During the siege of Savannah, a heavily defended Confederate bastion fell to infantrymen with rapid-firing Spencers

ON DECEMBER 13, 1864, Union infantrymen in Brig. Gen. William Babcock Hazen’s 2nd Division lined up to assault Fort McAllister, a Confederate stronghold on the right bank of Georgia’s Ogeechee River, near Savannah. Hazen’s division—one of four in Maj. Gen. Peter J. Osterhaus’ 15th Corps, which comprised half of Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman’s Right Wing during his March to the Sea from Atlanta—had been instructed to “take the fort by storm.”

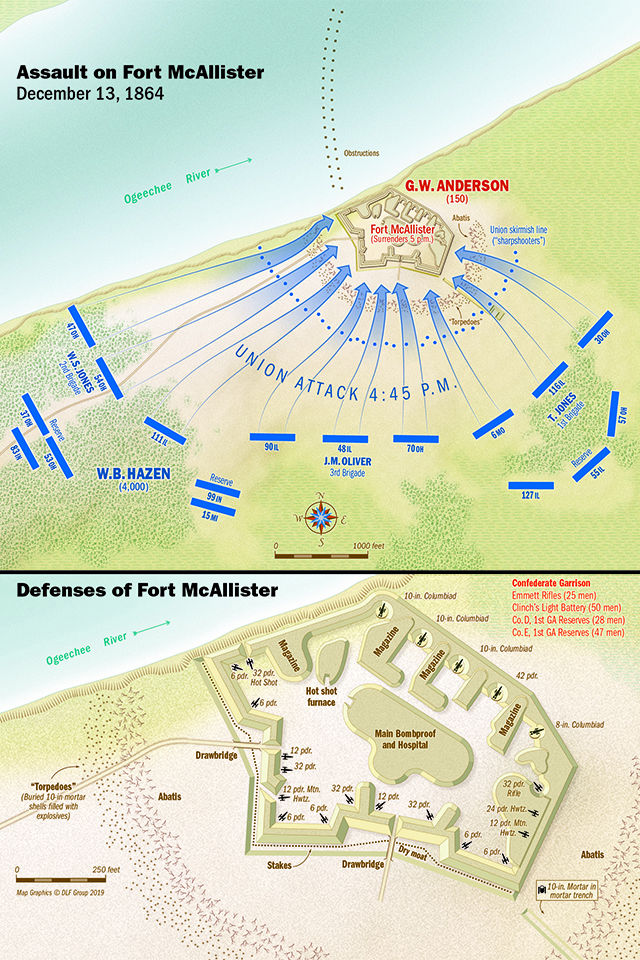

For Hazen’s 3,000 or so men, it was a formidable challenge. Thirteen of McAllister’s 22 heavy guns were positioned on the earthen fort’s landward side, including various 32- and 42-pounders, several 8- and 10-inch Columbiads (designed to fire 65-pound and 128-pound projectiles, respectively) and even a 10-inch seacoast mortar capable of firing 88-pound explosive shells. As an integral part of Savannah’s Atlantic Coast defenses, the bastion had heavy gun emplacements designed mainly to facilitate rapid and accurate cannon fire in case of Union naval attacks. All the same, these guns could be highly destructive against infantry assaults, especially when firing grapeshot.

Surprisingly, as Hazen’s infantry formed only 500 yards out, the daunting weapons were essentially silent. The reason why was the result of events that had played out over the previous few days.

As “Cump” Sherman’s 28,000-man Army of the Tennessee—made up of the 15th and 17th Corps—approached Savannah near the end of the march, it became clear that capturing the heavily fortified port city would not be routine—certainly not compared to some of the Federals’ endeavors over the preceding 28 days. “[A]t Savannah we had again run up against the old familiar parapet, with its deep ditches, canals, and bayous, full of water; and it looked as though another siege was inevitable,” Sherman wrote in his memoirs. “As soon as it was demonstrated that Savannah was well fortified, with a good garrison, commanded by [Lt. Gen.] William J. Hardee…I saw that the first step was to open communication with our fleet, supposed to be waiting for us with supplies and clothing in Ossabaw Sound.”

Sherman understood Fort McAllister was critical to unlocking Savannah’s defensive ring, and as long as it remained in Confederate hands it blocked the general’s ability to communicate with Rear Adm. John Dahlgren’s South Atlantic Blockading Squadron patrolling outside the port. Capture of McAllister would also provide a pipeline to essential supplies, as the Ogeechee River was deep enough to allow access to Union transport vessels.

According to author Noah Andre Trudeau, in his 2007 book Southern Storm, “Food supplies continued to be their biggest problem, and each day made the situation more acute.” Lieutenant William Pittenger of the 39th Ohio wrote in his diary: “Our last issue of bread expired last night which makes it necessary to do our work quickly. Must eat to fight. We must take Savannah or reach a base very soon. Time is precious.”

