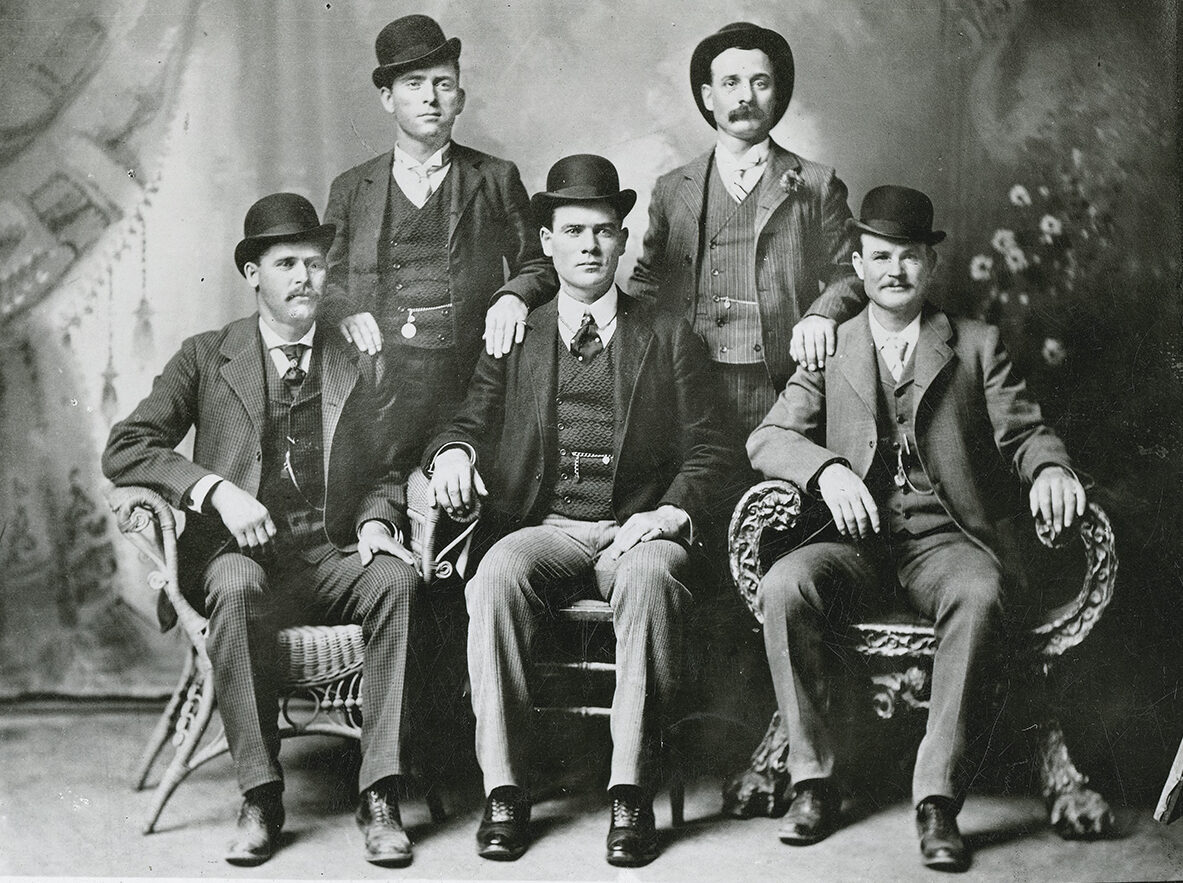

It is one of the most famous photographs in Western history. Five well-dressed outlaws gaze into the camera—two of them destined to be immortalized 69 years later in the Paul Newman–Robert Redford film Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. They since have been dubbed the “Fort Worth Five,” as they sat for the portrait in a Fort Worth, Texas, studio. But the identity of the photographer and the story of how the picture became a national phenomenon are equal parts myth and misinformation. Interviewed in the August 2008 Wild West, the late Bob McCubbin, a noted collector of Old West photographs and then president of the Wild West History Association, repeated the old canards that the photographer had placed the image “in his studio window” and made copies “for distribution to law enforcement around the country,” neither of which is true. Following is the real story, told for the first time, of how five outlaws came to have their picture taken in a Fort Worth studio on a November day in 1900—and why a sixth man and seventh man were just as important toward making that photograph an icon of Western history.

