Among failed North American colonies, Roanoke, on the mid-Atlantic coast, is the most famous, thanks to legend and tourist attractions near where that storied venture took place. Other unsuccessful North American colonies get little attention beyond occasional, often cryptic references in the literature. Yet

By David MacDonald and Raine Waters

1526-1689, Westholme, 2020, $30

each colony that failed has much to reveal about the challenges early European arrivals encountered, about the native peoples forced to interact with those interlopers, and about human nature. All colonies, successful and unsuccessful, faced similar challenges, as illustrated in the following sketches based on our book, We Could Perceive No Sign of Them: Failed Colonies in North America, 1526-1689 (Westholme, 2020; $30).

San Miguel de Gualdape

In September 1526, Spanish official Lucas Vasquez de Ayllón founded San Miguel de Gualdape, the earliest colony in what is now the United States. In landing on the southern Atlantic coast, Ayllón was following a path taken by Juan Ponce de León, who in 1521 had attempted to establish a colony on the peninsula the Spanish called Florida. Native Indians previously targeted by slave raiders drove off the settlers before they could accomplish anything; Ponce de León, struck by a poisoned arrow, died.

Starting with Christopher Columbus’s arrival in the Caribbean in 1492, Spain established colonies in the Caribbean, Mexico, and South America. Ayllón set forth in July 1526 from the northern coast of Santo Domingo, Spain’s colony on Hispaniola, with about 500 men ranging from nobles to farmers, along with an unknown number of women, children, and Black slaves. Sailing north, the party landed near Winyah Bay in what is now South Carolina. Because it was on the same latitude as Spain, they were assuming they would find a region as fertile as the one they had left behind. Instead, there was only sand and swamp. Covering 120 miles southbound in search of arable land, the travelers settled on a parcel on Sapelo Sound near the mouth of the Sapelo River; the site has never been found. The colonists had nearly exhausted their provisions. Local Guale Indians, though friendly, had no surplus food. Malaria, dysentery, typhoid, and other illnesses compounded the colonists’ hunger. Ayllón and many other colonists fell sick and died. One group of survivors left to exploit Indians in a nearby village. Others argued over whether to evacuate to Santo Domingo or to wait for resupply. The slaves revolted and, allying with the now-alienated Indians, attacked the whites. After only three months in Florida, the remaining colonists abandoned San Miguel. Many died during the voyage to various Spanish ports in the Caribbean; about 150 survived. Historian Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés, a friend of Ayllón, blamed the colony’s disintegration on ignorance, observing that Ayllón led his followers into conditions about which he assumed much but knew little, and for which he had made inappropriate preparations.

Santa Maria de Ochuse

The Spanish regarded Florida as poor, fever-ridden, and home to hostile Indians. However, for treasure ships headed to Spain from the Caribbean the strait between the peninsula’s tip and the island of Bahama was the most suitable passage, though vulnerable to conquest and control by foes. To protect his galleons and their route home, King Philip II ordered Florida secured. The King’s plan, which he worked out with Viceroy don Luis de Velasco y Ruiz de Alarcón, señor de Salinas at Veracruz, Mexico, and Tristán de Luna y Arellano, who would be executing the scheme, called for the simultaneous establishment of three colonies—on the Gulf Coast, inland, and on the Atlantic. Santa Maria de Ochuse at Pensacola Bay would control the Gulf Coast. A colony at Coosa, deep in Florida’s interior, was to grow crops to sustain all three settlements. The third colony would occupy Santa Elena, a good harbor on the Atlantic. Luna, an experienced officer of excellent reputation, departed Veracruz in June 1559 at the head of a 13-ship armada that brought some 1,500 passengers to Pensacola Bay on the Gulf. The party included aristocrats, clergy, soldiers, artisans, servants, farmers, Spanish and Indian families, and slaves. Also on board were 240 horses and 500 tons of provisions and equipment.

Leaving their food and gear aboard the anchored vessels, the settlers were beginning to build what would be Santa Maria de Ochuse when a hurricane struck. The storm sank all but the three smallest ships, which held little food. Luna sent messengers to Veracruz requesting help, but Mexico could provide little assistance. Fever spread among the colonists, including Luna, who was left deranged. Alternating between fanaticism and apathy, he disregarded all advice. Famine threatened. Hearing that an Indian village to the west had abundant crops, Luna sent troops there, informing Viceroy Velasco of this move. Starving civilians also came to the village, whose inhabitants had scant surplus food. The same proved true at Coosa. Fever continued to ravage the colonists.

