In Loudoun County, Virginia, an old brick gristmill that still straddles a millrace along the Little River Turnpike served as the backdrop for one of John Singleton Mosby’s most breathtaking exploits in March 1863. Even if Civil War students and buffs don’t know much about the mill and its history, they most certainly know a little about Aldie and its significance in the annals of the war. After all, there are countless references to Aldie in the Official Records—the 128-volume compendium of the Union and Confederate armies’ after-action reports, published by the federal government in the late 19th century—and in other primary sources, since officers on both sides often took note of the village as their troops passed through it during campaign marches or while on patrol.

The small town also gained fame for the events of June 17, 1863, when Confederate and Union cavalry clashed early in the Gettysburg Campaign. The Confederates that day, under the command of Colonel Thomas T. Munford, kept up a spirited defense against repeated assaults by Union infantry and horsemen until dusk, when they were ordered to withdraw from the field. It is said that a soon-to-be-famous Yankee cavalry captain named George Armstrong Custer, who fought at Aldie that day, got dunked in Little River while trying to water his horse not far from Aldie Mill.

But Mosby, the daring Confederate partisan warrior, is the man most often associated with Aldie. His name is in fact legendary in northwestern Virginia. During the war, the raids his partisans conducted against Union patrols, supply trains and sometimes even Federal headquarters led locals to nickname the region “Mosby’s Confederacy,” a sobriquet that today is echoed in the designation of much of Prince William and Loudoun counties as the “Mosby Heritage Area.”

For many residents of that region during the Civil War, including those who supported the Union and those who swore loyalty to the Confederacy, the activities of Mosby’s band of marauders revealed in stark and dramatic ways how the war was also an internecine conflict for neighbors who became victims or who chose different sides during the conflagration between North and South. For much of the lengthy conflict, residents of Loudoun County found themselves inadvertently caught in the grip of a destructive tug of war, as opposing armies tramped over their roads, camped in their fields, and fought battles and skirmishes across the lush landscape surrounding small farms and sprawling plantations.

Located in the northern Piedmont, with the Potomac River as its northern border and Prince William County (where the First and Second Battles of Manassas were fought) to the south, Loudoun County was strategically important because of its many primary highways. But the residents were divided in their allegiances. Many supported secession and favored the Confederate cause. Others, including the largely Quaker community of Waterford and a good number of German-Americans who had settled elsewhere in the county, held strong Unionist sentiments.

Both Confederate and Union sympathizers discovered that war could come crashing down on them at any moment, and that their farms could be repeatedly looted without regard to loyalties. Loudoun County got its first real taste of war on October 21, 1861, when the Battle of Ball’s Bluff—a Rebel victory—was fought just outside the county seat of Leesburg. Just six months later, in March 1862, Union forces successfully occupied the entire county.

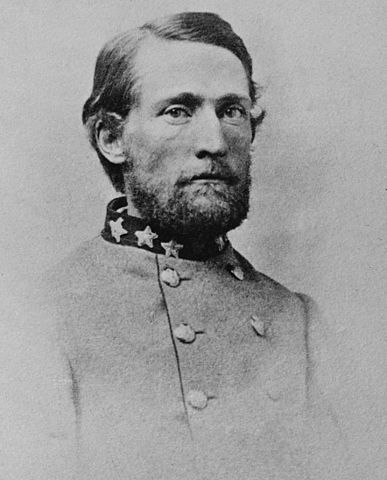

Enter John S. Mosby. The dashing Confederate cavalryman was not a native of Loudoun County and had shown no interest in the military prior to the war’s outbreak. But his early history shows an interesting mix of characteristics. Born outside of Richmond, Va., in 1833, he later attended the University of Virginia, where his violent streak—despite his diminutive stature (5-feet-7) and size (128 pounds)—landed him in real trouble. In a dispute with a town bully, Mosby shot and seriously wounded the young man. Found guilty of “malicious shooting,” he had served seven months of a one-year jail sentence when Virginia’s governor, Joseph Johnson, pardoned him just two weeks before Mosby’s 20th birthday.

