, would make for a pretty interesting book.

Her father was a reluctant teacher in the communist system. One brother embraced communism, one sister rejected it. Another brother was a guard at the Berlin Wall with orders to shoot anyone trying to escape. And through it all there was my grandmother, who kept hope alive the family would be reunited. I decided to combine our personal story with the broader history of the Cold War, so in Forty Autumns I also trace the Soviet-American superpower battle for dominance in the space race, the nuclear arms race and battles around the globe that brought the world to the brink of nuclear war. And within that historical framework is this chronicle of my family—forcibly separated for four decades—and my operations in East Berlin.

How much of your parent’s story had you known?

How much of your parent’s story had you known?

Their story was part of our daily lives. My mother was the only one from her family to escape from East Germany, and my father was the only one in his family to survive the Holocaust, so as kids we’d ask why we didn’t have any cousins. We also saw the number tattooed on our father’s arm; no other fathers seemed to have a tattoo like that.

Our parents turned the absence of relatives into a positive, stressing the power and importance of family. Interestingly, unknown to us at the time, the same message was being used by my grandmother in East Germany to keep her family strong, together and able to survive with dignity in a secret police system that tried to pit family members against one another.

What was the most surprising thing you learned during your research?

There were many things.

My cousin Cordula was a member of the East German Olympic team and was training in East Berlin at the same time I was conducting intelligence-collection missions in the city. In fact, one of our primary collection targets was near the indoor bike track where Cordula was training. There we were, cousins, a mile or two away from each other—she a vaunted East German athlete and me an American spy.

I also learned how the East German people rose up against their own authoritarian regime in 1953, and how their uprising was crushed by the Soviets. The East Germans were the first to revolt—before the Hungarians, Czechs and Poles—and they paid a heavy price, with hundreds, perhaps thousands, killed. I also learned about the little ways East Germans coped, like secretly tuning in to watch West German TV on a regular basis. The show Dallas was a particular favorite and, at least in my family, they thought all Americans wore diamonds and furs and were driven around in limos.

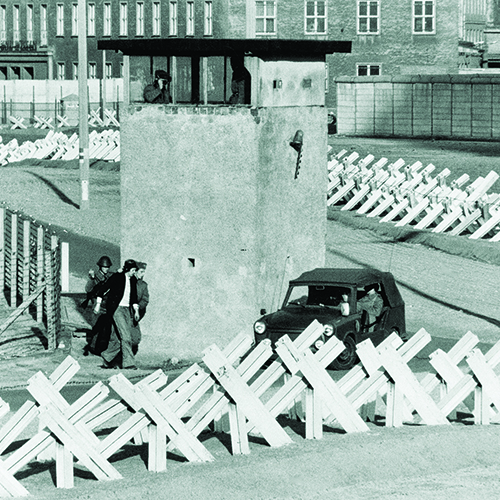

In terms of archival research, I discovered that the files of the Stasi—the East German intelligence service—contained photos of my actual intelligence operations in East Berlin. Several of those photos are in the book, along with other pictures, maps and a historical chronology.

‘We came together, united as a nation, and with our allies jointly fought a powerful authoritarian system that persecuted millions of people, and we won. We defeated communism and liberated those people’

How did your family react to the book?

In many ways it was a joint project, with much input and perspective provided by various family members. I think they wanted the story told, and as long as they felt it was accurate, they supported me. In some ways they were my toughest critics. Honestly, the most important feedback I’ve received is from my own relatives, who said I really nailed it.

Did your parents’ experiences influence your decision to enter the Army?

You bet. I became an Army intelligence officer like my father. We were both good at languages and had an interest in intelligence, and of course it was the height of the Cold War, and the Soviets were our enemies.

But there was also more to it.

After escaping from a death march in the waning days of World War II, my father was rescued by a 3rd Armored Division column. That unit contained some amazing Americans who looked after my father like a little brother until he returned to health. The soldiers became his surrogate family, and my father made up his mind that someday he would get to America and join the U.S. Army, and eventually he did. He joined in part to repay America for saving him, and he had always stressed to his children to serve our country and pay it forward.

What drew you to intelligence work?