Hoping relief was coming from Veracruz, Luna ordered everyone back to Pensacola Bay. More colonists died. Ships arrived but, because the viceroy thought Luna had found food, the vessels carried few provisions. They did bring orders from King Philip. Fearing France was angling to grab Florida but unaware of Luna’s desperate situation, Philip demanded that the settlers immediately colonize the harbor at Santa Elena, an utter impossibility. Still in the grip of derangement, Luna argued with everyone, prompting complaints to Viceroy Velasco. Early in 1561, a relief fleet brought food and orders relieving Luna of command. Within a short time, survivors of the two-year trial were evacuated. of their companions, nearly 1,000 had perished.

In 2015, local historian Tom Garner, exploring a construction site at Emanuel Point on the western side of Pensacola Bay, spotted pottery fragments found to date to the 16th century at what turned out to be the exact site of Santa Maria de Ochuse. Near Emanuel Point, field teams from the Florida Bureau of Archaeological Research and the University of West Florida marine archaeological program have located remains of three of the ships sunk in the 1559 hurricane.

Fort St. Louis

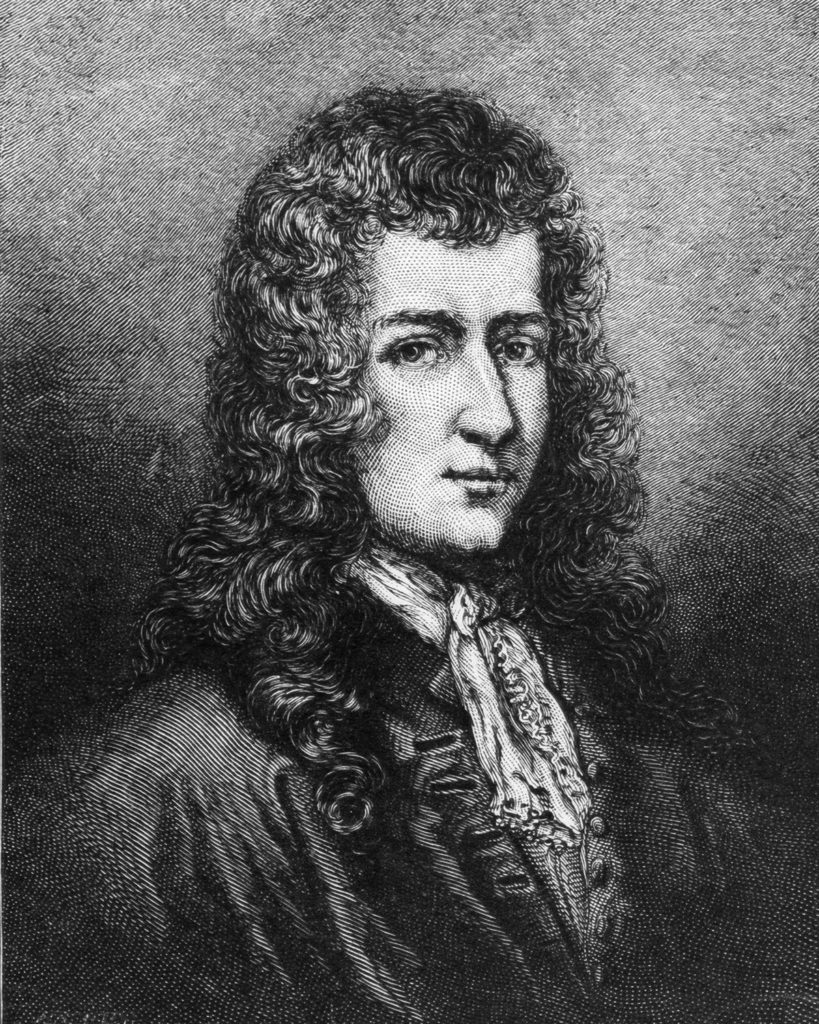

Rene-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de la Salle, led the first expedition down the Mississippi River to the Gulf of Mexico in 1682. Brave, intelligent, hardworking, and inspirational, he could be charming, but also aloof and moody. He also was given to deep depression and obsessive secrecy and attention to detail. Based on his navigation of the Mississippi, La Salle persuaded the French court to underwrite a colony near that river’s mouth, which he thought to be far west of its actual location. As he was organizing the expedition his obsessiveness intruded; he refused even to tell his ships’ captains their destination, spoiling any chance of rational preparation.

Setting sail in 1684 from La Rochelle, France, four vessels carried about 280 would-be colonists, including soldiers, clergy, artisans, orphan girls, and unskilled gentlemen. With them came various relatives, including La Salle’s own nephew, the arrogant Colin Crevel de Moranger. Aboard the overloaded vessels, passengers mostly lived on deck. At the Azores, a traditional source of provisions and water, La Salle forbade a stop. The crossing was marked by short rations and disease, and Spanish privateers captured one ship. La Salle himself fell ill but recovered during a layover at Saint-Dominique, the French colony on Hispaniola.

