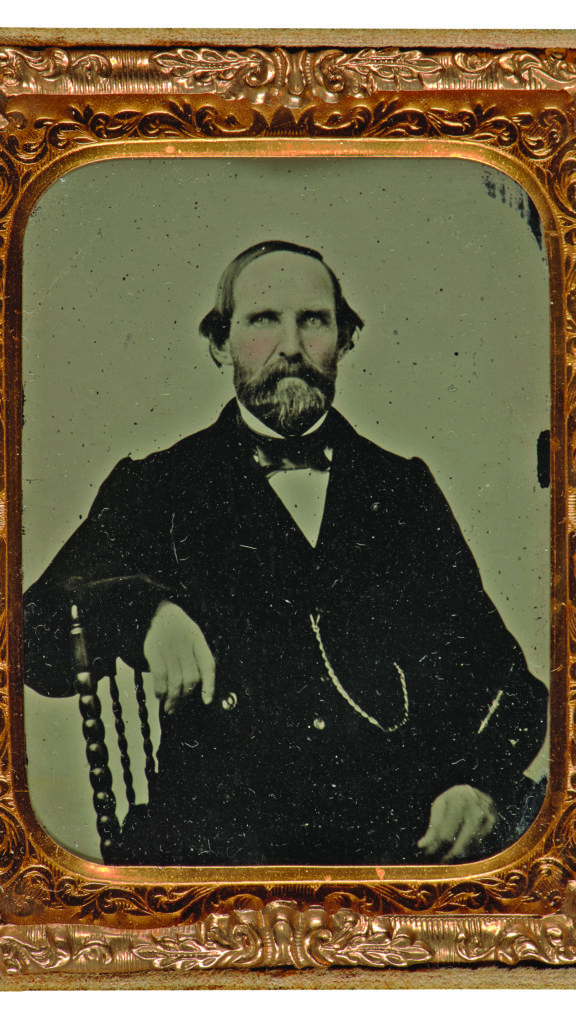

Flamboyant Texan Ben McCulloch was the best leader the Confederates had in Arkansas

