William Frederick Cody and Nate Salsbury were as unlikely partners as ever trod the sawdust or sand, but Salsbury deserved a big share of the credit for Buffalo Bill’s reputation as the greatest showman of his time. Salsbury kept the books, a job Cody was unqualified to handle. Trouble is, toward the bitter end of his life, Salsbury thought he deserved all the credit.

“A man may be a ‘Great Scout’ and a d____d rascal at the same time,” Salsbury wrote from retirement in Long Branch, N.J., the American Riviera of the Gilded Age. “I invented every feature of the Wild West show that has had any drawing power.” Visiting Victorian Britain and aristocratic Rome, Cody had dropped in at the homes of dignitaries while visibly drunk, Salsbury claimed. “He could hardly get into his carriage” with a lady who was manifestly not Mrs. Cody—and nobody cared. Pope Leo XIII once spotted Cody and Salsbury seated in the Sistine Chapel—longhaired Buffalo Bill clad in his dress coat and apparently minus his “concubine,” as the married Salsbury called her. “His Holiness,” Salsbury related, “spread his hands in token of his blessing, and the good Catholics around us looked with envy at Cody during the balance of the ceremonies.”

Salsbury noted that Cody imitators were popping up like mushrooms at the turn of the 20th century, and if any of them “had had the good fortune to be good looking, tall, dashing and the subject of romantic tale telling for a decade, there would have been some other commercial propositions that could have been developed.” Salsbury, a Civil War veteran, was also unimpressed with the harumscarum exploits that made Cody a dime novel hero: “I smelled more powder in one afternoon at Chickamauga than all the ‘Great Scouts’ that America has ever produced did in a lifetime,” he wrote. When Cody’s sister Helen penned her adoring biography Last of the Great Scouts, Salsbury wrote archly, “If she will only ensure the verity of her title page, she will be doing humanity a service.”

Salsbury’s family had deep roots in New England, but he was born in Rockport, Ill., in 1846. At 15 he entered Civil War service (as one of the youngest soldiers, not counting drummer boys, in the Union Army) with the 15th Illinois Volunteer Infantry Regiment.Wounded and discharged, he recovered to serve with the 89th Illinois at the Battles of Chickamauga and Chattanooga and later with the 59th Illinois in Texas. He was good with a musket and with his vocal cords, his singing providing spontaneous campfire entertainment. Salsbury also was enterprising. His buddies liked to play cards, but many didn’t play well. He left the Union Army at war’s end with $20,000.

Ironically, while studying banking and finance at an Illinois business college, Salsbury ran out of money. To earn cash, he tried out for a theater role in Grand Rapids, Mich., landing the part of Colorgog in the play Pocahontas. The manager offered Salsbury $12 a week but warned him he’d be lucky to collect it. Indeed, the play closed on the first night. But Salsbury, to the horror of his family, was hooked on showbiz.