Sherman was confident Fort McAllister was vulnerable to a land assault as long as its large garrison was not given sufficient time to prepare, and his guarded optimism was shared by his Right Wing commander, Maj. Gen. O.O. Howard, and Cavalry Corps chief Brig. Gen. Judson Kilpatrick. On December 11, Trudeau writes, Sherman proposed having Kilpatrick’s cavalry launch an attack on the fort, getting a tepid response from Kilpatrick, who was certain he would need infantry support to do so. “I have proposed to General Howard to cross the Ogeechee with my command and a force of infantry and take the fort,” Kilpatrick would write Sherman. “I am certain from what I learn that I can take it, and once done the fleet can come up to within two miles of General Howard’s right. Boats will then be at our disposal….General Howard has accepted my proposition, will give me the infantry asked for, and I only now await your permission. I promise to take the fort.”

On the 12th, Kilpatrick wrote Sherman again: “I did not intend, general, to attempt the capture of the fort by a sudden dash, but I intended to deliberately storm the works. I have old infantry regiments, armed with Spencer rifles, who could work their way up to within easy range and force every man to keep his head beneath the parapet, and, finally, force my way into the fort—of course, I intended to maneuver my troops as infantry.”

It is interesting that in his own memoirs Sherman excluded any mention of that Fort McAllister communication as well as any responses he may have sent to Kilpatrick. Trudeau writes, however, that Sherman ordered his cavalry chief to fall back from the fort and have a portion of his command attempt to communicate with Union ships in St. Catherine’s Sound. The rest of Kilpatrick’s troopers were sent to the deserted colonial port of Sunbury, Ga., which Sherman was considering as an alternate access point to the Navy off shore.

On December 11, Howard had stealthily sent a canoe, manned by a small group of scouts, down the Ogeechee past the fort to assess its condition and defenses. At full strength, the garrison had counted 230 men, but it had been reduced to about 150 by this point—still formidable because of those 22 heavy guns.

Howard also succeeded in making contact with Dahlgren, who informed him on the 13th: “I have two ironclads at Wassaw and a force of gun-boats at Ossabaw and [the] Savannah River; will await your movements to establish a communication…”

During a landward attack on McAllister, Hazen had two primary tactical advantages. First, the fort’s guns were mounted en barbette (i.e., in open mountings firing over a low parapet). This left the crews responsible for firing and reloading the weapons dangerously exposed to enemy fire. Second, the weapons of choice for the 15th Corps’ skirmishers were the Spencer and Henry repeating rifles. The Spencer, both in rifle and carbine versions, used seven-round tubular magazines; the Henry’s magazines contained 16 rounds. The single-shot, muzzle-

loading rifle-muskets wielded by many of the fort’s support infantry would be generally inadequate against such rapid-fire capability.

On the morning of December 12, Major George Wayne Anderson, the fort’s commander, discovered that Sherman’s forces had advanced as far as King’s Bridge—13 miles northwest of the fort. Anderson immediately had trees surrounding the bastion, as well as nearby homes and other structures, cut down to open a better field of fire; however, he later wrote that “[f]or lack of the necessary force and time…the felled timber and the ruins of the adjacent houses which had been pulled down, had not been entirely removed.”

If this terrain around the fort had been cleared away earlier, it would have strengthened its land-oriented defenses. Instead, because of the incompletely cleared fields and the exposed nature of the fort’s gun positions, Hazen’s men had a textbook opportunity to allow their skill with rapid-firing weapons to take deadly effect.

A Union soldier in the 20th Corps wrote that he and his comrades felt confident their Spencers were “good for any two rebs in Dixie.” Kilpatrick was apparently so taken with the carbine’s effectiveness at Fort McAllister that on January 3, 1865, he expressed his disappointment with the breechloading, single-shot Joslyn and Sharps carbines that some of his men carried: “The Joslyn Carbine, with which the Ninth Pennsylvania is armed, and the majority of my Sharps carbines, are utterly worthless. I earnestly request that 300 Spencer carbines be sent to this point, with as little delay as possible. My troops are worse armed at present than [Confederate Lt. Gen. Joseph] Wheeler’s irregular, lawless cavalry.”

The 16-round, lever-action Henry rifle was a particular favorite of the 15th Corps. In fact, on December 7, six days prior to the Fort McAllister assault, a 1-ton supply wagon was allocated merely to transport the massive amount of ammunition the Henry needed.

The Union attack on December 13 began at 4:45 p.m. Skirmishers advancing ahead of their respective regiments at the head of the assault included infantrymen designated by their officers and sergeants as “sharpshooters.” These riflemen, unlike elite units such as Colonel Hiram Berdan’s famed 1st and 2nd Sharpshooter Regiments, had received no specialized training, nor had they been required to pass any rigorous marksmanship qualification tests. Typically farm boys who had grown up hunting rabbits, squirrels, and deer, they simply had shown superlative skill with their guns in previous combat.