‘laying low’ in fort worth

It all started with the robbery of the First National Bank in Winnemucca, Nev., at noon on September 19, 1900, by a trio of men, members of a gang loosely styled the “Wild Bunch.” The nucleus of the gang consisted of Harvey Logan (aka “Kid Curry”), George “Flat Nose” Currie, Ellsworth “Elzy” Lay, Robert LeRoy Parker (aka “Butch Cassidy”) and Harry Alonzo Longabaugh (aka “the Sundance Kid”). Historians have called them the last and greatest Western outlaw band. For roughly five years (1896–1901) the Wild Bunch bedeviled law enforcement, eluding pursuit by some of the most respected lawmen of their day, including Joe LeFors, Lowell Spence, Charles Siringo and William Pinkerton. Although there was some mystery at the time about the identities of the Winnemucca robbers, all evidence points to Butch, Sundance and newcomer Will Carver. (There is no credible evidence that a fourth outlaw, Ben Kilpatrick, was waiting with fresh horses outside of town.) As the robbery involved a national bank, it brought in not only state and local authorities but also the feds; the gang could not just ride across the border into Utah or Idaho to make its getaway.

The boys headed south to drop out of sight and enjoy a little R&R with their loot—more than $32,000 in gold coins. They found their way to Fort Worth via the Fort Worth & Denver City Railway. Fort Worth in 1900 had almost 27,000 people and two busy train stations. The boys could easily have slipped into town without being noticed. In fact, Butch and Sundance, posthumous fame to the contrary, were almost unknown to Texas lawmen at the time.

It was in the little city on the Trinity that the Fort Worth Five came together. Joining Butch, Sundance and Carver were Ben Kilpatrick (aka “the Tall Texan”) and Harvey Logan. At the time Logan had the biggest reputation, being wanted for murder, armed robbery and jailbreaks in no fewer than seven Western states or territories. Everyone, it seemed, was after Logan, if not his confederates, and Fort Worth was a good place to lie low until the heat died down.

The boys spent several weeks (November–December) together in what was part reunion and part “howdy” affair. While they knew each other by reputation, they had never all worked together on the same job, so getting acquainted was an important element of their visit. They made the most of it, partaking of Fort Worth’s lowbrow pleasures, specifically, the girls and the saloons. While making the rounds, they holed up at a nondescript boardinghouse named Maddox Flats. The boys could have afforded any of the city’s first-rate hotels, but they were more comfortable staying in the sort of cheap walk-up favored by those who crave anonymity.

They felt safe on the streets of Fort Worth, 1,600 miles from the scene of their latest crime, and had no reason to suspect that either the Pinkertons or Wells Fargo could track them there. They could carouse in public, throw around money and sleep in real beds. Following their usual pattern, sooner or later they would blow all their illgotten loot or just get antsy to get back to “work,” whereupon they would hit the road and disappear as mysteriously as they had arrived.

An indication of just how safe they felt is that Will Carver tied the knot with Callie May Hunt (aka “Lillie Davis”), a well-traveled prostitute then working for a local madam. Their marriage license is dated December 1, 1900. The other boys preferred to keep their amorous options open at this point.

an ill-considered pose

For reasons unknown, on November 21, a Wednesday, the boys decided to dress up and have their portrait taken in one of the city’s professional studios. (There is no doubt about this date, as it is printed on the individual mug shots subsequently reproduced for the Pinkerton circulars.) They seem not to have been celebrating any particular occasion, unless it was Will and Callie May’s engagement. Perhaps they wanted to hit some of the high-tone uptown saloons such as the Palais Royal, which admitted only “gentlemen.” Or they may have sat for the portrait on a lark, as a keepsake of their visit to Fort Worth. Regardless, such an appalling lapse in judgment must have been liquor-fueled.

The portrait studio they picked was John Swartz’s gallery at 705½ Main. (The 700 block was on the edge of Hell’s Half Acre, an area of cheap saloons and bawdy houses; the “½” part of the address indicates it was upstairs.) Fortytwo-year-old Swartz and brothers David and Charles had been working in the city as photographers since 1885. In 1888, after a three-year apprenticeship with eldest sibling David, John had struck out on his own, and by 1896 he had established himself as a respected photographer. Like many professional photographers of the day he favored an upstairs location to take advantage of natural lighting. John considered himself an artiste, not just a technician, and guaranteed that customers would find his portraits both “artistic and attractive.”

Swartz’s medium was the cabinet card, which had been around since the 1860s. The image was mounted on heavy stock with the photographer’s logo and other information often printed on the front. It was the preferred format for a formal sitting, and John was a master of the studio portrait. In February 1900, Eastman Kodak had introduced the dollar Box Brownie camera, which allowed any yahoo to become a photographer. If the boys had simply bought a Brownie and snapped away, they could have spared themselves a lot of grief. But they opted for the old-fashioned formal studio portrait.

