Waves of C-47 Skytrains in formation flew east across the English Channel toward Normandy under cover of darkness, an overcast sky eclipsing the stars and moon above. In one plane a stick of 16 paratroopers from Company I of the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment (506th PIR), 101st Airborne Division, sat silent, each man lost in thought. Their mission was clear enough: From their drop zone they were to move south, seize two footbridges at the mouth of the Douve River and expand them into a bridgehead.

Over the Cotentin Peninsula a dense fog enveloped the landscape, providing additional cover but sending the formation into disarray. As the fog cleared, the planes began to take heavy anti-aircraft fire. Hit by flak, a few of the C-47s lurched and plummeted to the ground, one in flames. As Company I’s plane fishtailed across the sky, it dropped from 700 feet down to 400 feet, shuddering as it descended.

The jumpmaster began to bark out commands:

“Stand up!…Hook up!…Sound off for equipment check!”

When he opened the door, the wind noise and engine roar required him to holler even louder. “Stand in the door!” A moment passed before he tripped the green light. “Go!”

Technical Sergeant Joseph Beyrle grabbed the doorframe for balance before throwing himself into chaos. As his chute opened, tracer rounds crisscrossed the sky around him, some striking his fellow troopers. Within 30 seconds of leaping from the plane, Beyrle found himself drifting down toward a church, bursts of gunfire issuing from its steeple. Landing with a thud on the roof, he tumbled down its steep grade and dropped 15 feet to the ground. Recalling the pictures, maps and sand tables from his company’s intensive mission briefings, Beyrle realized he was in Saint-Côme-du-Mont, a half-mile from the unit’s intended drop zone and 3 miles west of the Douve River bridges.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

German troops scurried to and fro, their silhouettes in motion against a blazing house in the village. Hoping to link up with his fellow paratroopers, Beyrle headed toward their assigned objective. Over the next 20 hours he cautiously made his way east, en route carrying out the secondary objective of harassing German forces. Beyrle knocked out a power substation with explosive charges and hurled grenades at passing groups of German soldiers. While maneuvering through hedgerow country, he heard a rustle in the thickets and decided to chance making contact. Taking out his cricket—the small metallic signaling device issued to airborne soldiers—he squeezed off a single-tap click-clack to request identification.

Expecting the requisite click-clack, click-clack in reply, Beyrle instead heard a gruff German voice commanding, “Hände hoch!” (“Hands up!”)

MICHIGAN BOY

Joe Beyrle was no stranger to privation and hard work. Born in Muskegon, Mich., on Aug. 25, 1923, he was the fifth of seven siblings who came of age during the Great Depression. At the low point Beyrle’s father lost his factory job. Evicted from their house, the family moved in next door with Joe’s maternal grandmother. To help meet the family’s needs the boy swept floors for loose change, rummaged grocery store bins for discarded food and patiently stood in lines for government handouts. He became a gifted track and field athlete in high school, but when the United States declared war after the Dec. 7, 1941, Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Joe declined a scholarship to Notre Dame and instead volunteered for the Army’s new airborne forces. There was just one problem: Joe was color-blind.

At the local recruiting office Joe asked the sergeant in charge whether his color-blindness would disqualify him from the airborne, as he would be unable to differentiate between the red and green signal lights prior to a jump. The sergeant asked Joe if he’d ever gotten a traffic ticket for running a red light.

“No,” Beyrle replied.

“Then don’t worry,” said the sergeant, “A dozen guys will push you out when the light changes.” With an approval stamp on his application, Beyrle was accepted into the U.S. Army.

After his induction at Fort Custer, Mich., Beyrle was sent to Camp Toccoa, Ga. There he was assigned to the 506th PIR, whose motto, “Currahee,” is the Cherokee word for “stand alone.” After basic training Joe specialized in radio communications and demolition and was eventually promoted to technical sergeant.

