John Huston entered the U.S. Army in 1942 with distinctive credentials. In the previous two years, he had directed three hit films, including The Maltese Falcon starring Humphrey Bogart, which garnered an Academy Award nomination for Huston’s adapted screenplay. The army put his cinematic talents to good use. Major Huston filmed two ambitious documentaries for the Army Signal Corps in the next three years—one on army life in the Aleutian Islands, the other about the fighting near San Pietro, Italy.

Now, he had a new assignment. As the war in Europe wound down and American forces approached the Japanese home islands, the army wanted to document the medical treatment of battle fatigue casualties evacuated back to the United States. Because the condition—an acute nervous reaction to the stresses of combat—had received little publicity during the war, the army feared that those affected would be “misunderstood, mistreated, and looked upon with suspicion” when they were discharged into the civilian workforce. It wanted to reassure the public, especially employers, that those former servicemen were not dangerous and could function as well as the next man.

Huston had filmed the bitter fighting in Italy at perilously close range and understood what battle-fatigued soldiers were going through. “For months I had been living in a dead man’s world,” he said. This was true even after he returned home on leave: “Emotionally I was still in Italy in a combat zone.”

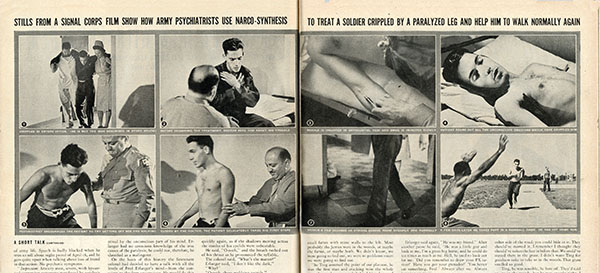

In spring 1945, Huston and a crew of six cameramen, six electricians, and two soundmen began filming at Mason General Hospital, an army psychiatric facility near Brentwood, New York, following a group of 75 combat veterans, all suffering from battle fatigue, as they went through an eight-week treatment program. Huston kept the cameras running continuously throughout treatment sessions to ensure he captured “the extraordinary and completely unpredictable exchanges that sometimes occurred,” he said. He shot more than 375,000 feet of film—nearly 70 hours—for a documentary that would run less than an hour. The soldiers took the filming in good spirits, posting a sign in their ward that read: “Hollywood and Vine.”

When the men first entered the program, many showed obvious signs of distress. Some had nervous tics; others had amnesia. Some were immobile; others stuttered so badly they could not communicate. The images Huston captured were jarring. He explained that “to see a psyche torn asunder is more frightening than to see people who have physical wounds.”

The film’s message was that these were normal men who had cracked under the abnormal stress of combat. “Every man has his breaking point,” explained narrator Walter Huston, John’s father. “And these, in the fulfillment of their duties as soldiers, were forced beyond the limit of human endurance.” As an army psychiatrist told the men, “If a civilian, the average civilian, were subjected to similar stresses, he undoubtedly would have developed the same type of nervous conditions that most of you fellows developed.” They had nothing to hide and nothing to be ashamed of, he assured them.

John Huston was impressed with the treatment the men received. “To me it was an extraordinary experience, almost a religious experience,” he said, “to see men who couldn’t speak, or remember anything at the beginning of their treatment, emerge at the end, not completely cured, it is true, but restored to the shape that they were in when they entered the army.”

Huston spent several months editing the film, which had the working title Returning Soldier—The Psychoneurotic and was eventually renamed Let There Be Light, and hand-delivered the finished product to Washington, D.C., in February 1946. He was proud of the result, later calling it “the most hopeful and optimistic and even joyous thing I ever had a hand in.”

Army brass were set to preview the film next, with a public premiere to follow in April at the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan. But the premiere never happened—for reasons that remain murky and may have had as much to do with stigma surrounding battle fatigue as with the revealing nature of Huston’s film.

Battle fatigue—now called posttraumatic stress disorder—emerged as the most unexpected and difficult medical problem of the war. It blindsided the military and threatened to become an epidemic that drained desperately needed manpower by immobilizing physically healthy soldiers, sailors, and Marines. Doctors quickly came to understand that battle fatigue was as much an injury as a gunshot wound, but old-school officers wrote it off as cowardice. Caught in the middle were the millions of servicemen—all potential victims who feared the condition as a reflection on their strength, dedication, and courage.

Let There Be Light illuminated that troubling issue. Battle fatigue, then called “shell shock,” had been a major problem for the Allies in World War I. It was widely reported among British and French troops who had been in combat for four years. And although American doughboys saw hard fighting for less than a year, nearly 12,000 of them were hospitalized for psychiatric reasons.

