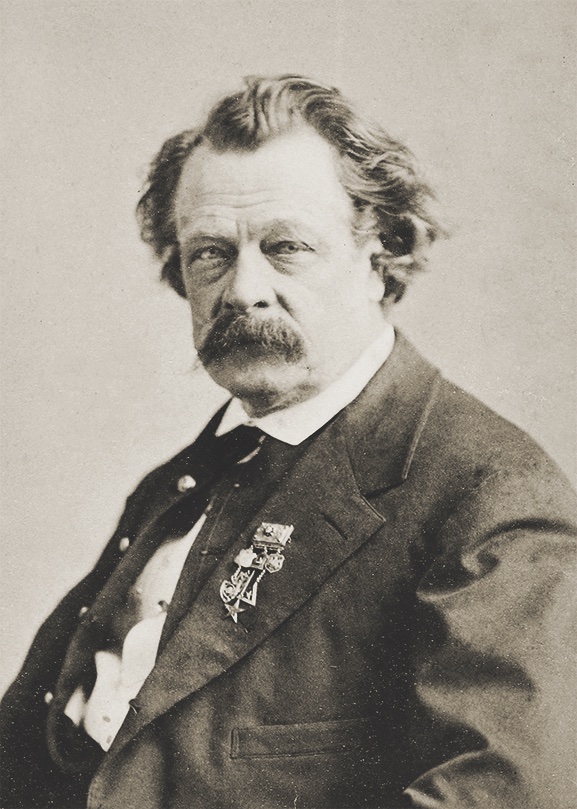

Ned Buntline is the only American novelist who was lynched by an angry mob and lived to tell the tale, although he much preferred telling fictitious tales that made him seem heroic.

In 1846, Buntline, 23, was in Nashville, Tennessee, trying to raise money for his magazine, Ned Buntline’s Own, and romancing a local teenager. Her husband, Robert Porterfield, took umbrage and fired a pistol at Buntline. Porterfield missed, fired again, missed again. Buntline shot back, killing Porterfield. When the publisher was arraigned, a mob of Porterfield’s friends invaded the courtroom, shooting. A bullet pierced Buntline’s chest. He fled the courthouse into a nearby hotel, the horde in pursuit. Cornered on the third floor, Buntline leaped out a window. Police picked the stunned, bleeding writer off the ground and carried him to jail. Porterfield’s pals broke into the hoosegow, hauled Buntline out, and hanged him from a storefront awning. But somebody cut the rope and cops hauled Buntline back to confinement.

Newspapers reported that Buntline died that night. They were wrong. He lived another four decades, during which he published a scandal-sheet newspaper, blackmailed brothel owners, led an anti-immigrant movement, incited two riots, spent a year in prison, married six women, and wrote more than 300 pulp adventure novels.

Born Edward Zane Carroll Judson in 1823, he ran away at 12 from his Philadelphia home and stowed away on a ship. He spent seven years at sea, first on merchant vessels sailing the Caribbean, then as a U.S. Navy midshipman. He began writing seafaring adventure stories and sold several under the pen name “Ned Buntline,” the latter word a nautical term referring to a rope securing a furled sail.

After leaving the Navy in 1842, Buntline edited literary magazines in Pittsburgh and Cincinnati but they went belly up. His mission to Nashville to raise seed money for another magazine got him shot, lynched, and jailed until he convinced a grand jury he’d shot Porterfield in self-defense and was freed.

He moved to Manhattan and began turning out pot-boiling yarns for pulp magazines. In 1848, he published Mysteries and Miseries of New York, a novel set in that city’s underworld of whorehouses and gambling dens. Mysteries and Miseries sold 100,000 copies and spawned several sequels. Now famous, the author started a weekly, Ned Buntline’s Own, vowing to crusade against prostitution and gambling.

He kept that promise, sort of. He exposed brothels and gambling dens, revealing their locations and sometimes naming their owners—unless they paid him off, in which case the info stayed on the down low. From brothels he was willing to accept payoffs in cash or in kind. Thus, Ned Buntline’s Own served three purposes: it exposed vice, informed readers where to find vice, and served as a lucrative blackmail ing tool. But it also created enemies.

“You dirty, mean, sneaking, paltry son of a bitch,” madam Kate Hastings yelled at Buntline as he was strolling a Manhattan street in 1849. “How dare you publish me in your paper!”

Hastings uncoiled a horsewhip and thrashed her tormenter about the head and shoulders. He squealed to police, who arrested the brothel owner. When the case came to trial, Hastings showed the judge a blackmail letter from Buntline, and got herself sprung. Rival newspapers reported the episode with palpable glee.

Meanwhile, Buntline wed a British immigrant named Annie Bennett and moved into his spouse’s prosperous parents’ home. His immigrant in-laws’ hospitality didn’t keep Buntline from attacking immigrants, particularly British immigrants, in his newspaper. In 1849, he incited a mob to attack the Astor Place Opera House to protest British actor William Macready’s appearance there in Macbeth.

The melee killed 21 people. Arrested for inciting it, Buntline drew a year behind bars, during which his wife divorced him, citing his drunkenness and infidelity. Released in 1850, he was greeted by a mob of supporters and a band playing “Hail to the Chief.” He quickly wrote a novel, The Convict’s Return, or Innocence Vindicated, then embarked on a lecture tour, sometimes orating on “Americanism,” sometimes touting temperance. Whatever the topic, Buntline seldom failed to fortify himself with plenty of pre-lecture grog.

He settled briefly in St. Louis, Missouri, where authorities arrested him in 1852 for inciting a riot against German immigrants. When that trial ended in a hung jury, Buntline jumped bail and fled before he could be retried. He spent the next decade campaigning for the anti-immigrant American Party, writing countless adventure stories and marrying a steady succession of young women. At least once, he failed to divorce one wife before marrying the next and was arrested for bigamy.

