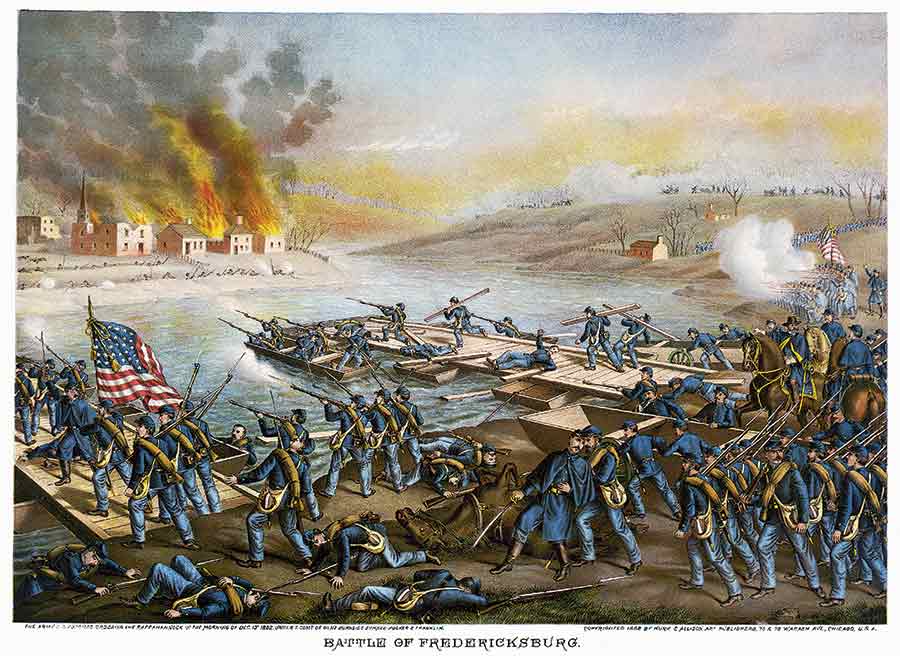

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]“Bring the guns to bear and shell them out.”[/quote] It was a command Union Brig. Gen. Henry J. Hunt probably hoped he wouldn’t have to give. But on December 11, 1862, after a series of aborted attempts by the Federals to cross the Rappahannock River into Fredericksburg, Va., the Army of the Potomac’s chief of artillery was given little choice. It was time for Hunt’s big guns to “batter” the bucolic colonial town into submission. For the first time, not an army but an American city itself would be the target of bombardment by the U.S. military.

Built in 1727, Fredericksburg had a storied history, a profitable tobacco town in its early days and onetime home to the likes of George Washington, James Monroe, and John Paul Jones. Located roughly halfway between Richmond and Washington, D.C., it had become a prosperous mill town by the Civil War, with more than 5,000 residents, including a sizable population of both slaves and free blacks.

By the end of Hunt’s relentless artillery barrage on December 11, Fredericksburg’s once-majestic homes and buildings were wrecked, many nearly beyond recognition. That was tragic enough, but what happened next would, in the words of historian Donald Pfanz, go down as “the most disgraceful episode in the Army of the Potomac’s history.”

In the fall of 1862, following its September victory at Antietam, the Army of the Potomac had again turned its attention to the capture of the Confederate capital of Richmond. To do so, the army’s newly named commander, Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside, determined his best option would be to pass through Fredericksburg. After taking command from Maj. Gen. George McClellan on November 7, Burnside moved his forces with impressive—and uncharacteristic—speed from their bases in northern Virginia to Falmouth, opposite Fredericksburg on the northern side of the Rappahannock. A railroad bridge over the river had been destroyed, so Burnside decided to cross into Fredericksburg on pontoon bridges to be built at several key locations. The 38-year-old West Pointer did not intend to fight in the city. Rather, he hoped to use it as a rear supply base as he moved against Richmond.

Fredericksburg was not considered a vital military target for either army and was lightly defended when the first of Burnside’s men reached Falmouth on November 17. The Federals, however, would be stranded waiting for the pontoon boats to arrive from Washington, and by then it was too late. General Robert E. Lee had felt sure the Union army would likely use one of four routes to attack the capital, and when he finally realized Burnside’s intentions, he wasted no time rushing James Longstreet’s First Corps and Stonewall Jackson’s Second Corps to Fredericksburg from Culpeper, Va., and the Shenandoah Valley, respectively.

It will never be known how the war would have unfolded had the Army of the Potomac been able to cross the river when it first arrived, but Burnside soon realized he had lost any element of surprise. As Lee’s men arrived and quickly established heavily fortified positions across the river, Union morale began to sink, and periods of freezing rain and cold did not help. Most of the Federals fathomed that the suddenly strong Confederate presence in the town meant an invasion was likely a suicide mission. One soldier captured that mood in a letter home: “It looks to me as if we were going over there to be murdered.”

