MARINE FIRST LIEUTENANT Richard S. Collum was reading the April 14, 1865, morning paper after a quiet breakfast in his quarters at the Marine Barracks when he spotted an announcement about a live performance at Ford’s Theatre, Washington, D.C.’s “magnificent thespian temple.” The play, Our American Cousin, headlined by popular British actress Laura Keene, was billed as an eccentric comedy. According to the announcement, “President Lincoln, General Grant and other distinguished men would be present.” On the spur of the moment, “I determined to go,” Collum remarked.

Collum, 27, had been a Marine since 1861. During the war he served in the Atlantic and participated in the attacks on Fort Fisher, near Wilmington, N.C. After commanding the Marine guards at the Washington Navy Yard in1865, he served at Mound City, Ill., and Boston. In Washington after General Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Court House, Va., Collum thought it would be a good opportunity to see the two men who had led the Union to victory. A relaxing evening at the theatre also offered him a welcome respite from the hectic duties of the past few days. Lee’s surrender five days before had unleashed the emotions of the war-weary residents of the capital. They had exploded in riotous celebrations, often leading to drunken bouts of mayhem, which Collum’s men at the Washington Navy Yard had to bring under control.

Another barracks officer, Major George R. Graham, agreed to accompany Collum to the theatre. Graham suggested that they stop off at the Kirkwood House, an upscale hotel at the corner of Pennsylvania Avenue and 12th Street, whose current residents included Vice President Andrew Johnson.

The two men left the barracks about 6 p.m. and leisurely strolled past the joyous crowds to the hotel. After buying drinks, they made their way to the reading room to relax and watch the patrons come and go. At about 7 p.m. “a man in dark clothes with spurs on his boots briefly spoke to the major and then entered the bar,” Collum recalled. Graham explained that he knew the man’s father: “He used to work as a clerk at the Navy Yard. His name is Herold—a ne’er-do-well.”

Neither Collum nor Graham was yet aware that David Herold was part of a group of Confederate sympathizers that was planning to kill the president. Nor did they know that John Wilkes Booth, the leader of the conspiracy, had gone to the Kirkwood about an hour earlier and left a note for Johnson. It was part of Booth’s plot to kill not only Lincoln, but also the vice president and Secretary of State William H. Seward.

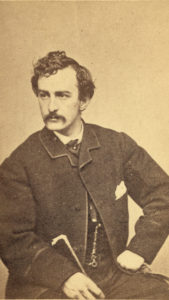

Booth, a 26-year-old actor, came from a family of famous Shakespearean players. He had a lean and athletic build, and curly black hair that framed his face. Called by some “the handsomest man in America,” Booth won his celebrity status by his romantic personal attraction. By this time, he had performed on the stages of major American cities from New York to Richmond, Va.

Booth had frequently performed at Ford’s Theatre, and as a result, he was well acquainted with the staff. He knew William Withers, leader of the orchestra and former member of the Marine Band, as well as some of the players, who were moonlighting Marine bandsmen. Since Booth was the leader of the conspiracy and knew the layout of the theater like the back of his hand, he would carry out the plan to kill Lincoln. He enlisted the assistance of David Herold, a clerk at a nearby drugstore and a skilled horseman. Knowing the back roads of the countryside south of Washington, D.C., he would help Booth escape.

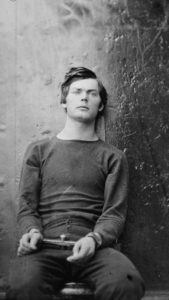

George Atzerodt, a young carriage painter with a weakness for drinking, was supposed to shoot the vice president. Lewis Powell, who had had been going by the name Payne since he deserted from the Army of Northern Virginia, was assigned to murder Seward in his home. Other accomplices included John Surratt, who acted as a Confederate courier, carrying military secrets, and his widowed mother, Mary Surratt, who ran a boarding house frequently used as a meeting place for the conspirators. In preparation for the evening of evil deeds, Booth had purchased a horse and placed it in the stable behind Ford’s Theatre, where it would be waiting so he could escape.