Swartz’s gallery sat above Sheehan’s saloon, which may have been where the boys hatched the portrait idea over a few rounds. The fancy duds they wore did not represent much of an investment for a bunch of high rollers living off stolen loot. They could have purchased the outfits off the rack and added the bowlers for no more than $3 or $4 dollars per man. The nicest men’s clothing store in Fort Worth at the time was Washer Brothers, at Eighth and Main streets, where they would have been treated like gentlemen and still gotten a good price. Regardless of where they got their attire, these were not rented or borrowed clothes.

The boys climbed the stairs on the side of the building to the second floor and entered Swartz’s well-appointed waiting room. There they must have admired examples of the photographer’s work on display. Swartz was running one of his periodic specials, 12 pictures for $1.75. The cost for the same pictures in Kansas City or St. Louis would have been anywhere from $2.50 to $5 per dozen. The boys probably ordered a dozen, took two prints each, and in a burst of generosity let the photographer keep one or two for himself. Or perhaps Swartz just liked the five- man portrait so much he made a copy for himself.

Dressed to the nines and well lubricated, the boys were ready for their close-up and would have agreed with the subsequent assessment of a newspaper reporter that they were a “dudishlooking” bunch. All Swartz had to furnish for the shoot were three chairs and a painted canvas backdrop. He arranged his subjects (although they may have had some say in the matter) with Longabaugh, Kilpatrick and Cassidy seated in front, left to right, and Will Carver (left) and Harvey Logan (right) standing behind them. It’s possible Carver and Logan stood because they were the big shots of the gang, as 19thcentury photographers commonly had the most important member(s) of any grouping stand for a portrait. If that was the case, it is ironic, given how the relative status of the Fort Worth Five later turned upside down. Regardless of his importance at the time, Logan, eyes unfocused and a bowler pushed back on his head, looks about three sheets to the wind.

The boys may have returned the next day to pick up their prints. Swartz probably never saw them again after that, as they skipped town after Will and Callie May got hitched. Perhaps they were beginning to feel the heat of the national manhunt, or maybe they had just grown bored and were ready to move on. In any event they had scratched their itch to pose for posterity. The boys had indulged their collective vanity, had some fun and had no reason to pay a third visit to the studio. For his part, Swartz was so impressed by his portrait of the five strangers that he made the fateful decision to display a copy in a prominent place in his waiting room.

the portrait goes public

Most of the story to this point is conventional. Now, however, the tale enters previously unexplored territory. Wild Bunch aficionados have always claimed that John Swartz placed the photo in his front window, where either a passing Pinkerton operative or Wells Fargo detective recognized the outlaws and arranged to distribute their mug shots across the West. There are two main problems with this scenario. First, no one has ever been able to provide the name of the alleged Pinkerton operative much less explain what he was doing in Fort Worth. Early Wild Bunch historian Charles Kelly suggested the agent was Wells Fargo’s Fred Dodge, but Dodge never makes such a claim in the detailed diaries he kept. Second, no passerby on the street could have seen any photo through the window of Swartz’s second-floor studio; the only way to see examples of the photographer’s work was to go upstairs and enter his waiting room.

Western historians do agree that John Swartz took the picture and that it was the key element in the downfall of the gang. The real story of how the portrait went national is more interesting than either the Pinkerton or Wells Fargo scenario. The first person to recognize the importance of the photo was Fort Worth detective Charles R. Scott, a 21-year veteran of the Fort Worth Police Department who had started out as a beat cop and worked his way up to chief detective by 1900. Scott was in charge of the department’s “Rogue’s Gallery,” mug shots of every perpetrator booked in town, as well as photos sent to Fort Worth by other agencies. To obtain mug shots, city police had to escort prisoners to a professional studio. Swartz was the photographer of record for the department in 1900. It was not glamorous or artistic work, but it provided a steady little income.

It was Scott’s job to take perps down to 705½ Main for their sittings and then return later for their mug shots. He was on one such run when he caught sight of the Wild Bunch photo displayed in Swartz’s waiting room. As a veteran detective and keeper of the FWPD Rogue’s Gallery, he had seen enough wanted circulars of Harvey Logan and Will Carver to recognize them. Scott once boasted to a newspaper reporter, “There is not a thief or smooth man in the country who can drop in here [Fort Worth] without being spotted at once.” On top of that, he had a good secondhand description of the pair from his brother Hamil Scott, who had been the Wells Fargo express agent on the Texas Flyer when it was held up near Folsom, New Mexico Territory, on July 11, 1899, by the Ketchum Gang (Sam Ketchum, Elzy Lay, Will Carver and Harvey Logan). Two of the three were not masked (Carver and Logan?), and as Hamil Scott told superiors afterward, “I would know them anywhere.”