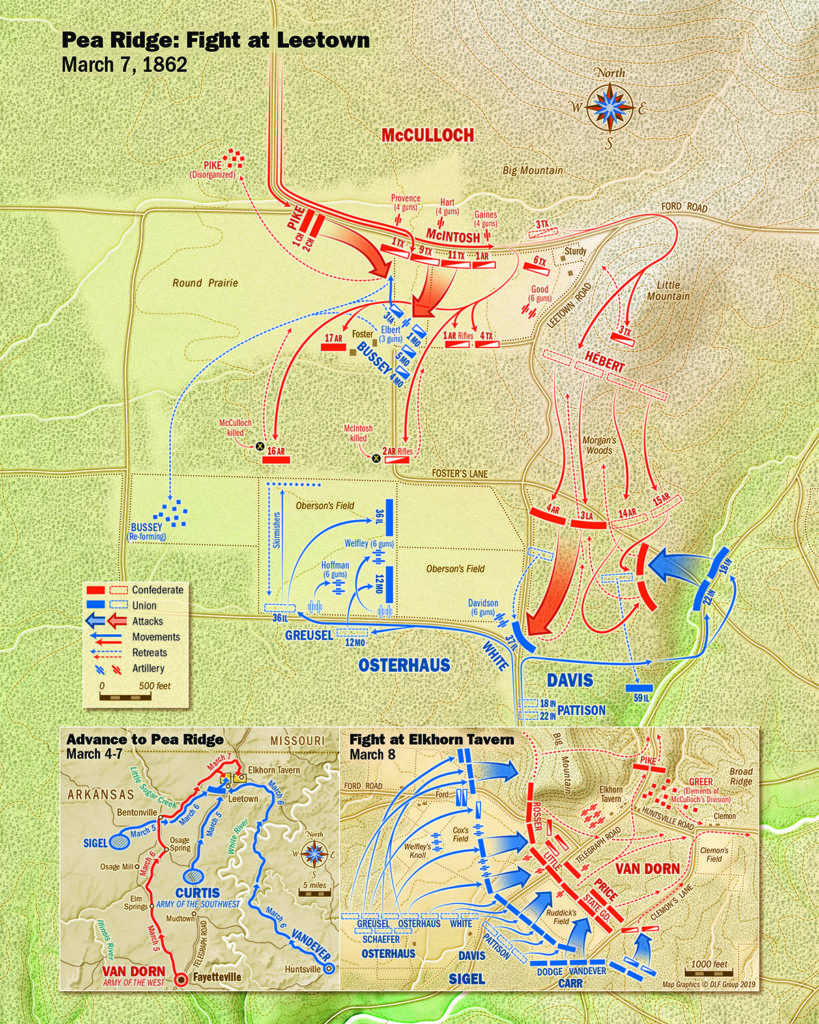

LATE IN THE MORNING of March 7, 1862, a Confederate column, exhausted from an overnight march, shambled along a narrow Arkansas road toward Elkhorn Tavern, a private home on Pea Ridge long used as a hostelry by travelers in the region. The Ozark winter added to their misery, numbing faces and freezing exposed fingers. Suddenly, from less than 200 yards away, Union artillery shells found their mark, obliterating a horse and sending its rider flying. Amid the shellfire, Brig. Gen. James M. McIntosh ordered his cavalry brigade to charge the enemy battery. With revolvers drawn and bugles blaring, hundreds of Confederate cavalrymen, including two Cherokee regiments under Brig. Gen. Albert Pike, wheeled right from the column and stormed across a barren wheat field. ¶ The charge overwhelmed the 1st Missouri Flying Artillery Battery, under Colonel Cyrus Bussey, as well as its cavalry escorts—the 3rd Iowa, 1st Missouri, and 5th Missouri. Wrote Henry Dysart of the 3rd Iowa: “In every direction, I could see my comrades falling. Men and horses ran in collision, crushing each other to the ground. Officers tried to rally their men, but order gave way to confusion.” Routed into the dense woods behind them, the blue-clad survivors abandoned the three-gun battery intact. ¶ Hoping to learn more about what was beyond those woods, Confederate Brig. Gen. Benjamin McCulloch ordered two companies from the 16th Arkansas Infantry forward as skirmishers. But the 50-year-old general—donned, as was his custom, in a black velvet suit and Wellington boots—also wanted to observe any Federal activity firsthand. “I will ride forward a little and reconnoiter the enemy’s position,” he instructed his staff. “You boys remain here. Your gray horses will attract the fire of the sharpshooters.” ¶ During his days on the frontier, McCulloch had been an accomplished scout; his subordinates seemed confident he’d suffer no harm. But within minutes of him riding through a maze of dried brush and meandering tree limbs, a rifle volley rang out and McCulloch was fatally hit. His death was a massive blow to Rebel hopes during the Battle of Pea Ridge (Elkhorn Tavern), and a significant setback for the South’s prospects in the Trans-Mississippi Theater.

Before the Civil War, Ben McCulloch was a true Texas legend. As an Austin newspaper editor once declared, he “has killed more bear than Davy Crockett, fought more Indians than Daniel Boone, and in [the war with] Mexico he was simply incomparable.” Born on November 11, 1811, in Rutherford County, Tenn., young McCulloch hungered for adventure. At age 24, he followed the famed frontiersman Crockett, a family friend, into Texas. Before reaching San Antonio, however, he came down with the measles, meaning he (fortunately?) missed a chance for martyrdom at the Alamo.