On Sept. 17, 1943, a year to the day Beyrle had enlisted in the Army, the 506th PIR arrived in Britain and hopped a train for Ramsbury, England, just west of London. For the next nine months the men trained hard for the anticipated Allied invasion of Nazi-occupied Europe. American paratroopers conducted combat exercises in the countryside, while Allied ground troops practiced amphibious landings along the coast. Meanwhile, behind closed doors military planners worked out the details of Operation Overlord.

In April 1944 Beyrle was one of three 506th PIR volunteers selected for a covert airborne mission into Nazi-occupied Normandy to deliver bandoliers filled with gold coins to the French Resistance. In the dead of night the trio dropped into a field near the town of Alençon, where they connected with Resistance fighters before being smuggled back to Britain. In early May they repeated the feat. A month later, on June 6, Beyrle would again parachute into France, though this time there would be no speedy return to Ramsbury.

CAPTURED!

After his capture by German troops Beyrle joined other POWs in a column marching south toward the enemy garrison at Carentan, en route coming under artillery fire from advancing American units. During the barrage Beyrle was struck in the left buttock by shrapnel and blown into a nearby ditch. Recovering from the shock, he helped bandage and apply tourniquets to a pair of fellow GIs whose legs had been blown off. Amid the confusion, Beyrle and two other POWs melted into the roadside brush and ran for it. Losing his captors and fellow fugitives in the hedgerows, Beyrle wandered aimlessly for hours until recaptured.

The Germans loaded Beyrle and other American POWs into trucks and sent them farther inland to Saint-Lô. That column, too, came under attack—strafed by U.S. aircraft. Fortunately there were no further casualties. Later that night Allied bombers turned most of Saint-Lô into rubble, killing scores of Germans and French civilians, though not one bomb struck the stable in which the prisoners were held. The next morning the POWs were marched south to the village of Tessy-sur-Vire, outside of which was a walled monastery the Germans had turned into a holding pen. The prisoners soon dubbed it “Starvation Hill.”

Bounced to yet another compound, Beyrle and fellow POWs endured austere conditions as the Germans put them to work rebuilding the rail lines that had come under continual Allied bombardment. Next moved to a warehouse near Paris, the men sat idle for two weeks with little food and water. After a humiliating march through the streets of the French capital, during which onlookers spat on and pelted Beyrle and the others with food, the Germans loaded the POWs onto an eastbound train, its boxcars overcrowded and lacking sanitary facilities. During the journey Allied fighter planes strafed the train, killing several prisoners and wounding some two dozen others on Beyrle’s boxcar alone. But the train didn’t stop. The POWs remained locked inside for five more days before reaching their destination.