That unfortunate episode sparked Mosby’s interest in the law. While incarcerated he studied law books, and continued his apprenticeship after his release, passing the bar several months later and opening his own practice in Howardsville, in Albermarle County. In 1857 he married Pauline Clarke, the daughter of a congressman and diplomat from Kentucky.

Mosby and his bride relocated to Bristol, Va., where he was practicing law when the Civil War broke out. He served with distinction in the Virginia cavalry under J.E.B. Stuart until January 1863, when he received permission to organize a unit of partisan rangers, which soon enough was mustered into General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia as the 43rd Battalion of Virginia Cavalry.

Mosby and his men engaged in guerrilla warfare, attacking Union patrols and supply trains throughout the northern Piedmont, including Federally occupied Loudoun County. For the rest of the conflict, Mosby’s Rangers would disrupt Union communications, keep Federal patrols occupied in fruitless chases, and frustrate Union commanders with his bold tactics, his wild raids and his amazing ability to avoid capture. When his raids ended, Mosby would disband his Rangers and they would return to their homes or to shelter given by relatives and friends.

The support he and his men received from Confederate sympathizers put all civilians, including Loudoun County residents, at risk, since Union officers suspected that local men were farmers by day and raiders by night. The bluecoats often tried to extricate intelligence by force from the citizenry. The climate of terror grew worse as the war continued. If Mosby’s adventures increased morale among his Rangers and civilian supporters, it also created a culture of suspicion throughout Mosby’s Confederacy. His supporters were seen more and more by Federal officers and troops as accomplices, co-conspirators and insurgents. Meanwhile, Mosby continued to carry out his plans and avoid his Yankee pursuers. As his exploits multiplied and his fame spread, he earned the romantic moniker “The Gray Ghost.”

Aldie Mill, the site of one of Mosby’s more memorable triumphs, was constructed in 1807—the brainchild of Charles Fenton Mercer, a prominent member of the Federalist Party from Loudoun County and an entrepreneur of considerable talent. At Aldie, named after Mercer’s ancestral estate in Scotland, he established a small but important industrial center, consisting of a merchant mill, a country mill, sawmill, distillery and blacksmith’s forge— all clustered in close proximity to the most prominent building, the four-story brick mill that still stands in Aldie.

On the morning of March 2, 1863, Captain John Moore, who had bought Aldie Mill from Mercer in 1835, had no hint that the war was about to arrive on his doorstep. The day had begun like any other for Moore and his workers, who were busy storing flour in the huge wooden bins on the mill’s second floor. Moore kept the dual wooden water wheels turning as the mill’s stones worked to grind the grain. Outside a Union cavalry patrol soon appeared, a frequent occurrence in recent weeks. This wouldn’t be last time that Union horsemen would ride the Little River Turnpike past the mill en route to Middleburg, five miles to the west.

Today the blue-coated soldiers belonged to the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry, under the command of Major Joseph Gilmore, which along with the 5th New York Cavalry was on an expedition to Middleburg with orders to capture the Gray Ghost. By raiding Yankee wagon trains and disrupting Northern patrols, Mosby was generally making life miserable for Union troops from Fairfax all the way to Front Royal. Gilmore hoped to find Mosby in Middleburg, since rumors had it that his headquarters were located somewhere in the town.

Mosby, who in fact had no real headquarters site, was recognized as a natural-born leader. His piercing blue eyes revealed steely determination. Whenever he spoke, one of his men remembered, his eyes “flashed the punctuations of his sentence.” When he was angry, his glare tended to chill everyone around him. Often ill-tempered and stubborn, he was notoriously restless. One acquaintance recalled that he could barely sit still for 10 minutes. Yet he was a superb horseman who could spend hours in the saddle. He also had a rich sense of humor, and around the campfire would laugh boisterously at his men’s jokes and stories. Beneath his changeable exterior, however, lay a keen intellect and the mind of a planner and schemer.

Mosby was born to fight. He improvised on the tactics of traditional warfare by striking boldly and then disappearing into the fog-covered plains and hills of Loudoun and Fauquier counties.

