A new book on the infamous Nazi doctor’s life shows how ordinary people can be capable of extraordinary cruelty.

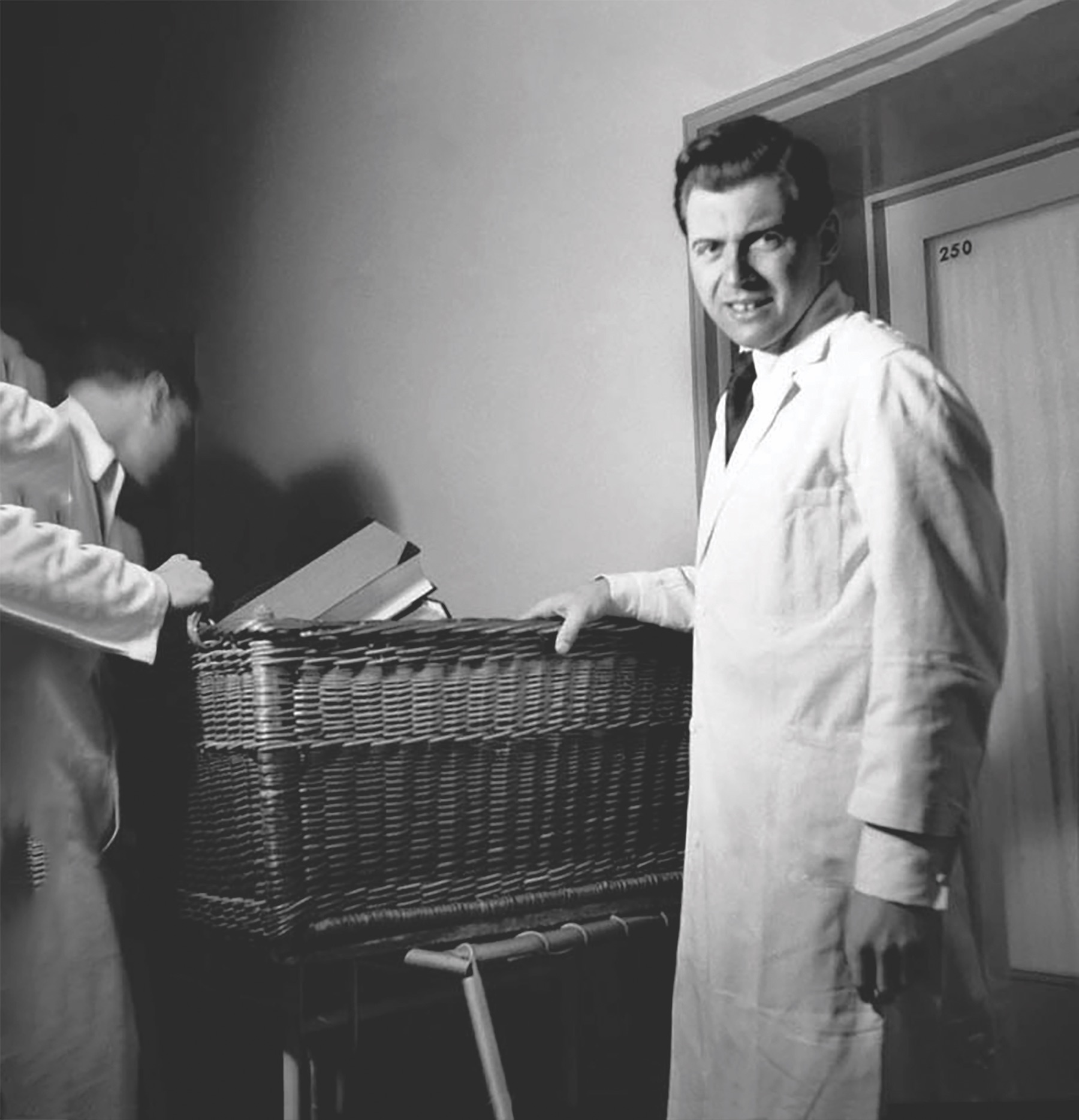

Mengele: Unmasking the “Angel of Death”

By David G. Marwell. 432 pp.

W.W. Norton & Company, 2020. $30.