Following La Salle’s orders, the ships made landfall to the west of the Mississippi and then sailed much farther west. Eventually La Salle observed a sand bank between the Gulf and what appeared to be a lake fed by a river. He assumed he was seeing a tributary of the Mississippi, and that the river’s main mouth was nearby. In fact, the expedition had reached Matagorda Bay, Texas. The Mississippi was 400 miles east. La Salle decided to establish a settlement at their present location and build a second when he found the Mississippi. The smallest of his ships entered the bay, but the supply ship ran aground and broke up. The third and largest vessel was to return to France after delivering the colonists. Its captain offered to fetch provisions from Saint-Dominique but La Salle, out of pride or miscalculation, rejected the offer.

The ship sailed, taking along colonists who wished to return to France; about 200 settlers remained with La Salle. The colonists salvaged what they could from the supply ship, including eight cannons. The local Kanakawa Indians collected flotsam that had drifted ashore. Initial contact with the Kanawaka had been peaceful, but when La Salle sent nephew Moranger to recover the material the Indians had scavenged, the younger man aggressively seized the recovered goods and stole hides and canoes. That night, in retaliation, the Kanakawa raided Moranger’s camp, killing and wounding men, in effect declaring war. The colonists huddled in a makeshift fortification near the entrance to the bay. The groundwater was brackish, and dysentery ravaged them.

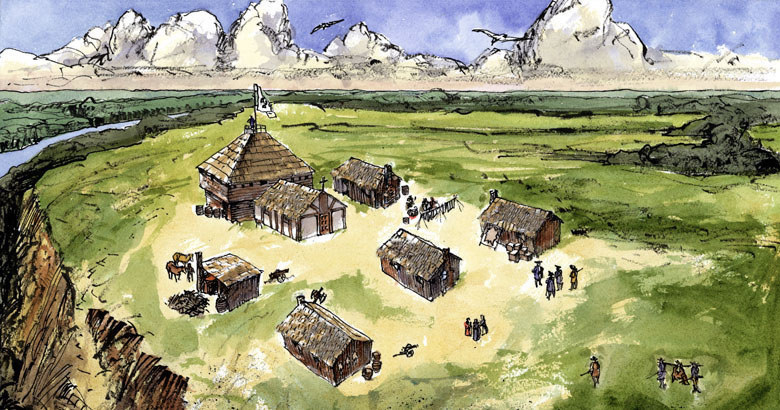

In spring 1685, La Salle departed to search for the Mississippi and a site for a settlement out of sight from Spanish ships. Not finding the big river, he chose a spot upstream from the bay on a smaller river. The new site came to be called Fort St. Louis. The surviving 150 colonists moved there. That fall La Salle again searched without success for the Mississippi. Provisions grew scarce; the colonists hunted deer and bison. Colonists continued to die by drowning and being trampled, Kanakawa ambushes, snakebites, eating poisonous plants, and disease. Men deserted or disappeared. The colonists’ remaining ship ran aground in the bay and broke up.

La Salle finally realized the Mississippi must be much farther east than he had thought. In January 1687, he set out by land in that direction. His company included Moranger. By mid-March, provisions had run short. Men killed two bison and boiled the animals’ innards to make broth traditionally given the hunters who had felled prey, but Moranger announced he would decide who ate what. That night the hunters killed Moranger and two others loyal to La Salle, and in morning murdered La Salle. The killers turned on one another; the others continued east.

Five survivors of La Salle’s expedition not involved in the murders reached the Mississippi and eventually France. Learning of the French colony, the Spanish sent forces by land and sea. These troops found buildings but no people. The Kanakawa had overrun the colony, sparing only the children whom they adopted. Before departing, the Spanish buried the colony’s cannons. Spanish rescuers retrieved ten survivors, five of them children.

In 1995, a ranch hand working near Victoria, Texas, discovered the buried cannons. Archaeologists working in Matagorda Bay subsequently located the remains of La Salle’s smallest ship, including a portion of the hull, bronze cannons, crates of trade goods, and two skeletons.

