The obsolescent fighter entered Soviet service in 1953

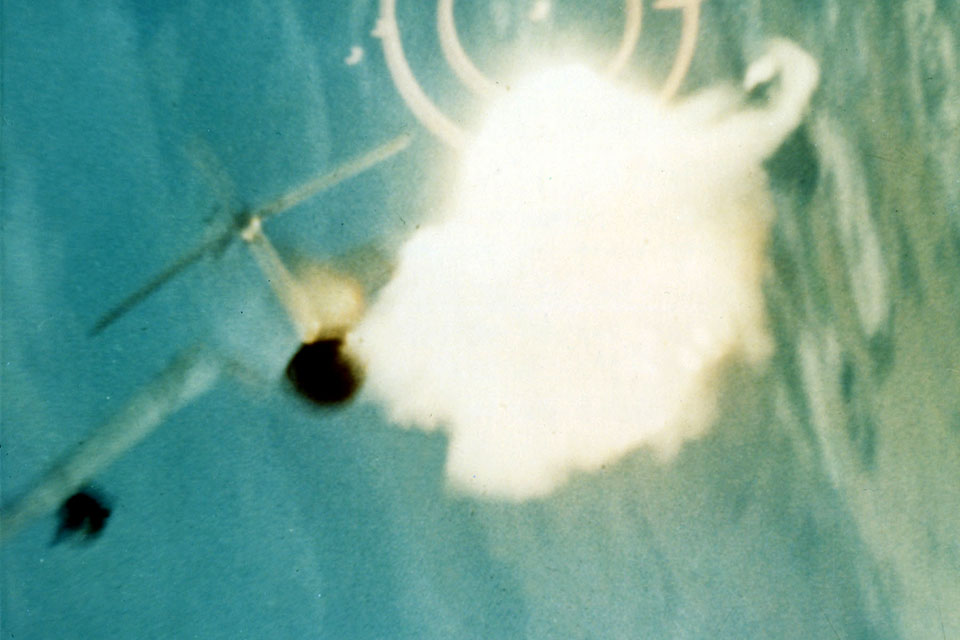

No one saw the two low-flying North Vietnamese MiG-17 fighters approaching the large force of U.S. Navy and Air Force aircraft, which was zeroing in on taking out the North’s Than Hoa Bridge on April 3, 1965. Visibility was good at high altitude, but hazy below 5,000 feet. Flying at about 1,000 feet, the MiG-17s closed in on a pair of F-8E fighter-bombers that had just pulled up from bombing the bridge. When the range closed to about 700 feet, Lieutenant Pham Ngoc Lan opened fire, scoring several 23mm cannon hits. One F-8 appeared to explode as it dropped away, and Pham’s wingman, Lieutenant Phan Van Tuc, opened fire on the second F-8. While the North claimed two victories that day, neither F-8 was actually shot down. However, the engagement did mark North Vietnam’s first MiG-17 intercept in what would become the longest air war in American military history. The next day would see two confirmed shoot downs of F105s by MiG-17s.

Although U.S. intelligence was aware of the MiG-17’s presence in North Vietnam several months earlier, the fighter’s April exploits came as a tactical surprise. Most analysts had expected North Vietnam’s pilots to continue training for another year before seeking engagement. After all, they were outnumbered and equipped with a clearly inferior fighter aircraft, and they lacked the Americans’ high level of training. Intelligence, however, had misjudged North Vietnam’s mindset and culture. Moreover, American rules of engagement gave the aerial initiative to the North Vietnamese. In 1965 American forces were prohibited from attacking North Vietnam’s fighter airfields, allowing its pilots to train, rest and launch at times of their choosing. Equally important, as American radar coverage did not reach those airfields, the fighters’ takeoffs went undetected. Those technological and tactical challenges to the United States would be overcome in the intervening years, but in the meantime the North Vietnamese came to understand and exploit both U.S. operating patterns and rules of engagement.

The Vietnam People’s Air Force (VPAF) was introduced to the MiG-17 (which carried the NATO designation Fresco) in October 1960, when 57 of its pilots were dispatched to China’s Son Dong Air Base for conversion training. Another handful of pilots went to Russia to train. Essentially an evolutionary improvement on the Korean War’s MiG-15, the MiG-17 was a subsonic, swept-wing fighter aircraft that entered Soviet service in 1953. The MiG-17F production variant constituted the bulk of those provided North Vietnam. Its Klimov VK-1 afterburning jet engine provided a maximum thrust of 5,900 pounds, giving the plane a thrust-to-weight ratio of .45 to 1 and a top speed of Mach .97 at 15,000 feet in a clean configuration (no drop tanks or bombs).