In 1940-41, as the United States mobilized for another war, military psychiatrists believed that men with preexisting mental illness were the ones who would later break down. Hoping to remove men they considered vulnerable to battle fatigue, psychiatrists rejected recruits at a rate 15 times greater than they had in World War I.

Despite those efforts, the tough fighting in early American campaigns produced an unexpectedly high incidence of battle fatigue among the troops. Navy doctor Lieutenant Commander Edwin R. Smith, who treated Marines evacuated from Guadalcanal, told Time magazine that conditions on the island had produced a “disturbance of the whole organism, a disorder of thinking and living, of even wanting to live.” Common symptoms were headaches, sensitivity to sharp noises, amnesia, panic, tense muscles, tremors, uncontrollably shaking hands, and weepiness.

As the fighting intensified, the number of battle fatigue casualties increased dramatically. Psychiatric admissions to army hospitals jumped from 114,055 in 1942 to 341,087 in 1943 and to 367,815 in 1944. Army discharges for mental health reasons went from 27,086 in 1942 to 140,723 in 1943 and 100,789 in 1944.

Battle fatigue was not limited to those new to combat. Author William Manchester, a Marine who served in the Okinawa campaign, recalled a combat-hardened sergeant major breaking down and ordering Manchester and his comrades to launch a suicidal bayonet charge through an artillery barrage. “This was trouble,” Manchester later wrote. “I had seen combat fatigue, and recognized the signs, but couldn’t believe they were coming from an Old Corps sergeant major.” When the barrage lifted, Manchester found the sergeant major spread-eagled outside his fighting hole, “shaking uncontrollably, first shrieking as I once heard a horse shriek, then blubbering and uttering incomprehensible elementary animal sounds.”

What Manchester described became known as “Old Sergeant Syndrome.” Old-timers, even those with enviable combat records, could eventually crack under the accumulated strain of long-term fighting. At first, military doctors and line officers were shocked to see good soldiers, often decorated ones, felled by battle fatigue. They came to realize, however, that even the strongest could crack under combat of sufficient intensity or duration. Army psychiatrist William C. Menninger said those men reacted as “anybody might have if exposed long enough to combat.” The implications were staggering, as psychiatrist John W. Appel observed: every soldier, sailor, or Marine—no matter how tough—was a potential battle fatigue casualty.

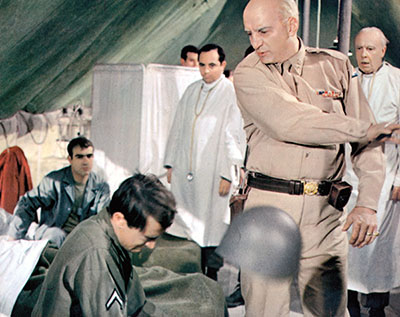

Nevertheless, some old-school officers clung to their belief that the condition was a sign of cowardice or malingering. The most notorious examples occurred in Sicily in 1943. On August 3, Lieutenant General George S. Patton encountered a battle-fatigue casualty, Private Charles H. Kuhl, at an evacuation hospital. Patton cursed Kuhl, called him a coward, slapped him across the face with his glove, and threw him out of the hospital tent. On August 10, Patton encountered another such casualty, Private Paul G. Bennett. Patton cursed him, called him a coward, slapped him, and threatened to shoot him.

These incidents reflected Patton’s firmly held belief that battle fatigue casualties were “cowards [who] bring discredit on the army and disgrace to their comrades” by using “the hospital as a means to escape.” There may, however, have been more to the story. Private Kuhl later said Patton’s conduct that day was so extreme, he thought Patton himself “was suffering a little battle fatigue.” Historian Charles M. Wiltse, author of the army medical service history of the Mediterranean campaigns, agreed with Kuhl, noting that Patton was likely experiencing “the accumulated tensions of the preceding weeks of intensive combat.” Perhaps, as one editorial writer noted, “the difference between the slapper and the slappee was only a matter of rank.”

Doubts about the legitimacy of battle fatigue reached the highest levels of the military. In a memo dated December 30, 1943, U.S. Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall equated the condition with malingering and cited discredited claims from World War I that 80 percent of shell-shock victims had experienced an instantaneous cure the moment the armistice was signed.

Marshall blamed America’s parents and teachers, accusing them of coddling the men, many of whom had grown up during the Great Depression. “While our enemies were teaching their youths to endure hardships, contribute to the national welfare, and to prepare for war,” Marshall wrote, “our young people were led to expect luxuries, to depend upon a paternal government for assistance in making a livelihood and to look upon soldiers and war as unnecessary and hateful.”

Of course, malingering may have occurred. Gunshot or shrapnel wounds are visible and diseases can be diagnosed with objective tests, but there was no definitive test for battle fatigue. Its diagnosis depended on a soldier’s honesty and the skill of the examining physician. In the entire war, only 47 American soldiers were court-martialed for malingering; it is unknown if any faked their symptoms.