Now something clicked in Charles Scott’s memory. Taking the photo from Swartz’s waiting room, he rushed back to headquarters to check it against his files. He knew or could guess at the identities of three of the men in the photograph (Logan, Carver, Kilpatrick), either from the Folsom robbery or their Texas connection. Someone else would have to identify the other two. Elated at his discovery, Scott quietly raised the alarm. The first thing he learned was that “the birds had already flown the coop.” All he could do was get word out to those who could use the information.

Scott wired the nearest office of the Pinkerton National Detective Agency, in Denver, whose operatives were definitely interested in his lead. The portrait was what one Pinkerton man, interviewed later by The San Antonio Light, called their “first real break” in tracking down the Wild Bunch. Scott forwarded the photo to them, though not until he had shown it around town, bragging about breaking the case. Pinkerton was not ready to celebrate just yet. It issued the first wanted circulars on May 15, 1901. The only three outlaws from the group portrait to appear on that first circular were Parker, Longabaugh and Logan—each in a cropped mug shot with such vital information as height, build, complexion and eye color. It was thanks to the Pinkerton agency (not John Swartz) that “every law officer and hundreds of watchful civilians got copies of the photograph,” stated one of its operatives years later.

mug shot to manhunt

How significant was the Fort Worth Five photograph? In August 1902 (Mich.) Times The Bay City did a little early-day “Photoshopping” to pull just Longabaugh and Cassidy out of the original, labeling them “the two most desperate bandits in the country.” Four years later The Lexington (Ky.) Herald reprinted the original portrait but added the known fates of the five, their names printed beneath the image. From Texas to the Great Lakes, John Swartz’s photograph had become national news. Who knows how long the Wild Bunch might have continued to operate with impunity if not for the outlaws’ impulsive visit to his studio.

The photo didn’t just break the Wild Bunch manhunt wide open; it also became part of Fort Worth lore, and for years local historians searched old newspapers for anything to confirm the provenance of the picture. Focusing on the period 1901–02, they drew a blank. One mystery was why the Fort Worth papers made no mention of the outlaws’ historic 1900 visit, even after authorities fingered three of them as the men who had held up the Winnemucca bank and pulled other jobs throughout the West. The silence in the newspapers was deafening—and inexplicable. The question of the photo’s provenance became more than just a scholarly debate; it had the potential to cause Fort Worth great embarrassment, given that its multimillion-dollar business district, redeveloped in the 1980s, was dubbed “Sundance Square” in tribute to one-half of the infamous outlaw duo.

Now we can at last verify the Fort Worth provenance of the John Swartz studio portrait: The proof comes from a November 23, 1902, Fort Worth Telegram article naming detective Charles Scott as the man who discovered the photograph and adding that the tip-off for Scott was recognizing Harvey Logan among the group. This newspaper item in turn calls for re-examination of the very history of the Wild Bunch, particularly the pecking order of the Fort Worth Five. It was later writers and filmmakers —starting with Charles Kelly and his 1938 book The Outlaw Trail: A History of Butch Cassidy and His Wild Bunch—who first crowned Cassidy and the Sundance Kid the gang leaders, relegating Logan and Will Carver to supporting roles. But the lawmen who chased the boys in 1900 considered Logan the true head of the Wild Bunch.

Like most newspaper articles, the November 1902 Fort Worth Telegram item scrambled some of the facts. It placed the date of the gang’s visit a year later—after the July 3, 1901, Wagner, Mont., train job—and mentioned only “three pals” in the picture with Logan, not four. But it is clear nonetheless the reporter is referencing the celebrated Swartz portrait.

credit where credit is due

It’s not hard to figure out why the true story behind the famous photo was lost to time. Detective Scott died on April 7, 1902, seven months before local papers broke the story of the outlaws’ historic visit, and by year’s end the gang itself was finished. Authorities in Sonora, Texas, cornered and killed Will Carver on April 2, 1901. Ben Kilpatrick was arrested in St. Louis on November 5, 1901, convicted of passing stolen federal banknotes and sentenced to 15 years in the penitentiary. (He served 10.) Harvey Logan was arrested near Jefferson City, Tenn., in December 1901, escaped from jail in Knoxville in June 1903, then was shot down near Parachute, Colo., in June 1904 after robbing one more train. At the time he was, as historian Jay Robert Nash puts it, “the most hunted outlaw in America.” Butch and Sundance, with the Kid’s paramour Etta Place, wisely skipped the country in early 1901, sailing to South America, where both likely died in a shootout with Bolivian soldiers in November 1908. Their downfall all began with the Fort Worth photo. It’s no wonder a Pinkerton agent dubbed it the “bad-luck picture.”