Although the Fresco was capable of carrying bombs, American pilots most often saw it in an air-to-air configuration with one or two external fuel tanks, which were dropped upon entering an engagement. The MiG-17F had no radar and was not equipped to carry air-to-air missiles. The late-model MiG-17PF carried an SRD-3 gun-ranging radar and SIV-52 infrared sight, a combination that suited a night fighter. All MiG-17s’ armament consisted of one N-37D 37mm cannon with 40 rounds, and two NR-23 23mm cannon with 80 rounds per gun. Neither weapon was fast-firing, since the fighter had been developed to engage strategic bombers. The ammunition load limited the pilot to about seven seconds of firing, significantly less than the American F-100, F-105 and F-8. The plane had a tactical radius of 210 nautical miles and a service ceiling of approximately 47,000 feet.

The MiG-17’s lack of hydraulic control systems made it an exhausting and difficult plane to maneuver over an extended engagement. High-speed maneuvers at low altitude were particularly taxing for the pilots. Its light weight, however, made it extremely maneuverable at low speeds. That was to prove its most useful characteristic in the aerial engagements over North Vietnam. The VPAF’s tactics were designed to exploit the Fresco’s strengths while masking or compensating for its weaknesses, which included an inferior acceleration rate and poor sustained turning rate at low altitude.

The first 36 MiG-17Fs entered North Vietnamese service with the 921st “Sao Do” Fighter Regiment on February 3, 1964. The pilots returned to Vietnam from China on August 6 and began an intense training program out of Noi Bai Airfield. In addition to longer flying hours, they also spent hours in ad hoc simulators, studying U.S. aircraft silhouettes and receiving instructions on U.S. attack and fighter tactics from Soviet air force and Vietnamese intelligence officers.

The VPAF assessed two key weaknesses in early American air operations. First, the aircraft flew in large groups along fixed routes. Second, the bombers had few if any fighter escorts. Most U.S. aircraft came in below 1,000 feet. The Vietnamese pilots, therefore, practiced air combat maneuvering and other flight operations at those altitudes. The North Vietnamese also noticed that American night attacks lacked fighter escorts, so they requested a night fighter version. The Soviet Union delivered a dozen PF variants in 1965. Finally, noticing areas of North Vietnam where the U.S. planes didn’t go, the VPAF decided to launch intercepts from those areas and conduct the aerial equivalent of “hit and run” strikes against the American strike packages.

Technology and the Fresco’s flight characteristics favored that approach. In those days before “look down/shoot down” radars, terrain features interfered with the American aircraft radar’s ability to detect targets operating close to the ground. The first Airborne Early Warning (AEW) aircraft lacked the computerized signal-processing capabilities characteristic of today’s Airborne Warning and Control System aircraft. So even when the AEW aircraft were deployed in support of U.S. strike packages, they were of limited value until the MiGs rose above 2,500 feet. Moreover, the Fresco’s jet engine emitted no smoke, making the much smaller and lighter Soviet-built aircraft very difficult to spot visually.

Below 5,000 feet, the MiG-17 enjoyed a much better roll and initial turning rate than all of its American counterparts except the F-8E. Below 200 knots, it also had a better initial climb and sustained turning rate than the F-4 and F-105, regardless of altitude. All U.S. jet aircraft, however, had far superior speed, acceleration and sustained climb rates than the MiG-17. Below 20,000 feet, the F-4’s sustained turning rate was superior to the Fresco’s if the pilot kept his air speed above 400 knots. Above 20,000 feet, the Fresco’s initial and sustained turn rates were better than all U.S. aircraft except the F-8E, regardless of air speed. The MiG-17 may have been designed as an interceptor, but over North Vietnam, where guns and aircraft agility had the advantage, it was employed as a close-in dogfighter.

The early F-4 Phantom’s lack of cannon put that highly capable aircraft at a disadvantage against such tactics. American air-to-air missiles had been designed to engage large bombers, and therefore had difficulty taking down a highly maneuverable fighter aircraft. Of the three missiles in service during the Vietnam War, the infrared guided AIM-9 Sidewinder was the most effective. Simple and efficient, it locked onto the enemy jet’s exhaust gases, provided the American pilot got almost directly behind his opponent and fired from within two nautical miles.

Technically, the AIM-7 Sparrow should have been more effective. Its radar guidance enabled the American aircraft to engage the enemy whether he was behind or in front of it. More important, the MiG-17 had no radar warning or countermeasures systems. The American pilot, however, had to keep the enemy aircraft within his fighter-radar’s guidance beam throughout the engagement. If the Fresco pilot spotted a Sparrow launch in time, he could evade the missile by a tight, rapidly descending turn. Another problem was that the Sparrow’s greater complexity gave it a higher failure rate than the Sidewinder.

The rules of engagement represented a further disadvantage for the Americans. The U.S. forces were prohibited from conducting preemptive strikes against North Vietnam’s fighter airfields. While Robert McNamara was secretary of defense, U.S. forces were only allowed to conduct retaliatory strikes against airfields from which the North Vietnamese launched intercepts against U.S. air strikes. The approval process required military planners to prove that the intercepts came from the airfields they wanted to strike. In addition, the rules prohibited engagement of any aircraft without visual confirmation of its identity and threat. Although this rule was prudent (it significantly reduced the possibility of engaging friendly aircraft), it gave the VPAF the initiative and ensured a close-in engagement, which favored the North’s aircraft.

