Flood & Drought—No Doubt

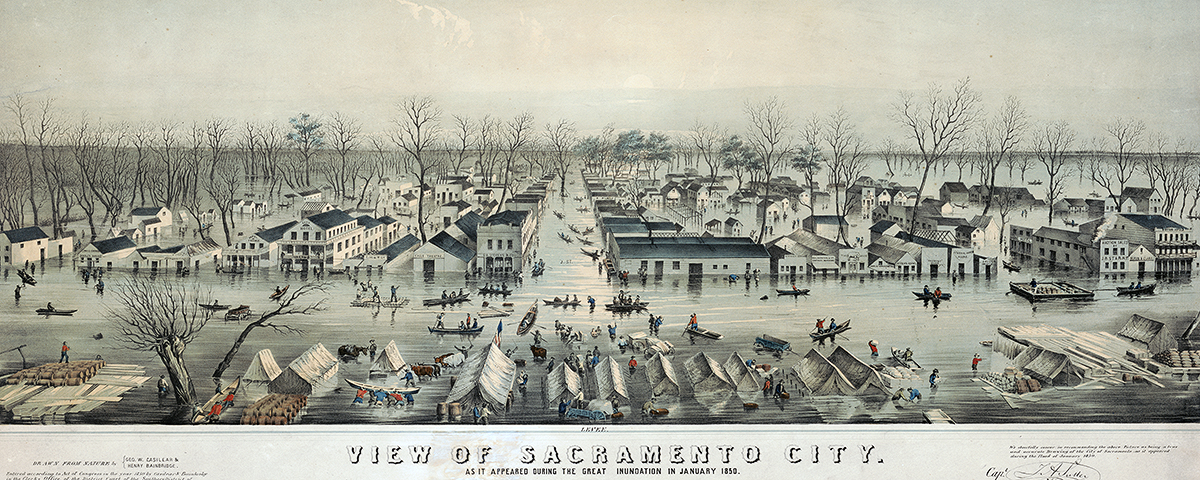

While we—Californians or not—wait for the big one, perhaps we should consider the possibility the big one will be something other than an earthquake, namely a megastorm with the kind of massive flooding not seen by man or beast since 1862. That last great flood, which actually began in November 1861, was the result of Pacific storms that swamped the Golden State faster than the Forty-Niners had a dozen years earlier (see cover of a California Gold Rush pamphlet at right). The Sacramento Valley turned into an inland sea, a vast lake formed south of Los Angeles and large brown ponds even appeared on the Mojave Desert. On Jan. 10, 1862, Governor-elect Leland Stanford traveled by rowboat from his Sacramento mansion to the inauguration site, and 12 days later the state Legislature moved from Sacramento to San Francisco to wait out the floods. There was no official death toll, but as Chuck Lyons writes in this issue, “By the time the waters receded, thousands of people—as well as countless cattle, horses and other domestic animals—lay dead.”

Several years ago a two-year study by the U.S. Geological Survey concluded California was at risk of another catastrophic winter storm. Even though drought conditions have prevailed in the state for much of the 21st century, and the current drought shows no sign of letting up, history suggests a hard rain will fall…eventually. Alternating flood and drought cycles are par for the course in California. Lyons notes that for at least two decades prior to the great flood of 1861–62 drought bedeviled the region: “Lakes dwindled, their shorelines showing where water had once lapped. Rivers and creeks fell. The very earth cracked.” The drought even threatened to dry up miners’ pay dirt. The stage was set for a disastrous deluge. Scores of Californians drowned, and up in the mining camps floodwaters rendered roads impassable. “The long interruption of travel and the impossibility of transporting supplies had created a famine in the mines,” recalled one 19th-century historian of the great flood. “Gold was plentiful, but food was scarce.”

Too much rain and too many swollen rivers in California accounted for the flooding—the miners and everyone else knew that. What they didn’t know about were “atmospheric rivers,” jets of warm moist air that originated over the North Pacific and transported enough water vapor to drown cats and cows in California. “We know,” writes Lyons, “that the Pacific’s atmospheric rivers are still forming and still sliding toward the California coast.” USGS scientist Lucy Jones certainly knows. She says another megastorm has the same probability as a major earthquake and “is potentially up to five times more damaging.” I don’t want to be an alarmist, but I hope Governor Jerry Brown can borrow a rowboat. WW

Wild West editor Gregory Lalire wrote the 2014 historical novel Captured: From the Frontier Diary of Infant Danny Duly. His article about baseball in the frontier West won a 2015 Stirrup Award for best article in Roundup, the membership magazine of Western Writers of America.