AMONG THE TENS OF THOUSANDS OF DOGS that served in the Allied military during World War II, a few stand above all others for their acts of heroism. Chips was a German Shepherd mix who attacked an Italian machine gun nest on Sicily and helped capture 10 enemy soldiers. Caesar, a Marine Corps messenger dog, carried dispatches from HQ to the front lines and was seriously wounded by a Japanese sniper’s bullets. Gander was a Canadian Army dog who carried away a live grenade, saving a squad of soldiers at the cost of his own life.

At the apex of this elite group sits Judy, a white-and-brown English Pointer. She was a courageous and faithful companion, and the only official canine POW of the war. Given credit for saving the lives of many Allied soldiers and sailors, she proved to be the ultimate survivor under conditions that could only be described as horrific, imbuing the men around her with the hope and will to endure as well.

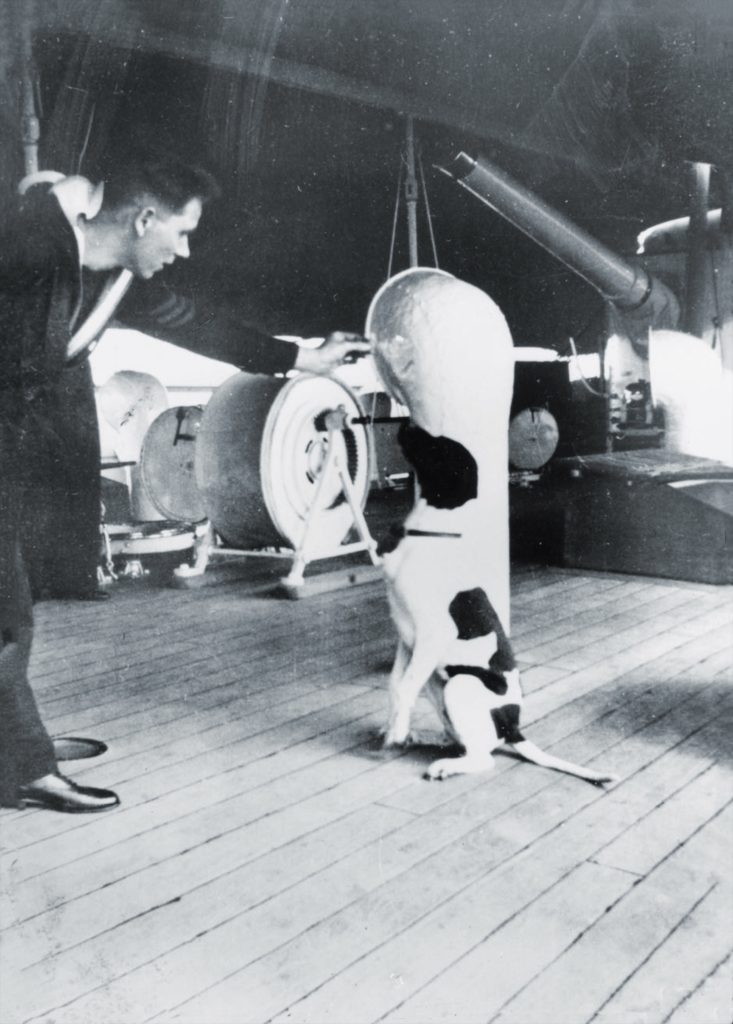

JUDY OF SUSSEX was born in February 1936 at the posh Shanghai Dog Kennels in that city’s International Settlement. She showed her proclivity for independence when, at just three months old, she burrowed under the compound’s chainlink fence and went feral, wandering about and foraging in one of Asia’s most frenzied cities. After a few weeks, one of the kennel workers discovered Judy and returned her home. Shortly afterward the men of HMS Gnat, a Royal Navy gunboat that patrolled the length of the great Yangtze River to keep the peace and control river pirates, adopted Judy as their official mascot. Judy immediately took to the crew, and they to her. Cared for by a succession of Royal Navy sailors, she reveled in the companionship they afforded.

In the days before ship-borne radar, Gnat was fortunate to have its own early warning device. Judy’s acute senses of smell, sight, and hearing, coupled with what one of her minders, Chief Petty Officer Charles Jefferey, called her “uncanny instinct for detecting threats,” would serve her and her shipmates well over the course of the coming war. This was amply demonstrated one night when pirates attacked the ship. The lookouts saw nothing, but Judy started barking loudly in the direction of oncoming boats. Rousted from their slumber, the British sailors defeated the raiders following a fierce gun battle. After that Judy became adept at sensing approaching enemy aircraft long before her human mates could, her noisy barks warning the crew of impending danger.

