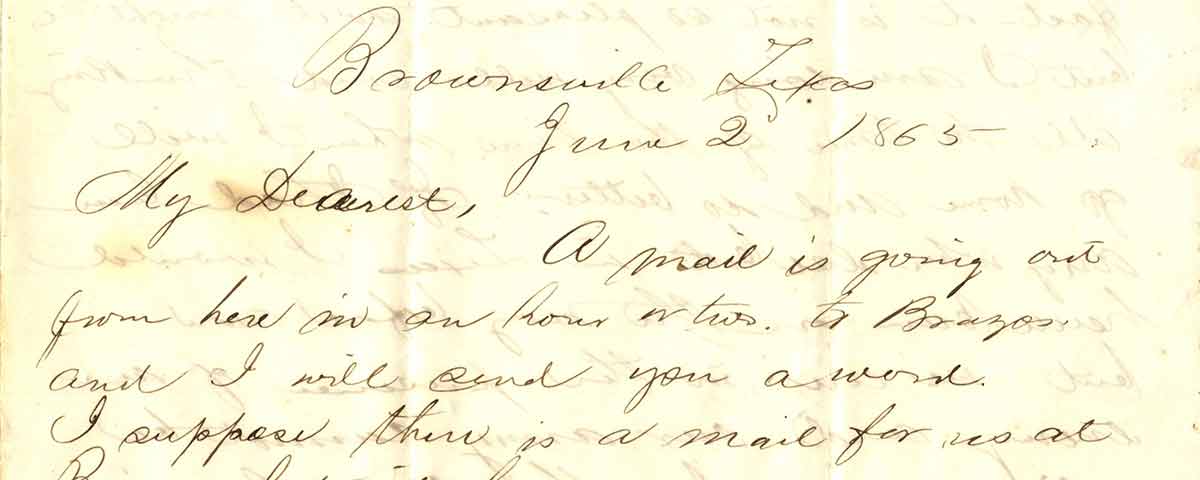

www.bluetigercommons.lincolnu.edu/foster—letters/

In the spring of 1865, about a month before the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia, Union Lieutenant Richard Baxter Foster waged a very different war in the Trans-Mississippi West. Baxter was, he explained in a March 8 letter to his wife, Lucy, “teaching a school of the Sergeants and Corporals of the Company about one hour each day.” It was a task in which he took “great pleasure,” enjoying the fact that the “men are very much interested and thank me every night for the lesson. I never saw a body of men so anxious to learn as our regiment now are.”

A native of New Hampshire and graduate of Dartmouth College, Baxter had moved to Illinois and then Iowa in the 1850s, where he was teaching African-American students and fighting in Kansas alongside John Brown until Baxter moved to Nebraska shortly before the Civil War began. He enlisted in the 1st Nebraska Infantry in 1862, and then volunteered to command an African-American unit the following year. His letters and his military service highlight the fact that Baxter fought to abolish slavery.

Lincoln University, of Jefferson City, Mo., which Baxter helped found as Lincoln Institute in 1866 with the support of the men of the 62nd and 65th USCT, has posted online several of his letters that span his time with the 62nd USCT from 1863-1865. The collection is not vast and it relates to a unit that saw little fighting. But the value in Baxter’s correspondence lies in the number of issues he addresses. Many readers, for example, associate abolitionist-minded Union soldiers with those who served in Eastern units, and generally consider Western units to be unsupportive of emancipation. Baxter challenges this assumption, and while he expresses the common complaints of soldiers including long-overdue pay, poor commanders, and too-few letters from home, he also fumes about policies that Baxter thought caused more harm than good in the Trans-Mississippi West.

The greatest value of the collection, though, is Baxter’s reflections on the role African Americans played in the war and would play in the peace that followed. He observed in late May 1865 that while white officers were rapidly resigning from service in the summer of 1865, black soldiers remained. Recognizing the possible limits of emancipation, he noted on May 24 that “the white troops would want to go home [but] the black men don’t, they would rather stay in the army awhile than take their chances any where else for which they are sensible.” Baxter also expressed his desire to establish a new community after the war with men from his company, a trend among veterans that scholars are studying with increasing interest in the Trans-Mississippi West.

Baxter proved pivotal in the 62nd USCT’s tireless efforts to open a school to educate African Americans after the war. While the online collection does not include letters on that phase of his work, they highlight a key part of the process where Baxter had the opportunity to work closely with free blacks and former slaves-turned-soldiers who recognized that education would be key to enjoying freedoms the war secured. —Susannah J. Ural