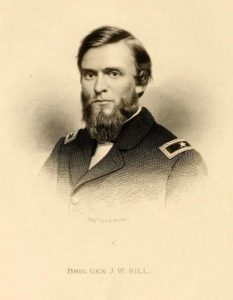

“Another sacrifice to the grim, insatiate Moloch of War,” The Highland Weekly News evoked when it reported the untimely death of Brig. Gen. Joshua W. Sill in its January 22, 1863, edition. “Gen. Sill was well known and everywhere admired throughout Ohio…..He falls lamented by an admiring State and grateful country, in whose memory and history he will be forever cherished.”

Today, Sill’s service and sacrifice are memorialized at two locations more than 1,000 miles apart. One is his namesake U.S. Army post—Fort Sill, Oklahoma. The other is a marble and limestone monument at his gravesite in Chillicothe, Ohio. While one remains a thriving, bustling training center with thousands of troops at the largest artillery installation in the world, Sill’s rapidly deteriorating gravesite monument is threatened with destruction.

Born in Chillicothe on December 6, 1831, Joshua Woodrow Sill received an appointment to the U.S. Military Academy from Ohio Whig congressman John L. Taylor in 1849. He excelled as a cadet, graduating third in the Class of 1853 and was commissioned in the Ordnance branch. While a West Point cadet, he had roomed for a time with Phil Sheridan, and the two became lifelong friends. From 1853 to January 1861, Sill served ordnance assignments at the Watervliet Arsenal (twice), the Pittsburgh Arsenal, and did a two-year tour (1855-57) at West Point as an instructor of cadets. In January 1861, Sill resigned his Army commission and began a civilian teaching job as a professor of Mathematics and Civil Engineering at the Collegiate and Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn in New York.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]”Gen. Sill is lamented by an admiring State and grateful country.”[/quote] When the war broke out in April 1861, however, he patriotically returned to the colors, resigning his academic position and offering his service to Ohio Governor William Dennison. In May, the governor appointed Sill assistant adjutant general of the state with the primary duty of organizing the formation of Ohio volunteer regiments and preparing them for Union Army service. In August 1861, Sill was commissioned colonel of the 33rd Ohio Infantry and led it that fall to join Union forces in eastern Kentucky.

Sill established a solid reputation as a humble and modest officer and a brave and resourceful battlefield commander. His men adored him. An officer recalled that the soldiers “fairly worshipped him, for he treated them like men.” One of his officers stated that “No man in this entire army, as I believe, was so much admired, respected and beloved by inferiors and superiors in rank as was General Sill.” Sill rose from colonel of the 33rd Ohio to brigadier general on July 16, 1862.

At his request, Sill received command of the 1st Brigade in his old West Point friend Brig. Gen. Phil Sheridan’s 3rd Division in the Right Wing of Maj. Gen. William Rosecrans’ Army of the Cumberland. At the Battle of Stones River on December 31, 1862, a Confederate musket ball struck the 31-year-old Sill in the face and penetrated his brain, killing him. Sill was one of Sheridan’s four brigade commanders struck down that day—based on number of casualties as a percentage of troops involved (nearly 33 percent) the bloodiest major battle of the war. Sheridan expressed that Sill’s death, “abruptly closed a career which, had it been prolonged a little more, not only would have shed additional lustre on his name, but would have been of marked benefit to his country.”

Sill’s body fell into enemy hands and he was initially buried in a battlefield cemetery. However, a committee of citizens from his hometown, Chillicothe, Ohio, went south and retrieved it for reburial. His remains—transported by a hearse from the church to Grandview Cemetery and escorted by a band, relatives and friends, army officers and soldiers, the mayor, and city officials—were reinterred in early February 1863. A fluted column, broken below its capital, and draped with the American flag, was erected over his gravesite. Nearly a century later, on Memorial Day 1957, a bronze plaque donated by the officers and soldiers of Fort Sill, Oklahoma, Sill’s namesake army post was added to the monument.