I just found intelligence interesting and intriguing. It was the height of the Cold War, and I was not only branched intelligence, but also was assigned to Berlin—known at the time as the “spy capital of the world.” It was a great place for a junior officer to be.

What can you share about your work in East Berlin?

I was in a special unit authorized under treaty to enter East Berlin. That gave us unparalleled, up-close access to monitor and photograph anything that would help the Allies understand the threat posed by Soviet and East German forces. It was a critical mission, since at that time the most concentrated armored force in the world was on East German soil ready to strike NATO in West Germany, and NATO had to be ready if Moscow launched an attack. We reported on new weapons, we monitored rail line movements of equipment, troop training and some more sensitive things as well—really anything that would help Washington gain a better understanding of the Soviet threat.

These were almost daily missions. We entered East Berlin through Checkpoint Charlie and were immediately tailed by the Volkspolizei, Stasi or KGB surveillance teams that always lay in wait for us. After a bit of a cat and mouse chase, we’d shake them—our American Fords far outpaced their East German Trabants and Wartburgs and even the Soviet-built Zhiguli—and we’d continue on the day’s mission. There were definite risks involved, including detentions and deliberate rammings to try to scare us off. I share a few of those stories in Forty Autumns as well, including a rather intense moment when a Soviet lieutenant held a loaded gun to my head.

Did your intelligence activities help you better portray your family history?

Definitely. I directly observed how East Germans lived. I saw their lack of freedom—probably somewhat like North Korea today—the grayness, lines for food and for substandard household products that might not be available when you got to the head of the line. East Germans lived in a bubble, distant and reclusive even from one another, and had been conditioned to fear foreigners. They lived under the eyes of a pervasive secret police force, with neighbor spying on neighbor. The regime censored everything—textbooks, newspapers, the broadcast media—and even controlled their citizens’ thoughts and imprisoned anyone who challenged them. In the course of our missions, though, we also met people out of earshot of the Stasi who told us they were happy we were there, did not believe the East German regime’s propaganda, and hoped and prayed for the fall of the Berlin Wall. My family members had many of these same experiences, so I feel fortunate to have been able to see all that firsthand.

Do you feel the Cold War is still influencing current events?

Let me tell you, there is nothing about authoritarianism that can be taken lightly. Countries like Vladimir Putin’s Russia do not wish us well. I see things there slipping backward—the killing of dissidents, gaslighting, wet operations and so on—and that worries me.

Also, I think it’s important to remember that we stood up to that threat during the Cold War. We came together, united as a nation, and with our allies jointly fought a powerful authoritarian system that persecuted millions of people, and we won. We defeated communism and liberated those people. Millions of people participated in the struggle to end the Cold War, and some lost their lives in incidents around the world. In East Germany, for example, my colleague Maj. Arthur Nicholson was shot and killed by a Soviet sentry while conducting a mission to further that aim in East Germany. Those sacrifices should never be forgotten.

What drew you to a career in human rights advocacy?

If you are against totalitarian communism, promoting human rights is a natural outgrowth. I’ve worked for U.S. government and for nongovernmental organizations around the world, including in Eastern Europe, Russia, Belarus and the Czech Republic, to promote democratic principles, the rule of law and to educate others about how we can move society forward.

Tell us about your next book.

I’m writing the story of that brave company of 3rd Armored Division soldiers that saved my father. I got a chance to know many of them, and they became like uncles. Their journey—from D-Day through the Battle of the Bulge to the capture of Cologne—is epic. And as I chronicle their story, in sort of a parallel telling, I also take you through what my father and his buddy, another Jewish teenager, experienced while fighting to survive slave labor in Auschwitz and Buchenwald. So you really have two incredible accounts which you follow simultaneously and which eventually merge together—and ends with the Americans and our Allies saving the day.

It’s really a story of the American spirit, and of heroism and sacrifice. The war was a costly and brutal endeavor, and those who survived bonded forever. The guys I write about in the new book would meet every year to stay connected and lean on each other. One of those reunions, by the way, was hosted by my father at our house in Falls Church, Va. They were great and humble men from every walk of life and every corner of America who truly came together as one to fight a better equipped and brutal enemy, and they defeated the Nazi regime. I’m proud to be able to tell their story. MH

This article was published in the July 2020 issue of Military History.