At the April 21, 1836, Battle of San Jacinto, in which Texas wrested its independence from Mexico, McCulloch fought as an artilleryman and then received a lieutenant’s commission for the stunning Texan victory. In 1846, the state legislature appointed him a major general in command of militia in western Texas. During the Mexican War, he led a company of Texas Rangers as a major and served as chief of scouts for Maj. Gen. Zachary Taylor, commander of the U.S. “Army of Occupation.”

Though outstanding as a frontier scout, McCulloch had no formal military training; rather, he was a self-taught tactician toughened by years in the saddle. “He was a thoroughly practical general,” wrote Sergeant William Watson of the 3rd Louisiana Infantry. “He gave much attention to the nature of the country in which he was going to operate in.” Frontier life had also led him to disdain military regalia. He adopted a less than martial appearance by preferring not to carry a sword and to wear his trademark black velvet suit.

In February 1862, not quite a year into the Civil War, Confederate forces in Missouri were in dire straits. State Guard troops under Brig. Gen. Sterling Price, the former governor, were in full retreat from Springfield. Although Price’s troops (with help from McCulloch’s Confederates) had won 1861 battles in Missouri at Wilson’s Creek and then, on their own, at Lexington, the makeshift army nevertheless operated on the fly—its ranks filled with poorly trained volunteers, many lacking adequate weapons.

When Union Brig. Gen. Samuel R. Curtis launched a late-winter offensive with a 10,500-strong force, it caught Price off-guard. “Pap” had little choice but to call on help from south of the Missouri-Arkansas border. Soon, McCulloch’s Confederate forces, consisting of Texas, Louisiana, Arkansas, and Indian Territory troops, were roused from their winter camps and called north. Unfortunately, mutual disdain between McCulloch and Price meant it wasn’t going to be a smooth process. McCulloch despised his fellow general’s politically inspired braggadocio and ill-disciplined troops, referring to them as Price’s “huckleberry cavalry.” Price, on the other hand, resented McCulloch’s generally condescending attitude. The two had not been on speaking terms for some time now.

After a meeting in Richmond with McCulloch on the Missouri situation, Confederate President Jefferson Davis agreed with the Texan’s assessment, calling Price “the vainest man I ever met,” but he also wasn’t about to hand the reins of the newly created District of the Trans-Mississippi to McCulloch—perhaps the best candidate but not a graduate of the U.S. Military Academy. Davis wanted a West Pointer. After being turned down by two other generals (one, Braxton Bragg, no less), he handed the shameless Mississippian Earl Van Dorn the position, to begin January 29, 1862.

Though known as an effective field commander, Van Dorn proved imprudent leading an army. He and his officers knew nothing about Arkansas, much less the troops defending it, and they had little regard for logistics. Further hampering the situation was an illness Van Dorn caught after falling into the freezing Little Red River on February 25. As a result, he had to be confined to an ambulance, inevitably incurring the ridicule of his men.

As Curtis’ Army of the Southwest proceeded across the Ozark Plateau toward Arkansas, Price’s and McCulloch’s forces were forced to retreat and regroup in the Boston Mountains, south of Fayetteville. Curtis was operating some distance from his main supply base at Rolla, back in Missouri, and, to his credit, Van Dorn saw an opportunity.

On March 2, Van Dorn reached Price’s camp, where he was treated to a gourmet breakfast of kidneys simmered in sherry (his last luxury meal for some time, it turned out). Two days later, the Confederate army—16,000 strong—began marching at a rigorous pace toward Curtis’ Federals in the vicinity of Bentonville—two so-called “German” divisions under Brig. Gen. Franz Sigel were west of Telegraph Road and two so-called “American” divisions, under Curtis, were to the east at Cross Hollows. A late-winter storm and snow-covered roads had made conditions wretched for both sides.

urtis learned from a spy of Van Dorn’s advance on March 5 and began moving north toward Elkhorn Tavern as Sigel’s Germans, at McKissick’s Creek, moved east. On March 6, Van Dorn’s men came close to catching Sigel’s rear guard at Bentonville, but the Federals managed to escape and regroup atop a bluff behind Little Sugar Creek.

