The Union colonel’s own clouded hindsight has led to confusion about his 1864 heroics.

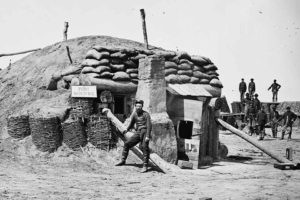

June 18, 1864 was not a good day for the Army of the Potomac. Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant had ordered another series of assaults against the Confederate lines at Petersburg, Va., hoping to capture the city before General Robert E. Lee could fully reinforce the thinly held Confederate trenches.

Grant had about 67,000 men at his disposal to 20,000 for the Rebels, but confusion, miscommunication, and the Confederates’ adept juggling of reinforcements doomed the Union onslaughts. Rank after rank of blue troops faltered under withering gunfire. The Second Battle of Petersburg, which had opened on June 15, would end in Northern defeat and the beginning of a protracted siege that would last for months.

Joining the June 18 attacks, on the far left of the Union lines in Brig. Gen. Charles Griffin’s 1st Division of Maj. Gen. Gouverneur Warren’s 5th Corps, was a brigade of Pennsylvania regiments under Colonel Joshua Chamberlain—the 121st, 142nd, 143rd, 149th, 150th, and 187th. Chamberlain was already famous in the Army of the Potomac for his Little Round Top heroics at Gettysburg the previous July, and when he returned to active duty in April 1864 after an extended illness, he was given command of the Keystone State regiments.

As the brigade struggled ahead, its standard-bearer went down with a wound. Chamberlain grabbed the banner and, as he urged his men forward, a Minié ball slammed into his pelvis. “I was standing so firmly on the ground at the time that I did not fall at first,” Chamberlain recalled. “I thrust the point of my sword into the ground and balanced myself over the hilt and held myself in that position until the men of the first line had passed in charge. I knew that if they saw their leader fall it would discourage them, so with rigid features I held myself up although helpless in all other ways. They saw me standing there like a statue leaning on my sword, but did not dream that I had received a mortal wound….”

When Grant heard of the colonel’s grievous wound, he promoted Chamberlain to Brigadier General on June 20. Chamberlain’s gallantry is undisputed. There are, however, two competing views on the location of the June 18 attack that nearly killed him. While the charge occurred near where the Baxter Road wound its way through the Confederate earthworks near Pegram’s (or Elliott’s) Salient, many histories of that day’s fighting place his charge and horrible wounding farther to the south near Rives’ Salient, not far from the Jerusalem Plank Road. Where did that second interpretation come from? From Chamberlain himself, it turns out—presenting an interesting case study of how cloudy memory can impact history.

[dropcap]C[/dropcap]hamberlain had recalled the events 35 years after the attack, in an 1899 memoir The Charge at Fort Hell. Interestingly, the actual text of Chamberlain’s manuscript makes no specific reference to Rives’ Salient, Fort Sedgwick, or “Fort Hell”; only the title alludes to this location. Chamberlain claimed his brigade charged and carried the position that subsequently became Fort Sedgwick, also known as “Fort Hell,” after which the brigade advanced from the south along the Jerusalem Plank Road against the permanent Confederate works at Rives’ Salient, under murderous enfilading fire from Fort Mahone to the west. But Fort Sedgwick did not exist when Chamberlain made his famous charge. Perhaps he was confused, or perhaps his intent was to offer a general point of reference with which others could connect, given the site’s subsequent notoriety.

Chamberlain’s other speeches and writings during the final years of his life linked his charge with Fort Hell. Then a series of Chamberlain biographers picked up on his lead, embracing the viewpoint in writings spanning more than half of a century, including but not limited to Willard M. Wallace (Soul of the Lion: A Biography of General Joshua L. Chamberlain, 1995); Alice Raines Trulock (In the Hands of Providence: Joshua L. Chamberlain & the American Civil War, 1992); Mark Nesbitt (Through Blood and Fire: Selected Civil War Papers of Major General Joshua Chamberlain, 1996); Edward G. Longacre (Joshua Chamberlain: The Soldier and the Man, 1999); and Diane M. Smith (Chamberlain at Petersburg: The Charge at Fort Hell, 2004).

With the exception of Smith’s book, the authors dedicated only a few pages to Chamberlain’s experience at Petersburg on June 18, 1864. Smith’s book is entirely devoted to the June 18 attack, and she based her book on the 1899 The Charge at Fort Hell, which had remained unpublished and largely forgotten in the Special Collections Library at Duke University until 2004. Smith’s extensive annotations and the fact that it purports to present an accurate account from Chamberlain’s pen gives Chamberlain at Petersburg an aura of authority that has influenced the historical record. Numerous websites, for example, promote as historical fact the idea that he was wounded near Rives’ Salient, including the National Park Service’s website for Petersburg National Battlefield, which is perplexing since other NPS documents support the Baxter Road site.