When Gilmore and his Union troopers rode into Middleburg that morning, they found no sign of the Gray Ghost, but they quickly captured a few of his Rangers, some unruly civilians and several barrels of whiskey, which they promptly consumed. Now reeling in the saddle, the Yankees retreated from Middleburg and passed once again through Aldie, where Moore continued with his work inside the mill. Gilmore, apparently feeling uneasy and definitely feeling his liquor, decided to leave a regiment of Vermont cavalry at the mill, just in case Mosby and his men should materialize somewhere along the Little River Turnpike. Fifty men of the 1st Vermont Cavalry, under the command of Captain F.T. Huntoon, dismounted and lounged around the mill yard, watering and resting their horses, as so many cavalry patrols had done before when they passed through.

Meanwhile Mosby and his men were gathering at Rector’s Crossroads (modern-day Atoka). When Mosby had collected 17 of his Rangers, they rode off to Middleburg, where the citizens informed them of the Yankee incursion that morning, and then headed farther east, toward Aldie.

As Mosby entered the tiny village from the west, with his Rangers strung out behind him along the dusty turnpike, he could see from a hilltop a few dawdling Yankee cavalrymen in the roadway, not paying much attention to the approach to the village. Mosby quickly spied an advantage and decided to take it. He called out “Charge!” to his Rangers behind him, spurred his horse and galloped off in a blur of dust toward the surprised Union troopers.

The Rangers riding behind him were just as astonished by his order as the Yankees would soon be, but when the partisans finally realized what Mosby had said—and that their commander was now several horse-lengths ahead of them, rushing into a bewildered cluster of Yankees—the Rangers took off after him.

When the cavalrymen in the road looked up and saw the notorious Gray Ghost pounding down the turnpike in their direction, they quickly scattered. In the mill yard, the rest of the Vermont horsemen—also caught off guard—desperately rushed to their horses and swung themselves into their saddles, hoping to get across the stone bridge that crossed the nearby Little River as quickly as possible. Other troopers, perhaps seeing their lives pass before their eyes, simply dashed pell-mell inside the mill, where Moore couldn’t have been happy to see them.

Mosby continued to gallop down the pike toward the stone bridge but soon discovered that he was now riding a runaway horse. As he later wrote:

Just as we were ascending to the top of a hill on the outskirts of the village, two [Federal] cavalrymen suddenly met us. We captured them and sent them to the rear, supposing they were videttes of Gilmer’s [sic] command. Orders were sent to the men behind to hurry up. Just then I saw two cavalrymen in blue on the pike. No others were visible, so with my squad I started at a gallop to capture them. But when we got halfway down the hill we discovered a considerable body—it turned out to be a squadron of cavalry that had dismounted. Their horses were hitched to a fence, and they were feeding at a mill. I tried to stop, but my horse…ran at full speed, entirely beyond my control. But the [Union] cavalry at the mill were taken absolutely by surprise by the irruption; their videttes had not fired, and they were as much shocked as if we had dropped from the sky. They never waited to see how many of us there were. A panic seized them. Without stopping to bridle their horses or to fight on foot, they scattered in all directions. Some hid in the mill; others ran to Bull Run Mountain near by. Just as we got to the mill, I saw another body of cavalry ahead of me on the pike, gazing in bewildered astonishment at the sight. To save myself, I jumped off my horse and my men stopped, but fortunately the mounted party in front of me saw those I had left behind coming to my relief, so they wheeled and started full speed down the pike.

Meanwhile, Mosby’s men were chasing down the Vermonters who had remained at the mill. Some of the Union cavalrymen attempted to hide in the flour bins on the second floor; others jumped into the grain hoppers and came close, as Mosby later wrote, to “being ground up into flour.” His men, he reported, had “a great deal of fun pulling the Vermont boys out of flour bins.” When the Rangers got them out of the bins, said Mosby, “there was nothing blue about them.” The first Yankee prisoner his men brought out of the mill “was so caked in flour” that Mosby thought his Rangers had inadvertently captured Captain Moore, the miller.