Collum and Graham walked the two blocks to Ford’s Theatre on 10th Street, arriving in time for the 8 p.m. showing. As they entered the lobby, they were immediately taken in by the ebullient mood of the crowd—ladies in their elegant evening dresses, men in black tie, soldiers and Marines in their brass-buttoned uniforms—talking and laughing excitedly as they waited for the performance to begin.

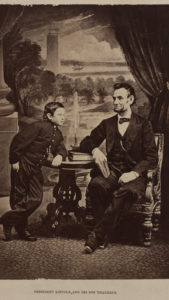

The two officers found their seats three rows from the stage on the left side; from there they had a good view of the president’s box in the second level on the right side. They were fortunate to get good seats, because the house was packed “from pit to dome” with an audience of approximately 1,600. The curtain had already risen for the play when Lincoln and his wife, Mary, arrived with their guests, Army Major Henry Rathbone and his fiancée, Clara Harris, the daughter of Senator Ira Harris of New York. The young couple had replaced Lt. Gen. Ulysses Grant and his wife, who had declined the invitation earlier that day so that they could visit their children in New Jersey.

As the president entered his box, the play was stopped. The orchestra leader, William Withers, raised his baton, brought it down dramatically and the orchestra struck up “Hail to the Chief.” The audience clapped and cheered; Lincoln smiled in appreciation. The play resumed. Collum later recalled that he saw Booth walk down the left aisle to the edge of the stage, where he turned and “took in the situation with an apparently cool and critical eye.” He was dressed in an evening suit with a white satin waistcoat and departed as quickly as he had arrived. This fleeting appearance made little impression on the two Marines at the time.

During the intermission, Collum noticed that Lincoln was chatting with his guests and appeared to show “a buoyancy of spirits, greatly in contrast to his usual manner.” In a terrible breach of security, John Parker, the policeman sent by the White House staff to accompany the Lincolns for the evening, went for a drink after the first act and did not return to his station. Before the second act, Collum noticed that “Lincoln arose laughing from his chair” to put on his overcoat and then settled into his seat. Years later Collum wrote: “The dread shadow of death was even then…approaching and soon its icy hand would blot out forever a noble life.”