The entire contingent of pontoon boats finally arrived on November 27—10 days too late—and Burnside and his subordinates began considering alternative plans. Ultimately, the decision was made to send across two of his three grand divisions: one on the right and one on the left, while keeping the one in the center in reserve. Early in the morning of December 11, men from the 50th and 15th New York Engineers began laying six pontoon bridges across the river, seemingly unaware of just how formidable the Confederate defenses were. A Mississippi brigade of 1,600 men, commanded by Brig. Gen. William Barksdale, had built a strong line of defenses in the houses opposite one of the bridges. Working primarily at night, the Rebels had quietly dug rifle pits, with zigzag trenches connecting them to holes chopped in cellar walls, enabling men to move from one house to another without detection.

Barksdale’s men watched Yankee bands gather on their side of the river one night to play patriotic songs, including “The Star-Spangled Banner.” They remained quiet until the Union bands began to play “Dixie,” at which point the men on both sides started laughing, cheering, and singing along together. To Lee and his commanders, it was a sign the Federals were about to attack across the river. Barksdale was ordered to dig more trenches. If Burnside indeed intended to lay a bridge opposite Barksdale’s position, his engineers—working in the open with their hands full of hammers, planks, and heavy beams—could be easily picked off.

A heavy fog initially provided protection for the 50th New York, commanded by Major Ira Spaulding. At first, Barksdale’s Mississippians fired blindly into the fog, with sporadic, though unnerving, success. But it wasn’t long before Southern sharpshooters began to find their targets and disrupt the proceedings. Spaulding’s engineers attempted to complete the work on at least nine occasions, only to come under relentless fire each time. The Union commanders finally agreed that no one could survive out in the open. Although two bridges had been erected south of town, there was no way bridges could be built in the other locations.

By 12:30 p.m., Burnside decided an artillery barrage on the town was his only recourse. Hunt had nearly 150 guns well-positioned on Stafford Heights overlooking Fredericksburg. They were soon firing away furiously.

The barrage continued for roughly two hours. A member of the 5th U.S. Artillery claimed his four 20-pounder Parrotts fired 500 rounds, though the average tally per unit was about 50 rounds. “[T]he earth shook beneath the terrible explosions of the shells, which went howling over the river, crashing into the houses, battering down walls, splintering doors, ripping up floors,” one Northern reporter wrote. Union nurse Clara Barton watched in horror from the Army of the Potomac’s headquarters on Stafford Heights, seeing “roofs collapse, walls and chimneys cave in, buildings blow apart, timbers and bricks explode through the air, and houses burst into flame.”

One Ohio soldier probably put it best: “Talk of Jove’s thunder. Had the ancients heard so frightful and so incessant a noise they would have sunk into the ground in terror.”

Warned ahead of time about the pending danger, most residents had fled the town well before December 11, but a few remained or returned when an attack no longer seemed imminent. Four of that lot were reportedly killed during the shelling; the rest had bolted for their cellars as fast as they could. In her diary, Jane Beale described the terror of seeing a cannonball strike a glancing blow to the head of her 10-year-old son: “I soon saw that there was no terrible wound, only a deep redness of the skin about the shoulder and breast.” She noted that, though he had survived, he felt weak and was hurting for a while.

Frances Bernard’s mother rushed upstairs to save a portrait of her late husband that was hanging over the sofa. Just as she pulled it down and headed back to the cellar, a Union shell came crashing through the wall, demolishing the sofa and most of the living room.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]Burnside’s engineers—working in the open with hammers, planks, and heavy beams—could be easily picked off[/quote]

Longstreet later described the bombardment as “a scene which can never be effaced from the memory of those who saw it.” Lee also watched from a nearby hill, growing increasingly angry. “Those people,” he said derisively, using his favorite term for Yankees, “delight to destroy the weak and those who can make no defense; it just suits them!”

What Burnside and Hunt soon discovered is a reality many military leaders have learned over time. Such bombardments often don’t work. Although the houses in which Barksdale’s troops were safely hidden had been razed, the cellars, rifle pits, and trenches remained largely intact, and only a few of his men had been wounded. The relentless shelling had made it no easier for the Federals to cross the river.

At one point, Lee sent a courier to Barksdale to find out if his Mississippians were all right. Replied Barksdale: “Tell General Lee that if he wants a bridge full of dead Yankees I can furnish him with one.”