Among the skirmishers was Captain William E. Brachmann’s Company F of the 47th Ohio. The men rushed to firing positions about 200 yards from the fort, then hid behind the tree stumps and other debris left on the ground. Impeccably concealed, the skirmishers could soon wreak havoc on the Confederate artillerymen attempting to fire and reload the huge guns.

Sherman, watching from a vantage point atop an abandoned rice mill across the Ogeechee, later expressed satisfaction at his good fortune due to that debris. According to Captain Orlando M. Poe, Union skirmishers threw “themselves flat on the ground [where] they were well concealed by the high grass and could pick off the rebel gunners at their leisure, readily silencing the fire of the fort.”

Added Major George Ward Nichols, of Sherman’s staff: “There were twenty-one [sic] guns…in the fort…and the deadly aim of our sharpshooters had killed many of the garrison at their pieces. The artillery did very little execution.”

Among the defenders paying the price in this initial onslaught was an eight-man detachment that lost three members killed and three wounded. “The Federal skirmish line was very heavy, and the fire so close and rapid that it was at times impossible to work our guns,” Major Anderson would write.

At 5 p.m., 10 of the 17 regiments in Hazen’s division formed for an advance. Captain Brachmann and his fellow commanders ordered their men to fire as rapidly as possible and continue firing until they drew level with the skirmishers, who were then to take their place within the regimental lines and join the attack on the fort.

With bugles sounding and the enemy’s heavy guns all but silenced, Sherman recalled seeing “Hazen’s troops come out of the dark fringe of woods that encompassed the fort, the lines dressed as on parade, with colors flying, and men moving forward with a quick, steady pace.” Nichols described the thrill of witnessing “bright bayonets, and the dear old flag….”

The Federals advanced more or less unmolested across the remaining quarter-mile open area before the fort, although these men faced another significant concern— “land torpedoes,” or improvised explosive devices, planted in the ground by the Confederates. These torpedoes, what we know today as mines, had been invented, developed, and championed by Confederate Brig. Gen. Gabriel J. Rains and, understandably, were feared by enemy soldiers.

“The fort,” Poe wrote, “was provided on its land front with a good ditch, having a row of stout palisades at its bottom, well-built glacis, and a row of excellent abatis, exterior to which was planted a row of [buried] 10-inch [mortar] shells designed to explode when trodden upon. These shells were arranged in a single row just outside the abatis and were about three feet from center to center. It was impossible to move an assaulting force upon the fort without suffering from the explosion of these shells.”

Nevertheless, within 15 minutes, the Union troops had carried McAllister “by storm,” with Hazen reporting 24 of his soldiers killed and 110 wounded while the Rebel garrison’s casualties were complete at 150. Three days later, Sherman wrote to Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, Union Army general-in-chief, that “[a]t the time we carried Fort McAllister by assault so handsomely—with its 22 guns and entire garrison, I was hardly aware of its importance: but since passing down the river with [Maj.] Gen. [John G.] Foster and up with Admiral Dahlgren, I realize how admirably adapted are Ossabaw Sound and [the] Ogeechee [R]iver to supply an Army operating against Savannah.”

Beside Sherman’s advantage in overall numbers, the Union victory could be chalked up to three major factors.

As mentioned above, Anderson had not been afforded enough time to construct proper defenses and to properly clear the fort’s landward approaches. Major Nichols recounted a conversation he had with the Confederate commander after the battle: “Major Anderson…tells me that he did not anticipate an assault tonight [sic] and was hardly prepared for it when it came.”

Wrote Nichols, “Had we waited, built intrenchments and rifle-pits, and made the approaches which attended siege operations, we would have lost many men, and much time; and time at this crisis of the campaign is invaluable.”

The second factor, as noted above as well, was the fort’s open gun mountings. Though the artillery crews had the flexibility to maneuver their guns rapidly and threaten ships approaching on the Ogeechee River, the men were exposed to enemy fire. Without protective embrasures, a Union soldier wrote, “It’s of no use; you can’t defend a work of this sort with guns en-barbette.” Kilpatrick made sure to note that Union sharpshooters could “force every man to keep his head beneath the parapet.”

Third: Without the 47th Ohio’s marksmen and others in Hazen’s skirmish line, Union casualties would have been much higher. This was so evident it was stressed in just about every eyewitness account. “[S]o effective was the fire of our skirmish line,” a 47th Ohio soldier declared, “altogether our regiment [merely] had to pass over the cleared ground and climb the fence; very little damage was done.”