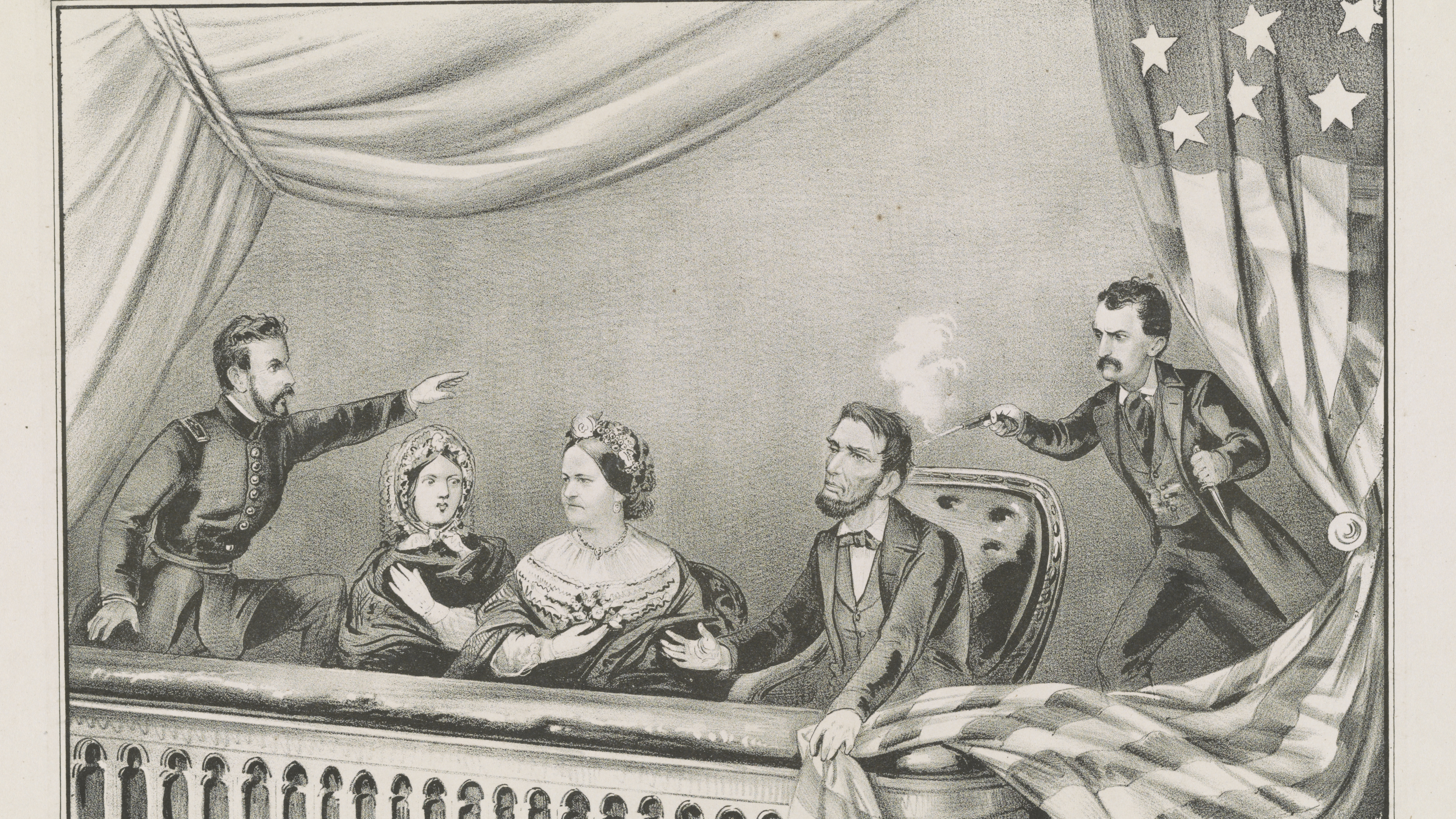

The theater darkened as the curtain rose for the resumption of the comedy. Halfway through Scene Two of the third act, Harry Hawk, the actor on stage, delivered one of the play’s funniest lines. Just as the audience laughed, “a muffled pistol shot was heard.” Collum thought it came from behind the curtain, but then suddenly “a woman’s piercing shriek rang out, a noise of scuffling in the president’s box was heard and immediately an agile form sprang from the rail of the box.”

It was later determined that while all the audience had been focused on the play, Booth had slipped into the narrow hallway leading to a door opening on the presidential box. He carefully placed a wooden block across the door, so that it couldn’t be opened from the outside. He then opened the door to the box, aimed his Derringer and fired a single shot into the left side of Lincoln’s head.

Rathbone lunged for Booth, who dropped the pistol and pulled a long knife out of his boot. As the blade ripped open Rathbone’s upper arm, the major fell backward just as Booth leaped up on the rail. Collum recalled how Booth stood for a second with a knife in his uplifted right hand “to shout in stentorian tones those memorable words Sic semper tyrannis” [Thus always to tyrants], and jumped 12 feet down to the stage. His spur caught in the flag draping the railing of the presidential box, causing him to fall off balance and break his leg just above the ankle.

Limping badly, Booth rushed to exit the stage, “facing the audience as he passed, his eyes glaring with the wild light of insanity and disappeared from view,” Collum wrote later. Clara Harris cried out, “He has shot the president!”

Several men tried to pursue Booth through the backstage passageways, but he slashed anyone who got in his way. As he came up to orchestra leader Withers, who was backstage at the time of the shooting and still totally unaware of what had happened, Booth yelled hysterically: “Let me pass!”