When the barrage stopped about 2:30 p.m., the Union engineers ventured out on the bridge again, cautiously optimistic the shelling had succeeded. Barksdale’s men opened fire immediately, killing some while the others scrambled back to safety. The suggestion was made and approved by Burnside to send troops over in a boat about a mile upriver to establish a beachhead north of town. The task went to the 7th Michigan and the 19th and 20th Massachusetts.

The beachhead in place, the Federals went after Barksdale’s Brigade, battling street to street and house to house with considerable bloodshed. It took more than an hour to push the Rebels back a single block, but the Union engineers were able to complete their contested pontoon bridge, allowing other troops to cross and drive the enemy farther back through town.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]The relentless shelling had made it no easier for the federals to cross the river[/quote]

But there were still dangers. As Clara Barton walked across the bridge on her way to treat the wounded, she noticed “the water hissing with shot on either side.” And the soldiers’ declining morale was not helped by the sight of an enterprising undertaker near the bridge offering his business cards to the troops. He was quickly sent packing.

The more religious soldiers tossed away their decks of playing cards as they made their way across the river. Since they believed that gambling was a sin, Donald Pfanz would write, “no soldier wanted to face his Maker with a deck of cards in his pocket.”

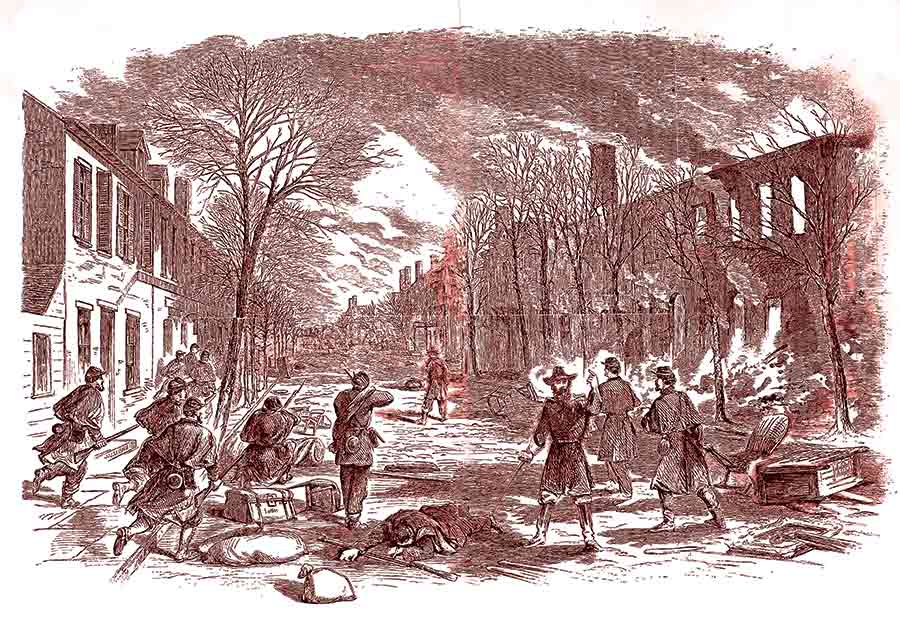

Finally, all six bridges were completed and the men of the Army of the Potomac—bitter, angry, and resentful—began occupying the damaged town. According to historian Nancy Baxter: “They were demoralized. They had lost too much, too often; their energies had turned sour, passing from cider to vinegar in three months’ time. They were lawless and on the rampage like a gang of tough boys who find the soda shop closed and go to smashing windows. Their bitterness was also increased by one final realization: the knowledge gradually dawning that the Northern position in the battle tomorrow was probably hopeless.”

Recalled Brig. Gen. Marsena Patrick, the army’s provost marshal: “When I went into town, a horrible sight presented itself….The soldiery were sacking the town! Every house and store was being gutted! Men with all sorts of utensils and furniture, all sorts of eatables and drinkables and wearables, were [being] carried off.”

Not one building in the town remained untouched. Even Bibles and communion sets were stolen from the various churches.

Patrick had no hope of stopping the looting and destruction. It was on too vast a scale for the small number of men under his command. The best he could do was to set up guards at the bridge to prevent the men from taking their loot back to camp. Within a short time, the items confiscated ranged from whiskey to food, women’s clothing, and a grand piano.

The Yankees apparently stole whatever they could carry and wrecked everything else. Many were drunk, but others were sober enough to search for jewelry and other valuables in the houses and shops, and to blow up bank safes and steal the money. One man boasted of pilfering 37 watches.

One group entered a house where a soldier stopped to play a song on the piano. When he finished, the others raised their muskets and smashed the keyboard. Others carried pianos out into the streets, then broke them into piles of kindling and lit bonfires. They stole enough food for a feast, better than they had eaten in a long time. What they did not consume they left to rot in the gutters.