Despite those challenges, both the U.S. Navy and Air Force quickly developed tactics to counter the MiG-17s. The key was to use the American aircraft’s superior engine power and climb capabilities to conduct fight-in-flight regimens that favored American aircraft strengths. The MiG-17s could not keep up with an American fighter that accelerated away. One technique was to use deceptive fighter packages as if they were strike packages in an effort to induce an intercept.

What followed was a cat-and-mouse game, wherein the Vietnamese tried to engage only those aircraft that seemed to be or should have been low on fuel. Their GCI advised pilots on the locations of American pilots who had just reported “bingo.” In a fashion similar to British Harrier engagements against Argentine A-4s making bomb runs at maximum range in the Falklands War, the Vietnamese fighters would try to intercept an American aircraft before it reached the relative safety of the combat air patrols supporting their raids. An American flying short on fuel couldn’t employ his aircraft’s superior speed to advantage for fear of running out.

By 1966, American fighter pilots had all but mastered Fresco. By 1969, the MiG-17 was relegated primarily to a training and supporting intercept attack role. Two years later, VPAF leaders decided to shift some of their MiG-17s to a surface attack role, with 250-kilogram bombs replacing the two 400-liter drop tanks it carried for air intercept missions. Air-to-ground attack training began in March 1971. The initial focus was on antishipping missions. Cuban instructors taught maritime strike tactics, while North Vietnamese intelligence studied U.S. naval operating patterns off the North’s coastline.

In March 1972, the 923rd Fighter Regiment’s first six pilots graduated from the training program. They staged to Gat Airfield on April 18, 1972, and awaited their opportunity. It came at 1605 hours the next day, when two Frescos launched to strike four U.S. warships operating nine nautical miles from Nhat Le. The 402nd Radar Company provided target location and movement information as the flight flew just above the terrain en route to the coast. The lead pilot, Le Xuan Di, spotted the smoke from one of the ship’s stacks before he crossed the coast.

A pair of motor torpedo boats was also moving in to strike the U.S. Navy task element as Le approached the target area. He reported sighting a U.S. warship and was given the attack order. He estimated the ship, a World War II–era destroyer, to be 10 to 12 kilometers away as he accelerated toward it. It turned out to be USS Higbee. The other Fresco, piloted by Nguyen Van Bay, went after the second group of ships about five nautical miles away, the guided missile cruiser Oklahoma City and the destroyer Sterrett.

Le climbed to about 400 meters for his approach and released his two bombs from a shallow dive. (Higbee’s captain says the Fresco conducted two attacks, dropping one bomb each time. Le says he flew straight to the target, dropping both bombs at the same time in a single attack.) One bomb hit and destroyed Higbee’s rear gun mount, while the other missed the ship’s fantail by about 10 meters. Le pulled away to the left, did a slow descent to 100 meters and returned directly to Gat. Nguyen overshot Oklahoma City and had to come around for a reattack. He released his bombs too early, missing the cruiser by more than 50 meters and inflicting little noticeable damage. Sterrett fired a Terrier surface-to-air missile at Nguyen as he pulled away, and Sterrett’s crew claimed to have shot him down. The North Vietnamese, however, admit no aerial losses in the attack. To add to the confusion, the North Vietnamese shore batteries spotted Sterrett’s missile launch shortly after the bomb splashes and reported that it was also damaged in the attack. In fact, Sterrett suffered no damage at all. The entire engagement took less than 17 minutes.

Some defense commentators have claimed that Frescos were used for ground support during North Vietnam’s final offensive in 1975, but that has never been confirmed. They were employed with some success, however, against Chinese ground forces during the brief Sino-Vietnamese border conflict in 1979. North Vietnam accepted delivery of some 90 MiG-17s during the Vietnam War, and about 30 of them reportedly remained in service as of 1980. The last MiG-17s were retired from service shortly thereafter.

Although the MiG-17 wasn’t the best fighter to serve North Vietnam during the Indochina War, it was that country’s first jet fighter and its first interceptor capable of engaging U.S. high-performance aircraft. Its historical importance in Hanoi is best illustrated by the fact that present-day Vietnam commemorates the day of its first claimed aerial victories, April 3, 1965, as Air Force Day. The Fresco’s impact on the United States was both operational and technological. The MiG-17’s introduction into the battle forced the U.S. military to change its aerial tactics and operations to an extent that far exceeded what one would expect in countering such a small group of obsolescent fighters. Much of that was because of the limitations the Americans placed on their operating forces; but some of it was also the result of overconfidence in the capabilities of their air-to-air missiles systems.

Interestingly, every American fighter aircraft introduced into service since 1965 has been equipped with cannons for close-in air-to-air engagements. Viewed in that context, perhaps the MiG-17 could be seen as the Vietnam-era fighter that most affected U.S. postwar fighter designs.

Originally published in the June 2007 issue of Vietnam Magazine. To subscribe, click here.