Writing Wyatt

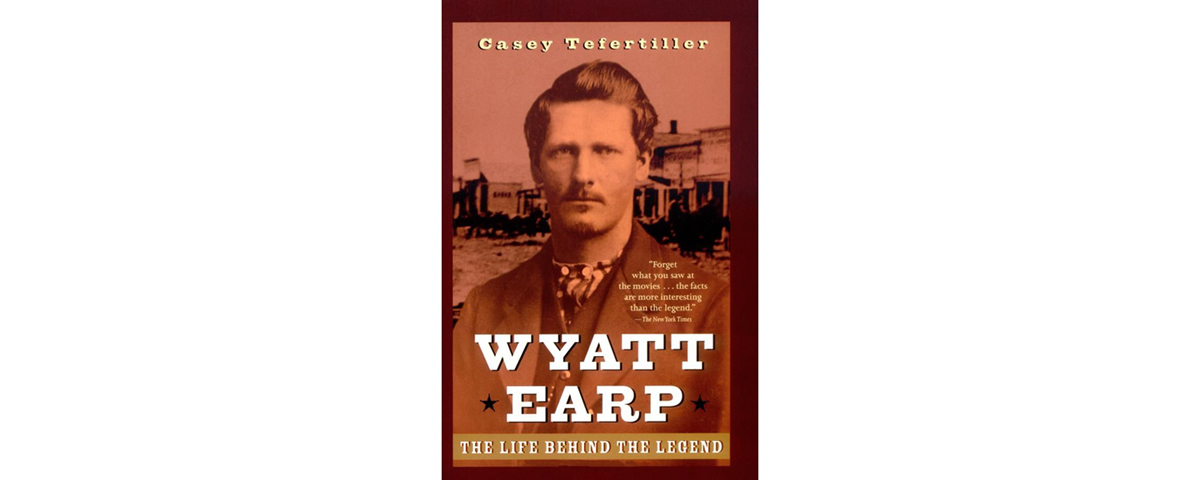

Hard for this old editor to believe, but it was 20 years ago Casey Tefertiller’s biography Wyatt Earp: The Life Behind the Legend came out like a Vendetta Ride—shooting down many of the divisive Earp fictions promulgated through the years and exacting revenge on self-proclaimed Earp authority Glenn Boyer by disregarding everything he had ever written on the subject. The late California author Jack Burrows called Tefertiller’s tome “the book to end all Earp books—the most complete and most meticulously researched.” Boyer naturally disagreed, commenting, “Writing about Earp and failing to mention me and my work is something like writing about Catholicism and neglecting to mention the Pope.” In an interview in the October 1998 Wild West Tefertiller explained his reason for not referencing any of Boyer’s works:

It was a great disappointment to realize that Glenn Boyer’s material was not honest, accurate and truthful.…He says he should be believed just because he says so. The problem is he has a very poor record with the truth.…It is important that people writing on historical subjects not blindly follow what has come before. In that regard Glenn Boyer has taught historians a valuable lesson.

When writing The Life Behind the Legend, Tefertiller certainly did not blindly follow what had come before—notably Stuart Lake’s 1931 mythmaking hagiography Wyatt Earp: Frontier Marshal, in which Earp comes across as a heroic defender of law and order; Frank Waters’ critical 1960 book The Earp Brothers of Tombstone: The Story of Mrs. Virgil Earp, a litany of Wyatt’s faults and old-timers’ criticisms of him; as well as such Boyer offerings as I Married Wyatt Earp: The Recollections of Josephine Sarah Marcus Earp (1976) and Wyatt Earp’s Tombstone Vendetta (1993), both of which have, to say the least, major factual issues. Gary L. Roberts, who later penned a biography of Earp pal Doc Holliday, wrote in 1998 that Lake (who died in 1964), Waters (who died in 1995) and Boyer (who died in 2013) did significant research and “each had access to a principal figure in the Earp story,” but that “all three were disappointed in what they received from the participants, and all filled in the gaps by putting words in the participants’ mouths.”

As Tefertiller puts it in our October cover story, “The initial public perception of Earp had been fashioned on frauds and fantasies.” The longtime San Francisco newspaperman took three years to write his 1997 biography, as he was fascinated by the dichotomy of the divergent legacies and wanted to use primary sources to get at the truth about Wyatt. For many of us drawn to the Earp story, he un-muddied the waters, but it is also clear he didn’t produce “the book to end all Earp books.” Since publication of The Life Behind the Legend other honest researchers have made exciting new inroads on the subject. “The discoveries have been exhilarating,” Terfertiller agrees, “some changing the way we view the subject.” In our cover story he looks at some of those discoveries, including one the late Roger Jay presented in the August 2003 Wild West—that at a time when, according to Stuart Lake, Wyatt was hunting buffalo on the Plains, the future “Lion of Tombstone” was actually working in brothels in and around Peoria. Ill.

Tefertiller welcomes any new documented information presenting a more accurate picture of a famous Westerner who was neither a knight in shining armor nor a knight in a black Stetson. “It is without question,” he insists, “the most exciting time in Earp studies since the guns went off in the streets of Tombstone.” WW

Wild West editor Gregory Lalire wrote the 2014 historical novel Captured: From the Frontier Diary of Infant Danny Duly. His article about baseball in the frontier West won a 2015 Stirrup Award for best article in Roundup, the membership magazine of Western Writers of America.