Groundbreaking code breakers

With regard to your Winter 2015 Weapons Check, “Bombe vs. Enigma,” I would like to note that the foundation for cracking Enigma machine ciphers was laid by Polish cryptographers, who invented the first so-called cryptologic bombe—ahead of the outbreak of World War II. They were Marian Rejewski, Jerzy Różycki, and Henryk Zygalski, and the mechanical-electrical tool they designed automatically broke cables encrypted with the Enigma. It was unique because it used mechanical ciphers as well as a special mathematical equation the cryptographers devised.

Rejewski, a civilian mathematician working at the Polish General Staff’s Cipher Bureau in Warsaw, took advantage of a weakness in the German encryption procedures: The encrypted key for the message was included at the beginning of a message. Initially, Rejewski applied a manually created directory containing all possible rotor settings. Later, when the Germans made a minor change in the encryption system and the directory became obsolete, he came up with the idea of using data from a particular day to reproduce initial rotor settings.

Polish intelligence first revealed the bombe to the Brits and the French on July 26, 1939, at a meeting in Warsaw. Its detailed plans and two Enigma replicas were then sent through Paris to London. In the autumn of 1939, the cryptographers from Bletchley Park managed to construct a sufficient number of bombes and make them more effective, thanks to the most important contribution by brilliant Alan Turing.

Mateusz Sakowicz

Permanent Mission of Poland

to the United Nations

Although Britain’s Bletchley Park operation was indeed “brilliant,” it’s important to remember other contributions to this code-breaking success, including by the Poles. In his book Battle of Wits: The Complete Story of Codebreaking in World War II, author Stephen Budiansky recounts a story from summer 1939, when a contingent of French and British cryptanalysts traveled to Poland to discuss Enigma. The Poles astounded their visitors by unveiling the Enigma machines they had built from scratch.

David Gonnerman

Northfield, Minnesota

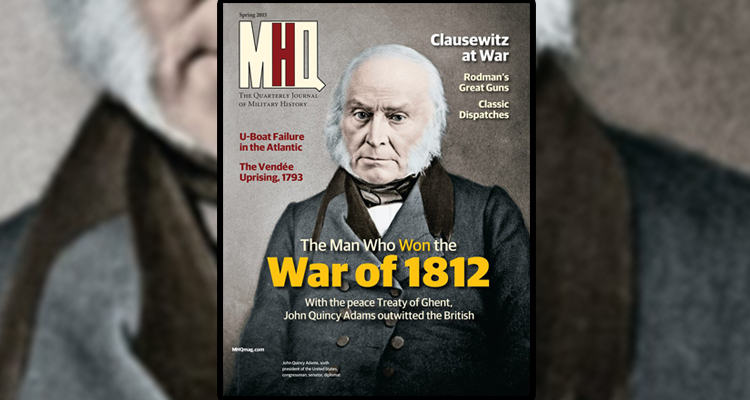

Winners and losers

In response to the coverline—“The Man Who Won the War of 1812”—for your Spring 2015 story about John Quincy Adams’s role in brokering the Treaty of Ghent, I have to say that I rather doubt he did. Not a single aspect of America’s declaration of war was met, leaving status quo and victory to Britain and Canada, who also liberated 3,000 slaves, sent them to freedom, and then paid for them at top dollar rather than return them to slavery. In all, a military, political, and moral victory for Britain and Canada.

Ricky Phillips

via Facebook

More lessons of the Vendée

Anthony Brandt’s article “Lessons of the Vendée,” [Spring 2015] deals with a “lost cause” that in terms of historical memory, interpretation, and commemoration exceeds even those of Scotland and the American South. Napoleon would refer to the events in the Vendée—the most serious internal challenge faced by the newborn French Republic—as a guerre de géants (a “war of giants”) and he studied the Catholic and Royal Grand Army of the Vendée’s crossing of the Loire River in October 1793 as an example of tactical brilliance under fire. War in the Vendée also presaged the type of guerrilla war French forces would face in Haiti, Southern Italy, and Spain. Lenin studied the Republic’s response to dealing with recalcitrant peasants, clergy, and nobles for useful lessons in dealing with his own revolutionary problems.

A small group of modern French writers, historians, and politicians is campaigning to have the victims of the Vendée recognized as “the first victims of genocide in modern history,” although the American historian David A. Bell has categorically stated: “The war in the Vendée was not a genocide. That, however, is probably the only positive thing that can be said about it.” The best English-language summary of the wars of the Vendée can be found in “The Exterminating Angels,” chapter 5 of Bell’s The First Total War (2007). Two 19th-century novels also provide interesting insights into the Vendée. While a bit thin on plot, Victor Hugo’s novel Ninety-Three (1874) does convey excellent descriptions of war in the bocage, village life, and Vendéan leaders. Anthony Trollope’s La Vendée (1850) is remarkably perceptive about the problems of peasant soldiery and the military odds against the Vendéans, yet his British views and background are also readily apparent.

Emory Earl Toops

Fort Wayne, Indiana

We welcome your comments. Visit MHQmag.com or e-mail MHQeditor@historynet.com. Letters are edited for length and clarity.