In June 1939 the Royal Navy transferred Judy and many of her shipmates to another gunboat, the newly built HMS Grasshopper, which soon joined the British fleet at Singapore. There the Grasshopper spent the next two years patrolling the seas between the great city-state and Hong Kong. Once war broke out in December 1941, the gunboats were ordered to Batavia, Dutch East Indies (now Jakarta, Indonesia). Grasshopper left Singapore with 200-some refugees, among them soldiers, nurses, and civilian mothers and their children. During the voyage Judy romped on the deck and played hide-and-go-seek with the kids, helping to keep spirits high.

On February 14, 1942, the gunboat was steaming past the Lingga Islands, 140 miles south of Singapore, when Japanese planes attacked it. A pair of bombs paralyzed the vessel, and its captain steered the ship toward uninhabited Posik Island, grounding it 100 yards off the beach. All crew and passengers safely reached land, but Judy was nowhere to be found. Her shipmates feared she had died below decks during the bombing.

The survivors soon realized the acute peril they were in—they had precious little food and no source of drinking water. Petty Officer George White volunteered to swim out to the still-smoldering Grasshopper to recover any food, water, and medical supplies he could find. As he moved around the boat, he heard an “unhuman sound, part whine, part moan.” He tracked the noise to a compartment amidships, and there he saw Judy trapped under a large steel locker. He freed the dog, and when she got to the beach she scampered around, greeting her many friends.

It wasn’t long before Judy noticed the lack of drinking water. She sniffed all around the ocean’s edge before settling on a small patch of sand, then began digging furiously, barking all the while. White went to investigate and as he approached, her paws exposed a bubbling spring of fresh water. “Water! Judy’s found water!” the sailor screamed.

After five days the ship’s captain was able to make contact with the residents of a nearby island. With their help, he secured a fishing boat with a Chinese crew to carry the party across to the east coast of Sumatra, where they were expecting British Army trucks to carry them to the port at Padang on the west coast—their only chance at escaping Japan’s inexorable advance as it approached through the Dutch East Indies. But when they arrived on Sumatra, they were told there were no trucks and, with Padang as their intended destination, they’d have to walk 170 miles through dense jungle to get there. In mid-February 1942 the group commenced its trek.

Judy seemed to take command of the march through the wilderness. As one of her minders, Les Searle, recalled, “She felt like the group ‘belonged to her.’ The way she acted was as though she was single-handedly responsible for their safe transit.” She adroitly guided them around marshes and over huge tree roots, all the while fighting off snakes and other menaces. On the second day the dog discovered a crocodile by the river’s edge. She moved in and started to bark. The croc took a swipe at her with his claw, opening a deep gash on her shoulder. Her bark immediately turned to a pained yelp as she backed away. Yet a few days later, Searle believed, Judy chased away a tiger that had been stalking the party.

It took a month for the refugees to reach Padang on March 16, 1942. Immediately looking for a ship to take them to safety, they were crushed to learn that the last one had left the port just the day before. The next day the roar of motorcycles announced the arrival of the Japanese army. The group had no choice but to surrender.

Their new home was an old Dutch army barracks on the outskirts of town that the Japanese had turned into a POW camp. Without enough food to go around, Judy took to hunting her own meals by crawling under the perimeter fence, much as she had done when escaping the kennels back in 1936. She became adept at catching rodents, birds, and reptiles, taking great risks with her nightly excursions as both her captors and the local natives had a predilection for dog meat. After a few months the Japanese moved half of the Allied POWs to Gloegoer prisoner camp at Medan, 330 miles northwest of Padang in northern Sumatra. Judy’s minders wrapped her in a gunnysack and smuggled her aboard one of the trucks.

WHILE JUDY HAD ALWAYS been completely dedicated to the many Royal Navy sailors on both Gnat and Grasshopper who had looked after her, she always seemed to be searching for a single human companion she could trust implicitly. In Medan she found such a fellow—Leading Aircraftman Frank Williams, a 22-year-old electronics technician with the Royal Air Force. A lanky, gentle man with wavy brown hair and a kind face, he had wanted to be a pilot but was too tall, so he settled on becoming a radar expert. His journey from Padang to Medan paralleled Judy’s, though the two had never met.

