World War II was a global conflagration that transcended geography and time itself—a fact best illustrated on the day the shooting stopped. In the Western Pacific on August 14, 1945, thousands of American airmen took off in wartime and landed in peacetime after midnight. Almost simultaneously, Allied and Japanese fliers fought and slew one another on August 15, mostly without knowing that Tokyo had agreed to surrender.

It had much to do with time zones.

Over the previous several days rumors and conflicting reports had skittered over radio broadcasts from Washington, D.C.: Japan was about to surrender; Japan was not surrendering. On the 10th, Tokyo had announced tentative acceptance of the Allies’ Potsdam Declaration calling for Japan’s unconditional surrender, provided that the emperor kept his throne. Meanwhile, the Japanese war cabinet remained divided over surrendering. The situation remained tentative, viscerally uncertain.

The U.S. Twentieth Air Force had destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki with atomic bombs on August 6 and 9, immediately followed by the Soviets’ declaration of war and invasion of Japanese-held Manchuria. As Japan reeled under the triphammer blows, millions of people anticipated Tokyo’s capitulation. Days passed in gnawing uncertainty.

After 45 months of combat across the world’s greatest ocean, U.S. servicemen were bone weary from the sanguinary slogging that ponderously advanced westward from Hawaii to Honshu—at an average rate of about three miles per day. In that time more than 400,000 Americans had died in combat or from war-related causes in defeating first Italy, then Germany and now perhaps Japan. Men were tense, dubious, sleep-deprived. They did not know what to believe.

On the afternoon of August 14 (Tokyo time), Maj. Gen. Curtis LeMay’s powerful XXI Bomber Command launched 750 B-29s from the Mariana Islands, some 1,500 miles south of Japan. Deployed in seven task forces, the Boeing firebirds were to target transport and oil targets, with overhead times between midnight and 3 a.m.

The largest contingent was 140 Superfortresses of the 315th Bomb Wing, led by Brig. Gen. Frank Armstrong, an extraordinary airman and officer. He had led the first U.S. strategic bombing mission in Europe almost exactly three years earlier, striking transport targets in northern France. Since then he had exchanged his B-17 for a -29, and now headed what would likely be the last heavy bomber mission of the war—perfect bookends to a unique career.

Recommended for you

It was XXI Bomber Command’s longest nonstop mission: 3,700 miles round trip to a refinery 300 miles north of Tokyo. Employing the wing’s new high-definition Eagle radar, Armstrong’s bombardiers smothered the target and turned for home after more than eight hours en route.

On the way back, the 8,250 men in LeMay’s bombers were acutely aware that they might be caught in a time warp. Radio operators eagerly monitored Radio Saipan and other stations, anticipating confirmation of the war’s end.

In a stunning tribute to LeMay’s leadership and his command’s professionalism, every bomber returned to base that morning. Meanwhile, Frank Armstrong mused: “Every man aboard our aircraft was outwardly jubilant, but inside each experienced mixed emotions. We wanted no more of war, but it was difficult not to think of those who had not lived to see the dawn of this day. These thoughts brought waves of sadness, irony and gratitude. Too, there was a sudden surge of awe. Some of us had been in the business of killing for nearly four years. How would we adapt to a peaceful existence, and how much would we regret the havoc we had wrought, even though it had been absolutely necessary?”

Then the U.S. State Department declared that, despite the unconditional surrender dictate from Potsdam, Emperor Hirohito could remain. Unknown to the Allies, that set off a bitter dispute, with the “big six” ruling Tokyo still divided. At that point the emperor personally intervened, stating that Japan would “bear the unbearable” and surrender.

President Harry Truman announced the news in the evening of the 14th, Washington time. He concluded, however, “The proclamation of V-J Day must await upon the formal signing of the surrender terms by Japan.”

The United Newsreel showed two million New Yorkers jammed into Times Square. “It’s all over, total victory,” the narrator intoned. “All night long the rejoicing continues. Never before in history has there been greater reason to be thankful for peace.”

Thus began a three-day spree of joyous celebration and drunken revelry. But off Japan, the killing continued.

Across the international date line, where LeMay’s bombers were returning to their roosts, the U.S. Third Fleet had already launched two of three scheduled air strikes on the morning of the 15th. Admiral William F. Halsey’s command had monitored communications during the night, keeping options open for continued operations or a stand-down. But when Admiral Chester Nimitz’s Pacific headquarters could not confirm Tokyo’s surrender, he directed Halsey to continue hostilities in the morning.