Combat troops themselves accepted the reality of the condition as an unfortunate but unavoidable fact of wartime life. “A man who is taken out of combat for battle fatigue,” explained Marine veteran Fred Balester, “is usually no more to blame for his condition than a man who has contracted malaria or been wounded.” As one frontline commander wrote on a soldier’s evacuation tag, “This man now freezes on the trigger and freezes under artillery fire. He is in no way a goldbrick or a coward, but is of no further use as a combat soldier.”

Doctors worked to return battle fatigue casualties to their units as quickly as possible. There was a war going on, and the services needed every man. Battle fatigue was considered a temporary condition and soldiers were treated as near to the front as possible, with an emphasis on relief of symptoms.

Wise commanders learned to intervene when they saw the warning signs. Soldiers were first sent to the battalion aid station, where they got hot food, a shower, new clothing, and a chance to rest. “Hot food, hot drink, a chance to warm up—that’s what [a soldier] needed to keep going,” said Major Richard Winters of the 101st Airborne Division. For mild cases, that was sufficient.

More serious cases went further back to division clearing stations, also known as exhaustion centers. If that did not work, they went to general hospitals. The most serious cases, like the men shown in Let There Be Light, were evacuated to the United States.

Even old-school officers came to grudgingly admit the reality of battle fatigue. Army psychiatrist Edwin A. Weinstein remembered a colonel who encountered such a casualty late in the war. Channeling his inner Patton, the commander drew his .45 pistol, called the trembling soldier a coward, and threatened to shoot him if he did not return to his unit. “Well, Colonel, sir,” the trembling soldier stammered, “I guess you’ll have to shoot me.” The colonel turned to the nearest doctor and ordered: “Evacuate him, he’s crazy.”

As doctors treated more and more battle fatigue cases, they began to understand the impact of precipitating events. The more intense the fight, the greater the number of battle fatigue casualties. A leading cause was artillery fire, since it forced a soldier to sit and take it; other triggers included the death of a buddy or bad news from home, like a “Dear John” breakup letter.

But the most significant factor, doctors learned, was the number of days in combat. A man who had served 200 to 240 days in combat was no longer an effective soldier. If he had not yet broken, he was often too jittery or overly cautious. Men with fewer than 200 days were the most likely to respond to short-term treatment and to return to their units. These findings presented a dilemma because the army had no formal rotation policy for transferring combat veterans home. Most soldiers were overseas “for the duration”—until they were killed, wounded, or the war ended.

Despite a better understanding of the issue and better treatment of afflicted servicemen, battle fatigue remained a problem until the end of the war. In 1945, 280,110 soldiers were hospitalized for battle fatigue, with 120,561 discharged for psychiatric reasons. In the navy, battle fatigue casualties increased late in the war as sailors endured the terror of kamikaze attacks.

After V-J Day, the military refocused on treating the affected men and preparing them to re-enter civilian life. That is where it hoped to get a boost from Let There Be Light.

In April 1946, critics and filmgoers eagerly an-ticipated the film’s premiere at the Museum of Modern Art. But at the last minute, the army pulled the film. Huston later claimed army MPs showed up and physically seized the film and classified it restricted, making it unavailable to civilian audiences.

Critics who had already seen previews of Let There Be Light were livid. James Agee, writing in The Nation, called the suppressed film an “intelligent, noble, fiercely moving short film” and lamented that it “will probably never be seen by the civilian public for whose need, and on whose money, it was made.” He urged public pressure to get the army to change its mind. “If dynamite is required,” he wrote, “then dynamite is indicated.” New York Post critic Archer Winsten took solace in his belief that the film would eventually be released. “Some future audience is guaranteed not only a beautiful film experience,” he wrote, “but also the certainty that their generation has better sense than ours.”

The army’s stated reason for suppressing the film was privacy. It did not want to stigmatize any identifiable ex-soldier as a psychiatric casualty. Indeed, an army directive from 1944 prohibited the release of the “names or identifiable photographs of neuropsychiatric cases.” Huston had anticipated this objection and obtained privacy waivers from those in the film, but officials questioned the ability of psychiatric patients to truly give informed consent. When Huston later went to retrieve the releases from an army file cabinet, he said, they had disappeared.

Some believed privacy was not the army’s real objection. Agee suggested it was concerned that the film was so powerful that any man who saw it would think twice before enlisting. Huston felt the army wanted to maintain “the ‘warrior’ myth, which said that our soldiers went to war and came back all the stronger for the experience, standing tall and proud for having served their country well.”

The army’s own actions seemed to undermine its stated concern for the soldiers’ privacy: it had supplied nearly a dozen still photos from Let There Be Light to illustrate an October 29, 1945, Life magazine article on the stateside treatment of battle-fatigue casualties. The photos clearly showed the faces of two men in the film and identified them as psychiatric patients. The army never explained why these photos were acceptable for Life’s civilian readers while the film was not.