As for poor Charles Scott, he never got the credit he deserved for putting the soon-to-be famous photo into circulation. In a testimonial by Fort Worth Police Chief Bill Rea at the time of Scott’s death, Rea stated he could not recall “any great cases in which Mr. Scott was responsible for bringing criminals to justice.” Rea did, however, provide the key as to how Scott was able to break the Wild Bunch case wide open: “He knew by sight almost every professional thief in the Southwest.” Unfortunately for Scott’s legacy, by the time the authorities connected all the dots and smashed the Wild Bunch, the detective was no longer around to explain his role in stopping the gang.

As for the other uncredited star of the case, John Swartz continued to operate his photography studio in Fort Worth until 1912 (see another of his photos on P. 16 of this issue), but those were not happy years. He was falling ever deeper into debt, and his marriage was crumbling, leading him finally to sell out to a rival, lock, stock and glass plates. Sometime after 1920, his wife and children gone, he decided to get out of the business completely and leave Texas, returning to the family farm in Mount Jackson, Va., where some 40 years earlier the young man had dreamed of going West to become a professional photographer. Now he was a broken man with no family and no career, only a roof over his head provided by older brother Lemuel. On January 17, 1937, Swartz, 78, died at Manassas, Va. The following year historian Charles Kelly published The Outlaw Trail.

The Swartz brothers left behind a substantial if unacknowledged body of work, all of it Texas-focused. When researchers sought the story behind John’s Fort Worth Five portrait, they always looked in the wrong direction, crediting either the Pinkertons or Wells Fargo with breaking the case and focusing on San Antonio instead of Fort Worth. William Pinkerton even traveled to San Antonio to interview notorious Madam Fannie Porter, reputedly a confidante of the gang, and she filled the famous detective with lots of blarney. He spent no time in Fort Worth. Pinkerton’s flawed investigation became the starting point for waves of Wild Bunch historians who followed—some respected, some not so respected. None could ever fit all the pieces together.

An iconic, if infamous, image

The parade passed by Charles Scott and John Swartz. The only folks ever to cash in on the Fort Worth Five have been the dealers and collectors who buy and sell the copies of the photograph that occasionally come on the market. No one knows how many first-generation images exist, but everyone agrees it’s a seller’s market. The latest sale of an “original” Wild Bunch photo went in 2000 to a Canadian collector for a cool $85,000.

Today the legend of the photograph is too big to be killed off. It will keep its hold on the public consciousness long after this article has been forgotten. That’s the way collective memory works. And, like every legend, it has many versions. The Smithsonian Web site floats the preposterous tale that the boys sent a copy of the photo to the Pinkertons. They were never that drunk. The Web site also relates the more credible story that the boys had the effrontery to send a copy to the Winnemucca bank along with a thank-you note from Butch. The number of copies of the photograph in public and private hands today seem to support the conclusion that the five Wild Bunch members purchased Swartz’s “12-fora-dollar-seventy-five” special.

In 1999 the Smithsonian named the picture one of the iconic images of the American West, and today it resides proudly in the holdings of the National Portrait Gallery, the Library of Congress, the Denver Public Library’s Western History Collection and the University of Oklahoma Libraries’ Western History Collections, among other repositories. Historians frequently request the image as they churn out a never-ending stream of words about the gang. TheWild Bunch shares that rare kind of cult following in Western history enjoyed by such figures, events and places as George Armstrong Custer, the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral and the Alamo.

So give Charles Scott his due as the sharp-eyed detective who first recognized the importance of the picture, but also give credit to photographer John Swartz. Without the iconic image he created with his camera—perfectly capturing the spirit, the look and the defiant confidence of the Wild Bunch— there would be no legend of the Fort Worth Five. Swartz created five timeless celebrities that day.

Wild West frequent contributor Richard Selcer and co-author Donna Donnell write from Fort Worth. Suggested for further reading: Butch Cassidy: A Biography, by Richard Patterson; and The Sundance Kid: The Life of Harry Alonzo Longabaugh, by Donna B. Ernst. Originally published in the December 2011 issue of Wild West.