The Third Fleet’s striking arm was Task Force 38, the most powerful military force on any ocean: more than 90,000 men aboard 106 ships with 17 fast carriers, including Britain’s HMS Indefatigable. They carried more than 1,300 fighters, dive bombers and torpedo planes—larger than some air forces. Vice Admiral John S. McCain was a Johnny-come-lately to aviation but he had the seniority needed to command Halsey’s carriers, and his staff was up to the task. His fleet air operations officer, Captain John S. “Jimmy” Thach, was an outstanding Navy fighter tactician who ran much of the task force for McCain.

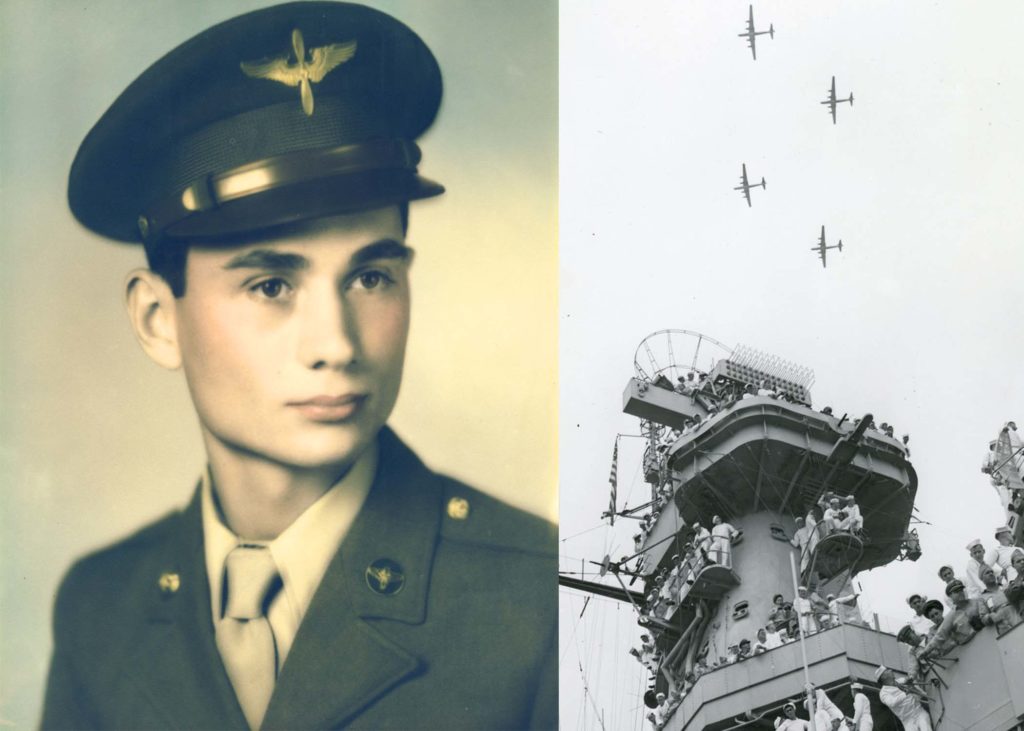

Some aviators had been fighting since 1942, or even earlier. Leading Fighter Squadron 86 (VF-86) from USS Wasp was Lt. Cmdr. Cleo J. Dobson, survivor of Enterprise’s unwelcome greeting over Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. He still ached for a shot at a Japanese aircraft.