In late 1940, just three years before assuming the role of Auschwitz’s “Angel of Death,” Josef Mengele was a young German medical officer on his first combat assignment with the 5th Waffen SS “Viking” Division. Mengele received the Iron Cross for helping wounded soldiers while under fire; one of his superiors recommended promotion, describing the young man as a “mature, upright, and absolutely reliable person who has the full confidence of his superiors and subordinates.”

This early glimpse of the notorious figure as a promising physician is just one surprising anecdote to emerge from historian David Marwell’s Mengele: Unmasking the “Angel of Death.” Perhaps even more surprising is the book’s extensive research showing that Mengele’s skewed scientific ideas and practices were actually typical of the era’s medical research community in Germany.

Marwell began writing this book in 2016 using recently declassified CIA files, a secret Mossad dossier, and a vast trove of the Nazi doctor’s private papers. He uses them to trace the making of Mengele, beginning with his childhood as the eldest son of a wealthy family in Bavaria. Despite a start as a lackluster student, Mengele found inspiration in medicine and anthropology and rose steadily as a university graduate scholar. But in May 1943, Mengele’s fate changed forever when he reported for duty at the Nazi death camp of Auschwitz-Birkenau, fresh from a stint at an eminent medical research institute in Berlin.

With an astonishing number of documented examples, Marwell explains how Mengele would go on to establish a robust, scientifically credible research institute at Auschwitz according to “established” (albeit pseudoscientific) concepts of racial hygiene. Were its objectives dubious? Not as described by Marwell, who points out that the goals of eugenics were regarded as acceptable around the world at the time. Were the circumstances of its collection of data—grisly forced experiments replete with amputations, blood transfusions, and deliberate infections—horrendously immoral? Absolutely.

Mengele’s reputation as the Angel of Death grew from his work on the Auschwitz railroad platform where prisoners arrived. He was one of several camp doctors who met trains and sent the very young, frail, and elderly in one direction to their deaths in gas chambers and healthy prisoners in the other direction to worker barracks. But his control over which prisoners would be forced to undergo experimental procedures for his own research—particularly twin children, prized for use in the study of genetics—cemented his reputation as a demon. A knee-jerk reaction to these atrocities is natural, but there is more to consider regarding Mengele’s motivations, Marwell writes. “The notion of Mengele as unhinged, driven by demons, and indulging grotesque and sadistic impulses should be replaced by something perhaps even more unsettling,” he explains. “Mengele was, in fact, in the scientific vanguard, enjoying the confidence and mentorship of the leaders in his field.”

After World War II, Mengele evaded capture despite sightings in Germany and across South America. Marwell himself enters the story in 1985 as a Justice Department special investigator tasked with using history as a forensic tool to revive the lapsed investigation into Mengele’s final years. As far as the public knew, Mengele’s 40-year escape from history ended June 21, 1985, in São Paulo, Brazil, when teams of prosecutors and scientists identified a set of exhumed bones as belonging to the Nazi fugitive. But lingering doubts about this conclusion led Marwell and a team of international investigators to look for additional proof that the Brazilian bones were authentic.

As the book progresses, the team’s quest evolves into a labyrinthine investigation involving an FBI laboratory at the cutting edge of DNA forensic research; lie detector negotiations between German prosecutors and two Hungarian emigres who had shielded Mengele in Brazil; and a murder mystery-esque subplot in which Mengele’s middle-aged son, Rolf, is duped into surrendering a DNA sample—confirming without question that the exhumed bones in Brazil belonged to his father.

At a book signing for Mengele: Unmasking the “Angel of Death” earlier this year, an elderly attendee, her face creased in pain, decried Marwell’s decision to trace Mengele’s life in a way that suggests he was in fact an ordinary human being. Marwell nodded and listened. His book, however, draws a hauntingly pointed conclusion: “It is easier to dismiss an individual monster than to recognize the monstrous that can emerge from otherwise respected and enshrined institutions.”

As this exceptional work clarifies, Josef Mengele was an ordinary person capable of extraordinary cruelty—and zealously mindful of his duty to a vicious regime. ✯ —John Martin is a former ABC News national correspondent.

Thank you for visiting historynet.com. If you buy something through our site, we might earn a commission.

This article was published in the August 2020 issue of World War II.