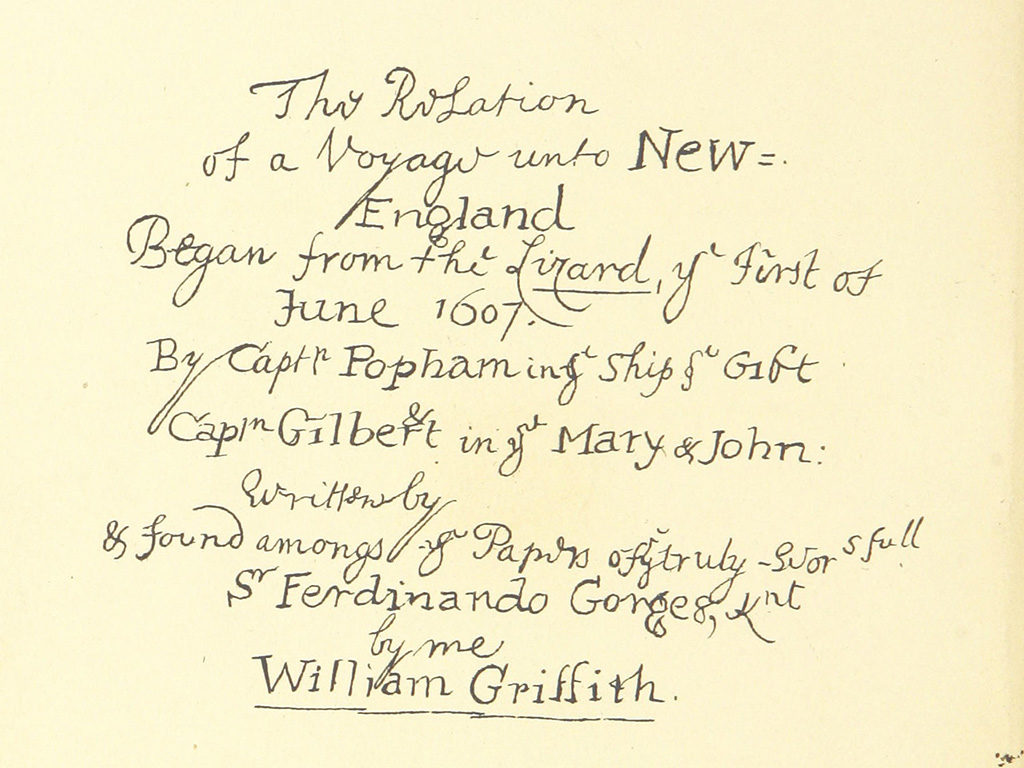

Sagadahoc

In 1606, King James I of England chartered two colonies in North America. Jamestown in Virginia survived, though at terrible human cost. The other enterprise took form at the mouth of the Sagadahoc—now the Kennebec—River on the coast of Maine. The Sagadahoc undertaking began strongly, well-funded and equipped by investors betting that besides projecting British power in North America their colonial surrogates would ship back gold, silver, and copper, find exotic spices and medicinal herbs, establish a fur trade, and perhaps even discover the Northwest Passage.

In 1607, 120 colonists set out from Plymouth, England, in two ships. Arriving on the Maine coast without problem, the settlers quickly built substantial buildings and a defensive perimeter. They had landed during what climatologists now call the Little Ice Age; the winter of 1607-08 was the coldest in a cold century. The colonists survived and never had to defend their palisade, but trouble came anyway.

George Popham was the colony’s official head. A contemporary described him as “an honest man, but ould, and of unwildy body, and timerously fearfull to offende or conteste with those that will or do oppose him, but otherways a discreete carefull man.”

Popham badly misread his new circumstances. Late in 1607, he wrote enthusiastically to King James claiming the region produced nutmeg, cinnamon, and cochineal, a rare dye extracted from insects found in Brazil and Central America. Popham told the monarch the local Indians were eager to become royal subjects and that they wished to convert to Christianity, and that the Pacific Ocean was only seven days journey west of the colony. None of this information was accurate. The colonists mistook local plants of no value for species highly sought-after at home. The native Etchemin and other tribes in the area were peaceful but uninterested in the colonists. The Indians did harvest furs, but traders from France and other nations were already established in the vicinity. The Northwest Passage was a European fantasy, and the tiny coastal colony hardly presented a good case for British imperial ambitions.

Second in command was Raleigh Gilbert, described as “desirous of supremacy, and rule, a loose life, prompte to sensuality, litle zeale in Religion, humerouse, head stronge, and of small judgment and experience, other wayes valiant inough.” Gilbert, whose late father had held a royal grant, attempted on that basis to take over, a rebellion the sponsors in England quashed, though pro-Gilbert and pro-Popham factions remained. In February 1608, Popham died, leaving Gilbert in charge—until family matters demanded his return to England. A fire claimed most of the colony’s provisions; the settlers avoided famine by sending 45 men to England. in 1608 the colonists gave up and left for England.

The Sagadahoc settlement site’s location was always known but archaeological digs found little until 1994, when Jeffrey P. Brain brought a team to the site. Brain and crew confirmed the orientation of a 1607 plan of the colony. Besides identifying specific buildings and construction techniques, excavators recovered artifacts. Much of the colony site remains unexplored. Portions lie under a road and parking lot; other areas, including the location of a chapel at which George Popham likely lies buried, are on land whose owners refuse permission to excavate.

This post contains affiliate links. If you buy something through our site, we might earn a commission. Thanks!