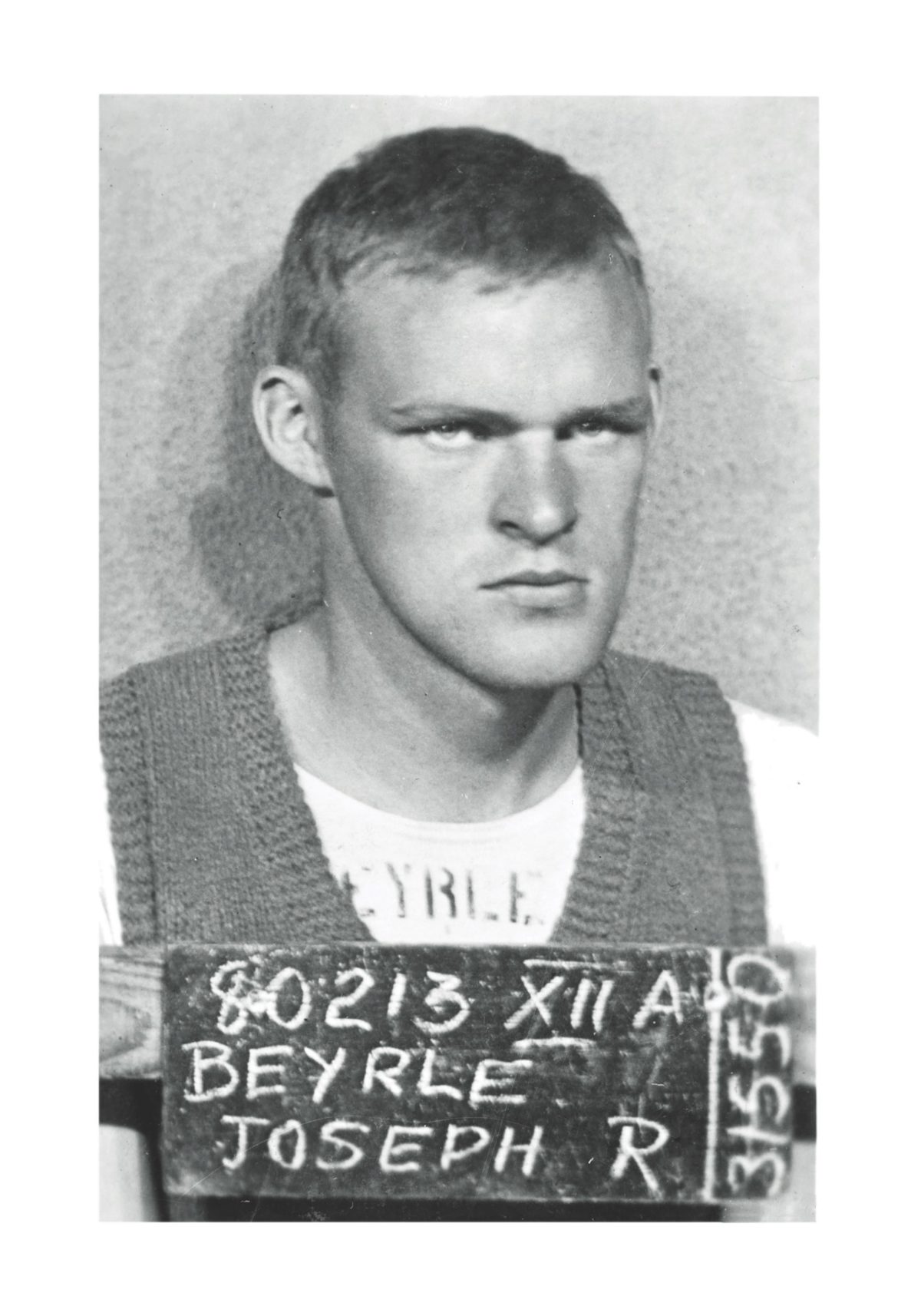

When the train finally rolled to a stop and the boxcar doors opened, the prisoners found themselves at Stalag XII-A in Limburg, Germany. There Beyrle and the others were formally registered as POWs, then given numbers, a shower, a shave and a chance to write home to their families. A week later the Germans loaded the prisoners on another train, bound for a camp south of Berlin. Finally, on Sept. 17, 1944, Beyrle arrived at Stalag III-C in Alt-Drewitz, Germany (present-day Drzewice, Poland), 50 miles due east of Berlin.

Among the most precious commodities in the POW camps were cigarettes, which served as a form of currency and as bargaining chips. Soon after arriving at Stalag III-C, Beyrle won 60 packs of cigarettes in a dice game, and he and two fellow prisoners decided to bribe a guard with the coveted smokes in exchange for an opportunity to escape.

Having worked out a deal with the guard, Beyrle and his companions—whom he later recalled only as Brewer and Quinn—cut through the perimeter wire and made their way to a rail yard just south of the camp. According to an informant, each night a train would pass through bound east for Poland, where the trio hoped to connect with either the Polish Resistance or advancing Russian troops. They managed to sneak onto the designated train, but when it stopped a few hours later, Beyrle and companions were horrified to find themselves in Berlin, the capital of Nazi Germany.

GERMAN UNDERGROUND

Beyrle, Brewer and Quinn had no option but to remain hidden in the freight car the entire day. That night, while making their way across the darkened rail yard, the men encountered an elderly German worker. Explaining their predicament, Joe offered the man several packs of cigarettes in exchange for his help. The German agreed, then continued on his rounds. Later the next day he returned with bread, sausage and beer, and at nightfall he hid the fugitives in his wagon and took them to meet with members of the German underground, who promised to help the trio return to Allied lines. Meanwhile, they concealed the fugitives in the basement of a safe house.