That changed one day when Williams was eating his daily rice ration and noticed a dog staring at him. Judy eyed the newcomer warily, then began walking toward him. She stopped a few feet away, sat, sniffed the air, cocked her head, and watched him closely. Williams scooped out a handful of rice and offered it to her. Still, she remained seated. He then offered her his entire ration. She moved closer, and as he “scritched” her ears she ate hungrily. She then curled up at his feet. “I remember thinking what on earth is a beautiful English Pointer like this doing here with no one to care for her,” he recalled. “I realized that she was a survivor.” After that the two were inseparable.

The POWs fell into a new routine at Medan. Working parties were sent out each day to finish the disassembly of a local industrial plant. Judy often went along until her run-ins with the Korean guards reached a dangerous level. She hated her captors and let them know it in no uncertain terms. Her snarling provoked them into trying to attack her with the butts of their rifles. More than once their blows hit home. Finally, Williams decided to lock her up at the camp to keep her safe.

It was then, early in 1943, that Williams hit upon an idea to help shield his companion from overaggressive guards: he decided to have her officially added to the list of POWs. With trepidation he approached the camp commandant, Colonel Hirateru Banno, intent upon getting him drunk and plying him with the presentation of a puppy from Judy’s recent litter. To Williams’s surprise the colonel was amenable and wrote an order declaring the dog as “prisoner number 81A Gloegoer-Medan.” And thus Judy of Sussex became World War II’s first and only official canine prisoner of war.

In June 1944 the Japanese announced that all POWs were to be shipped to Singapore. All but Judy. When the new commandant, Captain Nissi, first met the dog, he took an instant dislike to her. As the time approached to board the ship, he made it clear that Judy had to stay behind. So Williams devised a scheme to circumvent the officer’s order—he would carry her aboard in an empty rice bag. He spent hours training her to lay silent and stock-still in the bag. The ruse worked, and when the old Dutch freighter SS Van Waerwijck steamed out of Medan’s port carrying 700 POWs, dog and man were still together.

The Japanese had converted the vessel to carry prisoners by building racks of bamboo sleeping platforms in the dank, smelly hold. Just two days after sailing, a pair of torpedoes, fired by the British submarine HMS Truculent, slammed into the side of Van Waerwijck, tearing a huge hole that quickly flooded the below-decks compartments. Williams pushed Judy out through a porthole and into the churning sea. He followed, but in the chaos quickly lost track of her.

Williams was pulled from the water by a Japanese tanker and sent with other POWs to a prison camp near Singapore. Along the way he started hearing stories about a dog that had rescued survivors of the attack, and he knew that dog was Judy. Les Searle recalled that Judy had pushed floating debris toward men in the water and even let a few hang onto her back while she dog-paddled toward a local fishing boat picking up men. He remembered thinking, “Why didn’t the poor bitch shake [them] off, save herself?” Searle carried the oil-covered heroine ashore and hid her in one of the trucks headed to the prison camp, arriving a couple of days before Williams. When they got there, Judy went looking for Williams, combing every corner of the camp but turning up nothing. So she waited at the main gate for him to come. When he did, she knocked him to the ground and licked his face while he hugged her madly.