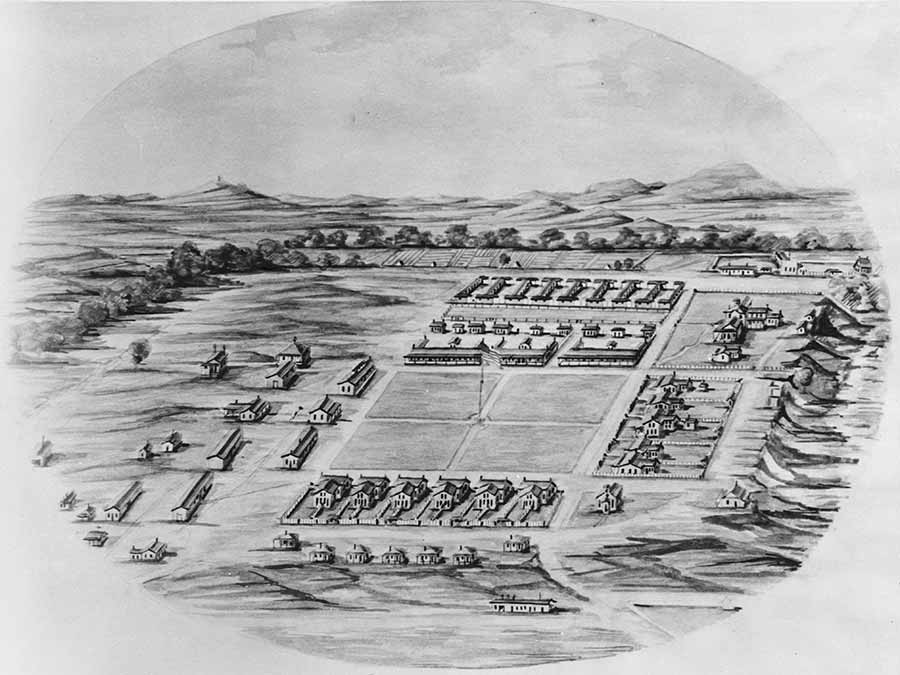

In January 1869, Sheridan, at that time commanding frontier army forces operating against hostile Indian tribes, memorialized his fallen friend by renaming Camp Wichita, Indian Territory (80 miles south of present-day Oklahoma City) “Fort Sill” in his memory. Much of the original construction of the fort’s buildings was done by 10th Cavalry Regiment “Buffalo Soldiers” under the command of Colonel (Brevet Maj. Gen.) Benjamin H. Grierson, who in 1863 had led “Grierson’s Raid” during Grant’s Vicksburg Campaign. Fort Sill was an important post during the Indian Wars, including the location where the Army held Apache prisoners of war, notably Geronimo.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]The soldiers “fairly worshipped him, for he treated them like men.”[/quote]

The number of well-known Native Americans buried in Fort Sill cemeteries has earned it the nickname “The Indian Arlington.” In 1911, the U.S. Army Field Artillery School (then known as the School of Fire for Artillery) was established there, and Fort Sill has become the premier artillery (field artillery and air defense artillery) complex in the world, training artillerists from the U.S. Army and Marine Corps as well as those of international Allied nations. Through his namesake “Fort Sill,” the Sill moniker quite literally is known throughout the world. Yet secure and lasting fame is definitely not enjoyed by Sill’s Chillicothe monument.

Sill’s monument in Chillicothe’s Grand View Cemetery, meant to stand in perpetuity, might not last much longer unless serious action is taken. The base holding the monument is in poor condition and unstable. The monument—made of marble and limestone—is caked with biological growth and the epitaph is faded. The bronze plaque added in 1957 also badly needs to be restored.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]Sill’s monument, meant to stand in perpetuity, might not last longer.[/quote]

The Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War (SUVCW), Sergeant Richard Enderlin Camp #73—the organization that initiated the project—and the Chillicothe-Ross Community Foundation are trying to raise enough funds to restore the monument. They have a bid from the Columbus Art Memorial, Inc.—a family-owned business, founded more than 90 years ago—for $32,000 to take on the project. The fee will cover the expense of dismantling the monument, transporting it to Columbus for restoration, and returning it to the cemetery. The project will take 6–8 months to complete. The company’s past restoration projects include the Medal of Honor Grove at Valley Forge, Pa.; the Columbus, Gahanna, Groveport, and Grove City police memorials; and the Christopher Columbus (Columbus State Community College) and Johann Christoph Friedrich von Schiller statues (Schiller Park, Columbus, Ohio).

The best way to donate is through the General Sill Monument GoFundMe page. Every tax-deductible donation counts.

Frank Jastrzembski, who writes from Cleveland, Ohio, is a regular contributor to America’s Civil War.