“He made a rush at me…waving his dagger [that] cut a gash through the left side of my coat,” Withers later recounted. Booth slashed again, cutting the orchestra leader’s shoulder, and shoved him, sending him “sprawling to the floor.” Withers recalled: “As I lay there on the floor, I wondered in a vague sort of way what I had done to Booth that he should want to murder me.” Booth ran to the alley exit, jumped on his horse and galloped into the night.

Wild confusion and shock rippled through the audience. Collum and Graham saw people crying, cursing and calling for vengeance. Laura Keene stood in the footlights and “with uplifted hands to heaven cried in impassioned tones: ‘Kill him! Kill him!’”

Meanwhile, several doctors from the audience eased Lincoln from his chair and placed him on the floor, where they examined his wound. The doctors permitted Keene to rest the president’s bloody head in her lap. As soon as it was determined Lincoln had to be taken to a more suitable place, a few men carried him down the steps in the theater. Initially, the doctors were going to move Lincoln next door to the Star Saloon, but decided against it. The saloon was jointly owned by two members of the Marine Band, Peter Taltavull, one of the best French horn players in the country, and Scipiano Grillo. Just before show time, Withers had gone for a drink at the bar and Booth was the first person he met. “He was standing at the bar in his shirtsleeves, his coat thrown over one arm and his hat in his hand,” Withers recalled. Someone made a joke at Booth’s expense. “I remember seeing an inscrutable smile flit across his face and he said, ‘When I leave the stage for good, I will be the most famous man in America.’”

Lincoln was carrying gently across the street to the home of William A. Petersen, where he was lain diagonally on a bed in a back bedroom.

Hysterical crowds filled the street as the two Marines made their way back to the barracks, which was already on full alert. The next morning, Collum anxiously scanned the morning newspaper, which was filled with news of the assassination. He noted that the secretary of war was requesting “all officers who had witnessed the assassination to report at the Department.”

As Collum made his way along Pennsylvania Avenue to the War Department, he noticed the buildings draped with black cloth and all the flags at half-staff. When interviewed by the assistant secretary of war, Collum related what he had witnessed, adding the comment that if he had the presence of mind and if he had been armed, he “could easily have shot Booth.”

Security was tight throughout the city. Collum doubled his Marine sentries and strengthened the guard at the Navy Yard. Cavalry patrols combed the surrounding area in search of Booth and his confederates. Two ironclads, USS Saugus and USS Montauk, were moored at the Navy Yard wharf awaiting the conspirators once they had been detained.

Lewis Powell was the first man arrested. He had attacked Seward, who was bedridden because of a carriage accident, at his home on Lafayette Square. Powell stabbed Seward, his son Augustus, a guard and a messenger, and bludgeoned Seward’s other son, Assistant Secretary of State Frederick Seward, into unconsciousness. A jaw splint saved Seward’s life and the others’ injuries, while bloody, were not life-threatening. Powell, who ran from the house screaming, “I’m mad,” was supposed to meet Herold outside, but the commotion scared Herold off, leaving Powell wandering the streets. He was arrested three days later at Mary Surratt’s boarding house. “He was brought at midnight to the Navy Yard in a closed carriage,” Collum recalled. The next one received was Atzerodt. After his capture in Maryland, he was confined on Montauk and shut in a windowless room. Atzerodt was eventually transferred to Saugus, where he was held with Powell and other suspected conspirators including Michael O’Laughlen, Samuel Arnold, Mary Surratt and Ford’s stagehand Ned Spangler.

At one point, Atzerodt asked the Marine sentry to call the officer in charge. When Captain Frank Munroe arrived at the cell, Atzerodt told him that he had refused Booth’s order to kill the vice president, despite Booth’s threat to blow out his brains if he didn’t comply. Munroe signed an affidavit spelling out details of the prisoner’s claims of innocence. Others detained for their alleged roles in the Lincoln assassination included John T. Ford, owner of Ford’s Theatre, John “Peanuts” Burroughs, an African-American boy who held Booth’s horse for him in the alley outside the theater, Mary Surratt’s brother, John Z. Jenkins, and Honora Fitzpatrick, a 15-year-old girl who boarded at Mary Surratt’s house.

