After sharing Nobel Prize, Ken Rutherford wrote a history of Civil War explosive devices

WHEN THE LANDMINE exploded under his Toyota Landcruiser, Ken Rutherford was temporarily blinded. Then he glanced on the floor of the vehicle and saw a dangling foot. It was his. Blood was everywhere. The date was December 16, 1993. The place: war-torn Somalia, where he was on a humanitarian mission on a brutally hot morning. Engaged to be married, Rutherford had no idea if he would live. He was 31 years old.

In shock, Rutherford somehow radioed for help. The pain was searing, unimaginable. The taste of his own blood was sickening. As he lay on the ground, he stared at a deep-blue sky. He wondered if it would be his last view on Earth.

Rutherford’s mind raced. He thought of Kim, his fiancée. Would he ever see her again? Airlifted to a hospital, he nearly bled to death. The former University of Colorado football player paid an awful price: His legs were amputated—the lower right leg in Kenya that day, the lower left in the United States in 1997.

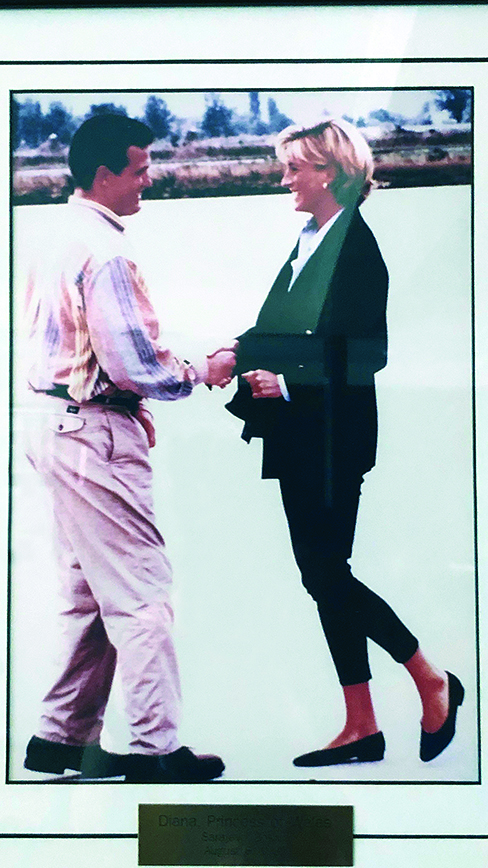

Since that life-altering day in Somalia, Rutherford, a 57-year-old political science professor at James Madison University in Harrisonburg, Va., has dedicated his life to the eradication of landmines worldwide. The Landmine Survivors Network, the organization he co-founded in 1996, even earned a champion in Princess Diana.

My initial connection with Ken Rutherford was a book: his. In 2018, I edited his America’s Buried History manuscript about Civil War landmines. His passion for the subject began in 2011, when he read a historical marker in Virginia that incorrectly stated landmines were first deployed during the war in 1864. The weapon was actually first used in 1862 during the Peninsula Campaign. Rutherford dug deep into the history of landmines. He traces their development from before the war through the establishment of the Confederacy’s Army Torpedo Bureau, the world’s first institution devoted to the systematic production of the notorious weapons.

“You’re a universe of one,” I told him during our first phone conversation. “No one else in the world has lost his legs and written such a book.”

The more I got to know Rutherford over the phone, the more I was determined to meet the Ph.D. who shared a Nobel Prize for his work to ban landmines, visited 106 countries…and lived much of his life without legs. On a sunny Saturday, Ken and I explored hallowed ground in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley. It was a remarkable eight-hour journey.

Gray clouds slowly give way to bright sunshine as Rutherford and I stop at an often-overlooked Valley site. On October 3, 1864, John Meigs, an Engineer Corps officer, was mapping routes near Harrisonburg for the movement of Philip Sheridan’s troops. The 23-year-old’s father was Montgomery Meigs, the well-regarded quartermaster general of the Union Army. A West Point graduate, John was a favorite of Sheridan’s.

About dusk on that raw, rainy Monday, Meigs’ group was approached on Swift Run Gap Road by three men on horseback. Were they Union soldiers? Rebel scouts? Guerrillas? Spies? During a confrontation, Meigs was killed by a soldier in the 4th Virginia Cavalry. A Federal soldier said he was shot in the back. Meigs was “murdered,” Sheridan wrote.

“For this atrocious act,” Sheridan noted in his report in reference to Meigs’ death, “all the houses within five miles were burned.” “The switch went off and this became total war,” says Rutherford of the ugly turn taken by Sheridan’s Valley Campaign.