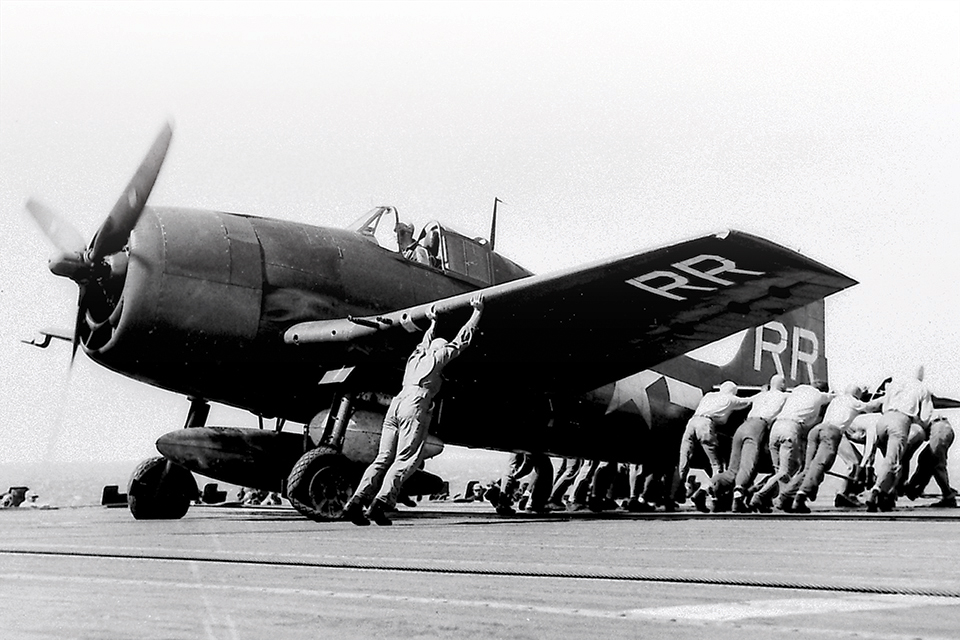

Strike Able, with 103 aircraft, launched at 5:30 a.m. against airfields and other facilities around Tokyo. But the first enemy contact that morning was made by Vought F4U-1D Corsairs off Essex. At 5:40 newly promoted Lt. Cmdr. Thomas Hamil Reidy latched onto a long, lean bogey near the task force. He closed in, identified it as a speedy Nakajima C6N1 Myrt recon plane and dropped it into the spume-tossed gray ocean. It was Reidy’s 10th victory, making him the last double ace in U.S. Navy history.

Reidy subsequently received accolades for having scored the last aerial victory of the war. But another ace, Belleau Wood’s 21-year-old Lt. (j.g.) Edward Toaspern, actually carved his final notches after Reidy that morning when he downed two Mitsubishi A6M Zeros over land.

Belleau Wood’s Air Group 24 was nearing its target when bandits tried to intercept about 25 miles off Inubosaki Lighthouse, a familiar coastal landmark. Four Grumman F6F-5 Hellcats splashed six single-engine fighters, two by pilots who had never scored before.

San Jacinto, the “flagship of the Texas Navy,” launched its first strike overland off Mito, 45 miles northeast of Tokyo. An estimated 20 Japanese fighters engaged VF-49, which claimed seven kills and two probably destroyed without loss.

At 6:30 the first fighter-bombers were in their dives when the fleet broadcast the cease-fire order: “All Strike Able planes return to base immediately. Do not attack target. The war is over!” The Third Fleet learned that Japan had agreed to surrender, accepting the Allies’ offer to retain the emperor.

However, Ticonderoga’s Hellcats continued their attack rather than pull out of their dives at medium altitude within range of anti-aircraft guns. Lieutenant (j.g.) John McNabb was the “tail-end Charlie,” and his 500-pound bomb probably was the last one dropped on Japan.

In some squadrons, air discipline unraveled. Pilots broke formation and indulged in joyful aerobatics at the sheer thrill of being alive.

Among the inbound planes in Strike Baker was Essex’s Air Group 83. Ensign Donald McPherson, a Nebraska ace, said: “We VF-83 pilots were part of a large attack force that was approaching the Tokyo Bay area when we were informed by radio of the ‘cease fire.’ We were to proceed back over the ocean and to jettison our bombs and rockets. After following those orders we broke formation and ‘celebrated’ by doing all kinds of aerobatics! What great feeling to have ended the conflict victoriously!”

The third strike force’s aircraft shut down engines on their carriers’ flight decks. Bombers were struck below to hangar decks while fighters stood by to reinforce the combat air patrol.

Meanwhile, an impromptu celebration erupted in Task Force 38. Men either shouted and pounded the backs of shipmates or stood frozen in place, trying to absorb the message. Aboard scores of ships, sailors took turns tugging lanyards that blared steam whistles. Many men blasted out the Morse Code dot-dot-dot-dash. V for victory.

All offensive operations were cancelled at 7 a.m., but fleet defenses remained on full alert. And the killing continued.