Though his plans had been foiled, Van Dorn did not back down. He learned of a road running around the base of Big Mountain known as the Bentonville Detour that would take him to the rear of Curtis’ position. He ordered Price’s and McCulloch’s armies to proceed along the detour road.

For speed, Van Dorn mistakenly kept his supplies to a minimum—each man got rations for only three days, and tents and cooking utensils were left behind. Nevertheless, many fell from the ranks out of sheer exhaustion—beset by hunger, cold, and sleet. “Every half mile I saw infantry squads of fifty and sixty, and even more lying on the roadside, asleep, and overcome with hunger and fatigue,” wrote a Texas cavalry officer.

Local Unionists kept Curtis informed of Van Dorn’s progress. To slow the Confederate advance, Union Colonel Grenville M. Dodge had his regiments chop down trees along the Bentonville Detour, effectively blocking the road and costing Van Dorn precious hours clearing away the obstructions. More hours would be lost crossing Little Sugar Creek, as the men were forced to pick their way single file over a narrow footbridge made of logs.

Van Dorn, accompanying Price, had hoped to make a dawn attack on March 7, but the delays forced his hand. To save time, he made a fateful decision, ordering McCulloch—last in the marching order on the detour—to countermarch to Ford Road while Price continued marching. From Ford Road, McCulloch was to swing east and rejoin Price near Elkhorn Tavern, the Telegraph Road establishment so named for the pair of elk antlers affixed to its roof.

Because the Rebel army would now be divided in two, the playing field was at least leveled for Curtis’ outnumbered force. McCulloch remained confident, though, vowing to his officers after receiving the new orders, “We are going to take ’em on the other wing.”

Although Van Dorn was gaining Curtis’ rear, the delays had bought the Union commander critical time to take action. He prudently alternated his defensive lines from facing south to north. But as Colonel Peter J. Osterhaus marched toward the tiny farm hamlet of Leetown to secure the Union left, he was surprised to spot McCulloch’s entire division less than a mile away, marching east on Ford Road. He ordered the 36th Illinois, 12th Missouri, and 22nd Indiana infantry regiments, under Colonel Nicholas Greusel, to stay back and form a line at a barren cornfield known as Oberson’s Field. Osterhaus then accompanied Bussey’s 1st Missouri Flying Battery and the 3rd Iowa, 1st Missouri, and 5th Missouri Cavalry up Foster’s Lane.

After passing through a dense tree line, Bussey’s three-gun battery deployed to the right below a wheat field bordering Ford Road and opened fire on McCulloch, hoping to stall the Confederate march. Though caught off-guard, McCulloch’s cavalry responded by capturing the battery—with some of Albert Pike’s Cherokees even celebrating by taking the scalps of eight dead Union cavalrymen.

Tensions soared as a dozen riderless horses, some drenched in blood, poured out of the trees toward the Federal line. A sharp warning went out, “Look out for the cavalry!” Infantrymen deftly stepped aside to let the horses pass. Bussey’s routed troopers soon followed, shouting, “Turn back! Turn back! They’ll give you hell!” Unfazed, Greusel stood in his stirrups. “Officers and men, you have it in your power to make or prevent another [First] Bull Run affair,” he exhorted. “I want every man to stand to his post.” To help determine the Rebels’ next move, two companies of the 36th Illinois were sent forward as skirmishers. With rifles cocked and leveled along a wooden fence bordering the tree line, the skirmishers waited.

Fearful there might also be Union troops in his rear, McCulloch decided an immediate attack on Osterhaus’ position at Leetown was necessary. Advancing south through the tree line, he would personally command the 16th and 17th Arkansas Infantry, assisted by the 2nd Arkansas Mounted Rifles under General McIntosh. As detailed above, McCulloch decided prior to the attack to reconnoiter the Union position in Oberson’s Field himself.