With Fort McAllister now in Union possession, Sherman had a secure supply line to use in capturing Savannah, supported by Dahlgren’s warships. Sherman moved into position his Army of the Tennessee and Army of Georgia—four corps in all—and on December 17 demanded General Hardee surrender his army and the city. Hardee instead chose to pull out, evacuating his troops on a pontoon bridge across the Savannah River on December 20. The next day, a civilian delegation led by Savannah Mayor Richard Arnold surrendered the city, which Union troops occupied later that day. On December 22, Sherman wired an anxious President Abraham Lincoln with the good news:

I beg to present you, as a Christmas gift, the city of Savannah, with 150 heavy guns and plenty of ammunition, and also about 25,000 bales of cotton.

Isaiah L. Reed , who writes from Nebo, N.C., is the author of The Forgotten Act: General Sherman’s Special Field Order No. 15 (2016). He has been fascinated by Sherman’s Civil War activities in Georgia since he was 13 years old, and is a collector of antique books about the Union general.

_____

‘Heart of a Lion’

The Federals used so much ammunition during their initial push on Fort McAllister, they nearly ran out. That, however, led to incredible heroism by one 47th Ohio soldier. That unit’s regimental history divulged:

“One of the bravest acts that came under my observation during the war was performed by Louis Shuttinger of Company A. He was on the skirmish line just before the assault on Fort McAllister, and the skirmishers ran out of cartridges. Shuttinger volunteered to go for some; when he got to where the ammunition was, he pulled off his blouse and filled it with packages of cartridges, and returned under cover of the river bank until he reached the end of the line, which deployed at right angles to the river; here he was compelled to get on top of the bank, and in full view of the enemy, so he called out, ‘Keep them down, boys, here I come’ and deliberately walked along the line dropping the cartridges to the men as he passed. Even the Confederates seemed to think him too brave to shoot at. Shuttinger was our smallest man, but he had the heart of a lion.” –I.L.R.

“One of the bravest acts that came under my observation during the war was performed by Louis Shuttinger of Company A. He was on the skirmish line just before the assault on Fort McAllister, and the skirmishers ran out of cartridges. Shuttinger volunteered to go for some; when he got to where the ammunition was, he pulled off his blouse and filled it with packages of cartridges, and returned under cover of the river bank until he reached the end of the line, which deployed at right angles to the river; here he was compelled to get on top of the bank, and in full view of the enemy, so he called out, ‘Keep them down, boys, here I come’ and deliberately walked along the line dropping the cartridges to the men as he passed. Even the Confederates seemed to think him too brave to shoot at. Shuttinger was our smallest man, but he had the heart of a lion.” –I.L.R.

_____

Leathernecks vs. Cadets

The week prior to the Battle of Fort McAllister, Sherman’s forces fought a less successful engagement 45 miles northwest of Savannah in an attempt to cut a critical section of the Charleston-Savannah Railroad. The Battle of Tulifinny (shown above), fought December 6-9, was a rare Confederate victory during Sherman’s March to the Sea. The Confederates, outnumbered 5,000–900, defeated an assault by Union troops supported by 12 U.S. Navy gunboats and sloops of war.

Yet the battle was most notable for some of the units on both sides that participated. The Union force, composed primarily of five infantry regiments and several artillery batteries from New York and Ohio, and two USCT regiments, also included a battalion of U.S. Marines from Rear Adm. John Dahlgren’s South Atlantic Blockading Squadron. Commanded by 1st Lt. (Acting Lt. Col.) George G. Stoddard, the Leathernecks at Tulifinny fought one of the Marine Corps’ few land battles during the Civil War.

Yet the battle was most notable for some of the units on both sides that participated. The Union force, composed primarily of five infantry regiments and several artillery batteries from New York and Ohio, and two USCT regiments, also included a battalion of U.S. Marines from Rear Adm. John Dahlgren’s South Atlantic Blockading Squadron. Commanded by 1st Lt. (Acting Lt. Col.) George G. Stoddard, the Leathernecks at Tulifinny fought one of the Marine Corps’ few land battles during the Civil War.

Meanwhile, more than a third of the Confederate force (mainly Georgia and South Carolina militia regiments) consisted of the entire 343-member cadet corps of the South Carolina Military Academy (in this era comprised of the Citadel in Charleston and the Arsenal Academy in Columbia). Commanded by Maj. James B. White, SCMA superintendent, the South Carolina Battalion of State Cadets, in White’s words “acted with conspicuous gallantry and showed that the discipline of the Academy had made [every cadet] a thorough soldier for the battlefield.”

Anchoring the right flank of the Union battle line, Stoddard’s Marines suffered 11 casualties in the defeat, and on the battle’s final day directly assaulted White’s Citadel cadets—Cadet William Patterson was killed and seven other cadets were wounded. –Jerry D. Morelock