Whether from ignorance or anger, numerous Japanese airmen continued resisting the intruders. Hardest hit was Yorktown’s VF-88, flying a joint mission with 24 Corsairs off Shangri-La and Wasp. Lieutenant Howard M. Harrison’s dozen Hellcats were dispersed in worsening weather, leaving six intact upon penetrating a cloud front.

“Howdy” Harrison was enormously popular with his shipmates. They considered him the “friendliest, straightest guy you could ever meet.”

Overflying Tokorozawa Airfield northwest of Tokyo when the cease-fire message was broadcast, Harrison was about to reverse course when the roof fell in. An estimated 17 enemy aircraft—reportedly a mixed bag of imperial army and navy types—dropped onto the Grummans from above and behind. It was a near perfect “six o’clock” attack.

The attackers were from the 302nd Kokutai (naval air group), based at Atsugi. They had scrambled eight Zeros under Lieutenant Yutaka Morioka, a former dive bomber pilot with four victories, as well as four Mitsubishi J2M3 Jacks, big, rugged fighters with four 20mm cannons.

Morioka set up the bounce well, hitting the Americans at 8,000 feet. Spotting the threat, Harrison knew there was no choice but to fight. His pilots shoved throttles to the stops, maneuvered for a head-on attack and opened fire. In that first frantic pass the Yorktowners thought they dropped four bandits, but the formations were shredded and the combat turned to hash.

Fighting 88 was a tight-knit outfit. The previous week Lts. (j.g.) Maurice Proctor and Joseph Sahloff had volunteered to cover Harrison, who had ditched off Mito. They led the rescue amphibian to Harrison’s tiny life raft, knowing that otherwise he likely would not be found.

Now, as Proctor took up a protective position off Sahloff’s damaged Grumman, tracers streaked past his wings. He turned hard to starboard and Lt. (j.g.) Theodore Hansen shot the Japanese off his tail. Proctor and Hansen rejoined above Sahloff, observing two more Japanese planes afire but could not identify the victors.

Abruptly Proctor was boxed in: six bandits ahead and one astern. Unaccountably, the attackers on his nose pulled up, allowing him to engage the stalker behind him. He scored decisive hits, sending the enemy down burning.

By the time the enemy sextet returned, Proctor had enough of a start to dive toward some protective clouds. The Japanese hit his plane but he evaded through the weather, reaching the coast.

There Proctor saw Sahloff’s crippled Hellcat spin out of control and crash into the sea. But Proctor couldn’t locate the others, and though he radioed his shipmates for a rendezvous, only Hansen replied.

Hansen returned to the ship alone, sick at heart, believing he was the lone survivor. His spirits rose when Proctor trapped a few minutes later. In the debrief of the hard-fought combat Hansen claimed three victories and Proctor two. Subsequently the intelligence officer awarded one victory each to the pilots killed in action: Sahloff, Harrison and Ensigns Wright Hobbs and Eugene Mandeberg. It had been Hobbs’ 23rd birthday.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Postwar analysis of available Japanese records indicated that the 302nd Kokutai had lost one Zero and two Jacks. The only confirmed success went to Morioka, achieving ace status on the last day of combat.

The Royal Navy’s Indefatigable contributed a mission that morning against a chemical plant during which six Grumman Avengers escorted by eight Supermarine Seafires were jumped by perhaps a dozen Zeros. The Seafires, though based on the RAF’s immortal Spitfire, carried heavy drop tanks that limited their performance. With no choice, the British aviators turned to engage, some unable to shed their external fuel.

Hit in the first pass, Sub-Lt. Fred Hockley bailed out of his crippled fighter. However, despite 20mm cannon malfunctions, his squadron mates claimed eight Zeros while an Avenger made a safe water landing.

Because of continuing Japanese probes, the Americans were leery of any inbound aircraft. When Royal Navy Sub-Lt. Victor Lowden was threatened by inquisitive Corsairs, he lowered wheels and flaps, banking steeply to show his Seafire’s distinctive elliptical wing with blue and white markings.

Meanwhile, Japanese conventional bombers and kamikazes still posed a threat. A Corsair from Hancock splashed a Yokosuka D4Y Judy dive bomber attacking Indefatigable that morning, as the British carrier narrowly avoided two bombs.

Halsey responded with a widely quoted order: Investigate suspicious intruders and shoot down hostiles “in a friendly sort of way.”