In 1862, at age 39, Buntline joined the Union army. He served in Virginia but saw little action. On a furlough in 1863, he traveled to Manhattan to visit his pregnant fifth wife Kate and their daughter. While there, he hooked up with third wife Lovanche, and promptly remarried her. Realizing that Ned, who had overstayed his leave, was already wed, Loyanche exposed him as a deserter, landing him in the guardhouse. But she visited him in stir, bringing him paper, which he filled with stories that she sold to the New York Weekly. Honorably discharged as a private in 1864, Buntline, claiming to have made colonel, wrote Life in the Saddle or The Cavalry Scout, a wildly exaggerated account of his wartime adventures.

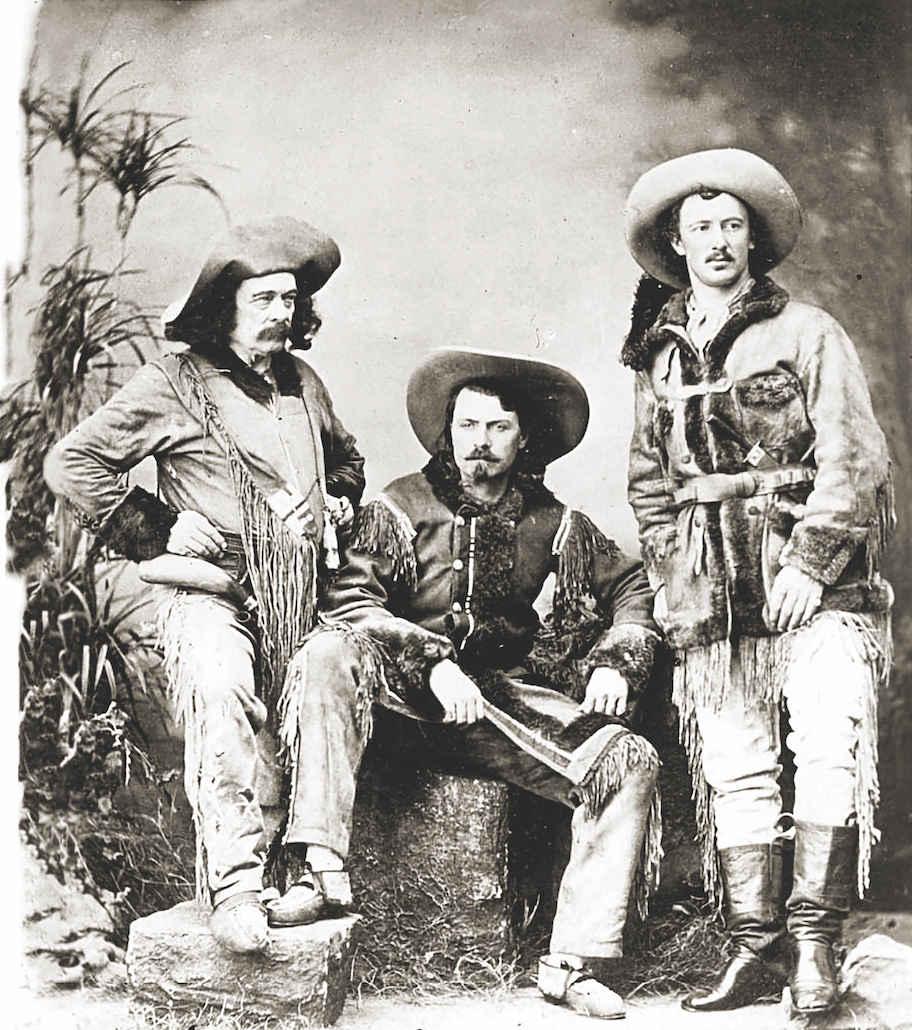

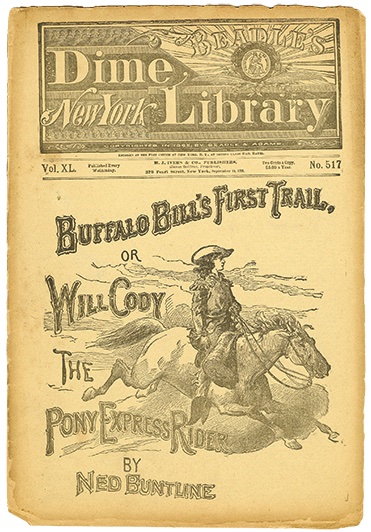

On the lecture circuit again in 1869, Buntline was in Nebraska when he met a real cavalry scout—William Cody, 23. The two rode and hunted together and Buntline rushed out several dime novels about the man he dubbed “Buffalo Bill.” The books made Cody famous, so Buntline wrote a play, “Scouts of the Plains,” starring himself and Cody and some ersatz Indians. Critics mocked the production—“…so wonderfully bad it was almost good,” said the New York Herald—but “Scouts” drew crowds and launched Cody’s career as a showman.

For the next 15 years, Buntline lived in upstate New York with his sixth and final wife, churning out dozens of dime novels. He worked fast.

“I once wrote a book of 610 pages in 62 hours,” he bragged.

His oeuvre, mostly adventure yarns aimed at boys, sold hundreds of thousands of copies and made him rich.

Every Fourth of July, the “Ten Cent Millionaire” treated his Stamford, New York, neighbors to a dazzling fireworks display. He also entertained folks in local bars with dubious stories of his adventures. Sometimes he’d bare the scar on his chest from that 1846 Nashville courtroom fracas, then tell listeners he’d gotten it battling pirates or Indians or Confederates.

When Ned Buntline died in 1886, at age 63, the New York Mercury called him “the most sensational, and in some respects, the most thoroughly ‘American’ American of his time.”