Now horseless, Mosby started walking toward the mill, and was met near the bridge by a particularly courageous Vermont officer, a Captain Worthington. The Yankee was in turn confronted by one of Mosby’s men, a Marylander named Tom Turner, who fired at Worthington. The bullet wounded the captain’s horse, pinning the Yankee to the ground. Worthington managed to return fire, severely wounding Turner, who later claimed he had been shot after his opponent had surrendered. A contingent of Rangers called for the Yankee’s execution, but Worthington denied he had committed such a breach of military protocol—that he had fired in a fair fight.

Mosby sided with Worthington. He instructed his men to remove the Vermonter from under his horse rather than take him into custody. Too badly injured to return to his lines, however, Worthington remained with a family in Aldie to be cared for and reclaimed by the next Union patrol passing through the village.

All in all, Mosby and his men captured 20 prisoners that day, including Captain Huntoon, the 1st Vermont’s commanding officer, and 23 horses. After Mosby sent his men off to Middleburg with their prisoners, he lingered for a while at the mill. As he rested, three more Vermonters emerged from the flour bins and were captured. No more than half a dozen shots had been fired during the whole episode in front of Aldie Mill, Mosby later claimed. Only two of his men were wounded: Turner and an unnamed raider.

As the Rangers returned to Middleburg with their prisoners, the local citizens at first saw only a column of blue-coated men coming down the road and feared that meant Mosby and his men had been captured. A Ranger, however, quickly galloped out of the pack and dashed forward to trumpet the Confederate victory, prompting a loud cheer from the residents. By that time they could see that the bluecoats were prisoners being escorted by Mosby’s proud Rangers. “There was rejoicing in Middleburg that night,” Mosby wrote years later. “At night, with song and dance, we celebrated the events, and forgot the dangers of the day.” Mosby also made sure to note that Captain Moore, the Aldie miller, was relieved by the Rangers’ intervention. It turned out they had arrived just in time to save his corn and flour from being purloined by the Vermont troopers.

With modesty, Mosby wrote in his memoirs: “In this affair I got the reputation of a hero; really I never claimed it, but gave my horse all the credit.” As for the horse, Mosby never recovered it—and given that particular mount’s behavior in combat, he probably figured that was for the best.

But what Mosby seemed to be saying, in his own self-effacing way, was that his courage that day in front of Aldie Mill had not been all that commendable, and that the bravery he was credited with as he charged down the roadway toward the Yankee cavalrymen was to a certain extent accidental and completely reflexive—automatic, instinctive, involuntary courage.

There would be other occasions when Mosby and his men again found themselves fighting near Aldie Mill. Nearly a year later, his Rangers engaged in a hot skirmish with Union cavalry along the five-mile stretch of road linking Middleburg and Aldie. On July 6, 1864, he and his men fought a more heated battle with the enemy near Mount Zion Church, less than a mile east of the mill. And on September 15, 1864, Mosby himself was badly wounded when a bullet hit the grip of his pistol during a skirmish with the 13th New York Cavalry nearby.

In April 1865, after Robert E. Lee surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox, Mosby and his Rangers refused to capitulate. Instead, they headed back in the direction of his old stomping grounds, and on April 21 Mosby disbanded his partisans in Salem, Va. (modern-day Marshall). Once the war was over, the Gray Ghost accepted defeat and became a reconciliationist. He ended up campaigning for Grant in the presidential election of 1868 and later served as his consul to Hong Kong.

Many of Mosby’s fellow Virginians could never forgive him for becoming a Republican in the postwar era, but the former Gray Ghost shrugged off their disdain and ignored the many death threats he received. In standing firm for his principles during and after the war, Mosby proved that his courage was by no means accidental, but deliberate, steady and sure.

Glenn W. LaFantasie, a frequent contributor, is the Richard Frockt Family Professor of Civil War History and Director of the Institute for Civil War Studies at Western Kentucky University, Bowling Green.

Originally published in the April 2012 issue of Civil War Times.