McCulloch had instructed four Louisiana and Arkansas infantry regiments under Colonel Louis Hébert, on his left, to move through Morgan’s Woods and prepare for an assault. Gunfire from the direction of Oberson’s Field would provide the signal for Hébert to advance. The rest of McCulloch’s troops were held back at Ford Road to await further orders—orders that were never received.

After reaching Elkhorn Tavern the morning of March 7, Price attacked a hastily assembled Union line under Colonel Eugene A. Carr. Confederate numbers had a telling effect as the Rebels advanced south along Telegraph Road, slowly pushing Carr back from the tavern. Despite suffering with three wounds, Carr managed to hold on long enough to prevent a complete rout. Union supply wagons, in the path of the Confederate advance, were pulled back to a safe distance.

Later in the day, to Carr’s left, Union skirmishers nervously positioned behind a dense line of woods in antici-

pation of a Confederate onslaught. When a black-suited rider—McCulloch—suddenly emerged from the trees, an advance contingent of men from the 36th Illinois quickly fired a volley, then watched as the rider tumbled from his saddle. Hit by the volley as well, McCulloch’s terrified horse galloped from the scene. For nearly an hour, McCulloch’s men waited without hearing from their commander before advancing.

Though uncertain of how big a force was behind McCulloch, the Union skirmishers eventually let down their guard and begin looting the deceased general’s body. Private Peter Pelican rifled through McCulloch’s pockets, taking his pocket watch, and his mates lifted the general’s field glasses and carbine. Before they could finish their morbid endeavor, however, the Federals were forced to flee, as the 16th Arkansas closed in.

With a bullet through his heart, McCulloch had died before he hit the ground. His corpse was partially concealed in the brush, so the soldiers of the 16th Arkansas almost overlooked it. Horrified by the discovery, one gasped, “Oh my God! It’s poor old Ben.” Lieutenant Benjamin Pixley quickly covered McCulloch’s body with his coat.

Hoping to prevent any loss of morale, Pixley urged the others, “We must not let the men know that General McCulloch is killed.” But when McIntosh was informed of McCulloch’s death and assumed command, he unwisely stayed on the battlefield instead of pulling back behind the lines. Just like his predecessor, McIntosh was struck down, this time while leading a dismounted assault.

Command thus fell to Hébert, but the colonel was captured leading his infantrymen through Morgan’s Woods. Under intense shellfire, Hébert’s men became a disorganized mob in the smoke-filled woods. Wrote Sergeant Watson: “Suddenly, something like a tremendous peal of thunder opened all along our front, and a ridge of fire and smoke appeared close before us, and the trees round us and over our heads rattled bullets like a hail storm.”

With the arrival of Colonel Jefferson C. Davis’ troops, Osterhaus succeeded in fending off the attacks. The gray-clad men, stymied by the loss of their senior commanders, retreated in confusion back to Ford Road. Pike assumed command now, but the general—incompetent at best, and never fully briefed on Van Dorn’s battle plan—halted the attack on Leetown. He then led McCulloch’s troops up the Bentonville Detour to join Van Dorn and Price.

Fighting would continue the next day, but Van Dorn soon realized he had little choice but to withdraw from the field—he was on the receiving end of a massive artillery barrage and had no ammunition wagons within reach. In the words of William Baxter, a Fayetteville minister who witnessed the retreat: “And thus, for hours, the human tide swept by, a broken, drifting, disorganized mass, not an officer, that I could see, to give an order.”

Curtis’ losses in the battle were 1,384 killed, wounded, or missing/captured. Though his army suffered approximately 2,000 total casualties, Van Dorn tried to downplay the loss. “I was not defeated,” he claimed disingenuously, “…only foiled in my intentions.”