Late on 26 April, the news spread that a pursuing cavalry patrol had cornered and killed Booth in a barn on Garrett’s farm near Bowling Green, Va. David Herold was taken prisoner; the next day he and Booth’s decomposing body were brought aboard Montauk and placed under Marine guard. No one was permitted to enter, “except with a pass signed jointly by the Secretaries of War and Navy,” Collum stated. Even Surgeon General Joseph K. Barnes and Dr. John May were stopped until Captain Munroe verified their orders. The two commenced the autopsy of the bloated and stinking body as it lay upon a “carpenter’s bench.”

The corpse was confirmed to be Booth’s by a scar on his neck and a “JWB” tattoo on the back of his left hand, according to two Marine guards, Privates Henry W. Landes and John Peddicord, who overheard the doctor say, “This is Booth.”

Despite the strict order against doing so, Peddicord decided to take a souvenir after the autopsy had been completed. Years later he admitted: “While the steward wiped the instruments…I picked up a scissors and cut from…the top of Booth’s head a lock of hair. General Barnes heard the grating of the scissors and turned sharply around, but I evaded him by attempting to drive some sailors back who had crowded too close out of curiosity.”

Following the autopsy, Booth’s body was taken by ship to the Old Penitentiary at the Washington Arsenal where it was buried in an unmarked plot. In 1869, Booth’s brother Edwin was granted permission to remove the body and in Collum’s words, “the dust of John Wilkes Booth reposes in the family lot in a Cemetery in Baltimore.”

Within days, the prisoners were removed to USS Key Port and transferred to the authority of the provost marshal. After a seven-week trial, the nine judges of the military tribunal rendered a verdict on July 5: Atzerodt, Herold, Payne and Mary Surratt were found guilty and sentenced to hang. Three others were given life imprisonment and one, a sentence of six years’ hard labor.

In 1872, Collum, now a captain, was made fleet Marine officer of the Asiatic Station. He wrote “The History of the United States Marine Corps” in 1890; it was given favorable reviews and was deemed to have “lasting value.” He continued to write various articles about Marine history, such as “The First Time Our Marines Went to Panama,” which gave his personal experiences during the expedition. Collum retired with the rank of major in Philadelphia in June 1897. He always will be known as the first uniformed historian of the Marine Corps.

Calling himself a “subordinate actor” in the historic events surrounding Lincoln’s assassination, Collum wrote his recollections “after a lapse of many years” and concluded, some important incidents may have been forgotten.”

Indeed some of what Collum recalled does conflict with other eyewitness accounts. “Nevertheless,” he said, “it was my great and sorrowful misfortune to have been an eyewitness of the greatest tragedy of modern times.”

“They Have Killed Papa Dead!”

While the Lincolns were attending the play at Ford’s Theatre, their 12-year-old son Tad was at Grover’s Theatre to see “Aladdin.” also known as “The Wonderful Lamp.” He was accompanied by Alphonso Dunn from the White House staff. As they were watching the play, someone suddenly came on the stage and announced that the President had been shot in Ford’s Theatre.

Dunn immediately took Tad back to the White House, where the young boy ran into the arms of the chief doorkeeper, Thomas Pendel. ‘Oh, Tom Pen! Tom Pen! They have killed Papa dead! They have killed Papa dead!”

Pendel, a 41 -year-old retired Marine and policeman, soothed the grieving child through the long night. With his tall, body and thick black beard, he bore a striking resemblance to the president.

Pendel had enlisted in the Marine Corps at the age of 20 in Philadelphia and soon after sailed in USS Ohioto Veracruz, Mexico. In 1862, he received an appointment in the Washington Metropolitan Police. From this position, he was selected to serve at the White House as guard and doorkeeper during the Lincoln administration. He continued to serve at the White House for 36 years.