Books, furniture, elegant crystal glasses, and fine paintings were tossed from windows, family portraits slashed with bayonets, mirrors smashed to bits. Clothing was put on over uniforms to be worn as trophies. Army canteens were emptied of water and filled with whiskey and wine.

The rampaging Northerners pried open barrels of flour and molasses, poured them out and smeared them into fine carpets. One unit dragged nearly a hundred mattresses out into the streets, arranged them in formation and bedded down, enjoying a night of not sleeping in the mud.

A reporter for the Boston Journal, Charles Coffin, called it “a carnival night,” and Major Francis Pierce of the 108th New York Infantry described how “splendid alabaster vases and pieces of statuary were thrown at six and seven hundred dollar mirrors. Closets of the very finest china were broken into and their contents smashed onto the floor and stomped to pieces. Finest cut glassware goblets were hurled at nice plate glass windows….The soldiers seemed to delight in destroying everything.”

The ensuing Battle of Fredericksburg on December 13 would prove yet another low point for the Army of the Potomac in a year mired with battlefield misfortune. The Federals had more than 100,000 men engaged and suffered an estimated 13,353 casualties. On the Confederate side, there were 4,576 Confederate casualties out of 72,500 engaged.

Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtin, who witnessed the carnage, later told President Abraham Lincoln that “it was not a battle, it was a butchery.” When Lincoln heard what had happened, he fell into despair and remarked, “If there is a worse place than Hell, I am in it.”

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]’It was ‘the most infamous crime ever perpetrated upon this continent’ Richmond Daily-Dispatch[/quote]

The Union survivors retreated from Fredericksburg on the night of December 15, marching back over the bridges they had built. Two days later, the residents streamed back into town to see what was left. Among them was Lieutenant Charles Minor Blackford, checking on his mother’s house, where he had grown up. The structure had been thoroughly wrecked, room by room, and then used as a makeshift

hospital. In the attic, Blackford found several generations of his family’s letters, which had been stored in huge barrels, strewn over the floors and into the yard. Many had been ripped to shreds. “In the dining room the huge table was used as an operating table and a small table by its side had a pile of legs and arms upon it….The whole house was covered with mud and blood and it was hard to realize that it was the dear old house of my childhood.”

When Fanny White returned to her home, she found one of the rooms “piled more than halfway to the ceiling with feathers from beds ripped open, every mirror had been run through with a bayonet, a panel of each door cut out, furniture nearly all broken up, the china broken to bits, and everything of value taken away.”

Fredericksburg lay in ruins, with only chimneys and remnants of walls still standing amid rubble-strewn streets. Even the few buildings that remained standing were battle-scarred and damaged, some far beyond repair. Many of the residents found they were financially ruined. Wealthy families became paupers, with their homes and businesses destroyed and no assets to rebuild and replace what they had lost. Homeless women and children faced starvation. It was “the most infamous crime ever perpetrated upon this continent,” the Richmond Daily-Dispatch would soon claim.

Stonewall Jackson was apparently so upset at the plight of the refugees and the ruined town that he urged his men to take up a collection to help them. The soldiers, many of whom had no shoes or winter clothing, raised the sum of $1,371—a staggering amount especially from those with so little themselves. When word of the destitution spread throughout the South, people contributed trainloads of food and clothing for shipment to Fredericksburg, along with $170,000 in cash.

Southern citizens and soldiers alike were shocked and angered when news spread of the destruction of Fredericksburg. “I hate them worse than ever,” one Confederate soldier wrote home, “and then their destruction of poor old Fredericksburg! It seems to be that I don’t do anything from morning to night but hate them worse and worse.”

Some inhabitants found consolation in the ghastly sight of the massive number of Union dead. One local shop owner wrote: “But for all this loss, [we] feel ourselves amply repaid when [we] viewed the thousands of the enemy’s corpses upon the battlefield.”

The marks of destruction remained long after the battle. Nearly a year later, perhaps only about 800 of the town’s inhabitants had returned, and ruins remained visible well after the war ended in 1865.

One other bitter memory remained in the minds of the citizens of Fredericksburg. The day after the Union troops retreated, Confederate soldiers returned to the devastated town and some of them looted houses and shops. One resident feared that “the Rebels would likely take whatever the Yankees had left behind.” And a dispirited employee at a local bank, who had lost his home and business, wrote sadly, “It is, as you know, the fate of war.”

Duane Schultz has written numerous articles and books on military history, including The Dahlgren Affair: Terror and Conspiracy in the Civil War and The Fate of War: Fredericksburg, 1862.