McCulloch’s black suit became his burial shroud. He was first buried on the battlefield, but reburied along with other Pea Ridge Confederate dead at a Little Rock cemetery before again being reinterred at the Texas State Cemetery in Austin. McCulloch’s death and the ensuing defeat at Pea Ridge profoundly affected the course of the war. Never again would the South have a better opportunity to secure Missouri for its cause and favorably turn the tide of the war in the Trans-Mississippi Theater.

McCulloch’s death was a tragic loss for the South; but he at least died heroically on the battlefield, unlike his two fellow senior officers at the battle. Van Dorn, the 42-year-old womanizer, was murdered by a jealous husband, George Peters, in Spring Hill, Tenn., on May 7, 1863. “Pap” Price served out the war, never achieving anything close to his early-war success at Wilson’s Creek. Notably, his autumn 1864 raid through Missouri—the South’s last major offensive in the West—was stopped at the October 23, 1864, Battle of Westport (again, the victor was his Pea Ridge nemesis, Curtis, by then a major general). Postwar, Price fled to Mexico, but while there apparently contracted “Montezuma’s revenge,” ignominiously dying of chronic diarrhea at age 58 in St. Louis on September 29, 1867.

McCulloch’s Union opponents, Curtis and Sigel, argued in public about who deserved full credit for the Pea Ridge victory. Although Curtis clearly was the Union force’s guiding hand in the battle, President Abraham Lincoln could not afford to alienate the politically valuable Sigel—a hero to German Americans, by far the single largest ethnic group in the Union Army during the war. Sigel was therefore “booted upstairs,” promoted to major general and transferred to the Eastern Theater, where he gained a well-

deserved reputation as an inept battlefield commander. After presiding over the Union defeat at the May 1864 Battle of New Market, Sigel was relieved of command. He died in New York City, at the age of 77, on August 21, 1902.

Of Pea Ridge’s principal commanders on both sides, Samuel Curtis achieved the most consistent and notable Civil War success. The West Pointer won the key battles of Pea Ridge and Westport, the latter engagement in 1864 helping him maintain firm Union control of Missouri, as had been the case for most of the war. Curtis did not survive the war long, however, dying in Council Bluffs, Iowa, the day after Christmas 1866—reportedly after a stroke. He was 61.

Donald L. Barnhart Jr., a frequent America’s Civil War contributor, is a volunteer at the Texas Civil War Museum in Fort Worth.

_____

Elkhorn Tavern Reopens to Visitors

Elkhorn Tavern reopened to the public on June 15, 2019. After extensive repairs to the floors, roof, and porch, visitors can now tour the famed tavern’s interior. Period furniture and park docents re-create the atmosphere of what the facility was like during the battle. Superintendent Kevin Eads and Supervisory Ranger Troy Banzhaf were presented a National Purple Heart designation—the country’s first national military park to receive this prestigious award.

The two-story tavern, featuring two chimneys, an overhanging roof, and a long front porch, was constructed as a residence in 1833.

Kentuckians Jesse and Polly Cox purchased the tavern in 1858, with Jesse realizing the opportunity the Telegraph Road offered. John Butterfield’s Overland Mail Company used the road as part of a stage coach route from St. Louis to San Francisco. Cox let travelers use their house for meals and overnight stays, and a nearby blacksmith shop provided replacement horses for the stage lines. The tavern’s name came from the elk antlers mounted on the roof, provided by a friendly neighbor.

In early 1862, sensing a coming battle, Jesse Cox left his family and drove his cattle to Doniphan County, Kan. On March 7 Polly, her daughter-in-law, two sons, and five slaves huddled in the tavern’s cellar as fighting broke out. The sound of gunfire, artillery, and the moans of the wounded could be distinctly heard. Some accounts claimed blood dripped from the floor above.

When the Cox family emerged from the cellar, they found the house a makeshift hospital and a yard littered with battlefield dead. Union officers ordered Polly and her family to leave, so they gathered the few belongings they could carry. Until burned to the ground by Confederate guerrillas the following year, Elkhorn Tavern was used as a Union headquarters. In 1959, the site was sold to the State of Arkansas and donated to the National Park Service. Between 1965 and 1967, the structure was restored to its appearance at the time of the battle.