Instead, the army commissioned Joseph Henabery—a director and actor who, in 1915, had played Abraham Lincoln in D. W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation—to produce a new film. Henabery’s film, Shades of Gray, was scripted, not spontaneous, and used professional actors instead of actual veterans. The result was what film historian Scott Simmon called “less a remake of Let There Be Light than an argument against it.”

Shades of Gray suggested that preexisting mental illness was the cause of battle fatigue—a far different message than delivered in Let There Be Light, and not what military doctors had learned during the war. The narrator contended that one out of every 18 Americans would eventually be treated at a mental hospital—and that an army is no stronger than the population from which it is drawn. Even the title follows this theme, with shades of gray symbolizing the varying degrees of mental illness that, the narrator claims, all civilians and soldiers carry with them. When the army released Shades of Gray to the public in 1948, an army spokesman emphasized that the film was “definitely not connected in any way with Let There Be Light.”

Meanwhile, American servicemen returned home with very real struggles. One such “new civilian” was William S. Freeman Jr. For many Thanksgivings after the war, Freeman stood in his yard and wept while his family enjoyed turkey dinner. He was haunted by memories of Thanksgiving 1944, when his men, lined up for a turkey meal served in canisters, were decimated by German artillery. Freeman’s enduring memory, he wrote, was “men torn to shreds around busted up turkey canisters.”

Ira Hayes, one of the famed flag raisers of Iwo Jima, died from overexposure to the cold and alcohol poisoning in January 1955, at age 32. In the decade since the war, he had accumulated more than 50 alcohol-related arrests.

Audie Murphy, the most decorated American soldier of World War II, suffered from battle fatigue for the rest of his life. He endured chronic insomnia and recurring nightmares, and kept a loaded pistol under his pillow. He eventually took to sleeping alone in his garage with the lights on. Murphy recalled being terrified while acting in 1951’s The Red Badge of Courage, as the film’s Civil War battle scenes reminded him of his wartime experiences and left him trembling. The director of the film? John Huston.

Of the soldiers who appeared in Let There Be Light, nothing is known of their postwar lives. As for the men Patton slapped in Sicily, both survived the war. Charles Kuhl worked as a janitor for the Bendix Corporation and died of a heart attack in 1971 at age 55. Paul Bennett later served in the Korean War and died in Georgia in 1973 at age 51.

YEARS AFTER THE WAR, Let There Be Light was largely forgotten except by a small group of film aficionados. An unofficial copy circulated among them, reportedly “liberated” by a sharp-eyed film-buff soldier who had seen it in an army film library at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey.

In 1980, film historian and reporter Joseph McBride began a campaign for the film’s release and filed a request under the Freedom of Information Act. He soon gained important allies, including Jack Valenti, president of the Motion Picture Association of America, Vice President Walter F. Mondale, and film producer Ray Stark. While the army continued to voice misgivings about the privacy of the soldiers, army secretary Clifford Alexander Jr. ordered its release in late 1980.

The film premiered on January 16, 1981, at the Thalia Theater in Manhattan, nearly 35 years after the army blocked its original premiere. Critics were impressed with the film’s raw power. Michael Blowen of the Boston Globe called it “single-minded in its riveting portrayal of the mental fallout of war,” and Michael Kernan of the Washington Post thought it showed “just how delicate and yet how resilient the human mind can be.” The men’s faces haunted David Denby of New York magazine. “Seeing them break down is almost unbearable,” he wrote.

But critics also noted shortcomings that may have escaped notice 35 years earlier. To Vincent Canby of the New York Times, “the impression given and even encouraged by the film is of a series of miraculous cures.” Indeed, said Andrew Sarris of the Village Voice, the film attributed to army psychiatrists “the combined talents and powers of Mandrake the Magician and Bernadette of Lourdes.”

What was omitted, noted Stanley Kauffmann of the New Republic, was any mention of “the possibility of recurrence in these men; and, worse, it says nothing about the sufferers with combat psychoneurosis who took longer to leave or who never got out of hospitals.” Perhaps, he suggested, suppression had given the film a better reputation than it deserved. What had been shocking and ground-breaking in 1946 was neither to current audiences who had “grown up seeing riots, wars and assassinations live-and-in-color” on TV, Canby asserted.

Interest in Let There Be Light was revived in 2012, when the National Archives and Records Administration fully restored the film. It is now available online for all to see. While its cinematic techniques seem dated and the treatment methods quaint, the film stands the test of time as a stark reminder of the thousands of soldiers, sailors, and Marines whose wounds were not visible or physical—the men who were the hidden casualties of the war.✯

This story was originally published in the March/April 2017 issue of World War II magazine.