Chamberlain was so badly injured that he did not leave a contemporaneous account of his movements or activities on June 18. The only official report of the action of Chamberlain’s 1st Brigade comes from Colonel William S. Tilton, who assumed command of the unit on the evening of June 18, and Chamberlain himself did not discuss his whereabouts at Petersburg that day for nearly two decades. He apparently did not revisit the battlefield until January 1882, while returning from a winter trip to Florida. He recorded his impressions in a letter to his sister, penned January 29.

In that account, he described having spent four hours trying to identify the spot where he had fallen while leading his charge against the Rebel works. “All is changed there now,” he wrote. “What was a solid piece of woods through which I led my troops is now all cleared field, & the hillside so smooth there is now grown up with little clumps of trees….At last, guided by the [Norfolk & Petersburg] railroad cut & the well-remembered direction of the church spires of the city, I found the spot—or a space of 20–30 feet within which I must have fallen….I looked down & saw a bullet, & while stooping to pick it up, another & another appeared in sight & I took up six within as many feet of each other and of the spot where I fell.”

Because of his unfamiliarity with features of the topography, Chamberlain resorted to using the railroad cut and Petersburg’s church spires to lead him to the spot where he fell. But the steeples are perhaps two miles from Chamberlain’s supposed Rives’ Salient attack position, and a mile and a half from the Baxter Road position.

The similarity of perspective between the two sites, which are both southeast of the town, makes it difficult to fathom how he could achieve accuracy in pinpointing a precise location based on the distant landmarks.

In September 1900, Chamberlain was featured in an article in a local Maine newspaper, the Lewiston Evening Journal. In it, Chamberlain provided his most detailed recounting of the events that had transpired 36 years earlier. It is important to reproduce it nearly in its entirety in order to fully understand this critical event and his memory of it:

“During that summer, I had been assigned to a splendid brigade of six regiments, and on the morning of the 18th, I charged with this force and carried the enemy’s advanced position in front of Petersburg, known as “Fort Hell.” There I had three batteries sent to me to hold my position, which was in close proximity to Rieeves’ [sic] Salient, so called, [which] was the enemy’s main entrenched line….With this force, I was more than a mile in advance of our army on the extreme right [sic]. At this moment, an aide dashed up and gave me a verbal order from the commanding general to charge and carry the enemy’s main works in my front.

To say that I was astonished would be putting it mildly. I couldn’t believe it possible that they meant for me to do this with only one brigade….I immediately drew my note book and wrote a letter to the commanding general, stating the situation and asking if there was a mistake in the order to charge. I gave this note to the aide and told him to carry it to General Grant at once, which he did. It was an audacious thing for me to do, and after the message was gone, I began to realize that I had risked my shoulder straps. It was a virtual disobedience of orders to attack an enemy, which under any circumstances is a hazardous thing to do. I expected to be placed under arrest at once, so I communicated to my subordinate officers informing them of my probable immediate arrest and removal….

In a short time, the staff officer who had taken my message to the general commanding the army returned. Instead of placing me under arrest, as I expected, he said that the general approved my course and the advice contained in my message. He also said the whole army would attack at once, but from my advanced position, it would be necessary for me to lead the assault. He asked when I would be able to attack, and I replied: At one o’clock.”

Chamberlain still had a copy of the letter he wrote to Grant, and transcribed it in entirety for the newspaper:

“Lines Before Petersburg, June 18, 1864, I have just received a verbal order not through the usual channels, but by a staff-officer unknown to me, purporting to come from the General commanding the Army, directing me to assault the main works of the enemy in my front.

Circumstances lead me to believe the General cannot be perfectly aware of my situation, which has greatly changed within the last hour. I have just carried a crest, an advanced artillery post occupied by the enemy’s artillery supported by infantry. I am advanced a mile beyond our own lines, and in an isolated position. On my right a deep railroad cut; my left flank in the air, with no support whatever. In my front at close range is a strongly entrenched line of infantry and artillery, with projecting salients right and left such that my advance would be swept by a cross-fire, while a large fort to my left enfilades my entire advance (as I experienced in carrying this position.)

In the hollow along my front close up to the enemy’s works, appears to be bad ground, swampy, boggy, where my men would be held at great disadvantage under destructive fire.

I have got up three batteries and I am placing them on the reverse slope of this crest to enable me to hold against expected attack. To leave these guns behind me unsupported, their retreat cut off by the railroad cut, would expose them to loss in case of our repulse.

Fully aware of the responsibility I take, I beg to be assured that the order to attack with my single brigade is with the General’s full understanding. I have here a veteran brigade of six regiments, and my responsibility for these men warrants me in wishing assurance that no mistake in communicating orders compels me to sacrifice them.

From what I can see of the enemy’s lines, it is my opinion that if an assault is to be made, it should be by nothing less than the whole army.”