According to Banzhaf: “It served as an army headquarters and a field hospital where the wounded from both sides received much needed medical attention. It was a landmark for those soldiers to come to in the years after the war. A place where they could come together in reunion, to reminisce, pay respects to the fallen and heal old wounds.” —D.L.B.

_____

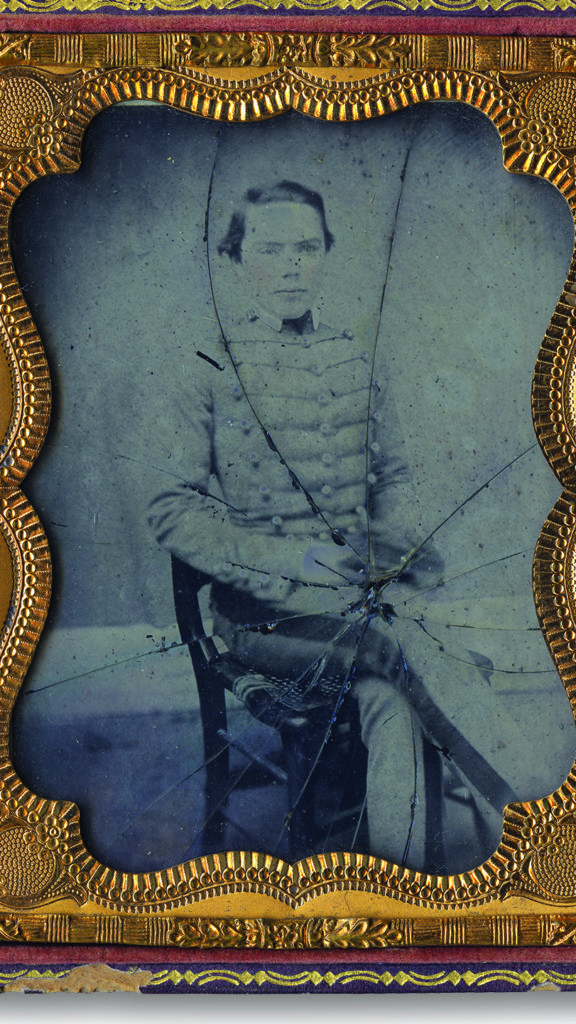

‘My God, Is My Boy Dead?’

Samuel Churchill Clark was the grandson of famed explorer William Clark and the son of noted designer-architect Meriwether Lewis Clark. Born in St. Louis in 1842, he entered West Point in 1859 but left the academy when the Civil War began and enlisted as a private in the Missouri State Guard. He first served with Clark’s Battery, 4th Division, Missouri State Guard, then as captain of the 2nd Light Battery (“Clark’s Artillery”) in the Army of the West. At Pea Ridge on March 8, the 19-year-old Clark was decapitated by a Union artillery round.

In his memoirs, Ephraim Anderson of the 1st Missouri Brigade wrote: “Clark, who at the time was fighting his battery, soon had all his pieces limbered up, remaining to see the last off safe, and was just in the act of leaving when a ball from the enemy’s cannon struck him, tearing off his head. His body was borne from the field by one of his lieutenants.”

“Thus perished this brave, gallant, and promising young officer—devotedly loved by his men—admired by all who had witnessed the coolness which characterized him in the hour of danger, and the skill and unfaltering courage always exhibited by him in the midst of conflict: though young in years, he was versed in the science of artillery warfare, and already distinguished in that important service.”

Major General Sterling Price (promoted March 6) was among Missourians in the Confederate ranks to mourn Clark, reportedly exclaiming when he heard: “My God, is my boy dead?” Clark is buried in Fairview Cemetery in Van Buren, Ark. —Melissa A. Winn