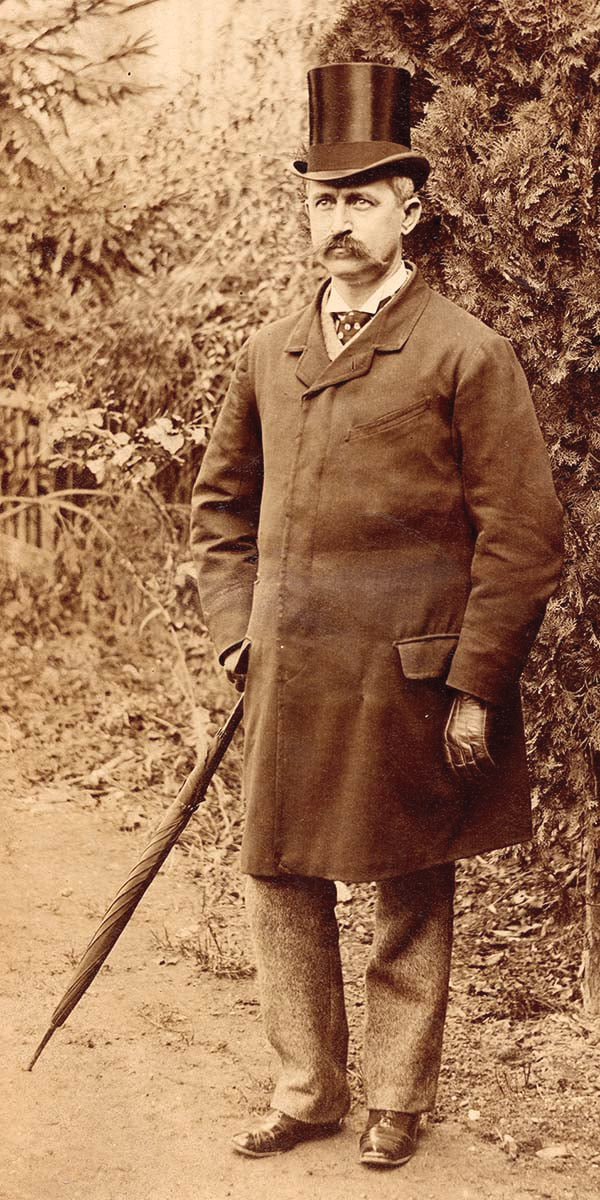

Incongruous as it seems, given his stiff demeanor in later years, Salsbury spent four years onstage at the Boston Museum as a comedian. He and John Webster formed a stock company called the Salsbury Troubadours and toured the United States and Europe in the 1870s. In 1879 Salsbury wrote and performed in The Brook; or, A Jolly Day at the Picnic, a vehicle for songs, dances and comedy turns among friends in what some have called the first American musical comedy. While The Brook was a hit, it couldn’t compare to the thrill of a staged stagecoach robbery, a buffalo stampede, a scaled-down simulation of Custer’s Last Stand or an encounter with Sitting Bull, waving and signing autographs. In late 1883, with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West in financial trouble, Salsbury latched onto the legend with a $5,000 loan.

While Cody had continual trouble keeping ahead of his creditors, Salsbury had an almost jugular instinct for finding operating cash. For the next two decades, Salsbury, as the nominal “owner” due to Cody’s credit profile, ran the Wild West in terms of finances and logistics, while Cody was the figurehead, a rip-roaring crowd-pleaser, drunk or sober.

Salsbury claimed—and some experts agree—he was the one who hired Annie Oakley, the show’s greatest single star other than Cody himself. The lesser known partner routinely rounded up food and fodder for 600 cowboys and Indians and 1,000 horses and tamed bison. He also handled bookings and payrolls. Cash flow was a challenge. Cowboys earned from $50 a month up to $120 for exceptionally skilled ropers and trick riders. Indian“warriors” (some the real thing) got $25, “chiefs” $30–$60, and translators up to $125. Cody and Salsbury also provided $10 for each wife and $5 for each little Indian who camped in a tepee as spectators filed by to gawk at them. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West was the biggest employer Pine Ridge Reservation had in the 1880s and 1890s. Cody paid better than the reservation’s Indian police ($10 a month) or leading freight wagon companies. Cody’s Wild West Lakotas, eager tourists, were respectful to the pope, but they couldn’t stop laughing when they saw the colorful uniforms and“gigantic tomahawks” of the Swiss Guard. They thought someone was pulling their leggings.

Salsbury was, above all, a logistical genius. Annie Oakley recalled that when the Wild West reached Germany, in 1891, at least 40 officers from the elite Prussian Guard stood around taking notes on how long it took Cody’s crews to unload railroad cars, pitch tents and construct simulated forts and saloons. Salsbury encountered a personal logistical problem in 1892. His wife Rachel, a U.S. citizen of Polish and German ancestry, had already given birth to Nathan Jr. in 1888 and Milton in 1890. In February 1892, she gave birth to twin girls in Glasgow, Scotland, while Salsbury himself was on a quick fund-raising trip back to the United States. The cowboys and Indians were delighted until someone told them that if the babies weren’t registered with the American consul within three days, they’d go on the books as British rather than American citizens. Major John M. Burke, Cody’s “general manager” (actually, press agent), hopped a fast train to London but hadn’t been told what names to give the girls, so they were recorded as Rachel Jr. and Rebecca. Salsbury returned to England with the greenbacks, and 6 million people saw Buffalo Bill’s Wild West in 1893.

What soured relations between Cody and Salsbury, other than a clash of egos, isn’t clear, but in 1895, Salsbury, proud Union veteran of the Civil War, talked Cody into offering “Black America,” a show that depicted the horrors of the auction block and the whipping post along with black cowboys, blacks in Union blue and buffalo soldiers. The show bombed in Brooklyn, and bankruptcy loomed. Salsbury staved off creditors by brokering a partnership deal with James Bailey of Barnum & Bailey Circus fame. Between 1897 and 1899, Cody and Salsbury tried —and failed—to irrigate nearly 25,000 acres of land in northwestern Wyoming with water diverted via canals from the Shoshone River. In October 1901, a catastrophic train wreck killed about 100 of the show’s horses and injured a number of performers, including“Little Sure Shot” Annie Oakley, Cody’s remaining star, who slipped into retirement as gracefully as possible. Cody himself—minus the ailing Salsbury and by now wearing glasses and a wig—couldn’t afford to retire. His free-spending ways and poor investments had left him on the verge of bankruptcy. Buffalo Bill finished his career as an employee earning $100 a day.

Salsbury died an unrepentant Scrooge on Christmas Eve 1902, the president of the Long Branch Property Holders’ Association, recent builder of a $200,000 development of handsome cottages known—possibly for old times’ sake— as The Reservation and a solvent and respected citizen of Elberon, a suburb of affluent Long Branch. He left behind his wife, four children and three servants. Two years earlier, Buffalo Bill, in a sense, had offered a caustic obituary for his own fiscal blunders and for his gifted but envious alter ego: “When you die it will be said of you, ‘Here lies Nate Salsbury, who made a million dollars in the show business and kept it,’ but when I die, people will say, ‘Here lies Bill Cody, who made a million dollars in the show business and distributed it among his friends.’”

Suzie Koster and Minjae Kim assisted John Koster with research on this story.

Originally published in the December 2010 issue of Wild West. To subscribe, click here.