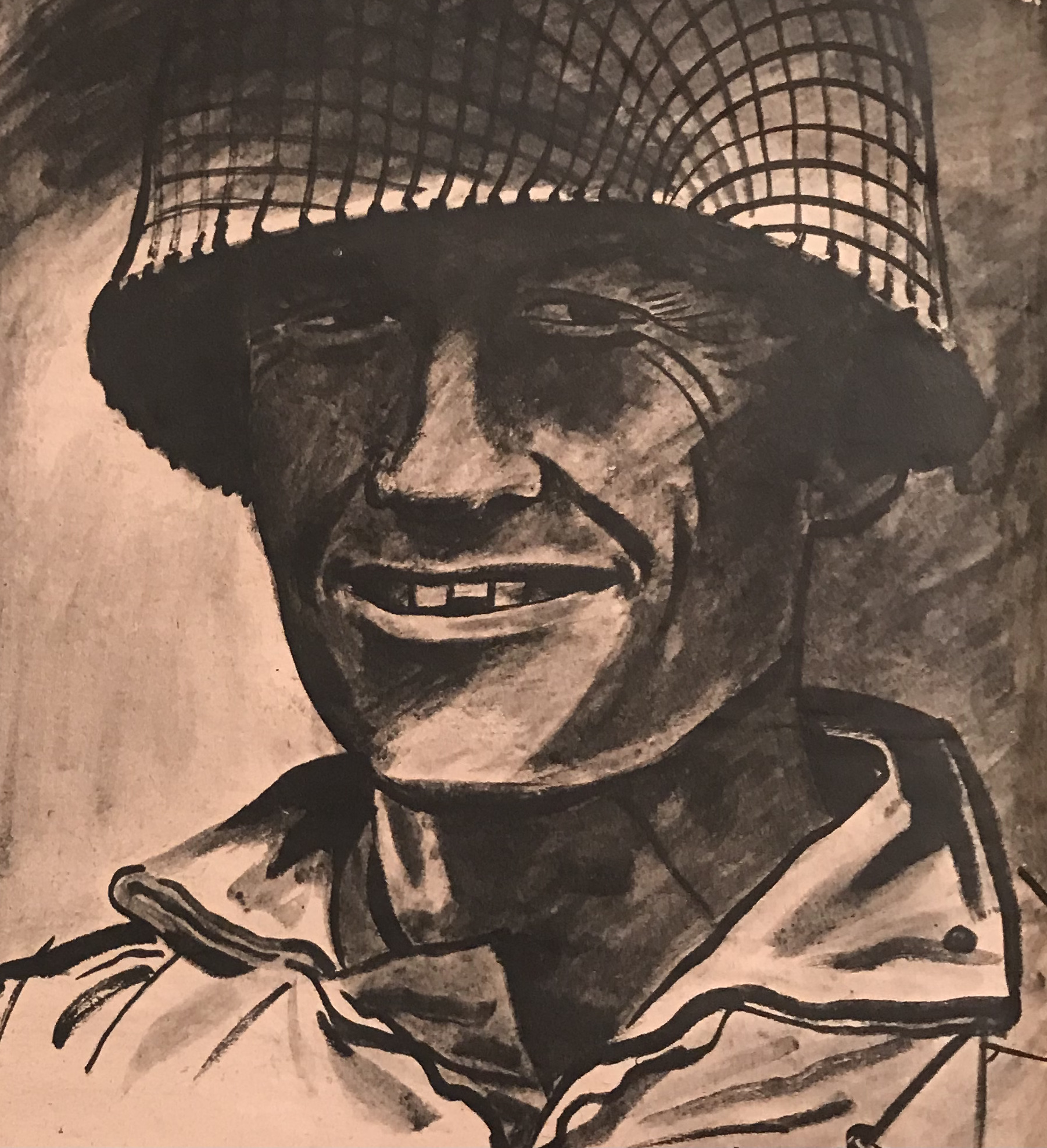

Enlisting in the Army in 1940, John Shelby, a lean 6’0, 150-pound, chip-toothed Texan, found himself in the 131st Infantry.

At America’s entry into the war, however, the hard-charging Texan and former cowboy requested a transfer to the 1st Division, 16th Infantry. He wanted a fight.

Prior to landing with the Big Red One in North Africa in 1942, the then-23-year-old had already become a sergeant four times and busted down four times in the span of a year and a half.

Despite putting little stock in rank, Shelby quickly earned the respect of his unit. He was, wrote Yank, The Army Weekly staff correspondent Sergeant Bill Davidson, “one of the fightingest, most decorated, best known and best liked men in the 1st Division.”

Shelby’s war began in the early hours of November 8, 1942, as the buck sergeant and his mortar section waded towards the shores of Oran, Algeria. The landing had gone without incident until a few hundred yards inland the men of the Big Red One were met with blistering enemy machine gun and rifle fire. Operation Torch — America’s first land invasion of World War II — was underway.

