Borne out of desperation—and perhaps a touch of ingeniousness—the Imperial Japanese Army in November 1944 began unleashing an estimated 9,300 “fire balloons” across the Pacific Ocean.

It was thought that only 10 percent of these fusen bakudan would complete the journey. But the Japanese hoped that the balloons that did land would destroy buildings, set fires, and incite fear among the American civilian population in this random campaign of terror.

Thanks to the American ethos of “loose lips sink ships,” it didn’t work.

The “Great Balloon Bomb Invasion,” a 1 hour 37 minute documentary now streaming on Discovery+, explores the history of the balloon bomb—known to the Imperial Army by its code name, Fu-Go.

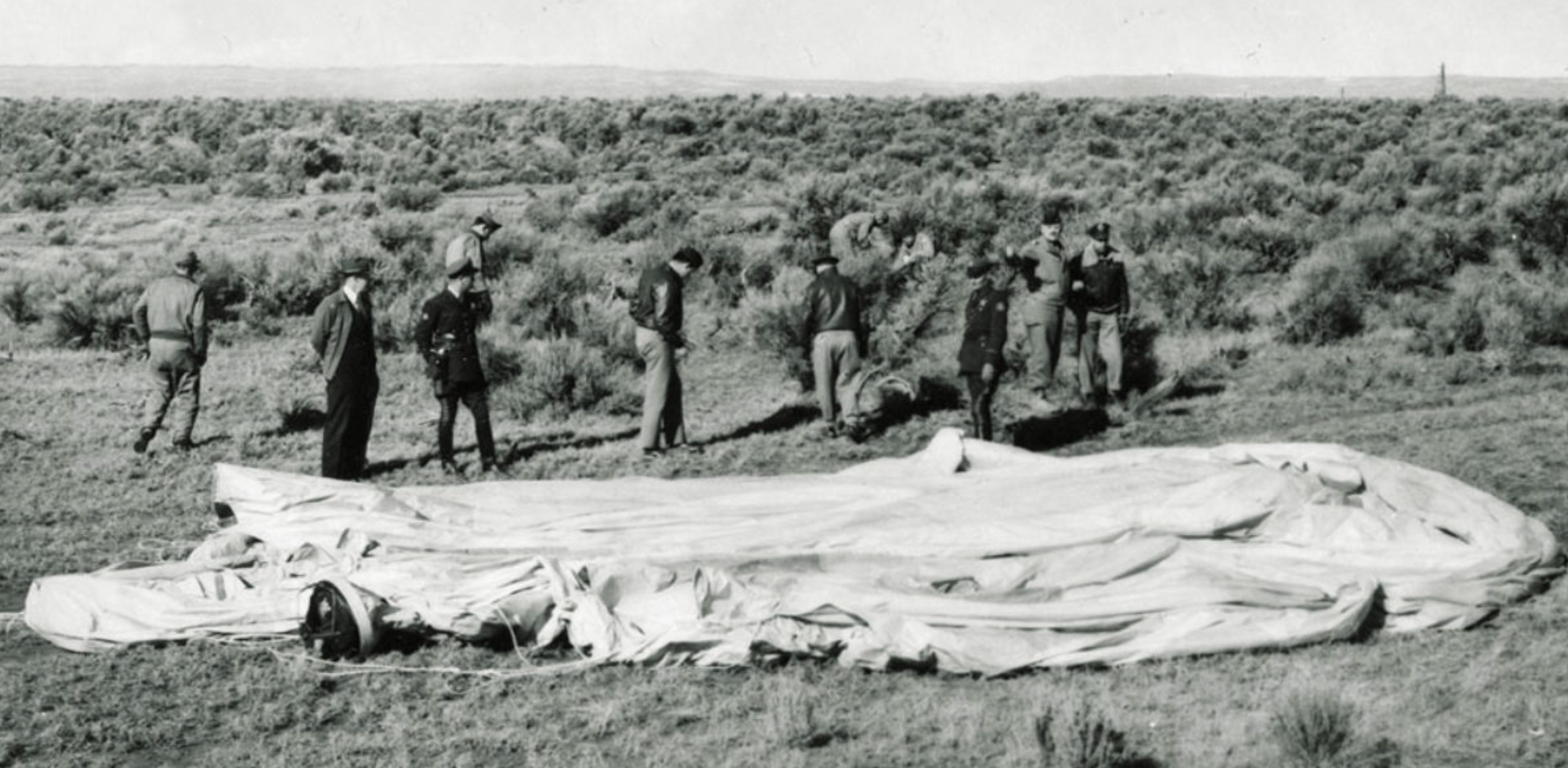

Although it’s estimated about 1,000 Fu-Go bombs reached North America, only about 300 balloons were ever documented.

“Potentially thousands of deadly bombs scattered across the U.S.,” the makers of “The Great Balloon Bomb Invasion” say in a news release. And for the first time in more than 75 years, historian and author Martin Morgan led “an investigation … into the hidden history of this attack, with a high-tech hunt for the unexploded remnants.”

The documentary features expert interviews and eyewitness accounts, as well as never-before-seen archival footage, as the story of the Fu-Go bombs unfolds from past to present tense.

The weapon itself was “a huge balloon made of four layers of impermeable mulberry paper,” writes author Daniel B. Moskowitz. “Each measured 33 feet in diameter, was inflated with 19,000 cubic feet of hydrogen, and carried ordnance—usually a 26-pound incendiary or 33-pound high-explosive bomb, along with four 11-pound incendiaries.”

The Japanese released the unique weapons up and out through the jet stream, equipping the Fu-Go bombs with devices to vent hydrogen when they rose above the jet stream and jettison ballast when they fell below it. Those that had successfully traveled the 6,200 miles across the ocean would eventually start releasing their bombs.

As the balloons began to fall on North American soil, they were largely met by a curious public, not a panicked one.

According to Moskowitz, the U.S. government’s public information response went through three distinct stages, which shifted along with knowledge of the attempted attacks. Phase I of the public response was to admit that uncertainty. Only after it became clear that these were Japanese weapons did Phase II begin, with the government trying to contain public knowledge of the devices. But after six people were killed in an encounter with a balloon-borne bomb near Bly, Oregon, the government’s public information policy changed again; in Phase III, authorities warned citizens of the dangers of the devices.

By April 1945, unbeknownst to government officials, the Japanese had abandoned the effort, not knowing the extent of damage they had caused. Yet scores of balloons strapped to their dangerous incendiaries remained—and still remain—off the beaten paths across the U.S.

While the viewer follows Morgan and his hunt for these potentially deadly Fu-Go bombs, it is the largely unexplored history behind these attacks that holds the viewer’s attention.

From interviews with Japanese women—just schoolchildren at the time—who helped sew the balloons for the Imperial Japanese Army to the story of the all-Black airborne unit—the 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion, nicknamed the Triple Nickles—who fought the Fu-Go fires along the Pacific Coast, the “Great Balloon Bomb Invasion” charts the ingenious yet ultimately ineffective Japanese terror campaign.

As a May 29, 1947, New York Times story put it: “Japan was kept in the dark about the fate of the fantastic balloon bombs because Americans proved during the war they could keep their mouths shut. To their silence is credited the failure of the enemy’s campaign.”