Attacks continued through the day. The penultimate victim crashed at 1:30 p.m. when Wasp’s fighter skipper Cleo Dobson received a vector from a radar controller. From 25,000 feet his wingman, Lt. (j.g.) M.J. Morrison, sighted a lone bogey 8,000 feet below. Dobson could not spot it so he ceded lead to the youngster. As the two Hellcats descended, he got a look at the dark-green intruder, a single-engine bomber. “Boy, he really made a splash,” Dobson wrote. “That was my first shot at a Jap in the air and I’ll tell you it really was a thrill.”

A half-hour later Ensign Clarence A. Moore of Belleau Wood won the race to the last kamikaze. It was another Judy, the 34th U.S. aerial victory of the day and the final kill of World War II.

Throughout the day Task Force 38 lost a dozen aircraft, with four Hellcat pilots killed and a Corsair pilot briefly captured.

Emperor Hirohito’s message was broadcast to the nation at noon. Thus, 70 million Japanese learned what most of the rest of the world already knew.

Many Japanese military men were astonished at the news. Navy Captain Minoru Genda, who had helped plan the Pearl Harbor attack, shared the opinion of many. He expected Japan to continue fighting indefinitely—as long as imperial warriors breathed.

Others were more outraged than awestruck.

Royal Navy Sub-Lt. Fred Hockley had bailed out of his Seafire that morning. Just 22, he was captured by civil authorities and turned over to the army. He was executed that night, several hours after Hirohito’s broadcast. Eventually two senior officers were hanged as war criminals.

In a dingy prison near Fukuoka, three hours after the emperor’s announcement, 17 B-29 crewmen were dragged from their cells and murdered in outrage over Hirohito’s capitulation. Most of the killers escaped the gallows owing to Douglas MacArthur’s postwar “big picture” philosophy.

Meanwhile, some senior Japanese naval leaders took their own lives. Vice Admiral Matome Ugaki, commanding the Fifth Air Fleet, felt he owed the emperor a death and resolved to fly the war’s last kamikaze mission. He squeezed into the rear seat of a Judy dive bomber alongside the radioman. Ten planes left Kyushu, Japan’s southern island, that afternoon though three returned with mechanical problems. Ugaki’s plane is thought to have crashed on an islet near Okinawa.

Ugaki’s friend, Vice Adm. Takijiro Onishi, had formed the Special Attack Corps in the Philippines in late 1944. He returned home to become vice chief of the navy general staff but sought atonement for the thousands of suicide aviators he had dispatched. He committed hara-kiri but botched the process and slowly bled to death the next morning.

Reflecting on events of the day, Halsey recorded: “I hope that history will remember that when hostilities ended, the capital of the Japanese Empire had just been bombed, strafed and rocketed by planes of the Third Fleet, and was about to be bombed, strafed and rocketed again. Last, I hope it will remember…the men on strike Able One [who] did not return.”

There were violent postscripts to the cease-fire. On the following two nights, Okinawa-based Northrop P-61 Black Widows intercepted two Japanese aircraft flying in violation of the cease-fire and destroyed both. Neither of the victories were credited because officially they occurred in peacetime.

On August 18 two Consolidated B-32 Dominators from the 312th Bomb Group were intercepted on a photo mission over Honshu. The Japanese navy fighters, led by ace Saburo Sakai, inflicted damage on one, wounding three crewmen, though both bombers returned to Okinawa. However, Sergeant Anthony Marchione of Pottstown, Pa., died of his injuries—the last American casualty of the war.

Thus ended World War II, a monstrous conflict whose sulfurous breath had seared four continents and claimed perhaps 60 million lives.

One fighter pilot spoke for all. Lieutenant (j.g.) Richard L. Newhafer—a future novelist and screenwriter—said the joyous news brought “all the hope and unreasoning happiness that salvation can bring.”

Frequent contributor Barrett Tillman is the author of nearly 900 articles and more than 40 books. For additional reading, try Tillman’s Whirlwind: The Air War Against Japan 1942–1945 and U.S. Navy Fighter Squadrons in World War II; Japanese Naval Aces and Fighter Units of World War II, by Ikuhiko Hata and Yasuho Izawa; and Last to Die, by Stephen Harding.

This feature originally appeared in the September 2020 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here!