Pinned behind a stone wall in an apple orchard, Shelby and his men were trapped for the better part of the day. By nightfall an enemy mortar battery had set the men of the 16th Infantry within its sights and began to cut up Shelby’s battalion, according to Davidson.

In the darkness, Shelby furiously shot off 75 rounds — using enemy tracers to pinpoint the location of the machine gun and mortar nest. The hail of bullets from the enemy stopped as quickly as it had started.

Cited for gallantry in action, Shelby was recommended for the Silver Star, but due to a clerical error Shelby’s paperwork got mixed in with a batch of Purple Heart awards. Shelby didn’t say a word as he was presented the latter instead.

The sergeant didn’t have a scratch on him — yet.

At the Battle of Kasserine Pass — one of the first major battlefield encounters that pitted raw American troops against Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Korps — Shelby displayed immense grit despite what has long been ranked as one of the worst disasters ever suffered by the United States Army.

“In 10 days,” writes historian Stephen Budiansky, “panicked American forces were hurled back 50 miles, losing 183 tanks and nearly 7,000 men, including 300 killed and 3,000 missing.”

As the men of the 1st Division retreated and as Shelby was “dutifully scrubbing the dust out of his ears,” and patching up a “neck full of shell fragments” writes Davidson, his company commander Captain Edmund Driscoll pulled the Texan aside, asking if Shelby would like to be a second lieutenant.

Stammering out a “Yes, sir,” Shelby quickly saluted and walked off.

Although steadily rising in rank, according to Captain Jacob Margolis, Shelby’s “men respect him so much for what he’s done that they’d follow him even if he were a private.”

Shelby went on to see action in Sicily, where he was awarded the first of two Distinguished Crosses for gallantry in action with his citation reading:

In the course of a savage counterattack by some thirty enemy tanks and infantry to drive through, First Lieutenant Shelby with complete disregard for his personal safety moved to an observation post in advance of his battalion. Though subjected to intense artillery and small arms fire in his vulnerable position, he laid the fire of his mortar platoon on the enemy infantry with such devastating effect that their attack was disorganized. Though subjected to fierce tank fire, he continued to call for his own fire until the shells from his own guns were falling within one hundred and fifty yards of his position. He remained at this forward post until it was physically overrun by the enemy armor. Escaping injury, he returned to his own unit and continued the fight until the enemy withdrew with heavy losses.

The German armored counterattack almost drove the men of the 1st into the sea that day with Shelby’s platoon later credited for splintering the enemy’s maneuver. But in that moment, Shelby later recounted to Davidson, “we thought we were all done.”

After two years of continuous combat, the young Texan’s formerly thick black hair had gone gray due to the stresses of battle.

Shelby’s war was not over, however.

Landing on Omaha beach near Colleville-sur-Mer, on June 6, 1944, the men of the 1st Division, 16th Infantry faced heavy German resistance. Terrified soldiers began bunching up along the shoreline until the 16th’s commander, Colonel George A. Taylor famously declared, “Two kinds of people are staying on this beach, the dead and those who are going to die — now let’s get the hell out of here.”

Shelby did indeed get the hell out of there — perilously crossing a minefield and traversing up the ridge to do so. Three men in his unit were killed in the crossing.

On top of the ridge Shelby and his men immediately encountered German resistance. After forcing an enemy antitank crew to surrender, Shelby personally charged at a German machine gun nest a short distance away, killing the two gunners with three bullets.

Charging off to the village of Colleville to set up an observation post, Shelby and two soldiers — Corporal Peter Cavalierre and Private Joseph Parke — soon found themselves surrounded by a company of 200 Germans intent on dislodging them from a French home on the outskirts of town.

Displaying some American ingenuity, Shelby and his platoon simply switched houses, watching as the Germans brought up a tank and bazookas to fire into the now-vacant home.

Realizing their mistake, the Germans continued their onslaught, but the three men managed to hold out until the aptly named battleship Texas opened up its 14-inch guns on the enemy from offshore.

“The three men,” writes Davidson, “had disrupted the whole German plan of defense in that area and tied up hundreds of Nazis who might have been kicking around the GIs pinned down on the beach.”

From Colleville to the breakthrough at St. Lo, to the race through France, Belgium, and finally on to Germany, Shelby fought through it all.

Despite telling Davidson that after the war he was going to take the $5,000 he had “won in craps games in the Army” to “open up a cocktail bar in the Loop in Chicago” Shelby remained in the Army until receiving a medical discharge in 1959.

Awarded two Distinguished Crosses, the Silver Star, Two Bronze Stars, and the Purple Heart — the only decoration Shelby ever donned was his Combat Infantry Badge.

“Heroism is something that a guy does automatically to save his own can,” Shelby recounted. “The real heroes are the guys who do the job up front every day without getting their can into a place where it has to be saved.”