The next morning the escapees woke to the sounds of gunshots and raised voices from upstairs. The Gestapo had gotten wind of the safe house, and its agents soon found the Americans in hiding. Beyrle later recalled the aftermath:

In the next seven to 10 days we found out everything we had heard about the Gestapo was true. We were interrogated, tortured, kicked, knocked around, walked on, hung up by our arms backward, hit with whips, clubs and rifle butts. When you thought they could do no more, they would think of other ways to torture you. When you would slip into semiconsciousness, they would start again. This went on for days at a time, and then they would dump you into a cold, dark cell with no sanitary facilities and dirty from a previous occupant.

Days into the brutal interrogation session a group of Wehrmacht officers arrived at Gestapo headquarters to reclaim the escaped POWs, asserting the trio remained under military jurisdiction. Spared further torment by the Gestapo, the fugitives were returned to Stalag III-C. As punishment for their escape each man was sentenced to 30 days of solitary confinement in a 6-by-4-foot cage with meager rations of black bread and water. As temperatures were dropping sharply with the onset of winter, death by freezing was a real possibility. A week later all three were released from solitary when visiting members of the Red Cross intervened on their behalf.

By January 1945 Beyrle was once again contemplating escape. From radios they had secreted in their barracks the POWs learned Soviet troops were rapidly advancing through Poland, and Beyrle believed their best hope for freedom was to connect with the advancing Russians. After much discussion he, Brewer and Quinn hatched an audacious escape plan. While in the exercise yard one would fake a seizure, and the other two would run for a stretcher. All three would then ostensibly head to the dispensary while POWs in the yard started a fight to distract the guards.

The attempt began auspiciously enough, the Germans becoming preoccupied by the commotion in the yard. Carrying Quinn on the stretcher, Beyrle and Brewer made it past the gate and headed toward the dispensary. Once out of sight of the guards, they hid inside empty barrels on an outbound supply wagon. Just outside camp, however, the wagon tipped over after hitting a large stone, and the three stowaways tumbled from the barrels. As the trio ran for cover, the guards opened fire, gunning down Brewer and Quinn. Then they unleashed their dogs. Thinking fast, Beyrle jumped into a nearby stream, where the dogs lost his scent. Having escaped from captivity a third time, he headed east, resolving to reach Russian lines.

For the next three days Beyrle picked his way through German territory, the sounds of artillery and gunfire intensifying as he neared the front. During a period of particularly heavy fighting between German and Soviet troops he hid in the hayloft of a barn. After a while he heard the rumble of approaching tanks, soon accompanied by Russian voices. Clambering down from his hiding place, Beyrle emerged from the barn with hands high and walked slowly toward wary members of what turned out to be the Soviet 1st Guards Tank Army. Holding up a pack of Lucky Strike cigarettes and smiling broadly, the American fugitive shouted out the only Russian phrase he’d memorized: “Amerikanskiy tovarishch!” (“American comrade!”).

MAJOR RUSSIAN

After a few tense moments the Soviets lowered their weapons and brought Beyrle before their commanding officer.

The American was shocked to find the Russian commander was an attractive young woman. Known to him only as “Major,” she was likely Aleksandra Samusenko, a legendary tank commander who had received the coveted Order of the Red Star for taking out three German Tiger Tanks during the 1943 Battle of Kursk. Beyrle recalled their meeting:

I told her that I was an escaped U.S. POW, and I wanted to join them and go to Berlin with them and kill Nazis. After much consultation between the commander and the Soviet commissar, I was allowed to join them and was given a Russian submachine gun with a round drum.