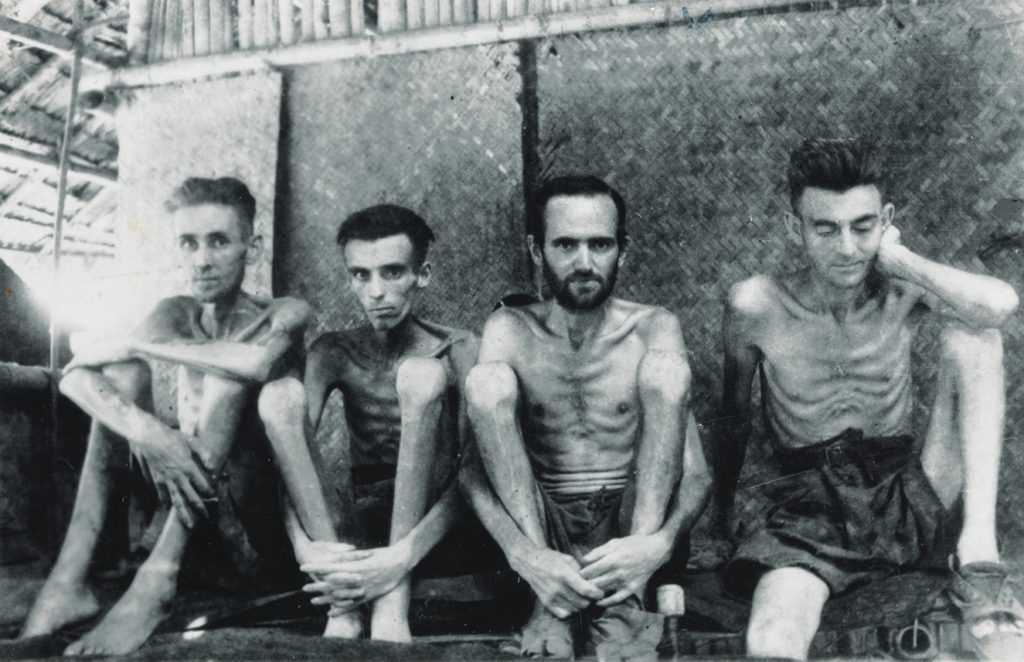

In late summer 1944 the Japanese army moved the Allied prisoners for the last time, assigning them to join in the effort to complete a 300-mile railway line through central Sumatra. Camp facilities were next to nonexistent, with food rations cut below subsistence level. Incidences of tropical diseases, like malaria and beriberi, rose at an alarming rate. Men began to die—sometimes as many as 10 a day. Like most of his compatriots, Frank Williams was no more than a skeleton. And Judy was not much better off. Writing after the war, Williams said, “She wasn’t that tame, obedient dog anymore. She was a skinny animal that kept herself alive through cunning and instinct.” Through it all the pair remained inseparable. “All I had to do was look at her and into those weary, bloodshot eyes, and I would ask myself: ‘What would happen to her if I died?’” Her survival became the driving force in his life.

After Japan surrendered in August 1945, British Army paratroopers went into the camps to liberate all the POWs. And then the long journey home began, though not without a major hitch: Judy was denied passage aboard the homebound troopship. But, once again, her friends smuggled her aboard and kept her well-hidden. Her survival story began circulating around the ship, and even before the POWs landed, the English media was onto the story. This caught the attention of a British veterinary charity, the People’s Dispensary for Sick Animals (PDSA).

When the POWs arrived at Liverpool, health authorities quarantined Judy for six months. It was the first extended period Frank and Judy had been apart since they met, and neither took it well. On April 29, 1946, Judy was finally released from quarantine, and the PDSA awarded her the Dickin Medal, the animal equivalent of Britain’s highest military honor, the Victoria Cross (equivalent to the U.S. Medal of Honor). Her citation reads: “For magnificent courage and endurance in Japanese prison camps, which helped to maintain morale among her fellow prisoners and also saving many lives through her intelligence and watchfulness.”

Judy became a media hit. “Gunboat Judy Saves Lives—Wins Medal and Life Pension,” a headline in the Daily Mirror blared. She and Frank Williams were feted around the nation, making tours of children’s hospitals and rehabilitation centers. During these events Judy wore a specially tailored RAF jacket with her campaign ribbons adorning her collar.

STIFLED BY the constrictions of life in postwar England, in 1948 Williams took a job in East Africa, both he and Judy settling down in southern Tanzania. It was a wonderful experience for the pair. Judy went on safari in the scrublands, battling with snakes and other wild critters just as she had done in Sumatra. In early 1950 she went missing for nine days. When Williams found her, she was seriously ill, and a doctor at the local hospital diagnosed a tumor. He operated right away, but an infection overwhelmed her body. On February 17, Williams was forced to euthanize Judy. She was buried in her RAF jacket underneath a marble memorial Williams built near his home.

Down the mighty Yangtze, around the verdant Lingga Islands, across the dense jungles of Sumatra, Judy of Sussex, POW 81A Gloegoer-Medan, loyally, and often at great risk to herself, saved lives and inspired the belief among her fellow prisoners that survival, though difficult, was indeed possible—as she had proved time and again throughout her resilient life. Now, eight decades on, the enduring memory of her exploits is kept alive in books, magazines, and online articles. And every year a few hearty souls make the long trek to Judy’s gravesite in Nachingwea, Tanzania, to pay tribute to one of the most storied dogs of her generation. ✯

This article was published in the October 2021 issue of World War II.