“This,” the Shenandoah Valley Battlefields Foundation trustee adds as we examine the hillside where Meigs was killed, “is the most important site in the Shenandoah Valley.” Today, it’s bordered by a farm, railroad tracks, and massive silos. The approximate site of Meigs’ death is marked by a simple, gray granite marker. Soon, the immediate area, like much of the Valley, could be overtaken by 21st-century development.

Even wearing prosthetic legs, Rutherford navigates the hillside seemingly without significant strain. Most of us, thankfully, will never know what it’s like to live without legs. There’s a physical toll, starting with putting on the legs each day. A mental one, too.

As we contemplate 1864 while leaning against a farm fence, I gently steer the conversation to 1993.

“I had a chance to write my eulogy on that hard Somalia ground,” he tells me, “then I was given a second chance.”

Clearly, this man feels blessed to be alive.

“My heart,” Rutherford says, “blazes with gratitude.”

Much of the Shenandoah Valley near Harrisonburg is a crazy quilt of farm land and modern development. As we near Cross Keys battlefield and see rolling, open acreage, I roll down the window of Rutherford’s silver Suburban, hoping to breathe in one of my favorite smells: freshly manured fields.

In the past two decades, Rutherford has undergone 19 operations and received 20 blood transfusions. “My runway isn’t getting any longer for me,” he says. “…I don’t know how much longer I am going to make it.” And yet this man who has traveled the world has so much more to do.

“I want to raise bees, raise animals,” he says. His voice trails off.

“But I’ve run a good race.”

We stand on a ridge where Con-federate Brig. Gen. Richard Ewell deployed his artillery at Cross Keys on June 8, 1862. Now choked with vegetation, the view is not as open as it was the afternoon Yankees under General Robert Milroy unsuccessfully assaulted the heights under artillery fire. A 25th Ohio soldier remembered “the crushing of timber by the dread missiles mingled with the unearthly yells of opposing forces and the dying and screams of the wounded.”

Given what he experienced in Somalia, I wonder if Rutherford can relate to the suffering that occurred at Cross Keys.

“These guys,” he says, “had so much more to sacrifice than me.”

In nearby Port Republic, Civil War history jumps up at us at nearly every turn. With Union troops in hot pursuit “Stonewall” Jackson galloped down Main Street on “Little Sorrel” and across a covered bridge spanning the North River on June 8, 1862. Despite Union artillery crashing into its timbers, Jackson reached the relative safety of the opposite shore. Jackson escaped and whipped the Federals at Port Republic the next day.

Rutherford points out the site of the long-gone bridge used by Jackson. Then, a short distance away in the village, we visit the temporary resting place of the “Knight of the Valley.” On June 6, 1862, 33-year-old Brig. Gen. Turner Ashby was killed by a bullet through the chest on the outskirts of Harrisonburg. His body was taken to Frank Kemper’s house in Port Republic, where mourners, including Jackson, paid their respects. Ashby was propped up in a chair there and photographed by an unknown photographer.

Behind a chain-link fence outside a nearby mom-and-pop store, 62-year-old Jeff Coffman sweats in front of a smoker packed with chicken. On a table behind “The Barbecue King” rests his not-so-secret ingredients: a massive jar of vinegar, seasoning, lemon juice, pepper, and who knows what else.

Coffman tells us of a windstorm that toppled an ancient tree near his house several years ago. Under that white oak, according to local legend, Stonewall held a Sunday service in mid-June 1862. In 2007, trimmings from the “Jackson Prayer Tree” were used to create pens.

At Piedmont, perhaps the least spoiled battlefield in the Valley, Rutherford and I admire an awe-inspiring scene: to our left, the Appalachian Mountains; to our right, Massanutten Mountain and the Blue Ridge. In an untilled field of wildflowers, Confederate General William “Grumble” Jones was killed instantly by a bullet to the head on June 5, 1864.

Hours later, Rutherford and I stand in a seldom-visited Cross Keys field on the old Widow Pence farm, where soldiers in the 548-man 8th New York—mostly Germans and Hungarians—suffered nearly 50 percent casualties. “The dead and wounded Yankees,” a Georgia soldier wrote, “was lying on the field as thick as black birds.”

Rutherford poses for a photograph, the beautiful, massive Massanutten Mountain looming over his right shoulder. Surely his family must be proud of this man who has achieved so much. Remember Kim, his fiancée? They were married in 1994. The couple has five children.

I think about what Rutherford told me hours earlier: “I am grateful every single day I’m above ground.”

And so our 100-mile journey in the Valley is complete. I learned so much—about perseverance, courage, tenacity, gratitude.

I learned a lot about the soldiers who fought here, too.

John Banks is the author of the popular John Banks’ Civil War blog. He lives in Nashville, Tenn.

This story appeared in the December 2019 issue of Civil War Times.