Fighting their way into eastern Germany, the 1st Guards Tank Army ultimately found itself in the vicinity of Stalag III-C, Beyrle’s onetime POW camp. Along the way the Russians encountered a group of American prisoners marching east from the camp under German guard. Sadly, several of the POWs were killed during the subsequent firefight with the enemy. The next day, January 31, Beyrle and the Russians stormed Stalag III-C, overwhelming the guards and freeing thousands of Allied prisoners.

After liberating the camp, Beyrle continued west with his Russian comrades, determined to reach Berlin. For the next two weeks he fought as a member of the 1st Guards Tank Army, witnessing some of the most brutal fighting of the campaign. Soviet troops were advancing in overwhelming strength and numbers, but resistance was intense as German forces fought desperately to defend the fatherland.

Early one morning the American sergeant was riding in the westbound Soviet column of U.S.-made Sherman tanks, just a few miles from Berlin, when a group of German Stuka dive-bombers swooped in from the rear. During the surprise attack Beyrle was badly wounded in the right leg and slipped in and out of consciousness as a Russian medic helped him to the rear. He was among dozens of wounded men evacuated to a Soviet field hospital in Landsberg an der Warthe, Germany (present-day Gorzów Wielkopolski, Poland).

As Beyrle recovered, the hospital was honored with a surprise visitor—Marshal Georgy Zhukov, the Soviet Union’s most decorated military commander. Zhukov was a veteran of World War I, the Russian Civil War and the undeclared Soviet-Japanese border war. During World War II he played a leading role in numerous campaigns and was one of only two men (the other being Leonid Brezhnev) awarded the title Hero of the Soviet Union four times. As Zhukov greeted the hospitalized troops, he was astonished to find an American. Through an interpreter Beyrle explained who he was, where he came from and how he wound up fighting with the Red Army. His story fascinated the Russian general, who promised to help him get home.

The next day Beyrle was told he would be transported to Moscow. With Zhukov’s letter of introduction in hand, he made his way by truck convoy and hospital train to the outskirts of the Soviet capital. A senior Russian officer then escorted Beyrle to the U.S. Embassy just off Red Square, where he was promptly fed, doctored and given a clean uniform. The young American’s excitement turned to disbelief, however, when he was spirited away to a nearby hotel for questioning by a pair of U.S. Army officers as an armed Marine sergeant looked on. When Beyrle asked why he was being interrogated, the men explained that, according to their records, Joseph R. Beyrle had been killed in action in France on June 10, 1944.

Beyrle’s Legacy

When Beyrle was captured on D-Day, a German soldier had taken his dog tags. Days later U.S. troops discovered the tags on an unidentified body in the Normandy countryside. Believing the corpse to be that of Beyrle, the Army had recorded his death and sent a telegram to his parents in Muskegon, informing them he’d been killed in action. The Catholic family had held a funeral Mass, and Joe’s name was duly inscribed on his hometown war memorial. Only when his parents received Joe’s postcard from Stalag XII-A in Limburg did they realize he remained alive. Apparently, though, they’d neglected to inform the Army.

A few days of questioning convinced the Army counterintelligence officers at the U.S. Embassy of Beyrle’s identity, and he was eventually transported from Moscow to Naples, Italy, where he underwent surgery to remove the shrapnel from his wounds. On April 1 Beyrle shipped out for the 10-day voyage home. After three months of leave with his family in Michigan and four months of further rehabilitation at a military hospital in Florida, he was honorably discharged that November.

After the war Beyrle married (the ceremony performed by the very priest who’d presided over his “funeral”) and raised a family. During a 1994 White House ceremony Russian President Boris Yeltsin presented the American former paratrooper with four decorations in recognition of his wartime service with Soviet forces. On Dec. 12, 2004, the 81-year-old veteran of two armies died peacefully in his sleep while visiting Toccoa, Ga., where six decades earlier he had trained as a paratrooper. He was buried with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery.

Daniel Ramos is a researcher and freelance writer on military topics who works for the National September 11 Memorial & Museum in New York. For further reading he recommends Behind Hitler’s Lines: The True Story of the Only Soldier to Fight for Both America and the Soviet Union in World War II, by Thomas H. Taylor.