Chamberlain then continued his letter to the paper:

“…At one o’clock, I sounded the signal, and moved my brigade in the lines of battle in front of my guns. The moment they could do so, my batteries opened an awful fire over our heads. The enemy replied with every missile known to war at pistol range. We were also enfiladed by the heavy guns from Fort Mahone, or “Fort Damnation,” as the boys called it. It was a case where I felt it my duty to lead the charge in person, and on foot. My flag bearer had been shot dead at once. I picked up the flag—a red Maltese cross on a white field—and with my entire staff went forward. At the foot of the slope between us and the rebel works we struck soft, spongy ground, where I saw that my men would be caught. Accordingly, I faced towards them and ordered an oblique to the left. As no mortal voice could be heard in such an uproar of fire, I was waving my sabre and flag in the direction I wished my men to take, when a Minié ball of the ten thousand that were darkening the air, struck me as I was half facing to give this command. The ball entered in front of the right hip joint, passing clear through my body and coming out behind the left hip joint.”

In October 1903, shortly after a second visit to Petersburg, Chamberlain presented a paper before the Commandery of the State of Maine, Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States, titled “Reminiscences of Petersburg and Appomattox.” In it, he recounted the “impressions made upon me by a recent visit to Petersburg and Appomattox Court House, Virginia, the first and last battlefields of the final campaign of the Army of the Potomac and the Army of Northern Virginia.”

Chamberlain readily admitted that he had not had the opportunity to revisit the site of his near-mortal wounding in the years immediately following the battle. In fact, he viewed this lack of opportunity in a positive light. The intervening 39 years, he thought, was “time enough to cool one’s blood, so as to gather the various data for mature judgment, more reliable perhaps than confused recollections of personal experience.”

His recollections do seem reliable regarding the directions of his movements, and the substance of his conversations with other officers, but his grasp of the larger context of the fight is lacking. The 5th Corps arrived at Petersburg less than 24 hours prior to its engagement there. The morning of the 18th found Chamberlain’s brigade advancing against a newly entrenched opponent on the high ground east of the city. Within a matter of just a few hours, the stricken colonel was being evacuated from the field in shock. He was then absent from the Army of the Potomac for five months.

Chamberlain, understandably, may not have possessed an accurate grasp of precisely where he was on June 18, or of who was opposing him. Having learned, in retrospect, that Griffin’s division had initiated the construction of Fort Sedgwick, and knowing that he was in a fierce fight in the vicinity, Chamberlain may have assumed he was part of the assault that took and fortified the ground that “became famous throughout the siege as the hottest point of contact of the hostile lines.”

In his later years, Chamberlain seems to have been driven to flesh out the larger context of the fateful engagement. He may not, however, have been terribly thorough in his preparation: There is no reference to the official reports of his own army, or those of his Confederate foes; there is no mention of an extensive correspondence with fellow officers to clarify specific details; there is no evidence of his having spent time consulting historical maps that survive to this day.

During the 1903 visit, Chamberlain did go to the trouble of touring the battlefield with a local guide, consulting a lone, worn Confederate war map, collecting souvenir bullets, and exchanging reciprocal experiences with an anonymous old Confederate officer who may or may not have opposed him on the field of combat. His role, however, seems to have been more one of a spectator and casual sightseer rather than that of researcher.

With the benefit of the supplemental information acquired on the second visit, Chamberlain composed his speech for the enlightenment and entertainment of comrades and admirers at the MOLLUS assembly. Given the purpose of the manuscript, it is not necessarily the most reliable of historical primary source documents. In “Reminiscences,” he speaks of his proximity to the Jerusalem Plank Road. He tells of his brigade having taken and fortified ground that afterwards became strongly entrenched under the name of “Fort Sedgwick.” He mentions having confronted the infantry of Maj. Gen. Joseph B. Kershaw’s Mississippians, Georgians, and South Carolinians, as well as Alabama troops who had replaced Maj. Gen. Bushrod Johnson’s Division in the trenches early the previous evening. (Review of the historical record will show that Kershaw relieved Johnson on the evening of June 18, not June 17.) Each of these points becomes highly debatable as one carefully considers the historical record.

The details of Chamberlain’s own account of his actions on June 18 regarding terrain, direction and distance of movements, landmarks, artillery placements, etc., conflict with his interpretation. Abundant external contemporaneous testimony from multiple other sources also seems to render untenable the scenario of an attack by Chamberlain’s brigade on Rives’ Salient from the south, along the Jerusalem Plank Road.

The evidence strongly suggests that Chamberlain’s own false premise conceived the myth that has come down to us—a myth perpetuated through faithful repetition by a long line of biographers over many decades.

Author Dennis A. Rasbach, whose interest in the Petersburg Campaign was sparked by the service of an ancestor in the 21st Pennsylvania Cavalry, exhaustively lays out the case for the location of Chamberlain’s Petersburg attack in his book, Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain and the Petersburg Campaign: His Supposed Charge from Fort Hell, His Near-Mortal Wound, and a Civil War Myth Reconsidered, from which this article is adapted. Rasbach, a surgeon, resides in Michigan.